80 years after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, European memory politics is once again drawn up to the surface. These topical reads look into the populist treatment of WWII responsibility, and the consequences of a fragmented remembrance.

Explore these reads from Eurozine’s vast archive!

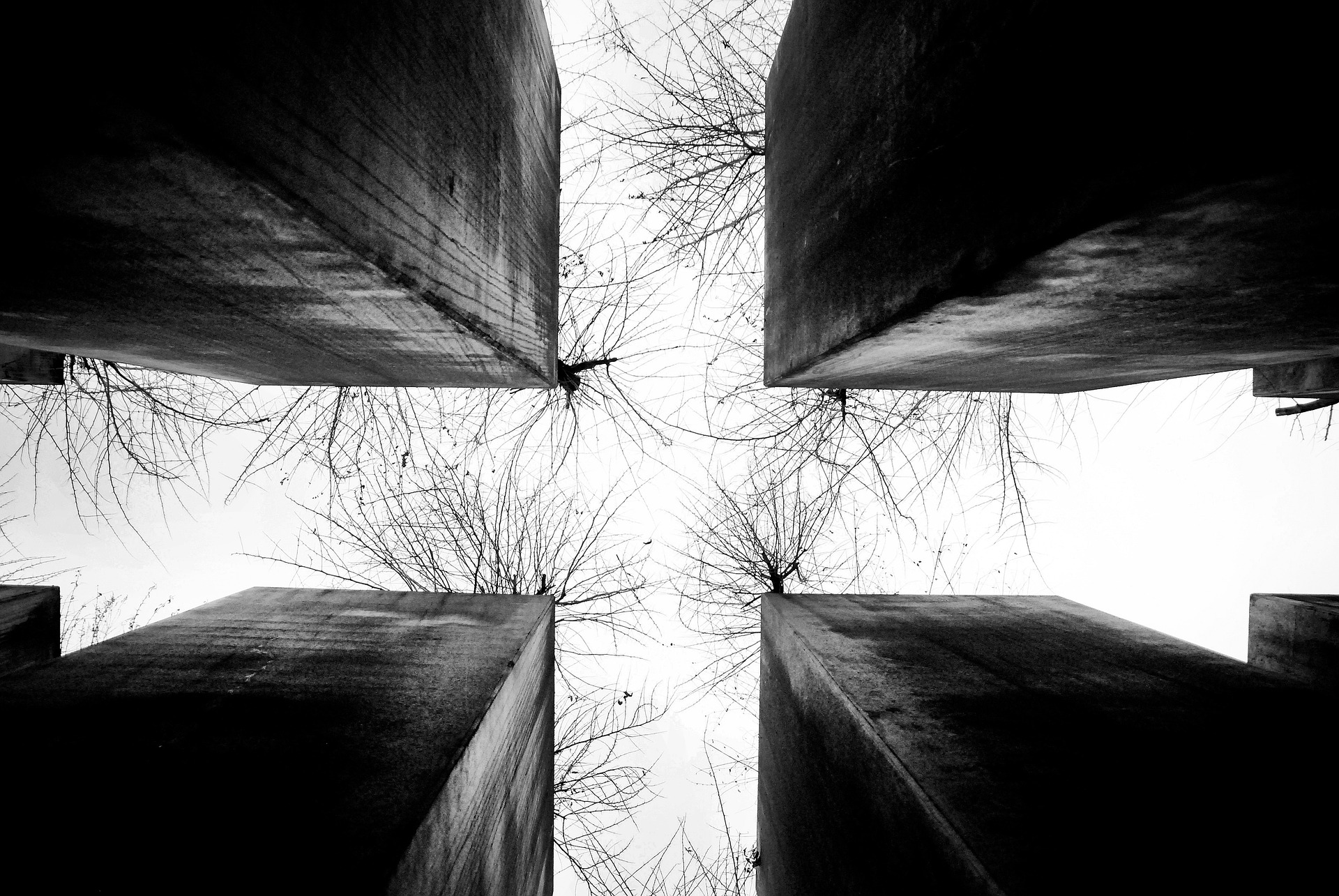

Landscape at the Jüdisches Museum Berlin. By Chiaravi on Pixabay.

During the Pesach of 1943 German troops entered the Warsaw ghetto gates to continue the extermination of the remaining 35,000-50,000 inhabitants. The resistance put up by the Jewish fighters has become a celebrated political milestone.

