Re-imagining the city can be a provocation to reconsider and expand the range of possibilities for a city in the future. It can simply be an opportunity for an unfettered imagination physically to design something completely new and different, not tethered to the existing city. Or it can open the door to a fundamentally critical view of the existing city, questioning the social and economic and organizational principles that underlie its present constitution and are normally taken for granted. The best of classic utopias do both. What follows focuses only on the latter, on the imagining not of the physical but of the human principles and practices on which an imagined city could be based. It raises some critical questions about some of the principles and practices as they implicitly exist today and imagines some alternatives.

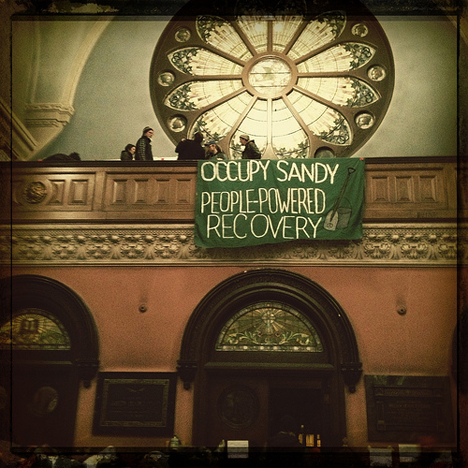

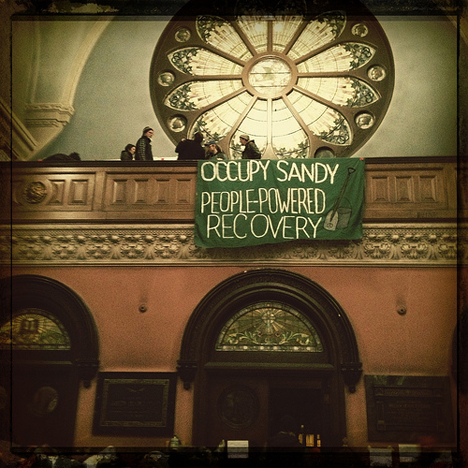

Photo: Bonnie Natko. Source:Flickr

If we were not concerned with the existing built environment of cities, but could mold a city from scratch, after our heart’s desire, Robert Park’s formulation that David Harvey is fond of quoting, how would such a city look? Or rather: according to what principles would it be organized? For its detailed look, its physical design, should only evolve after the principles it is to serve have been agreed upon. So what, in our heart of hearts, should determine what a city is and does?

The world of work and the world of freedom

Why not start, first, by taking the question literally. Suppose we had neither physical nor economic constraints, what would we want, in our hearts? Never mind that the supposition posits a utopia; it is a thought experiment that may awaken some questions whose answers might in fact influence what we do today, in the real world, on the way to an imagined other world that we might want to strive to make possible.

It may be hard to imagine such a counterfactual, but there are three approaches, based on what in fact we already know and want today. The first two rest on a single distinction, that between the world of work and the world outside of work, a key division that underlies how we plan and build our cities today, a division that largely parallels that between, as various philosophers have phrased it, the system world and the lifeworld, the realm of necessity and the realm of freedom, the world of the economy and the world of private life, roughly the commercial zones and the residential zones. One approach is then to imagine reducing the realm of necessity; the other is to imagine expanding the realm of freedom.

Most of us probably spend close to a majority of our time in the world of work, in the realm of necessity; our free time is the time we have after work is over. Logically, if the city could help reduce what we do in the realm of necessity, our free time would increase and our happiness too.

Shrinking the realm of necessity

Suppose we re-examine the composition of the world of necessity that we now take for granted. How much of what is there now is really necessary? Do we need all the advertising billboards, the flashing neon lights, the studios for the advertising agencies, the offices for the merger specialists, for the real estate speculators, for the high-speed traders, the trading floors for the speculators, the commercial spaces devoted solely to the accumulation of wealth, the consultants helping to make unproductive activities produce only more wealth, not goods or services that people actually use? If we do not need all of them, do we need all the offices for the government employees regulating them? Do we need all the gas stations, all the automotive repair and servicing facilities, all the through streets to serve all the cars we would not need if we had comprehensive public transit? Do we need all the jails and prisons and criminal courts? Are these parts of the realm of necessity today that are really necessary?

