Pessimism derives from pessimus, the Latin for ‘the worst’. In the days leading up to Turkey’s general and presidential elections on 28 May 2023, I tried to avoid pessimistes. I belonged to the ranks of those who believed optimus was fast approaching: a rebirth of parliamentary democracy, a return to human rights and reason, and, most importantly, a firm goodbye to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his bootlickers.

But now, three months later, I’m convinced that those who betted against Turkey’s autocrat in those hopeful days mostly did so out of cold calculation, not principle. Polls claimed the president was losing power, after all. Something mightier was in the making, a savvy new alliance preparing to grab power. Only losers would bid for a loser. Switching sides from the AK Party to the opposition alliance was a prerequisite for survival – a winner’s move that had little to do with ethics or political principles.

The opposition’s optimism in those days concealed, behind the liberal veneer, a thirst for power and a passion for revenge. Turkey’s opposition parties lost in May partly because of their lack of political principles. Since winning the election (the Islamist alliance gained 323 parliamentary seats out of 600), Erdoğan has weaponized the opposition’s hunger for power against its members: he knows it’s their Achilles’ heel.

The Turkish media, controlled by Erdoğan’s cronies, has painted opposition politicians as listless fools. Why, they ask rhetorically, did CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu lose? Because he doesn’t know how to wield power. And what about Meral Akşener, the leader of IYI? She doesn’t know either. So she didn’t deserve it.

Adapted by a photo by Imad Alassiry

And the rest? The Kurds, environmentalists, feminists, not to mention those hopeless Marxists? They can’t be allowed anywhere near real power, of course. But what about Ali Babacan, former minister of economy, or Ahmet Davutoğlu, former prime minister? They’ve only started opposing the AK Party in the past few years because they didn’t know how to stay in power, or because they became uneasy about holding it. Only Erdoğan knows how to wield power, retain it, and not be ashamed.

After twenty-one years in office (2002–2023), our hegemon is now showing the country and the whole world how to rule seemingly infinitely. Isn’t that a valuable lesson for our kids? Imitate our esteemed president and you won’t be bullied in the schoolyard. Learn to hold your ground by modelling yourself on our standoffish leader. Make peace with power. Embrace it. The world is a violent place, humans lead lonely existences, and anything is allowed in the struggle for survival. Without power, the nation grovels. Begs. Becomes servile. Those who willingly reject power are idiots. Those who can’t attain power deserve servitude.

This proto-fascist mentality reigned in Turkey in the 1920s when the Republic first emerged. It reigned in Turkey in the 1980s when I was a child and we lived under military rule. It continues to reign in Turkey today.

*

In my book The Lion and the Nightingale, I described those Turks who define themselves through power as lions: the domineering class that considers itself master and calls on people from all sectors to join its ranks and part ways with ‘losers’. Then there are Turkey’s nightingales: intellectuals, dissidents, artists and all the independent minds who undermine power structures through song, poetry and comedy, and who often face the prospect of penury or prison.

But while writing a preface for the paperback edition, I noticed how this year’s elections weren’t between lions and nightingales. They were a struggle between one tall roaring lion and a legion of aspiring lions who were trying to roar louder. Just look at Kılıçdaroğlu. The former social security specialist didn’t want to change the autocratic regime constructed by Erdoğan and his far-right coalition partners. He just wanted to change the person at the top. This became apparent when Kılıçdaroğlu refused to resign as leader of the CHP in the run-up to the elections. Had he been elected, Kılıçdaroğlu would now be leading both the country and his party, sustaining our Turkish style of Presidencialismo.

Does anyone remember Kılıçdaroğlu’s desperate position during the election’s tragic finale? On 23 May, he shook hands with the far-right firebrand Ümit Özdağ, a prominent hater of Kurds, socialists and Turkey’s 3.5 million immigrant community. For the aspiring president, the ends obviously justified the means. The so-called ‘Turkish Gandhi’ allegedly offered Özdağ’s party the posts of interior minister and head of intelligence. The duo smiled at cameras before instructing party members to cover thousands of billboards with their pledge to forcefully deport 15 million immigrants. Their slogan was ‘They. Will. Leave.’