This week marks the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Lidia Zessin-Jurek writes on the commemorations, which brought the Polish, Israeli and German heads of state together there for the first time. Although it may seem like a moment of unity at first glance, this event reflects a deliberate fragmentation of memory, and the searing conflict that threatens behind the scenes.

André Liebich writes on the Polish ‘Holocaust law’, the government’s attempt to erase the responsibility of Polish Christians in the Holocaust. This act of historic detachment is now a part of European political culture. In post-war Europe, it has been a widespread method to regain international trust and respect. But the Polish ‘Holocaust law’ proved to be too apparent to bypass attention of Israel and the US.

The attempt to politically wipe off the historical dirt does not only cause international conflict. The law seems to gradually alter individual perceptions as well, since it attempts to victimize Poland as a nation. It rhetorically equates Polish and Jewish victimhood and fuels the fragmentation of the Holocaust remembrance.

Distorting history to build a narrative of ‘restoring national glory’ is not a new invention. Still, the methods are gaining more steam. Viktor Orbán’s regime does a lot to deny Hungarian involvement or responsibility for WWII, let alone the Holocaust, projecting Hungary as a healer of imperial wounds. In Poland, the aim is to criminalize anything that says the opposite to Polish innocence.

Irena Maryniak writes on the culture wars of the past, and how eastern European populists abuse the historical sense of societies that’ve been torn up, and rebuilt through decades of war, oppression and trauma.

Remembering to forget

Memory politics in Poland and Hungary

Who’s trauma is worthy of remembrance? It took 71 years for a Europe to acknowledge the genocide of Roma in WWII – a reflection of the enduring political and social hostility against the Roma minority. This resentment has been politically upheld through six centuries of European history, and still echoes still within the walls of the European Parliament. Violence against Roma has remained a part of European normality even after the abolishment of Romani slavery in 1856.

The Romani of Europe have been left to their own means to heal the wounds of the Holocaust.

‘How can a relentlessly persecuted community heal without the clear condemnation of the violence they endure, while also being barred by political leaders?’ asks the writer Marko Pecak.

Roma communities never got a break

Roma Holocaust Memorial Day 2020

Ferenc Laczó’s Holocaust Memorial Lecture breaks down how the Europeanization of Holocaust history has a far way to go. In light of the Polish ‘Holocaust law’ Laczó’s thorough review of the difficulties in holding nations accountable, when the history of Jewish oppression is tightly intertwined with Europe as a whole.

‘concurrent discourses on shared European responsibilities have not yet established themselves as mainstream, demonstrating the continuing limits to the Europeanization of Holocaust remembrance in our age.’ Laczó writes.

The Europeanization of Holocaust remembrance

How far has it gone, and how far can it go?

Free access to history itself provides the democratic individual with a weapon against tyranny. Timothy Snyder writes on the power of history and the Russian organization Memorial, an NGO founded when Gorbachev decriminalized critical examination of Soviet history. Since the publishing of this article, in 2022, Memorial received the Nobel Peace Prize for their work. The organization has now been forced to close down in Russia, but the work has continued abroad. Without Memorial’s research, international accounts of the GULAG would have been impossible.

‘Democracy means that people rule, but to do so, they need tools to see through the lies told by the powerful. Reflection requires facts, and getting at them is harder than it seems.’ writes Snyder.

A personal story of art and memory: Zsuzsi Flohr writes about the mysterious story of her grandpa’s backpack that has led her down a path of discovering her family’s survival story: through labour camp, and beyond.

Flohr weaves together the fragments of her family’s postmemory, as a third-generation Hungarian holocaust survivor. Examining the nuances in the stories she’s been told and the contradicting narratives within her own family, creates a reflection on how memory is altered through generations.

‘My own imagined world is populated by ghosts of past stories, objects that have disappeared, photographs never seen, letters never read, abandoned spaces of intimacy or horror, homes without addresses, missing information, and the shadows of nameless people who were unable to say goodbye.’

Published 20 April 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

On the border between Poland and Belarus, the Forest has become the subject of a humanitarian crisis. An artist’s report, based on meetings with activists and refugees, charts this contested space. Poetry honours those lost in transit.

Neganthropology

Czas Kultury 2/2024

The politics and psychology of locality: on reviving local communities as high-tech expands and diversifies; forming networks against entropy; the Tortoise Strategy for caring; and rewriting life scripts.