Preparing for the good times to be over

A month into Russia's invasion, is the EU ready for the challenge?

Russia’s war on Ukraine is clearly an attack on the whole of Europe, but domestic responses are still stuck with the narrative of patriarchal solidarity and the concern for consumer comfort on the home front. Philipp Ther argues for active solidarity, and with it, to prepare for the end of the convenience Europe has known: it may hurt, but without it, the long-term losses to freedom and welfare are likely to be higher.

The military attack on Ukraine seems to be stalled around Kyiv and the northern frontlines. The latest Russian announcements suggest the invasion may take a turn. Yet the hopes of the defenders may turn out to be premature, especially on the political battlefields and if one looks beyond Ukraine. The EU and its central economic power Germany have not yet fully understood that this conflict is not limited to the battlefields of Ukraine, and that they have been attacked as well. The lack of awareness became most obvious after the speech by Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky to the German parliament, which rejected a debate, referring to its set agenda for the day.

Austria’s fake memories

The Austrian reaction is even more embarrassing. Here the Social Democratic Party and the right-wing populist Freedom Party refused to invite Zelensky to give a speech, arguing that this would endanger Austrian neutrality.

A rebuttal of Ukraine was to be expected from the notoriously putinophile FPÖ, but it is shocking how the SPÖ still clings to old leftist narratives that Austria was liberated by Russians, regained its statehood from Russia (which is constantly conflated with the Soviet Union) and therefore has to be eternally grateful.

The fact that a high share of Ukrainian soldiers and battalions liberated Austria in 1945 and that Austrian soldiers serving in the Wehrmacht played their part in devastating Ukraine during World War II is still forgotten.

German hesitancy

The German government is clearly not up to the current challenges either. Chancellor Olaf Scholz gave an assertive speech on the third day of the war against Ukraine declaring a turnaround in German foreign policy that included stopping the North Stream 2 pipeline – which should never have been built anyway after the first Russian attack on Ukraine in 2014. He also announced full participation in economic sanctions, and supplying weapons to the Ukrainian army.

But since then, the debate on the war has stalled. The Liberal finance minister and chairman of the Liberal Party Christian Lindner is demanding a hefty discount on gas, as if the state could solve the problems of the energy markets. The economics minister and chairman of the Green Party Robert Habeck is warning against the impact of stiffer sanctions and an embargo against Russian gas and oil. Meanwhile, the chancellor is generally keeping a low profile and giving reassuring statements assuaging German angst that Nato might be drawn into the war.

Meanwhile, the payments for Russian energy have risen almost threefold compared to February 2021 and keep on oiling Putin’s war machinery with 700 million US dollars a day. Putin has even taken the initiative against Western sanctions by demanding one month after the start of the war that Russian oil and gas must be paid for in rubles. This would resurrect the full convertibility of the Russian currency and partially offset the Russian Federation’s exclusion from the international payment system Swift.

Losing moral leadership

The hesitant German reactions to this move reveal that the economic superpower has not yet understood that by attacking Ukraine Putin has also declared war on the EU and NATO. Moreover, this shrewd move allows Putin to test how susceptible the EU and particularly Germany are to blackmail.

Hence it was the right decision by the Polish, Czech, and Slovenian prime ministers not to bother asking a prominent member of the German government to accompany them on their train ride to Kyiv, although that would have greatly increased the political impact of that courageous journey. Germany is no longer admired as an anchor of stability in East Central Europe, but seen as a saturated, self-centered, and even corrupt weakling.

This is how Jean Paul Sarte portrayed French society and politics in his novel Le sursis (there is a good English translation titled The Reprieve) on the eve of the fateful Munich Agreement in 1938, when the western powers of that time betrayed Czechoslovakia (Poland joined them soon thereafter by annexing the Czech part of Cieszyn/Těšín).

Those tough European winters

The West looks more united at the moment, and it is certainly stronger than the group of anti-fascist countries on the eve of World War II. But it remains to be seen how strong that unity will be if Putin makes the delivery of Russian energy next fall and winter conditional on giving up overt political and covert military support for Ukraine.

If he’s the one who stops the supply of gas and oil, it will have a different impact on the European home fronts than if the EU governments openly communicate that Putin has declared a war on us as well, and that strict countermeasures are needed in support of Ukraine, but for the sake of the EU.

Of course, western politicians have warned that the sanctions against Russia will come at a price, but that announcement was geared towards the future. Now the price might indeed have to be paid, and that will trigger conflicts between and within countries.

When it comes to sanctions, it is also important to switch perspectives. It may make sense to keep NATO out of Ukraine in order to prevent a Third World War, and therefore to refrain from declaring a no-fly zone as in Bosnia in 1993 or a humanitarian mission by the alliance. Yet, in Russian eyes, the Western sanctions are but a different form of warfare. By participating in the sanctions, not even Austria is neutral anymore.