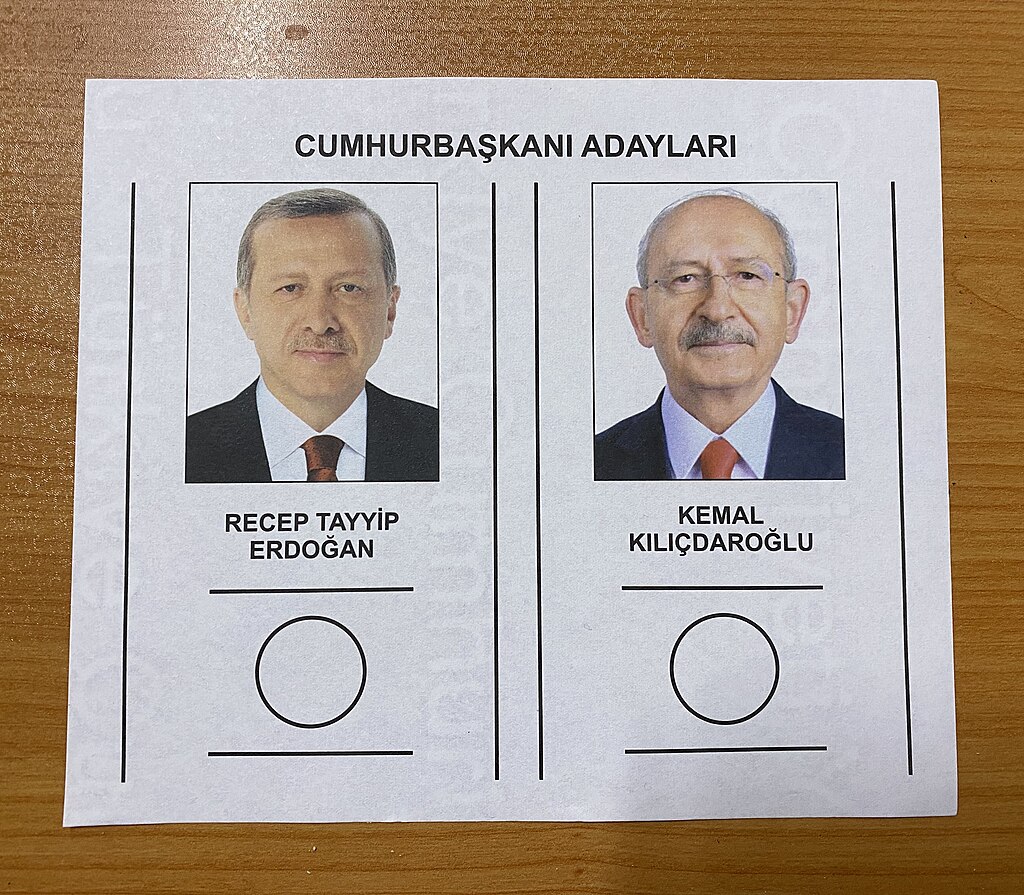

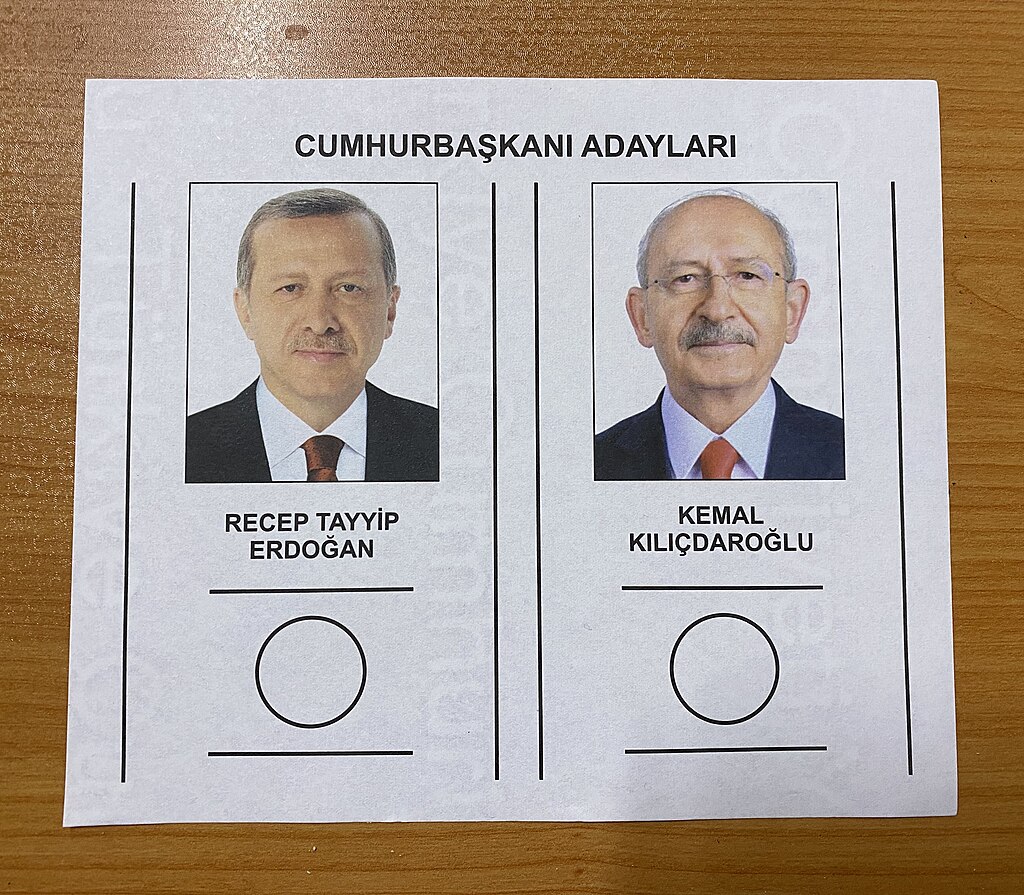

Ballot for the 2nd round of elections in Turkey, 2023 Photo by Kadı Kadı, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

We’re used to seeing Erdoğan and his cronies acting opportunistically. Over the past two decades Erdoğan has turned the country into his fiefdom: whatever he says, goes. He distributes the country’s riches to friends, family members and anyone willing to bow to his authority. He recently justified this behaviour by claiming that he was simply adapting the CHP model to the twenty-first century. Didn’t the founding party of the republic, during the height of its reign in the 1930s, have a free hand to jail professors, artists and intellectuals? Didn’t the public-private partnerships promoted by the CHP allow for the emergence of an affluent class of Turks in those years? The CHP did what was in the ‘national interest’ back then. The AK Party is doing what is in the ‘national interest’ now.

As I wrote my preface, I saw clearly how, when it comes to power politics, the distinction between Islamist and Republican doesn’t apply: both are obsessed with power. The CHP built a regime of capital accumulation in the 1920s, filling the coffers of the young Republic with the confiscated properties, businesses and savings of the Greeks and Armenians who had formerly inhabited Istanbul and Anatolia. The party first purged academia in 1933 under the pretence of a ‘university reform’. Darülfünun, Turkey’s sole autonomous modern academic institution during Ottoman rule, was cleansed of critics of Kemalism.

