Bankrupt

Wespennest 189 (2025)

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Literature can’t save the world, but it does provide insight into the behaviour that drives cultural trends. And given the anthropocenic tendency towards self-destruction, we need all the help we can get with cultivating solidarity, combating injustice and resisting censorship.

‘He clung absurdly to the idea’, as do I, that societal cohesion isn’t breaking down. Julio Cortázar’s short story The Southern Thruway came rushing to mind when I read Martin Vrba’s writing on the ecological class. Certain stories, like old friends, are reliable, interpretative, candid. Conveyed in under thirty pages, Cortázar’s expansive narrative from 1966 about the tribulations of surviving in times of dire need persists. Living, loving, battling and dying in a motorway traffic jam outside Paris over months on end, until the impasse eventually breaks, provokes thoughts about the expediency of solidarity.

Vrba refers to Latour and Schultz’s theory of a global ecological class united through environmental struggle and social conflict. ‘Solidarity …’, he writes, ‘is an underlying social bond that is invisible in everyday life and can temporarily manifest itself … during emergencies.’ Cortázar’s characters, arbitrarily connected by the position of their slowly advancing cars, soon pool their resources and face adversity together. The story takes an everyday industrialized-world disruption – the traffic jam – to extraordinary, dramatic extremes: hunger, thirst and harsh weather collectivize people, but supply missions into the surrounding countryside incur a backlash of violence and a black market emerges. In the short story, as in life, when confronting emergency, there are those with and those without, and those who profit from misfortune.

Jan Patočka’s ‘solidarity of the shaken’ informs Vrba’s understanding of what might bond the emerging ecological class: ‘While usual solidarity is based on common ground, … the solidarity of the shaken stems from the experience of the complete loss of ground, an existential groundlessness caused by frontline experience. … Patočka is convinced that only the destruction of all false, socially given meanings can lead to a new, authentic meaning.’ It’s an interesting point that counters tendencies to turn a blind eye to the climate crisis – the inherent denial while focusing on self-care at best, carrying on with ‘life as normal’, or blatantly exacerbating emissions at worst.

Cortázar’s version of ‘shaken-ness’ provides a cautionary tale: ‘the idea of a natural catastrophe spread all the way to the engineer, who shrugged without a comment’; after many ventured hypothesise, ‘Peugeot 404’, the story’s main character, disengages from yet more news of the emergency’s origin. But he isn’t callous; he contributes strategically, his car becomes the local ambulance and he falls in love with ‘Dauphine’, the young female driver from a neighbouring lane. Rather Peugeot 404 is cynical, ‘sure that almost everything was false’.

The character accepts Patočka’s ‘groundlessness’, briefly glimpsing ‘authentic meaning’ in shared experience and symbols of freedom: ‘a big white butterfly’ lands ‘on the Dauphine’s windshield, and the girl and the engineer admired its wings, spread in brief and perfect suspension while it rested; then with acute nostalgia, they watched it fly away’.

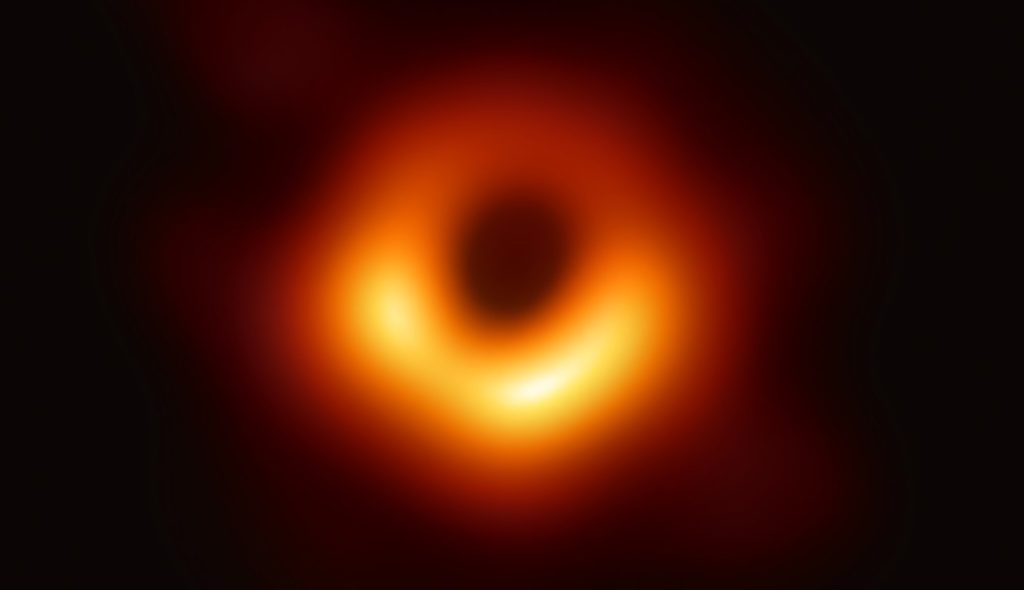

The Event Horizon Telescope’s image of a black hole. Image via Wikimedia Commons

But adequate responses to the climate crisis require more than wistful thinking. ‘In our time, such environmental metanoia – a radical change in one’s life based on the experience of virtually losing the ground under our feet – stems from an awareness of life and death on a large scale,’ writes Vrba. ‘It becomes a shared experience of loss, after which we find ourselves unable to live our lives the same way as before.’

