Belarus and its people are currently navigating complex processes of democratization. From clashes on the streets to intellectual discourse on political rhetoric and media representation, the official line on Belarusian identity comes under scrutiny.

In the following interview, the Belarusian online magazine CityDog.by asks author Nelly Bekus about her book on Belarusian identity and current research on clothing as cultural and social identity markers:

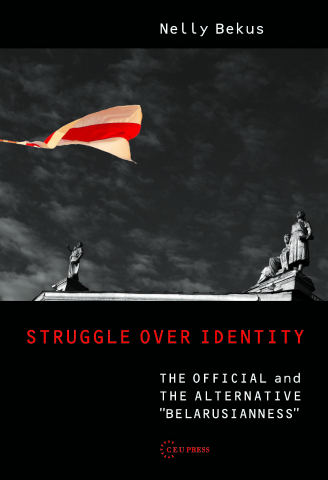

CityDog.by: The well-known Ukrainian political analyst Mykola Riabchuk wrote that your book Struggle Over Identity, in which ‘Belarusianness’ was broken down into an official and an alternative identity, was in fact about two Belaruses. What did he mean?

Nelly Bekus: Mykola Riabchuk is the author of a book about ‘two Ukraines’, which came out long before my own. It is possible that he saw my book through the prism of ideas about his own country. This is where the thesis about two countries comes from.

Society in Belarus is significantly more homogenous than in Ukraine, where certain regions were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire but never part of the Russian Empire. They also existed in a space characterized by different national, religious and linguistic policies. By virtue of their different historical experiences, the national consciousness of Ukrainians living in the western regions strongly differs from the consciousness of those living in central and eastern Ukraine.

As for my book, I do not think that people are divided by national identity. Every ideology, including national ideology, is a set of discourses, institutions and practices. For this reason, there is no idea of ‘two Belaruses’. We live in a single society. In this sense, it was important for me to demonstrate that people are not divided into various groups from the start but that the struggle takes place on the level of political rhetoric, and certain educational and cultural practices, as well as mass media policies. These are the things that shape segments of society, which cannot thereafter come to terms with one another.

The official ‘Belarusianness’ and the alternative ‘Belarusianness’ are two different sets of ideas about what Belarus is and what lies at the heart of its identity. In my book, I give a broad overview of the various interpretations of Belarusian history – how they are presented in textbooks, alternative sources and by independent historians. I analysed political discourses, the media sphere and how the mass media constructs ideas about Belarusianness.

A separate chapter was devoted to the latter and it became my entire project. I applied for a Milena Jesenská Fellowship at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna on this basis.

I was in Vienna for three months and wrote several articles, including ‘An Invisible Wall’, which analyses why Belarusian society is divided and why it is so difficult for people with different convictions to find a common language. I argued that a key explanation lies in how people work with and interpret information, and what sources they use. When I was working on the article, which later became ‘Belarusian-Specific Nature of the Public Sphere’, a chapter in my book, it seemed that society divided according to how people consume information was some kind of distinguishing feature of Belarus.

Following my fellowship, however, I have lived in several countries and have become convinced that this is not actually the case. There are similar ‘invisible walls’ dividing supporters and opponents of Brexit, Trump in America and the ruling ‘Law and Justice’ Party in Poland.

CityDog.by: What is specific to the situation in Belarus? Can you discuss the official and alternative notions of ‘Belarusianness’ that you write about in your book?

Nelly Bekus: Over the relatively brief history of Belarusian independence, ideas of what constitute the core of Belarusianness and Belarusian identity have become highly significant.

One of the key pillars of the official version of Belarusian history is its significant emphasis on those aspects of tradition that shaped both Belarusian and Russian existence within a single state. Whether it was the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union, these periods of common existence are understood as the key factor shaping Belarusian identity.

In the alternative interpretation of history, Belarusians are seen as an Eastern European nation that has more in common with Poland, Lithuania and Czechia. In this context, the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Commonwealth of Poland become significant in the creation of Belarusian traditions and the foundational elements of Belarusian identity. During these historical periods, Belarusians had more in common with Poles and Lithuanians than with Russians, which underscores that Belarusians are a European people and nation, one with a European history.