How about the ultra-luxury aspects of the city today? How do we see the multi-story penthouses in Donald Trump’s buildings? The virtually fortified enclaves of the rich in high-rise enclaves in our city centres, the gated communities with their private security in our inner and outer suburbs? The exclusive private clubs, expensive private health facilities, ostentatious lobbies and gateways and grounds where only the very rich can live? Are McMansions and true mansions necessary parts of the realm of necessity? If conspicuous consumption, á la Veblen, or positional goods, are in fact necessary for the well-being of their users, then something is wrong here: surely such marks of status, such conspicuous consumption cannot ultimately be as satisfying for its beneficiary as other, more socially rich and personally productive and creative objects and activities might. Or are these expensive attributes of wealth part of the real freedom of their possessors? But the realm of freedom is not a realm in which anything goes: it does not encompass the freedom to harm others, to steal, to destroy, to pollute, to waste resources. Imagine a city where there are limits on such things, in the public interest, freely and democratically determined, but in which what is provided for (but all of it) is what is really necessary for a meaningful freedom to be enjoyed.

Conclusion: The realm of necessary work could be shrunk significantly without any significant negative impact on a desirable realm of freedom.

Freely doing the necessary

A second way the necessary world of work could be reduced would be if some of what is in it that is truly necessary could be freely done, moved into the world of freedom. If in our imagined city what we do in the world of work could be converted into something that would contribute to our happiness, we’d be way ahead of the game. Is that possible – that we would do some of our presently unpleasant work freely, enjoy our work as much as we enjoy what we do outside of work? That we would in fact at the same time reduce the amount of work that is really necessary, and also convert much of the remainder into work that is done freely, in fact into part of the realm of freedom? And if so, could a city contribute to making that possible?

But why do such unpleasant tasks make us “unhappy” anyway? Couldn’t some work that is now being done only because it’s paid for, unhappily at least in the sense of not voluntarily done but only done because of the necessity of making a living, also be done by volunteers, under the right conditions? And even provide happiness to those doing it? The Occupy Sandy movement formed at the end of 2012 in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy provides some hints to this end.

In Occupy Sandy, volunteers went to areas devastated by Hurricane Sandy to distribute food and clothing and help folk made homeless find shelter, water, childcare and whatever was needed. Many veterans of Occupy Wall Street and other occupations did this, not to build support for the Occupy movement, but out of the simple desire to help fellow human beings in need. It’s part of what being human is all about. It’s been discussed, as part of what sociologists call the “gift relationship” (Titmuss 1970), but not the relationship of giving where you expect something in return, like exchanging gifts with others at Christmas, and it’s not just with people you know, but with strangers. It’s an expression of solidarity: it says, essentially, in this place, this city, at this time, there are no strangers. We are a community, we help one another without being asked, we want to help each other, we stand in solidarity with each other, we are all parts of one whole; that’s why we bring food and blankets and moral support. The feeling of happiness, of satisfaction, that such acts of solidarity and humanity prompt are what a re-imagined city should provide. A city where no one is a stranger is a profoundly happy city.

Imagine a city in which such relationships are not only fostered, but ultimately become the whole basis for society, replacing the profit motive for personal actions with the motivation of solidarity and friendship and the sheer pleasure of work. Think of all we already do voluntarily today that is really, in the conventional sense, work. Imagine something very concrete, something maybe very unlikely but not so difficult to imagine. Imagine what you would do if you didn’t have to work, but were guaranteed a decent standard of living; think of all the voluntary organizations we belong to (de Tocqueville noticed that long ago), the collective way houses were built and roofs raised in the early days of the United States; the clubs, the street parties, the volunteers staffing hospitals and shelters, the Occupiers of all sorts doing what is really social work as part of their freely given support for the movement, the houses built by volunteers with Habitat for Humanity. Think of volunteers directing traffic in a blackout, sharing generators when the power goes off, giving food to the hungry. In many religions, caring for the stranger is among the highest of virtues. And think of artists doing chalk pictures in the sidewalk, actors putting on street performances, musicians playing publicly for pleasure as much as for donations. Think of all the political activity that we engage in without any expectation of return other than a better city or country. Think of all that retired folk do voluntarily that they used to be paid for: teachers tutoring students, literacy volunteers helping immigrants, women who had worked at home and still do, helping in the kitchens of shelters and community clubs, volunteers cleaning trash on trails and roadsides. Think of all the young people helping their elders to master new technologies. Isn’t the city we want to imagine one where these relationships are dominant, and the profit relationship, the mercenary relationships, the quest for profits and ever more goods and money and power, were not what drove the society? Where the happiness of each was the condition for the happiness of all, and the happiness of all was the condition for the happiness of each?

