Prized possessions

Ágnes Heller, Krzysztof Michalski, Miriam Rasch and the wisdom we borrow

No wonder many in the social sciences advocate the reverse: instead of operationalizing and uniformizing human beings, we need to improve our understanding of the differences that create often lethal inequalities – those, for instance, that Daniel Trilling describes in his article on the over-policing of European Roma and homeless people during the corona crisis.

Internet Archive Book Images / No restrictions via Wikimedia Commons. Adaption: Eurozine logo has been placed over the image.

The concept of ‘friction’ to describe the unexpected, unruly, non-conforming or inoperative can help expose dataism’s self-referentiality, writes Miriam Rasch. Data relies on human perception, a highly unstable process. Questions asked and metrics used determine the kind of information that is generated; in a mathematicised environment, the robust ecosystem of knowledge and perspectives that diverse humans can produce, are inevitably lost. These, however, are the qualities we need to transform societies from inhumane machines into functioning communities.

Delving into personal fallibilities is pretty much cultural journalism’s territory. The capacity for discretion is what makes us human, and death is ‘not a limitation of our humanness, not a prison of the soul, but rather that which reveals the authentic meaning of human existence as freedom’, writes Marci Shore in a sidenote to the philosopher Krzysztof Michalski’s posthumous essay ‘The quietness of death’. Michalski’s distilled, dark yet very clear tone is much needed in today, when the prospect of death is much closer than usual.

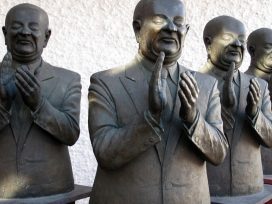

Clapping is merely a way to compensate those who face a pandemic threat without appropriate protection, so that those who applaud them may enjoy comfort and safety, Christian Juri argues.

It’s not the first time a disease brings globalisation to a halt: Ulrich Menzel reminds how the black plague stopped global trade for an entire century and reviews how the current crisis could alter our societies.

The last time death and personal loss defined humanity’s perception this much was during the Second World War. The 75th anniversary of Victory Day, the end of WWII in Europe, was celebrated last week. Mischa Gabowitsch describes the changing functions of the commemoration of Victory Day in the (post-)Soviet space from the 1950s to the present, while Tatiana Zhurzhenko surveys memory wars between Ukraine and Russia over the meaning of the victory over fascism. And, in an interview for our partner journal New Eastern Europe, Erneszt Wiciszkiewicz talks about the Kremlin’s culture wars on the Polish front.

Ágnes Heller, the Hungarian philosopher, was born 91 years ago on 12 May. This is the first time we celebrate without her. Heller’s body of work encompasses a wide spectrum of positions, not to say contradictions. In that, she truly is the best student of György Lukács, whose famous adage ‘My thoughts from yesterday I leave to my friends’ characterized his relationship to his own legacy and the controversies therein. Heller was not this generous with her own work but, instead, gladly addressed and owned her own meanderings (‘a vargabetűit’, as Hungarians say).

She was, most of all, a teacher: a figure who embodied an heirloom of the twentieth century. A passionate debater, she disregarded rank when engaging in an argument and was open to anyone’s ideas, as long as they were of merit and substance. That is a rare feature for someone of her stature. What drove her was a deep and determined hope: one that does not lie in false comfort or weak optimism but demands thought and effort towards reshaping the world in its image’, write Shalini Randeria and Ludger Hagedorn, honouring Heller’s memory.

My personal fascination with Heller has to do with her extraordinary ability to convey compound and often conflicting notions in a language that was accessible and tangible for lay audiences too, but without dumbing or numbing it down. She attributed this to her years of experience as a schoolteacher: her eye was trained to seek the potential in pupils.

Heller’s tenacious love for life – ‘Amor Mundi’, another thing she shared with Hannah Arendt, besides their university chair at the New School – was a force that drew many to her, even if we didn’t agree with her on crucial points. In a world where heroes tend to be larger than life, and can quickly prove unworthy of admiration, this short woman stood tall on a pedestal built from her humanity, her acceptance and love for fallible humans. It was her passion to help them better themselves – not through medical interventions, automation or uniformization – but via Sophia, the most prized possession of a philosopher.

This editorial is part of our 9/2020 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 14 May 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Complexity

Wespennest 188 (2025)

In Wespennest: On the definition of hyper-complex systems; why keeping it simple is not always good political communication; how complexity became the hallmark of the musical avant-garde; and how new genres and platforms are making our interaction with literature more complex than ever.

What happens to democracy when governments court the rich and highly skilled, offering citizenship as privilege, when those in need are turned away? This year’s Speech to Europe takes the concept of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ migrants to task.