The second purge was carried out by the CHP in 1948 after Turkey’s realignment with the western bloc, following the regime’s brief flirtation with Hitler’s Third Reich. Carrying elements of McCarthyism, the purge targeted alleged communists employed at Ankara University’s Faculty of Language, History and Geography. In the aftermath of the 1960 military coup, a third purge led to the firing of 147 scholars, including some of the most talented literary minds of their time: Mîna Urgan, Sabahattin Eyüboğlu and Orhan Duru. Three years after the 1980 coup, the dictator Kenan Evren used Martial Law act 1402 to dismiss 117 scholars. As a teenager in the early 1990s interested in leftist literary and political cultures, these persecuted academics were my heroes.

Erdoğan was aware of this history when, in 2016, he targeted Academics for Peace, a group of over 1000 scholars who had signed a declaration calling for a ceasefire between Kurdish militants and the Turkish state. Directing his ire at intellectuals, Erdoğan morphed into a Kenan Evren figure before our eyes, branding the country’s leading professors traitors and terrorists. Six hundred signatories were charged under the anti-terror law; thirty-six scholars were handed prison sentences between 15 months and three years.

In 1933 and 1948, the CHP saw free-minded citizens as a threat to its vision of enforced modernization. The generals did the same in the aftermath of the coups in 1960, 1971 and 1980. In demonizing critics of the Erdoğan regime as impediments to Turkey’s progress, the AK Party is now re-enacting this legacy. In all these instances, what the Turkish courts punished is any reckoning with the foundations of the Turkish state. They continue to silence those they deem too loud. After all, speaking a lot is perceived as a female quality. For those in power it can be annoying, even threatening.

What does Turkey’s mainstream opposition have to say about that? Very little, I’m afraid. Over the past year, Kılıçdaroğlu has been proposing a process of helalleşme (reconciliation) with the various sectors of society that his party, the CHP, have excluded in the past in the name of the national interest. The process goes like this: you, the perpetrator, ask for the good wishes of the injured party, and the injured party gives it to you out of goodness.

Meanwhile, a slightly different concept, helallik (giving a blessing), has become a crucial element of Erdoğan’s rhetoric. After the disastrous response of his regime to the lethal earthquakes in February, the strongman asked for helallik from survivors. His administration had done all it could, the president claimed; the rest could be blamed on fate. Now he was asking for helallik and, of course, votes. Neither helalleşme nor helallik promise reparations or meaningful changes. They’re just words.

No wonder people didn’t believe Kılıçdaroğlu. His words were seen as fluff – window dressing meant to hide the CHP’s anti-democratic history. There is an irony in Turkish liberals placing their belief in such rhetoric. When defending Erdoğan during the first decade of AK Party rule, Turkish liberals made a similar mistake. Despite warnings from leftists that in claiming to uphold European values, Erdoğan was in fact practicing taqiya (an Islamic term meaning to resort to sinful acts for pious goals), liberals insisted on taking the Islamists at their word. The AKP’s promise to wed piety with liberal democracy and free-market capitalism held an allure too strong to resist.

The resentment held by CHP supporters towards liberal reforms introduced by the AK Party during its first decade continues to this day. Between 2002 and 2012, the Turkish parliament passed a flurry of laws that rolled back many of the discriminatory and racist policies of the Turkish republic, halting states of emergency in Kurdish cities, lifting bans on the Kurdish language, acknowledging atrocities committed in the eastern Anatolian city of Dersim in 1938, abolishing the student oath that forced all children, irrespective of their ethnicity, to shout ‘I’m a Turk!’ at school ceremonies, and raising prospects of an open discussion about the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

Statue of Kemal Atatürk. Image via Unsplash.

In response, the CHP charged politicians and intellectuals like the late poet Roni Margulies with betraying Atatürk’s legacy. During the election season, Kılıçdaroğlu regularly talked about prosecuting Erdoğan for crimes against the republic, his tone switching from mellow liberal to fiery nationalist in a matter of seconds. After the death of Margulies, Turkey’s Kemalists wrote unforgiving obituaries of my departed Marxist friend. Their lexicon of betrayal to the republic and punishment of traitors attest to their affinities with Erdoğan.