Some things in the realm of necessity are really necessary, but are unpleasant, uncreative, repetitive, dirty

– yet get done today because someone gets paid to do them and is dependent on doing them for a living, not because they get any pleasure out of doing them. Part of the work done in the realm of necessity is not really necessary, as argued above. But some is: dirty work, hard work, dangerous work, stultifying work: cleaning streets, digging trenches, hauling cargo, aspects of personal care or treatment of diseases, garbage collection, mail delivery – even parts of otherwise rewarding activities, like grading papers for teachers, cleaning hospitals, copying drawings for architects or fussing with computers for writers today. Could any of this be freely done if the conditions were right? Some of this work can undoubtedly be further mechanized or automated, and the level of unskilled work is already steadily being reduced, but it is probably a fantasy that all unpleasant work could be mechanized. Some hard core will remain for some unhappy soul to do.

But as for such pure grudge work, would not the attitude towards doing it be much less resentful, much less unhappy, if it were fairly shared, recognized as needed and efficiently organized? In some social housing estates in Europe, tenants were accustomed to sharing the responsibility for keeping their common areas clean such as the landing in their staircases, their entries, their landscaping. They were satisfied that it was properly organized and both the assignment of tasks and the delineation of physical spaces was something worked out collectively (in theory, at least!) and generally accepted as appropriate. Most took pride in this unpaid, unskilled work; it was an act of neighbourliness. Once we watched a fast-order cook flip pancakes, tossing them in the air to turn them over, grinning as he served them to an appreciative diner. Craftspeople traditionally took pride in their work; today there are probably as many hobby potters as there are workers in pottery factories. If such facilities were widely available in a city, might not many people even make their own dishes out of clay, even while automated factories mass-produced ones out of plastic?

So one route to re-imagining the city from scratch is to imagine a city where as many of the things that are now done for profit, motivated by exchange, competed over for personal gain in money or power or status, or driven by necessity alone – as many of these as possible are done out of solidarity, out of love, out of happiness at the happiness of others. And then imagine all the things we would change…

To put the challenge of re-imagining a city most simply: if a city could be fashioned for the purposes of the enjoyment of life, rather than for the purposes of the unwelcome but necessary activities involved in earning a living, what would that city be like? At a minimum, wouldn’t it shift the priorities in the uses of the city from those geared to “business” activities, those pursued purely for profit in “business” districts, to those activities done for pleasure and their innate satisfaction, in districts designed around the enhancement of residential and community activities?

Expanding the realm of freedom

As an alternative way of re-imagining, a city could also be re-imagined based on the day-to-day experience of everything that already exists in the realm of freedom in the city as we now know it. Taking this as our point of departure, which other facilities necessary to sustain the realm of freedom in the re-imagined city would have to be made available? Community meeting places, smaller schools, community dining facilities, hobby workshops, nature retreats, public playgrounds and sport facilities, venues for professional and amateur theatres and concerts, health clinics – the things really necessary in a realm of freedom?

We might give the possibilities shape by examining how we would actually use the city today, were we not principally concerned with making a living but rather with enjoying being alive, doing those things that really satisfy us and give us a feeling of accomplishment. What would we do? How would we spend our time? Where would we go? In what kind of place would we want to be?

