Bankrupt

Wespennest 189 (2025)

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey has returned to its ‘normal’ state of emergency, in which freedom of speech is punished and where minorities bear the brunt. Armenian journalist and publisher Rober Koptaş looks to persecuted writers of the past for examples of strength and resistance.

He put the sack on the ground and opened up a one-metre by one-metre folding stall. On the leather surface he started to lay out his stock, which he left in the evenings with a soldier friend working as an office boy in Büyük Yeni Han and picked up again in the mornings.

From the sack first came drawers, then bras – classic ones laid out separately from the American products with the new style of plastic whalebone – and then a few corsets and nightgowns placed on top of each other on the left. He folded up the sack and stuffed it among the wires underneath the low bench on which he would rest when tired.

That was it. That was his preparation completed. Now all he had to do was wait until evening, shout to draw in customers when the area filled up a little, order some linden tea from the tea-maker in Çakmakçılar Han if he got cold, and pray to the God he does not believe in that no one he knows from Kadıkoy shows up.

Probably the best comparison to Zaven Biberyan’s shout of ‘Underwear for the ladies! Drawers! Bras! For the ladies…’ is Züğürt Ağa, the leading character in the 1985 film of the same name (English title: The Broken Landlord), who is reduced to roaming the streets of Istanbul calling ‘Tomatoes! Tomatoes!’ in an embarrassed voice that is only audible through a loudspeaker. ‘Tomatoes! Tomatoes!’ ‘Underwear for the ladies! Drawers!’ ‘Tomatoes…’

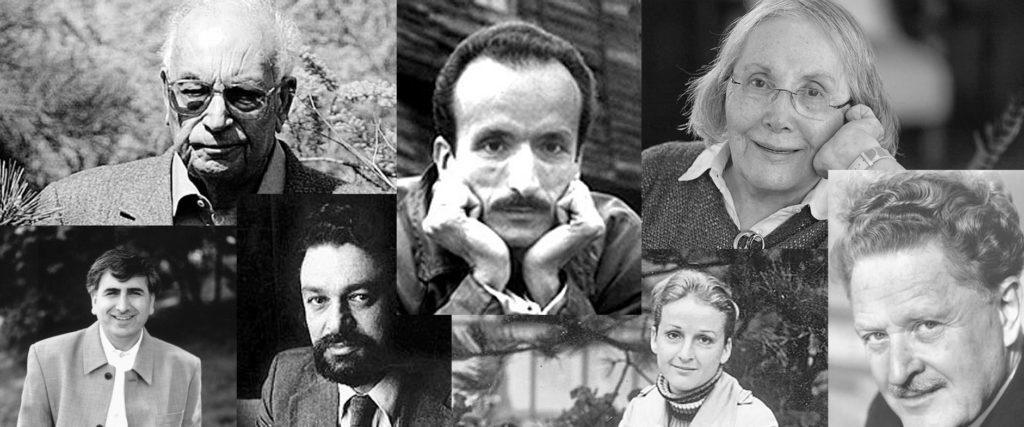

From left to right: Mehmet Uzun, Yaşar Kemal, Oğuz Atay, Zaven Biberyan, Sevgi Soysal, Adalet Ağaoğlu, Nâzım Hikmet.

The same Zaven Biberyan, a few years later, would write Mırçünneru Verçaluysı (‘Sunset of the Ants’, translated from Armenian into Turkish as Babam Aşkale’ye Gitmedi (My Father Did Not Go To Aşkale). Now accepted as one of the greatest novels written in Armenian, it took until the 2000s for Biberyan’s work to find favour and be debated by critics.

