The trial and conviction of Magalie Bamu and Eric Bikubi this March for the murder of 15-year-old Kristy Bamu was one of the most horrifying criminal cases of recent years. Horrifying for the level of violence and suffering inflicted: Kristy was tortured, beaten and cut over several days before he was finally drowned in the bath. Horrifying because of the relationship between the victim and his killer – Magalie was not only Kristy’s sister, she was also supposed to be caring for her brother and their other siblings during a holiday visit from France. And horrifying because the two killers were motivated by beliefs that seem both frighteningly alien and disturbingly irrational in the broadly secular Britain of 2012: they were convinced that Kristy was a witch.

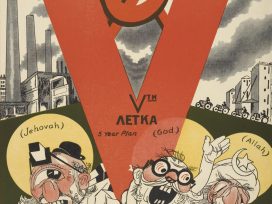

This isn’t just a case of tragic, private delusion. The belief in evil as an active, independent agent, capable of possessing an individual or being controlled by them to harm others, is a rarely acknowledged but implicitly mainstream part of Christianity. Although accusations of possession generally start with independent charismatic preachers, the Church of England has its own institutional guidelines for the provision of exorcisms – and John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York and likely successor to Rowan Williams, has told the House of Lords how he performed a ritual to free a young girl from a supernatural influence contracted at a witches’ coven. From a rationalist, secular perspective, the impulse to reject and uproot such beliefs is strong. But for those concerned directly with the safety of children, the balance between confrontation and accommodation is a more subtle one.

This isn’t just a case of tragic, private delusion. The belief in evil as an active, independent agent, capable of possessing an individual or being controlled by them to harm others, is a rarely acknowledged but implicitly mainstream part of Christianity. Although accusations of possession generally start with independent charismatic preachers, the Church of England has its own institutional guidelines for the provision of exorcisms – and John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York and likely successor to Rowan Williams, has told the House of Lords how he performed a ritual to free a young girl from a supernatural influence contracted at a witches’ coven. From a rationalist, secular perspective, the impulse to reject and uproot such beliefs is strong. But for those concerned directly with the safety of children, the balance between confrontation and accommodation is a more subtle one.

The killing of Kristy Bamu follows a number of disturbing cases involving folk beliefs about witchcraft and possession among west African immigrants in the UK, beginning with Victoria Climbié’s murder in 2000 and including the extreme and extended abuse of “Child B” revealed in 2005. But child protection experts say that these high-profile examples represent only a tiny proportion of the actual incidence of such beliefs, with many victims experiencing profound psychological abuse for which their tormentors will never be prosecuted. “We need to be very clear that belief in witchcraft is widespread among the black community,” says Justin Bahunga of the UK charity Afruca (Africans Unite Against Child Abuse).

Such beliefs aren’t necessarily a cause of harm. “There is no automatic link between belief and abuse,” says Bahunga, “but there are triggers that make belief move from being a neutral factor to causing people to harm others.” There’s some uncertainty about how exclusive this phenomenon is to West African culture. The Stobart report into witchcraft and spirit-possession-related child abuse stresses that the prominence of West African immigrants within confirmed cases may simply be a bias caused by previous work on this community. Cases have been linked to Christian and Islamic backgrounds, involving African, Asian and (in at least one instance) white British families.

However, details of child abuse involving witchcraft accusations are not systematically recorded, nor are social workers always trained to detect them, so gauging the problem is extremely difficult: a statement from Project Violet (the Met’s specialist unit dealing such with cases) describes belief-based child abuse as a hidden crime. Afruca estimates that it deals with a dozen cases a year, but many more children are tagged as “witches” or “possessed” without meeting the threshhold for intervention: I spoke to a teacher of children with profound learning disabilities who described several cases from her own practice in which parents suggested a supernatural explanation for their child’s special needs, including Somali Muslim parents who asked whether she thought their son “had the Devil in him”.