Numerous ‘markers’ of identity – the roles of the Belarusian and Russian languages, Orthodox religion, collective memory – are understood differently in the diverging contexts created by political rhetoric. For example, the memory of the Second World War or the Great Patriotic War occupies a central place within official memory politics. The Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War reflects this ideology and its place in the urban space of Minsk is an eloquent illustration of the point. On the other hand, within the alternative (opposition) idea of Belarusianness, the memory of the victims of Stalin’s repressions is central.

In the alternative vision of Belarusianness, Kurapaty [a forested area on the outskirts of Minsk where several thousand people, mainly Belarusians, were killed between 1937 and 1941 by the Soviet secret police] plays an analogous role as a ‘key site of memory’, a symbolic space commemorating the Belarusians who fell victim to Soviet crimes. Its significance lies in the fact that it ought to help society not only recognize the criminal character of Stalinist repressions but also demonstrate the foreignness of Soviet rule to Belarusians in general.

At the same time, at least for the official idea of Belarusianness, the Soviet period saw the establishment of the Belarusian nation, post-war modernization and urbanization, and the expansion of industry – in short, everything for which Belarus became known in the second half of the twentieth century.

It is worth noting that the idea of nations as victims of communist regimes is at the centre of collective memory and has become a characteristic feature of Eastern European national discourses, one that appeared after the collapse of the Soviet Union. At the same time, the attempt to form an image of Belarusian identity along the same lines as other Eastern European nations reinforces the idea that Belarusians do not differ in any way from their neighbours. They are the same as Poles, Lithuanians and Czechs.

One of the paradoxes of the struggle between official and alternative identities was and remains the fact that it does not take into account the role of society, of the people depicted by these national ideologies. Society was supposed to be a passive recipient, accepting an image of itself from one side or other of the barricades and then live up to it.

Detail of motherland monument, Museum of the Great Patriotic War, Minsk, Belarus. Photo by Adam Jones, Kelowna, BC, Canada, via Wikimedia Commons.

CityDog.by: How have ideas about Belarusianness and the identity of Belarusians changed after the election?

Nelly Bekus: What has been happening in Belarus since the summer of 2020 is not only the unexpected mobilization of society against falsified elections and violent repression (unexpected both on the part of the authorities as well as the ‘old opposition’, i.e., those who opposed Lukashenka all these years). Even more so – and this may be its primary meaning – it has also been the sudden shift from subject to protagonist, when Belarusian society declared that it has the power to define its own future. The falsified election, in fact, is primarily a demonstrative removal of the right to have one’s voice taken into account.

The protests have created an incredibly important new space in which ideas about Belarusianness are re-conceptualized and given new meaning. This revolution in the reconfiguration of the symbols of cultural identity is, in my view, no less momentous than changes in the political system and the democratization of power.

One of the most symbolic pictures, which is probably familiar to everyone who has been following events in Belarus, is a photo from 16 August, when protesters surrounded the Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War and wrapped the ‘Motherland’ monument in the white-red-white flag (long the symbol of the Belarusian opposition), demonstrating both the incredibly broad mobilization of society during the protests, and the ongoing transformation of cultural symbols and historical ideas that form Belarusians’ collective memory.

The Museum as a symbol of the ‘glorious Soviet past’ and the flag as a symbol of anti-Soviet resistance – two symbols that had been closely associated with mutually hostile, ‘ideological’ Belarusian national projects – were united in the representations of the new Belarus that appeared during the protests. The event shifted the meaning of these symbols, endowing protesters with some of the location’s pathos (near the Minsk Hero City Obelisk) and giving the struggle against the Lukashenka regime a heroic aura.

The image of the ‘victorious people’ of the Second World War (promoted by the official ideology and memory policy of the state) has taken on new meaning. In general, the abundance of references to the Great Patriotic War in the Belarusian protests is striking, from the comparisons to violence suffered by Belarusians under German occupation and the experience of partisan warfare – both of which help Belarusians today persevere in the face of repression and lack of freedom – to the works of Belarusian artists Viktoria Zhukovskaia and Anna Redko, which make use of the ‘Motherland’ monument.