In December 1946, the martial law authority closed the Armenian newspaper Nor Or (New Day), which Biberyan and a group of colleagues launched just thirteen months earlier, along with Turkish newspapers published in Istanbul such as Ses (Voice), Gün (Day), Yığın (Mass), Dost (Friend) and all active labour unions. Avedis Aliksanyan, Aram Pehlivanyan, Zaven Biberyan, Vartan İhmalyan, Jak İhmalyan, Barkev Şamikyan and Hayk Açıkgöz, who were among Nor Or’s managers, writers and cartoonists, were arrested and thrown in jail. All were linked to the Turkish left and to the underground TKP (the Communist Party of Turkey), the movement’s sole representative. The transition to a multi-party system, the establishment of unions and associations and the publication of dissident periodicals, was still relatively new in the wake of World War II. This atmosphere of relative freedom that succeeded the one-party millstone enlivened not only politics, but also cultural life, as seen in the permission given for the first time in Republican history to Armenian theatre performances.

This breath of fresh air was not to last long. Turkey’s leading intellectuals, among them Biberyan and his friends around Nor Or, who were the first since the 1920s to try to raise their voice as the Armenians of Turkey, ended up in prison. Some had been crushed a few years earlier by the Wealth Tax1 aimed at non-Muslims, and by racist policies such as ‘The Twenty Classes of Public Work Military Service’.2 Before they could fully recover, they had been tortured in the cells of the Sanasaryan Building in Sirkeci, property that was seized from Armenians and used in that period by National Police as a ‘political crimes branch’. The Sanasaryan Building, more often known in leftist literature as the ‘Sansaryan’, was the place at that time and later where many were imprisoned and tortured, among them Vedat Türkali, Ece Ayhan, Aziz Nesin, Attilâ İlhan, Mihri Belli, Ahmed Arif, İlhan Selçuk ve Ruhi Su.3

As Armenians whose life chances in Turkey had been wholly restricted by jail or prosecution, Aram Pehlivanyan, the İhmalyan brothers, Keğam Sevan, Sarkis Keçyan Zanku, Avedis Aliksanyan, Yetvart Ağamyan, Haçik Amiryan4 were forced to migrate abroad, to Aleppo, Beirut, Paris, Moscow and Yerevan. None of them would ever return. Like their friend Nâzım Hikmet5 they departed from this world still longing for Istanbul.

Zaven Biberyan was also forced to move abroad. He worked in Beirut on the Armenian newspaper Zartonk (Awakening). But in 1953, as the atmosphere calmed a little, he would return to Turkey. The Pogrom of 6–7 September 1955 would soon follow, proving that the atmosphere was not that calm. Tough times returned again after Turkey’s first coup on 27 May 1960. Because of his politics, Biberyan became unemployable at Armenian newspapers such as Marmara and Jamanak (Time). And so began the days of selling women’s underwear in Mahmutpaşa. He had no other way to earn a living.

Despite these adversities, Zavan Biberyan never severed his links to literature or politics. When he found some respite, he joined the ranks of the newly established Workers Party of Turkey (TİP) founded in 1961. In 1963 he stood as a candidate in parliamentary elections but did not win. In the local elections of 1965 he was elected to the Istanbul Municipal Council. The political arena at home had widened and opportunities to speak had increased. At the same time, his creativity flourished and he added translations from French to his writing. Then came the Military Memorandum of 12 March 1971, initiating Turkey’s second coup. This time Zaven Biberyan turned not to underwear, but to the toy trade, staying alive and raising his child by selling the objects he made with his own hands.

Throughout this time he wrote stories and novels in Armenian. He published a collection of short stories Dzovı (The Sea), and the novels Angudi Siraharner (Vagabond Lovers), Lıgırdadzı (Trollop, which was translated into Turkish during his lifetime as ‘The Lonely Ones’), and Sunset of the Ants. He translated Gorky, Jack London, Upton Sinclair and an abridged version of Aram Andonyan’s 1,100-page Balkan War.

This account was not written solely to explain the life of Zaven Biberyan. He met with the same oppression that was suffered by so many intellectuals working to make the homeland more liveable, more just. Like so many of them he saw prison, exile, want and poverty. Despite this he did not give up. He believed, he despaired, sometimes grew tired and weary but despite it all left a mark on this earth through his achievements: he owned a voice and words than would echo in some places after his death. Moreover, unlike his fellow Turkish intellectuals, he did all this while carrying an enormous ‘Armenian’ stamp on his forehead, and paid in full both for his opposition and the sin of that stamp.

