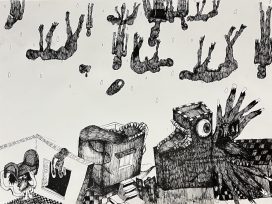

The representation of Slovenia at the 54th Venice Biennale – the oldest and undoubtedly most prestigious international event in the world of art – has never caused as much media controversy as this year. Criticism have been voiced in daily newspapers regarding both the relevance of the sculptures by Mirka Bratusa as well as their gallery presentation. There is no doubt that Bratusa’s sculpture installation (Heaters for Hot Feelings) – which first part (The Hypocrites) stood out as one of the best presented displays when it was exhibited in the monastery church in Kostanjevica na Krki – is sufficiently contemporary, representative, and original to deserve presentation in an international setting.

Of course, agreement or disagreement with the selection of the project is a matter of subjective evaluation. But far more questionable is the transfer of these monumental sculptures from the space of the church interior to the setting in Venice which has (again and again) clearly demonstrated something that has been known for a long time: Gallery A+A is not suited to the presentation of relevant artistic projects. Specifically, the gallery that the Slovenian government has leased for the promotion of Slovenian artists abroad and which during the time of the art and architectural Biennale was changed into a national pavilion, located in the vicinity of the famous Palazzo Grassi which attracts hordes of visitors during exhibition events, is squeezed into a very narrow, barely meter-wide alley in which two grown people can hardly fit. Similar to this “anteroom”, its interior is also cramped, composed as it is of several spaces connected by narrow passages. In short, the gallery is considered by artists to be an exceptionally unappealing and problematic space where it is no easy task to prepare a quality exhibition intended to compete for international recognition in an almost unmanageable mass of visual production such as that offered up with every Biennale manifestation. The Venice Biennale preserves its traditional structure, which despite the presence of a central curatorial exhibition is based on the showcasing of artistic achievements of particular countries and has a competitive nature.

In the given situation it appears almost self-evident that the spatial predispositions of the gallery should have been taken into account already in the selection of the project, or at least the extent of its (non)adaptability partially anticipated. When the selection of the project was announced, it was stated that the (approximately) two-meter high clay sculpture The Hypocrites “are special also because they function differently in different settings” and that “in Venice they will function as humorous figures”. Clearly no one considered the possibility that they would “adapt” to the Venice ambience to such an extent that they would themselves appear cramped and compressed. Heaters for Hot Feelings (the warm Hypocrites and the cold sculptures in vegetable forms connected through pipelines into a network of bodies, in which some provide heating and others cooling) thus, despite a clear conceptual basis (a metaphorical expression of the mutual interdependence of social structures) and consistent sculptural design, do not function as a whole the way they should, and do not attract as much attention as they could.

It is well known that individual Slovenian artists in previous editions of the Biennale have already realized their projects in other Venice locations. Would it not therefore be more appropriate if the state found a more suitable space for international exhibitions and specific ambient displays? Just to be clear, we are not talking about prestige, or ostentatious displays in some luxurious Venetian palace: this is actually not a rarity at the Biennale. We are talking about the attitude towards the selected authors cooperating in such a manifestation, also so that the work of the artists would be rewarded and the financial investments used more efficiently. The space itself of course is no guarantee of higher quality of exhibitions, nor of their visibility in the international arena. But it is an indisputable fact that all works of art, and especially classical sculptural artefacts, are experienced by the visitor in their relationship to space. Moreover, at the opening of the pavilion we learned that the lease for the space in which Gallery A+A has been housed since 1998 is expiring, which serves as an additional incentive for serious consideration of its possible relocation.

Reflections on the suitability of and need for the Venice exhibition space almost automatically raise two crucial questions: to what extent is the state, which does not provide suitable conditions and a stable environment even at home, willing to invest in the promotion of Slovenian culture and arts abroad, and what space does cultural promotion have in the state structure? It should be noted that the Venice Biennale is the only one in a multitude of colossal visual arts events that preserves national foundations in its basic structure. Despite many criticisms that it does not follow contemporary processes in a globalized society, that it does not reflect current social problems, that it is too loosely conceived, and is (in the style of the overproduction of goods) experiencing uncontrolled growth, it is nevertheless the only opportunity for the presentation of contemporary art for those countries in which the art market is undeveloped or only in its infancy. Among these are Slovenia, a country (with the exception of rare individuals) insufficiently aware of the problem of poor international connections, an undeveloped system of artistic exchanges, and consequently inadequate recognition abroad. The introduction of a “cultural allowance” for the promotion of domestic art intended to become an important element of foreign policy and contribute to the reputation of Slovenia, does indicate that there have been some shifts in this area – but whether for the better only time will tell. However, this funding (as far as is known) is reserved only for those artistic projects that are to be presented at diplomatic missions and consulates around the world.

This year’s opening of the Slovenian pavilion also testifies as to how much attention is paid to establishing intercultural contacts. It is not an unimportant detail but an opportunity which could be used to great advantage as a springboard for greater visibility. During the three opening days, everyone who is anyone in the international world of art comes to Venice. Due to the shortage of space, the Slovenian pavilion has several times located its opening ceremony in the nearby square, but this year it took place in the gallery itself, into which a horde of cultural enthusiasts squeezed, spilling over into the narrow alley in front of it. Many potential visitors that Bratusa’s sculptures might have attracted and who might have viewed the exhibition pushed past due to the intolerable crowding and stuffy atmosphere in the gallery.

So what sort of impression of the status of Slovenian visual arts in the social sphere did random passers-by gain? That it is a marginal “thing” and that we actually do not know precisely why we would even promote it. True, we are in a recession, but believe me: the spectacular openings of almost 90 participating countries and huge number of accompanying events, one after another, gave just the opposite impression, namely one of global abundance. The pomp that in many instances overshadows the point of the manifestation, which is supposed to be cultural, is of course not a feature of the Biennale. But nevertheless one cannot avoid thinking that this time the Slovenian event was a reflection of the unenviable position of domestic contemporary art which has the “status” (almost) of an unnecessary social pillar.

At the same time it reflects the conflict-ridden state of the Slovenian cultural milieu. It certainly does not advance the cause of promoting a national presentation. Yet nevertheless it seems as though it could show a lot more to the international audience. We have the potential but not the right vision nor suitable support. In this context the choice of Bratusa’s Heaters for Hot Feelings is indeed the right one: it can be understood not only as a metaphor of humans’ “feeling of being lost in culture” but also that Slovenian cultural policy has itself lost its way.