German journal ‘Osteuropa’ acknowledges the lasting struggles of Babi Yar. An overlooked testimony reflects previously suppressed knowledge of the 1941 massacre. Also: the site’s troubled history of memorial; and tackling Soviet antisemitism and censorship.

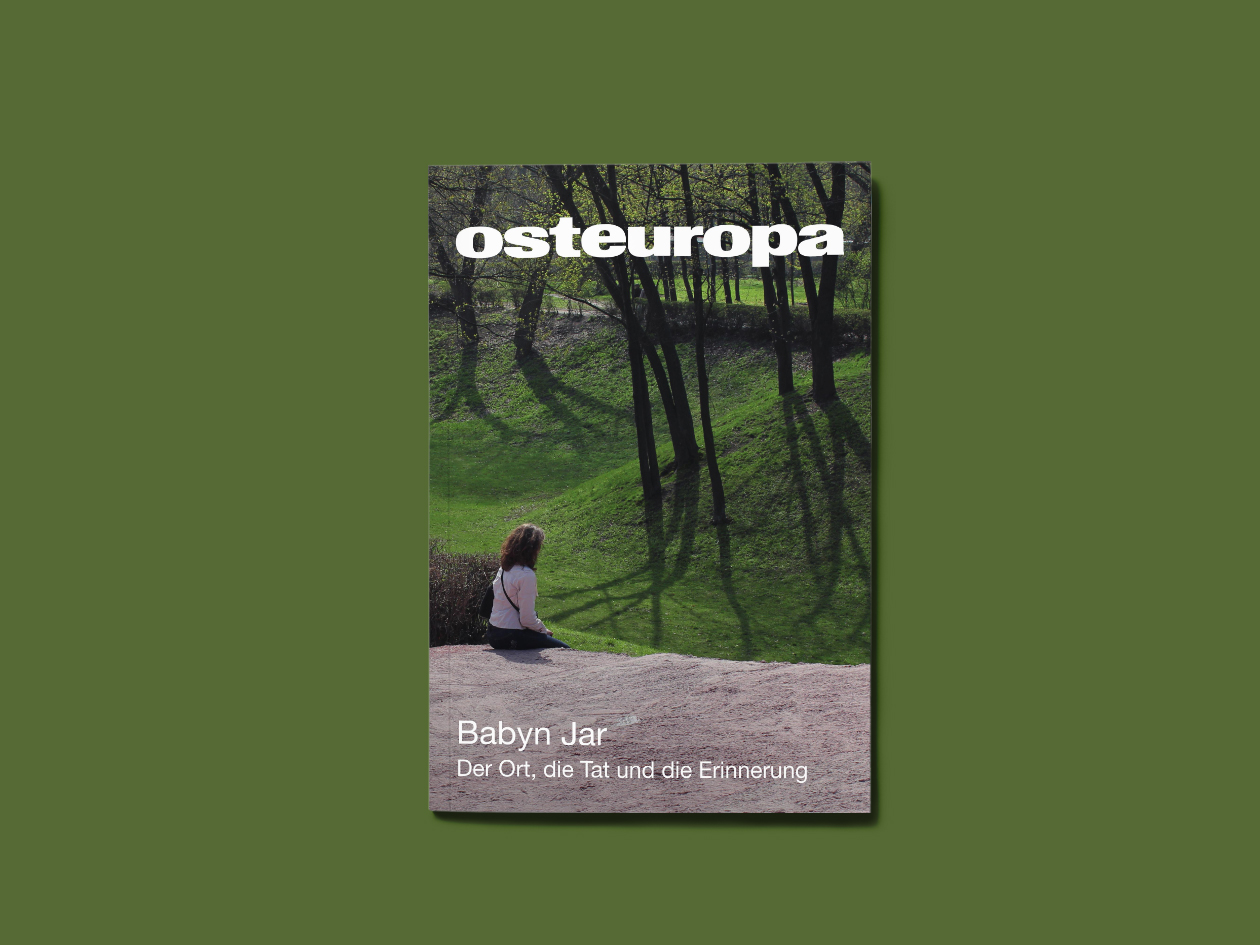

Osteuropa devotes its first edition this year to the Babi Yar massacre, marking eighty years since Nazi forces shot dead tens of thousands of Jews in a ravine on the outskirts of Kiev.

Parables of social housing

NAQD 38-39/2020

Revealing testimonies

Osteuropa 1-2/2021

Escaping bounds

The Dutch Review of Books 3/2021

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

Excerpts of Dina Proničeva’s statement, given at the 1960s Callsen Trial, are published here. One of the very few survivors of the massacre, the Ukrainian woman testified despite initial anxiety about visiting the homeland of her oppressors and the reluctance of Soviet authorities to allow her to travel. Her eyewitness account, which describes the run-up to the massacre, the events of the day itself and her astonishing escape from the mass grave, is largely unknown.Had Proničeva not lived in a dictatorship determined to conceal how Nazis deliberately targeted Jews, Karel Berkhoff suggests that her survivor’s story would have been internationally recognized. Instead, her testimony suffered the same suppression as the Babi Yar massacre itself.

Painstaking memorial

Vladyslav Hrynevyč describes the Babi Yar site as a Ukrainian ‘lieu de mémoire’ with a symbolic role at the heart of conflict over the remembrance of Ukraine’s past. In the early postwar period, the Stalinist government downplayed the Jewish identity of most victims. Despite early calls from the Jewish community for a memorial at Babi Yar, the site was used as a sludge waste outflow area from a clay pit in the 1950s.

A memorial demonstration in 1966 helped to crystallize the site as a nexus of dissident opposition consolidating Jewish and Ukrainian nationalist activist efforts. The site’s symbolic importance grew over subsequent decades: in the 1970s and 1980s, a visit to Babi Yar became a rite of passage for many local Jews, an expression of both civil disobedience and the preservation of history.

Despite some liberalization under Gorbachev, it was not until Ukrainian independence in 1991 that attempts to memorialize the site stopped being treated with suspicion by local authorities; Jews were finally acknowledged as Babi Yar victims.

Nevertheless, official attitudes towards the site continue to shift with the vicissitudes of Ukrainian politics depending on preferred historical narratives and relationships towards Russia and the EU. The current conflict revolves around three proposed designs for a memorial complex, each supported and financed by opposing state and/or private stakeholders.

Literary escape

Sonja Margolina writes about Anatoly Kuznetsov, author of the documentary novel Babi Yar. As a twelve-year-old living nearby, he witnessed the mass shootings and kept a diary of the German occupation. Twenty years later, pursued by nightmares and shocked by the lack of official recognition for Jewish victims, he used his and other eyewitness accounts to write his book.

A heavily censored version was published in the USSR. Furious at the injustice, Kuznetsov managed to smuggle the original manuscript to London when on a research trip for a novel about Lenin; he immediately claimed political asylum. The book has since been republished with the censored sections restored and set off in italics: a graphic representation of the limits of expression in the USSR.

This article is part of the 11/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 7 July 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Under the aegis of the Council of Europe, a ‘core’ group of countries have been moving forward with plans for a tribunal capable of prosecuting the Russian leadership for the crime of international aggression. The US administration’s switch of allegiance now puts these plans at risk, writes Gwara Media.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, and not the human chain across the Baltics, is emblematic of 1989. But what if this show of unity had become iconic of communism’s disintegration? Could acknowledging Eastern Europe’s liberation positively reframe what Russia otherwise perceives as loss since the Soviet Union’s demise?