We have recently experienced loss through a global, life-changing emergency. But many since recognize that it only temporarily altered our behaviour. Reduced human activity during the COVID pandemic – which has become such a pariah of an example that I hesitated to include it here – had an evidently positive environmental effect. But the simultaneous psychologically negative effect of freedom being restricted led to a consequent rejection of any lasting slowdown. Vrba who steers clear of the pandemic suggests the need to heed such warnings nonetheless: ‘if no change has occurred in our lives after we have confronted the climatic and environmental predicament facing us, we still don’t understand the magnitude and gravity of what is really happening.’

Peugeot 404 laments the loss of routine care, responsibility and simple pleasures, when ‘at nine-thirty the food would be distributed and the sick would have to be visited, the situation would have to be examined with Taunus and the farmer in the Ariane; then it would be night. Dauphine sneaking into his car, stars or clouds, life.’ But he also dreams of personal gratification, civilized indulgences: ‘Paris was a toilet and two sheets and hot water running down his chest and legs, and a nail clipper, and white wine, they would drink white wine before kissing and smell each other’s lavender water and cologne before really making love with the lights on …’

Does the engineer’s fantasy become a reality? SPOILER ALERT: As the traffic jam begins to ease, Peugeot 404 loses sight of Dauphine. All that remains is moving ‘towards the lights that kept growing, not knowing why all this hurry, why this mad race in the night among unknown cars, where no one knew anything about the others, where everyone looked straight ahead, only ahead.’ Once the cars are moving freely again, all that held the impromptu community together dissipates – as if it also never existed. Only the vehicles carry on, in their isolation.

Vrba is searching for a means to slam on the brakes: ‘Inevitably, the solidarity of the shaken is a rupture with the social order. All normality is suddenly seen as madness; what has been considered healthy is sickening. Rooted in collectively shared shaken-ness, it offers an opportunity to be unified by a common purpose that transcends mere individual interest.’ The question of how to mutually take the foot off the gas, however, remains.

The ‘frontline experience’ applied to environmental disaster is, of course, also currently a wartime reality for many. The ground is being shaken in Gaza, in Syria, in Sudan, in Ukraine. Yevhen Shybalov, once a pacifist who took up arms when Russia started its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, offers a personal account of the reasons why a humanist would kill.

Shybalov spent many years from 2014 ‘providing humanitarian aid to civilian war victims in Ukraine’s east’. When he joined the military in 2022, many of the foreigners he had met through his work ‘were genuinely surprised when this peacemaker suddenly became a soldier,’ he writes. But Shybalov himself is astounded by the collective decision instead: ‘Why am I not alone? Why are there so many of us?’ Like Shybalov, ‘civic activists, human rights advocates, altruists, artists, writers, scholars’ all signed up. And with the directness of someone who has irrevocably stepped over a personal line, Shybalov answers: ‘The secret is simple. We are the same kind of people as everybody else. But shameless, unrestrained injustice makes us go berserk.’

That Ukraine has a frontline rests with Russia, where internal oppression is also rife. But hardly any detail of the negative impact on everyday Russian lives surfaces. Miron Samokov, Svetlana Sinitsa, Natalia Baranova and Violetta Grishkova’s overview of the Russian State Duma’s plans to ban books by ‘foreign agents’ from libraries makes for intriguing reading.

While library management tends to ‘play it safe’, removing listed books ahead of the ruling, some librarians are doing what they can to resist. The ubiquitous ex-library books in many private, home collections will soon be more than a slight indiscretion in Russia: ‘some staff take them home, and sometimes readers steal books by foreign agents. They borrow them on their cards and then never return them,’ one librarian reveals.

Literary censorship isn’t new in Russia, but whereas books were once burned, they are now being recycled – at least one advance, even if perverted, has slipped past the Kremlin’s retrograde actions. And censorship can always have the opposite effect, as another librarian confides: ‘People joke that being labelled a foreign agent is the best recommendation.’

Published 28 November 2024

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Parables of violence; memories of dictatorship; perversions of memory: Ord&Bild samples contemporary Latin American literature and photography.