Because they reference historical experiences, all of these historical images have become an important symbolic toolkit that can be used to depict protesters heroically, strengthening feelings of solidarity in society. Paradoxically, it is those elements of historical memory that are at the centre of official Belarusian ideology and identity, which are now being used for mobilizing the people against the very regime that had itself inculcated this ideology.

At the same time, ideas that formed the core of the alternative notion of Belarusianness (the image of Soviet regime victims, for example), have also taken on broader resonance due to the protests. One need only recall the ‘Chain of Repentance’ from Kurapaty to Akrestsina, the ‘Night of Executed Poets’ in Kurapaty or the Dziady requiem march on 1 November. These examples not only create associations between today’s repressions and those of the Stalinist terror but also drew large numbers of people to memorial sites for victims of repression, people who may have never previously participated in the memory work of the political opposition. The fact that people from various social groups joined the protests led to the creation of a space for improvisation and the reconfiguration of cultural and political symbols.

It turns out that, in the process of this mobilization, society not only entered the political arena but also began to participate in a re-working of its identity. Ideas about Belarusian identity, which had earlier formed the basis for two competing [political] projects and ideologies (both official and alternative), were combined in new ways and changed meaning.

While we still await this revolution’s conclusion, there is no doubt about what it has already accomplished: the effacing of that fierce stand-off that had divided the cultural and political landscape of Belarusian identity. The heroic image of protesters, the experience of lived trauma, the memory of victims – all of these are included in the new image of Belarusian identity.

CityDog.by: In Vienna, you were working on a small research project about how clothing ‘allows you to communicate your message to society and to display your identity’. You also wrote that, in principle, Belarusians’ external appearance can serve as a comment on how public space in the country is organized and how individuals structure their relationship with the world around them. Is this still the case?

Nelly Bekus: Without a doubt. At that time, of course, the research was based on my reaction to how differently people in Belarus dressed in comparison to other countries where I had lived (mostly in the late 1990s and the early 2000s). Having lived in Warsaw and Vienna and having spent a few months in America before Austria (returning each time to Belarus), I kept thinking that things had changed on our streets. People had a different attitude to their surroundings and to how they looked when in public.

Convenience and comfort in fashion had become widespread at the time among young people in Poland and Austria. The philosophy of clothing in everyday life involved a natural external appearance and the minimal use of cosmetics. This phenomenon can be considered a form of freedom from the expectations and ideas about how women, primarily, ought to appear in public.

In the Western world, public spaces are differentiated: how a person ought to appear at the theatre or a restaurant is quite different from how they should look when going to the post office or the park. In the former, one’s appearance predictably reflects the specificity of the atmosphere and, as a result, requires a specific appearance and style in the choice of clothing; in the case of the latter, one can simply be oneself.

In Belarus, as it seemed to me at the time, the space in which one could be oneself and not be overly concerned with one’s appearance was quite narrow for many women. This is the fundamental difference between ‘being an object of someone’s expectations of an “appropriate” appearance’ and ‘being the subject in one’s own choice’. One can say that society creates a certain set of expectations and many women strive to meet them. Of course, this theme obviously touches on deeper questions of tradition and the power of stereotypes along with the role of clothing as an instrument of social and gender control.

Now, I think, the situation in Belarus has changed. Things are changing in the rest of the world too. We may see that, after the removal of all the pandemic-related restrictions, people will start to relate to public spaces in new ways and structure their relationship to them differently, including through the use of clothing.

This interview was first published in CityDog.by

Published 16 February 2021

Original in Russian

Translated by

Markian Dobczansky

First published by CityDog.by (Russian version) / Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Institute for Human Sciences © Nelly Bekus / CityDog.by / Institute for Human Sciences / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

On the border between Poland and Belarus, the Forest has become the subject of a humanitarian crisis. An artist’s report, based on meetings with activists and refugees, charts this contested space. Poetry honours those lost in transit.

Political failures after independence allowed Belarusian society to become captive to the pro-Russian state. As Lukashenka enters his seventh term, five years after crushing the peaceful revolution, what lessons can the opposition take?