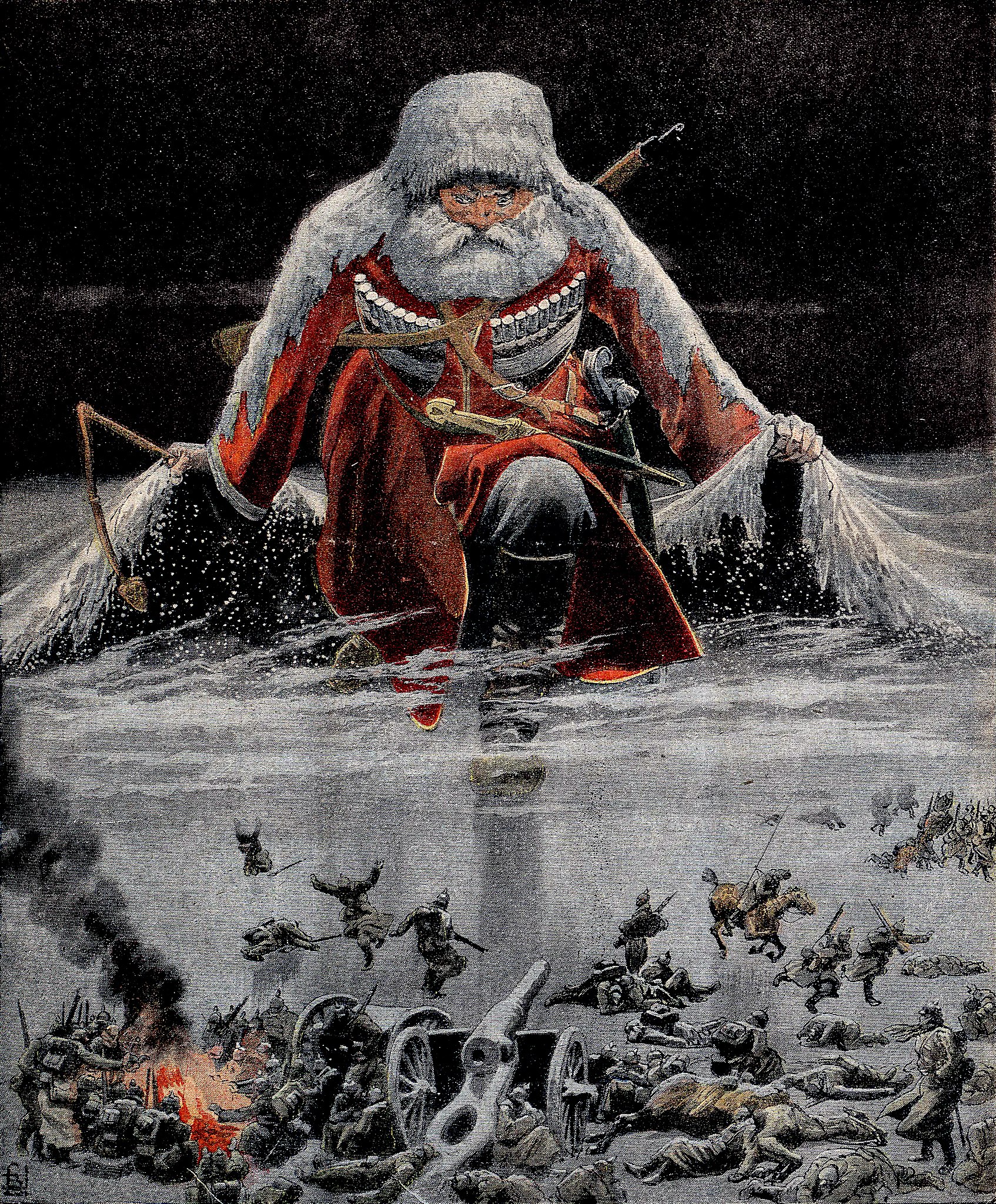

General Winter or General Frost is the mythical embodiment of the tough Russian winters that broke the backs of many conquerors. European leaders now fear their own winters, and how their electorate will cope without Russian energy imports. A retouched version of a 1916 graphic from the French ‘Le Petit Journal’. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Paralyzing the home front

The war is now moving closer to the EU anyway, in the form of the arrival of 3.5 million refugees. Seeing currently beleaguered cities such as Mariupol, one has to take into account Russian military action in Syria, and the course of the war in Bosnia in 1992/93, where half of the population was displaced. Extrapolating from these, the EU may expect at least 10 million refugees. Displacing masses of people and thus paralyzing the enemy is, like economic sanctions, another method of modern warfare that worked well when Hitler invaded France in the spring of 1940.