“I think the low and medium level is appearing far, far more often,” says child protection trainer Perdeep Gill, who has researched witchcraft-related abuse among African and Asian communities in London. One bar to identifying victims is that the child who is a victim of witchcraft-related abuse is often very similar to the child who is a victim of ordinary abuse. According to the Stobart report, the children involved were often living with a carer who was not their parent, often scapegoated for problems afflicting the family (for example, unemployment or immigration issues), and often singled out for being “different” – either because of a disability or a behavioural issue such as bedwetting, sleepwalking or rebelliousness. Their abusers often suffered from mental illness (in the case of Kristy Bamu, part of Bikubi’s defence was that he had brain damage).

In other words, despite the sensational nature of their cases, these children are tragically typical victims. “Usually, there’s some kind of vulnerability,” says Gill. Often that vulnerability is closely related to immigration status – not necessarily because adults are applying the brutal principles of foreign culture, but because a combination of past trauma, the struggle to adapt to a new (often hostile) home, and linguistic or knowledge barriers to accessing appropriate secular agencies means that the conditions for abuse become especially acute.

Moreover, there’s one particular risk factor that is specifically exacerbated by immigration: a broken attachment bond between a child and its carers. That doesn’t only refer to cases where a child is fostered overseas with extended family or a non-relative guardian, but also to situations where the children join the parents after an interval. In one case Gill dealt with, she says, “[The parents] were emotionally connected to these very little children who they no longer are. They look poor, and I think this was the parents not wanting to be identified with their own poverty and where they’ve come from.” Alternatively, children may adapt to their adopted country better than their carers, and subsequently behave in ways that are interpreted as evidence of a “demon of rebellion”. The strains are profound and complex.

Missing the belief background of a case can be deadly. Gill mentions the case of a toddler who had been identified as a victim of physical abuse – but without recognition of the cultural context of his injuries, no one anticipated the way in which the abuse would escalate. “The father thought the child was possessed by djinn,” she explains. “We could have prevented the child’s death if we’d known that.”

Ignorance of possession and witchcraft claims can also mean that the pervasive emotional brutality done to children is overlooked: Afruca considers the effects of accusations against children to be so severe that they should be criminalized as a form of abuse in themselves. “Once you say a child is a witch, you are saying the child is an evil person who can kill or cause misfortune. How do we rehabilitate this person who has been stigmatized in the community?” says Bahunga. The Stobart report outlines some of the forms this ostracism may take, from accused children being forced to eat apart from the rest of the family to siblings being encouraged to participate in the abuse (again, this was a feature of the Bamu case). The consequences for the victim are of course devastating, as Stobart elaborates: “Children… showed behaviour consistent with distress. They frequently appeared isolated, quiet, withdrawn and sad.”

And it’s important to remember that the victims often share the beliefs that enable their abuse. When children experience rejection from their carers or community, there is even a perverse incentive for partaking in communal faith: they can demonstrate that they belong, even if the terms of that belonging are also the terms on which they are accused. (Of course, many victims – Bamu included – are simply tortured into making a confession.) Gill describes an encounter with a group of mothers who had been charged with being witches by a pastor: “They were distressed, angry, they said they didn’t accept what he said. [But] the power of the belief system was such that they were scared that at night they were turning into bats and going off to drink blood, or their children who had also been named were doing the same. It was phenomenal.”

Religious leaders play a critical role in these cases, either by making the initial accusation or by confirming an abuser’s charge against a child. While the Laming report into Victoria Climbié’s murder understandably focused on the failures of health and social work professionals, it also raised concern about her contact with two pastors during the period of her abuse. Although one claimed to be alarmed that Victoria’s carers said she was “possessed by Satan”, he didn’t take his concerns to any child protection agency. The other interpreted her injuries not as signs of adult violence but as confirmation that she was in the grip of malign spirits – not only failing to help the child, but reinforcing the logic of her torturers and assisting the escalation of their abuse.