One could divide what we do into two parts: what we do privately, when we are alone or just with our intimately loved ones, and what we do socially, with others, beyond our core and intimate inner circle. The city we then imagine would ensure each has the first, the space and the means for

the private, and that the second, the space and the means for the social, are collectively provided. For the first, the private, what the city must provide is protection for space and activities that are personal. The second, the social, is what cities are really for, and should be their main function. Cities, after all, are essentially defined as places of wide and dense social interaction.

Many of the things we already do, when we are really free to choose, we would continue to do in our re-imagined city – and, possibly, if one is lucky, they might be some things one already gets paid to do now. Some of us love to teach; if we didn’t have to earn a living, I think we’d like to teach anyway. We might not want to have a 9:00 a.m. class, or to do it all day or every day; but some we’d do for the love of doing it. Many of us cook at least a meal a day, without getting paid for it; would we maybe cook for a whole bunch of guests in a restaurant if we could do it on our own terms, didn’t need the money, and weren’t getting paid? Would we travel? Would we take others along if we had room? Entertain guests, strangers, from time to time, out of friendliness and curiosity, without getting paid, if we didn’t need the money? Would we go to more meetings, or be more selective in the meetings we go to? Would we go for walks more often, enjoy the outdoors, see plays, act in plays, build things, design things, clothes or furniture or buildings, sing, dance, jump, run, if we didn’t have to work for a living? If none of the people we met were strangers, but some were very different from us, would we greet more people, make more friends, expand our understanding of others? Imagine all that, and then imagine what we would need to change in the city we already know to make all that possible.

What would that imagined city look like? Would it have more parks, more trees, more sidewalks? More schools, no jails; more places where privacy is protected, and more where you could meet strangers? More community rooms, more art workshops, more rehearsal and concert halls? More buildings built for effective use and aesthetic pleasure rather than for profit or status? Fewer resources used on advertising, on luxury goods, on conspicuous consumption?

What would it take to get such a city? Of course, the first thing is unfortunately very simple; we’d need the guaranteed standard of living, we’d need to be free of the need to do anything we didn’t like doing just to earn a living. But that’s actually not so impossible; there’s a whole literature on what automation could do, on the wastage inherent in our economies (23 per cent of the Federal budget goes to the military; suppose that money didn’t get paid for killing people but for helping them)? And wouldn’t we be willing to share the unpleasant work that remains if it were for the means to live in a city that was there to make us happy?

All that takes many changes, and not only changes in cities. But the thought experiment of imagining the possibilities might provide an incentive for actually putting the needed changes into effect.

From the real city to the re-imagined city: Transformative moves

Beyond thought experiments, provocative as they may be, what steps can be imagined that might pragmatically move us towards the re-imagined city of our heart’s desire? One approach might be to start by seeking out existing aspects of the city activities that already offend our hearts and moving to reduce them or those that already give us joy and moving to expand them.

If then we were to re-imagine the city pragmatically but critically, starting with what’s already there, the trick would be to focus on those programmes and proposals that are transformative, that deal with the root causes of problems and satisfactions, that are most likely to lead from the present towards what the city re-imagined from scratch might be. In other words, to formulate transformative demands, ones that go to the roots of problems, what André Gorz called non-reformist reforms.

It is fairly easy to agree on much that is wrong in our cities, and to go from there to agreement on what might be done in response; and then to put those pieces together, such that a re-imagined image of the city, perhaps not as shiny as one re-imagined from scratch but more immediately realistic and well worth pursuing, could emerge. Look individually at what those pieces might be. There are of course more, but the following are examples of key ones:

Inequality: We know high and rising levels of inequality are at the root of multiple tensions and insecurities in the city, and that a decent standard of living in the city depends on its residents having a decent income. Strong living wage laws, and progressive tax systems, are moves in that direction. The transformative demands here would be for a guaranteed minimum annual income for all, based on need rather than performance.

Housing: Decent housing for all and the elimination of homelessness, over-crowding and unaffordable rents, would be key ingredients in any properly re-imagined city. Housing vouchers, various forms of subsidies, even tax incentives, zoning bonuses for mixed-rental construction, are all moves towards ameliorating the problem. For homes threatened with foreclosure, reducing principal or interest and extending payments is helpful short-term, but likewise does not deal with the underlying problem. Transformative, however, would be the expansion of public housing, run with the full participation of tenants and sustained at a level of quality such that removes any stigma from its residents. Community land trusts and limited-equity housing likewise points the way to replacing the speculative and profit-motivated component of housing occupancy with use value, and stressing the community ingredient in housing arrangements.