*

In the weeks following the election, I followed the news about the internal strife plaguing the CHP. In a leaked Zoom call, a group of high-ranking members debated taking down Kılıçdaroğlu. A younger, more charismatic male figure from the CHP ranks is expected to replace him. The obsession with power continues, now in the more contained context of party administration. Last spring, all that opposition figures could talk about was power sharing, hoping to win voters through a process of horse-trading over key ministries in an imaginary cabinet. At the time, these men (and they’re all men) resembled boys playing with toy soldiers. In their fight to lead the CHP, they still do.

While in-party fighting continues to occupy the opposition, the government’s assault on the LGBTQI community grows exponentially. Dozens of LGBTQI activists were detained during this year’s Pride month. Elyas Torabibaeskendari, an Iranian refugee, was taken into custody during the Pride March in Istanbul and sent to a repatriation centre in Urfa. Despite being released after a month in detention, he still faces deportation to Iran, where he faces torture or worse. In July, a female student holding a rainbow flag during her graduation ceremony at Uşak University was accused of holding a ‘piece of trash’, an expression used by ultra-nationalists to describe flags of illegal terror groups. Instead of condemning the attacks, the university opened an investigation against her. Increasingly, queerness is becoming the focus of all that the Turkish state hates and wants to punish.

It’s no wonder that the mainstream opposition does not speak out. Interested only in replacing Erdoğan, they’re terrified of being seen as weak, degenerate or deviant. They want to represent the norm, and the normative identity they champion is the one propounded in the 1920s: that of the secular, heterosexual, hardworking citizen who devotes their life to the Republic. Yet normativism is a battle the opposition can’t win. Erdoğan has already branded his rivals as ‘LGBTQI lovers’. His government considers anyone opposing its patriarchalism, exploitative capitalism and resentment of ‘the other’, as weak, soft and worthy of extermination. Speaking immediately after his victory, Erdoğan emphasized that ‘deviants’ would never sneak into the AK Party ranks.

This obsession with power, virility, and the nation’s sexual and territorial ‘health’ go hand in hand with the assault on LGBTQI rights. Turkey’s mainstream opposition parties can’t raise their voice against the assault on weakness. In their obsession with power, they drink from the same poisoned well. No wonder they reproduce a similarly exclusionary ideology that accuses its opponents of ‘betraying Turkey’.

*

I’ve long believed that the only way to lead an ethical life in Turkey is by joining the ranks of the ‘deviants’. After all, the political organizations that truly counter the repressive nature of the Turkish state have all been pushed to the margins. Selahattin Demirtaş, the former co-chair of the progressive HDP, has been behind bars since 2016 and is facing multiple life sentences. Osman Kavala, an arts patron who devoted his life to commissioning literary and artistic work probing Turkish autocracy, has been in jail since 2017. He has been punished with the same severity as murderers. These figures, alongside a small set of progressive NGOs and marginalized political parties, continue to uphold democratic values.

From the non-profit cultural institution Anadolu Kültür, which turned twenty last year, to the Citizens’ Assembly, founded in 1990 as the Turkish branch of the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly; from the Turkish LGBTQI organizations Lambda Istanbul (founded in 1993) and Kaos Gay and Lesbian Cultural Research and Solidarity Association (founded in 1994), to the Human Rights Association (founded in 1986) – the political organizations we trust have been consistent in their defence of democratic values. We take the spokespersons of these organizations at their word: they’re obsessed with ethics and political principles. None of them have been poisoned by power. Their lexicons feature rights and freedoms, in place of concepts like helallik or helalleşme.

When I interviewed him in April, Selahattin Demirtaş told me something that has remained with me. ‘My experience has shown me that without considering the issue of gender and without asking for equity in gender politics, there is no chance of cutting the ties between authority, power and hierarchy.’ In blinding clarity and from inside his prison cell, the Kurdish politician – rarely a pessimist and often a cautious optimist about prospects of democratic change – had diagnosed Turkey’s disease.