Laming also drew out the danger of mistaking complacency for tolerance, by highlighting the way that professed cultural sensitivity led professionals (both white and black) to interpret signs of Victoria’s abuse as “normal” for an African family. The most generous interpretation of this is that it was incompetence born of excessive delicacy where professionals feared intervention could be interpreted as racism. A more sceptical account says that it was a form of racism in its own right, whereby a fatal standard of care was deemed acceptable simply because Victoria was black. Any professional who tolerates an accusation of witchcraft or possession against a child in the name of multiculturalism is clearly failing in their child protection duties; and yet those who work directly with children at risk also recognize that open hostility to a widely held belief is not likely to further a child’s safety.

“There’s no point in saying this isn’t the case, because it’s such an embedded belief system,” says Gill. “When I’m working with families, the kind of thing I’m saying to them is, ‘Are you sure it’s God who told you this child is a witch? Has it ever occurred to you the Bible tells you there are many voices that pretend to be God?’ I try to create cognitive dissonance around the belief.” It’s a necessarily subtle approach, because, for the first- or second-generation immigrant families who make up the majority of these abuse cases, the church may be their only way of getting help – a point stressed by Bahunga. “When you arrive, you don’t know where to get information, you don’t know where to get support,” he says. “The most accessible support system or network is the church, and that’s where you become very vulnerable to rogue pastors.”

Afruca is campaigning for places of worship to be regulated: despite the position of pastors as community leaders, there are no entry criteria for setting up a church, and nothing to protect distressed families and children from the influence of unscrupulous preachers who may well have a financial stake in diagnosing possession. “You can wake up in a day and say, ‘I’ve had a vision’ or ‘I’ve had a calling’ and there’s nobody to say no,” says Bahunga. “What is missing is actually making the people who accuse children of being witches accountable.” Churches have a unique ability to influence these child abuse cases, for the worse (as in the Climbié case) but also for the better, through the relationship between an individual and their church.

Whatever the personal beliefs of those working in child protection, that means they have an obligation to work with religious leaders. So while it may be shocking that the Church of England seems to endorse these beliefs, the Church’s guidelines for dealing with spirit possession accusations are also an example of how that might be accomplished. Ministers must ensure that medical care is sought before they can consider an exorcism; the ritual must be authorized by a bishop, and ongoing pastoral care is required afterwards. When the subject of the exorcism is a child, the diocese’s safeguarding children adviser must be involved, and they are urged to refer the case to statutory authorities if necessary.

The element of discretion here is problematic, given that accusations of possession can be considered abusive in their own right; but it is also arguably essential to maintaining the trust that brings a concerned parent to seek help from the Church in the first place. For those who believe in spirit possession and witches as material truths, the world is conceived as a battle between the forces of good and evil with children caught in the middle. To protect children, it’s not enough to launch a second war between belief and rationalism: faith is the cause of this abuse, but it may also be the only way of reaching and helping many of the victims.

Find out more at afruca.org

This isn’t just a case of tragic, private delusion. The belief in evil as an active, independent agent, capable of possessing an individual or being controlled by them to harm others, is a rarely acknowledged but implicitly mainstream part of Christianity. Although accusations of possession generally start with independent charismatic preachers, the Church of England has its own institutional guidelines for the provision of exorcisms – and John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York and likely successor to Rowan Williams, has told the House of Lords how he performed a ritual to free a young girl from a supernatural influence contracted at a witches’ coven. From a rationalist, secular perspective, the impulse to reject and uproot such beliefs is strong. But for those concerned directly with the safety of children, the balance between confrontation and accommodation is a more subtle one.

This isn’t just a case of tragic, private delusion. The belief in evil as an active, independent agent, capable of possessing an individual or being controlled by them to harm others, is a rarely acknowledged but implicitly mainstream part of Christianity. Although accusations of possession generally start with independent charismatic preachers, the Church of England has its own institutional guidelines for the provision of exorcisms – and John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York and likely successor to Rowan Williams, has told the House of Lords how he performed a ritual to free a young girl from a supernatural influence contracted at a witches’ coven. From a rationalist, secular perspective, the impulse to reject and uproot such beliefs is strong. But for those concerned directly with the safety of children, the balance between confrontation and accommodation is a more subtle one.