Pollution and congestion: Automobile fumes, congestion, the inaccessibility except by car of basic services can all be serious problems, and regulating emission levels on cars and congestion pricing are useful means of ameliorating the problem. Transformative are measures such as closing streets (the Times Square experiment vastly expanded), and running much improved pubic mass transport, encouraging the adaptation of heavy usage areas to support bicycle access; all of which goes further in attacking the roots of the problem, further towards re-imagined cities.

Planning: The lack of control over one’s environment, the difficulties of participating actively in decisions on the future of the city in which one lives, is a major issue if the quest is for happiness and satisfaction in the re-imagined city. Public hearings, the ready availability of information, transparency in the decision-making process, empowered community boards are all means of enhancing the level of public control. But until community boards are given some real power, rather than being merely advisory, alienated planning will continue. Real decentralization would be transformative. The experiment in participatory budgeting now under way in New York City and elsewhere is a real contribution to potentially transformative policies.

Public Space: After the experience of the evictions from Zuccotti Park, the need for public space available for democratic action has become manifest. Adjusting the rules and regulations governing municipal parks, permitting more space, public and public/private, to be available for such activities, are steps in the right direction. Protecting the right of the homeless to sleep on park benches is a minimalist, although basic, demand, obviously not a demand aimed at ending homelessness. Expanding the provision of public space and prioritizing its use for democratic activities can be transformative, and would be a component of any re-imagined city.

Education: Adequately funded public education, with the flexibility of charter schools but without their diminution of the role of public control, would be a major step forward; for students presently in higher education striking out debt incurred through student loans is a pressing demand. But the transformative demand would be for totally free higher education, available to all, with the supportive conditions that would permit all students to benefit from it.

Civil Rights: Organization is a key factor in moving towards an imagined transformed city, and the city of the present should facilitate democratic organization. Other issues mentioned above: public space, education, housing and incomes making real participation feasible, are all supportive of an expanded conception of civil rights. So, clearly, is the end of many practices restricting organization: from police limitations on assembly and speech to so-called “homeland security” measures to the simple use of the streets for public assemblies, leafleting and so on. Transformative here would be overarching measures seriously limiting the unfortunately inevitable tendency of government officials and leaders to try to control critical activities within their jurisdictions, critical activities sure to be found short of the achievement of the re-imagined city, and perhaps even there.

Put the goals of all such transformative demands together, and you have transformed a purely imagined city into a developing and changing mosaic based on the existing: slowly flesh will grow on the bones of what imagination generates.

NOTE

A warning: re-imagining the city can be fun, it can be inspirational, it can show doubters that another world is possible. But there is a danger: re-imagining the city should not be seen as a current design project, laying out what the physical city could look like if we had our way, what utopia would look like. What the city needs is not redesign, but reorganization, a change in who it serves, not how it serves those who now are served by it. It needs a different role for its built environment, with changes adapted to the new role, not vice versa. A re-designed city is a means to an end. The end is the welfare, the happiness, the deep satisfaction, of those whom the city should serve: all of us. We should not spend much time physically designing what those re-imagined cities would look like except as a provocation to thought, for which however they are useful – and which is the intent of this piece. The actual designs should be done only when there is actually the power to implement them, by the people who would then use it. Designs should be developed through democratic and transparent and informed processes.

Bibliography

Brynjolfsson, Erik and Adam McAfee, Race Against The Machine: How the Digital Revolution is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy, Digital Frontier Press, 2011.

Kellner, Douglas (ed.), Herbert Marcuse: Marxism, Revolution and Utopia, Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse VI, Routledge, forthcoming.

Marcuse, Herbert, Essay on Liberation, Beacon Press, 1969.

Titmuss, Richard (1970): The Gift Relationship: From Human Blood to Social Policy, Allen and Unwin, 1979.