At the moment, Poland has received the most refugees from Ukraine. The motives for the Polish ‘open door’ policy are historically rooted in the motto ‘za wolność naszą i waszą’ (‘for our and your freedom’), one that was developed in 1830/31 to universalize the struggle against Russia. It did help the Polish insurgents to win European public opinion, like Zelensky does today, but it did not prevent the military collapse after around half a year.

The donations in the German Confederation helped the Poles reach their French exile, but the money came too late to buy weapons and deliver them to the insurgents. The PiS government, just like Hungary, is keeping its borders open also as a form of damage control, to repair the political losses done by their refusal to offer any help during the ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015/16 (a term already exaggerated, as I argued at the time in my history of refugees in modern Europe).

This move on their part even confirms the right-wing populist stance that every country can decide for itself which refugees and other migrants it accepts or rejects. The main argument for that has been a claim to preserve national sovereignty; it remains to be seen how active the sovranisti in Italy, Austria and elsewhere will become if the EU faces a severe energy crisis in the fall.

It is all the more urgent to concentrate on energy policy decisions on the European level, and not to repeat the fatal mistake with North Stream 2.

Compulsory gratitude

The solidarity with the refugees from Ukraine so far has been astounding. But is does not compensate for the lack of clear political support for Ukraine on other levels. Helping people in need is a great asset, yet the public support for refugees is likely to wane as more Ukrainians come and need to be housed, fed, and given access to the labour market.

Moreover, humanitarian support and politics cannot replace grave economic and political decisions that need to be made on our European home fronts. One should principally distinguish between patriarchal solidarity (such as donating worn clothes, furniture, and small amounts of money to charities), for which the recipients have to remain grateful and therefore in an inferior status, and active solidarity that is ready to make sacrifices and pursue clear political goals in cooperation with the recipients. This kind of solidarity may hurt for some months and maybe years, but if it is not provided, the long-term losses to our freedom and welfare are likely to be higher.

The minimum goal needs to be that Ukraine cannot lose this war, otherwise democracy will have lost against dictatorship. The EU too cannot lose this war because there is still Putin’s demand that NATO should retreat from Eastern Europe.

The good times are over

At the moment, it looks unlikely that the Russian army can conquer Ukraine and install a puppet government, but Russia might grab large territories, and lay waste to the rest of the country.

Who will be next, once Putin has reached his goals in Ukraine, at least partially? The Baltic countries with their Russian minorities, which are featured in Putin’s ‘ruskiy mir’? Or Poland, which a Russian leader certainly despises as much as Ukraine, legitimizing this sentiment with a blend of older imperial and Stalinist tropes? Putin has shown several times his ability for surprise attacks and military action. Even if his Blitzkrieg against Ukraine has failed, one never knows what his next goals and means of reaching them might be.

So far, no European leader has attempted to give a postmodern variant of Churchill’s ‘Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat’ speech of May 1940, three days after the German army had started its offensive against France. The situation is very different now, and professional historians should refrain from creating false or pallid historical analogies.

Yet I think the populace should be told again and again that this is a war on Europe (British media do that more than German or let alone Austrian media), and that active and long-term solidarity are needed now. That solidarity could start at the gas station, by turning down the heat at home, by preparing for the fall and winter instead of pretending that our lives can pretty much go on like they did before February 24. At the very start of the war, the message should have been that the good times are over for us now as well.

I very much hope that this active solidarity is being provided behind the scenes, something into which a historian writing about the present has little insight. I hope that military help and defensive weapons that prevent Kharkiv and other Ukrainian cities from suffering the fate of Mariupol are arriving in Ukraine.

If an ostensibly neutral country like Austria refrains from providing military support, it must compensate with more activities in other fields, such as supplying medical products to Ukraine. A historian’s quick glance at the map of Eastern Europe (and personal experience of travelling Ukraine by train and by road in the past 25 years) make it very clear how difficult it will be to provide Ukraine with the food, medical goods, energy, and weapons for a war that might drag on as long as the one in Bosnia.

Are we up for the challenge? History will relate.

Published 26 March 2022

Original in English

First published by Transformative Blog, RECET

Contributed by RECET © Philipp Ther / RECET / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

House keys recur in the stories of Crimean Tatars and Palestinians displaced from their respective homelands in the 1940s, and Ukrainian citizens fleeing Russian invasion since 2014. Ethnographic research and discourses on art and justice show how objects emblematic of home salvage the history of exiled peoples from oblivion.

As capital consolidates, culture recedes, funding vanishes, access narrows. The question persists: why fund culture at all? Cultural managers from Austria, Hungary and Serbia discuss.