Outer Space, the next Wild West

COP26’s mandate focuses on averting the loss and damage caused by climate change. And technological solutions hold much promise. But high-tech and the environment aren’t always best matched: largely unregulated mega satellite projects are on the increase with space debris a real near-space threat.

Space debris is currently growing rapidly, because of the expanding number of satellites circulating in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), designed to increase global Internet coverage and provide earth observation data. LEO satellites are now being launched in mega-constellations, vast clusters of satellites that number in the thousands. These satellites typically have a short lifespan, lasting no more than a couple of years. The defunct satellites then add to the growing number of debris objects. Collisions at orbital velocities can be dangerous, even deadly.

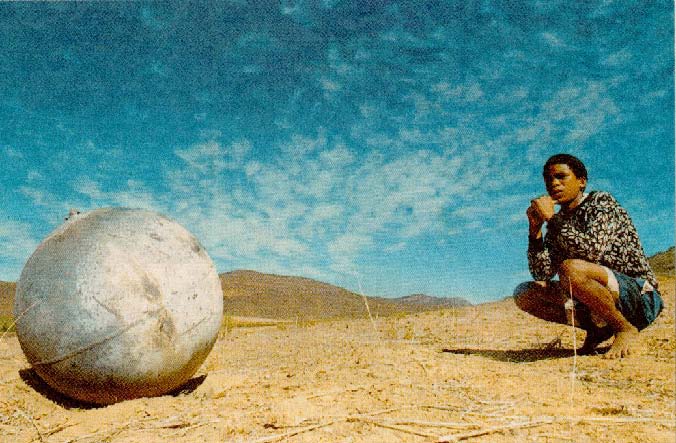

Human-made pressurization sphere stemming from a rocket body that fell in Southern Africa. Image courtesy of NASA, Wikimedia Commons

To better appreciate the scale of things to come, let us consider the case of Starlink, the mega-constellation currently being launched in batches by billionaire Elon Musk’s company SpaceX. The intended size of this LEO constellation is 42,000 spacecraft (a figure based on current frequency spectrum filings with the US Federal Communications Commission).

Another issue of concern with mega-constellations like Starlink is that they represent a takeover of a shared public resource – outer space – that has all the hallmarks of a landgrab by private enterprise. In the absence of farsighted and enforceable space laws, the takeover of LEO will become a fait accompli, as thousands of satellites take to the skies without regulatory oversight or environment-friendly space laws. Furthermore, such networks, comprising thousands of shiny objects, also interfere with ground-based astronomy.

Space debris can be anything from defunct satellites to small shards of solar panels and rocket pieces. Here are the latest figures related to space debris, provided by the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office at the European Space Operations Centre, Darmstadt, Germany.

In summary, there are nearly 34,000 objects made by humans that are larger than 10cm, 900,000 objects in the 1-10cm range, and 128 million objects in the 1mm-1cm range. Such extreme satellite and debris traffic could eventually lead to a catastrophe on a scale similar to what we have now started to witness with the domino effect of anthropogenic climate collapse.

Outer Space, humanity’s shared resource, is fast turning into the next Wild West. The twenty-first century, unlike the twentieth, will not see a race between nations, but rather a race between private companies – to exploit space assets, mine space resources and ferry tourists.

In the absence of binding international treaties, unilateral and unfettered commercial exploitation of outer space resources is almost certain to happen. Thus, for example, in 2015, during the Obama administration, the US Congress passed legislation that unilaterally gives American companies the rights to own and sell the natural resources they mine from bodies in space, including asteroids. In 2017, the Luxembourg parliament voted in favour of an asteroid mining law, similar to the American one, that gives Luxembourg-based mining companies the right to keep their loot. In 2017, commercial companies, governments and amateurs launched more than 400 satellites into orbit, over four times the yearly average for 2000-2010. In 2018, Elon Musk tossed up a red roadster into space. Some consider this a nerdbaiting publicity stunt, others an obscene act of megalomania. Either way, it sets a worrisome precedent for the mindless littering of outer space with personal effects.

A prototype Arctic Weather Mission satellite. Image courtesy of European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

In March 2019, India’s Prime Minister Modi ordered India’s first demonstration of anti-satellite technology (ASAT) – space weapons technology designed to target the satellites of opponents. This raised further debris concerns for the crewed orbiting International Space Station. In so doing India was joining a club whose previous members were the US, Russia and China: others are bound to follow. Later that year, in October 2019, Richard Branson’s company Virgin Galactic went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk also have plans to ferry paying tourists into space. SpaceX is flying Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa to the International Space Station in December 2021, and in June 2021 Bezos revealed his plans to fly with three others, on 20 July, on the first crewed flight of the New Shepard suborbital vehicle built by his company Blue Origin. The Bezos announcement was followed by one from Branson that he would beat Bezos by a week.5 Casual passenger spaceflight is about to take off. This will add to LEO environmental woes.

This kind of behaviour – by individuals, companies and governments – is in the classic tradition of the ‘he who dares wins’/‘he who has the money can get away with murder’ philosophy of the Wild West. Altruistic principles that treat space as a shared resource, as found in the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and the Moon Agreement of 1979, have been rendered obsolete.

The question we, as humanity, need to be asking ourselves is how we managed to get into the situation of being completely unprepared, legally speaking, to deal with this level of irresponsible conduct, environmental apathy and unethical business practices. One part of the answer lies in the inadequacies of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which forms the basis of international space law and governance. That treaty was a product of its time: it was designed to de-escalate cold war tensions and prevent the nuclearisation of space. At the time it was drawn up the idea of privatising space was nowhere on the horizon.

It is time, now, not just to upgrade the Outer Space Treaty, but to completely overhaul it. Any new treaty will need to find solutions that comprehensively address the presently unconstrained operation of human greed and expansionist tendencies to mine-monetise-colonise whatever is encountered in space. Twenty first century space governance needs farsighted and enforceable laws, traditional wisdom, planetary ethics, and real-time and reliable data about orbital traffic, if we are to ensure the safety, security and sustainability of space operations in the face of the growing number of space actors, space objects, space debris and adverse space weather phenomena.

We are in a state of planetary emergency, both on and off the planet.

This article first appeared in Soundings 78/2021.

The main task of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPOUS) is to review and foster international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space, as well as to consider legal issues arising from the exploration of outer space. It was created nearly sixty years ago, in December 1959, and has grown over the years to include 95 member nations. With such a large number of countries, however, it is nearly impossible to come to a consensus on new laws that can comprehensively address the challenges we now face. This raises the question of how the world will cope with the accelerated environmental degradation and occupation of near-earth space.

It is my belief that the COP forum should therefore stretch its imagination to include the near-earth environment of LEO within its concept of the earth’s climate, in order to highlight the environmental threat posed by the rise of megaconstellations. The conference could provide the opportunity to acknowledge, as a collective, the growing menace of human-made debris in near-earth space, and call for the world’s nations to unite to pass a new declaration on LEO.

Published 2 November 2021

Original in English

First published by Soundings 78/2021

Contributed by Soundings © Susmita Mohanty / Soundings / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Europe produces 5 tons of waste per capita each year and exports a significant portion of it for other countries to handle. Can we reduce, reuse, and recycle our way out of this? New talk show episode premiers today.

Mineral rush

Topical: Critical raw materials

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.