The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.

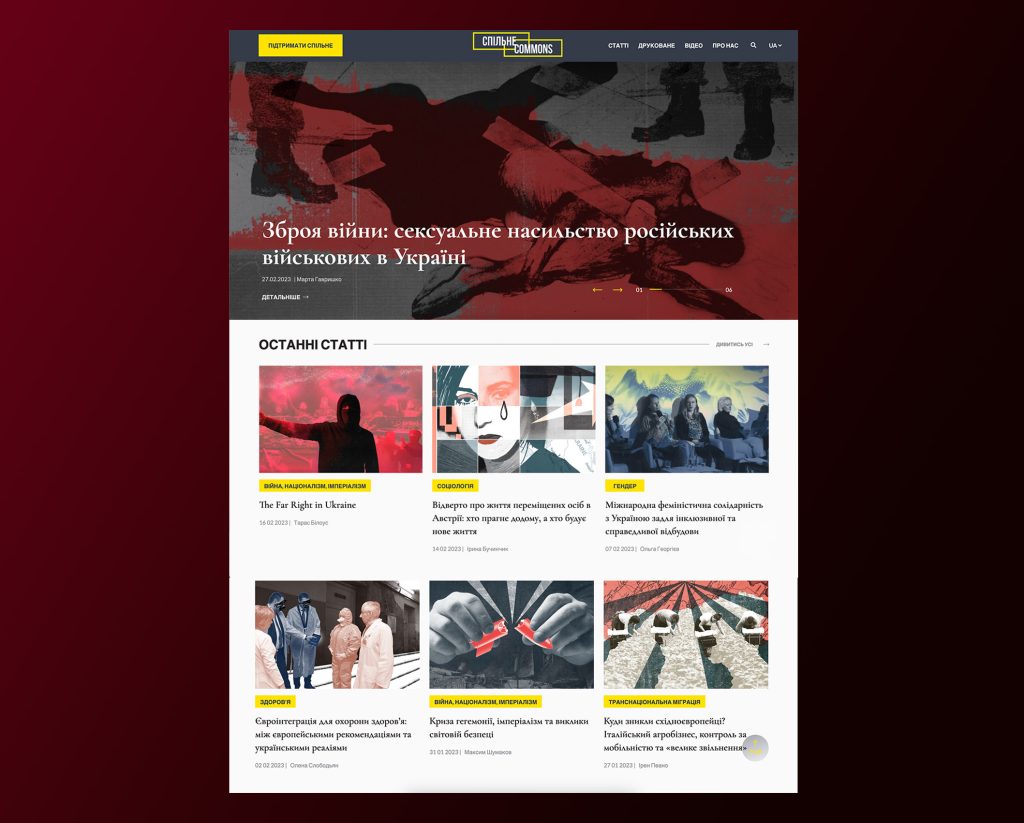

Sexual violence as a Russian weapon of war: exceptional brutality and widespread use as means of terrorising the Ukrainian population. Also: ambivalent attitudes to home among Ukrainian refugees; and women’s voices on the reconstruction debate.

In a powerful and distressing piece for Spilne, Marta Havryshko explains why the sexual violence being carried out by the Russian military is not simply a ‘by-product’ of bad discipline, or an abuse of power. Three features define its use as a weapon of war since 24 February 2022.

First, sexual violence is widespread. The 155 cases currently being investigated by Ukraine’s Prosecutor General represent the tip of the iceberg. Evidence of such crimes is being collected not only by Ukrainians, but also by international organisations such as the UN and Amnesty international, as well as foreign media. Intercepted recordings of Russian military calls also capture soldiers discussing sexual crimes.

However, many survivors do not want to testify about their experiences, fearing stigmatisation, traumatic memories, an untrustworthy legal system, or the return of Russian occupiers. The true number of victims likely runs into the thousands.

Second, sexual violence is being used as a ‘weapon of terror’ against the entire population in occupied territories. Women and men have been targeted. The youngest known victim is four years old. Amongst the oldest are women in their eighties.

Finally, the brutality is exceptional. Havryshko cites cases where victims were abused and tortured for hours, days and even weeks. Multiple perpetrators assault single individuals. To achieve maximum impact, Russian soldiers carry out this violence ‘in the presence of family, friends, neighbours or other people who are with the victim in hiding or in places of detention’. This amplifies the suffering of the victim and has the effect of deeply traumatising families and communities.

Taken together, the scale, brutality and systematic use of sexual violence by the Russian military in Ukraine testify to ‘the conscious and purposeful use of social violence in order to achieve the military and political goals of the Russian leadership’.

Iryna Buchynchyk writes about the aspirations of Ukrainian refugees who have escaped to Austria. Ninety thousand are officially registered – primarily women and children. Under martial law, most Ukrainian men aged 18–60 are not allowed to leave the country.

Citing a survey conducted by Austrian institutions between April – June 2022, Buchynchyk explains that these refugees’ plans for the future vary. Thirty-four percent want to return home as soon as the war ends. Twenty-five percent said they may return, if the war ends, and 27% don’t know. Six percent said they would return to Ukraine even if the war continues, and 8% said they would remain abroad, as they had nowhere to return to.

Supplementing the survey data with her own interviews, Buchynchyk highlights the struggles of Ukrainian refugee women. Many report being exhausted from worry. They live in a suspended state, taking things ‘one day at a time’. One told her, ‘I’ll deal with problems of integration later, when I start to live. So far I’m surviving.’ Another explained, ‘Vienna isn’t bad … but home is home. I’m a stranger here’.

Securing safety for their children was a key motivating factor for many women: ‘I am here only because it was necessary to provide safety for my child.’ Single women spoke of their desire to return to Ukraine, but acknowledged that if they meet someone and start a family whilst abroad, they may well stay. ‘A home is a home, but you have to build your own future.’

The author stresses that all her interviewees understood their privilege in living in safety. They appreciate the help and support that they have received from the society that has welcomed them. But this doesn’t mean that the pull of home wanes: ‘I can’t plan far. However, I am drawn home … I know some people have already burned all bridges, they said: we are staying here one hundred percent. I’m not. I don’t want to, because I love Ukraine very much.’

Olha Heorhyev summarises a panel on ‘Transnational feminist solidarity in support of the reconstruction and struggle of Ukraine’ in the Czech Republic. Speakers from Ukraine and central Europe tackled misunderstandings of the war amongst western feminists and leftists, who have criticized military support.

Sociologist Oksana Dutchak condemned the ignorance of those who engage in ‘abstract geopolitical analysis’ and do not recognize Ukraine’s right to resist imperialist aggression and ‘the right of women to independently determine their needs, political goals and strategies to achieve them’.

The war highlights the need for a new, fair security system in the region that can combat imperialist aggression. ‘Any criticism of NATO and similar structures must take into account the interests of small states, for which such military and defence groups are vital’, explains Heorhyev.

Discussions also centred on the importance of an equitable post-war future. Rebuilding Ukraine’s economy should not happen at the expense of health and social care. Further liberalization of the labour market and the reduction of welfare provision may lead to further destabilisation for Ukrainian women already marginalised in the country’s labour market. Women’s voices must be heard in ongoing debates about paths to reconstruction.

Published 2 March 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Spilne © Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?