Today, when we look out of the window at a 2016 Turkey once again turned into a jail under the State of Emergency, in our deep melancholy we can recognise the multitude of things revealed by Zaven Biberyan’s torture and jailing, by his exile and travails, by his climbing of the hill of Mahmutpaşa, just as the Jesus that he never got along with ascended to Golgotha with a cross on his back, by the resistance that crystallized in the strength, despite all this, to enter politics with the TİP in the 1960s, and by the patriotism that worked as the engine for that resistance!

His creation of works that are each a masterpiece in a language, Armenian, understood by only one in 100,000 in his homeland, a language that has been eradicated from its homeland; his creative perseverance, even though no one knew of these works; his translations to widen the cultural horizons of people who could not read them; and his refusal, while doing all this, to abandon his right and struggle to have a political say in the conditions of the country – this should serve as an example engraved in our minds of what we can do in hard times, what we must do.

Perhaps we need to start by accepting that our country has always been in a ‘state of emergency’. Sometimes less, sometimes more, but the space for words has always been narrow. The dominance of Turkish in language, Sunni Islam in religion, Turkishness in ethnicity, nationalism, the Right and capitalist liberalism in politics has, for those who differ in language, religion, ethnicity or opinion, always constrained not just words but life itself. The exceptional circumstances of today have always been unexceptional for the dissenting and discordant voices in this country. Ask the Kurds, ask the Armenians, ask the communists… Silence was imposed on them by the threat of violence and those who would not accept silence were crushed in a variety of ways. The country’s best writers, filmmakers, journalists, orators all ended up in jail. Cultures, languages, positions and ideals were erased, deprecated, declared the enemy. And most of the time such things were done, not under a State of Emergency as today, but the ‘normal’ state of affairs. This state of affairs was Turkey itself. Despite this, Yaşar Kemal was able to be Yaşar Kemal, and Sevgi Soysal to be Sevgi Soysal. Great writers such as Oğuz Atay and Adalet Ağaoğlu were able to emerge from these restrictions. The millstone threw its children outside its borders: Mehmet Uzun, one of the greatest writers of Kurdish, found his voice and language in Sweden, where the air and water are nothing like ours; Nâzım Hikmet wrote perhaps the most beautiful Turkish poems accompanied not by raki at a table by the Bosphorus, but trying to warm himself with vodka in the cold of Moscow.6

In his book Becoming Freud: The Making of a Psychoanalyst, the British psychoanalyst and writer Adam Phillips writes, ‘Modern people are as much the victims of their history as they are the architects’. We write our own history and, in doing so, chose and discard facts; to continue with life we have to make the truths bearable. It is always within our power not to make the history of which we are victims solely a history of victimhood: our history is simultaneously always a history of resistance.

After spending all my adult life seeing Turkey’s struggle for democratization as an adventure that would eventually achieve the good and true, today, particularly after what we have experienced in the past five years, I am heavily inclined to see the same history as a history of fluctuations, of tides that reach who knows where. A brutal but strong state tradition can somehow bring peace at various times, and pass on the violence it contains to new generations. This may be the essence of the Turkish Republic. The Tanzimat7 and modernization gave birth to Sultan Abdulhamit, the perpetrator of blood-soaked massacres; the same Abdulhamit who centralized power and guaranteed the survival of the state. Out of Abdulhamit came the Unionists, out of them came Kemalism, out of Kemalism the Democrat Party, out of that Turgut Ozal’s ANAP, the Demirel-Ciller DYP, and in a way Erbakan’s National View.8 The place where all these end up and which contains something from all of them, is Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP. The port he has reached while beating our heads with his ‘New Turkey’ along the way, is once again an atmosphere of civil war reminiscent of the 1990s, once again an authoritarianism like that of the 1930s and 1940s, once again nativism and nationalism, once again the National Chief, the Boss, the Commander-in-Chief.

Confronted with this dark picture, most of us, or if not ourselves then definitely some of those closest to us, have given up hope for our country. Some are planning a move abroad. Most of us struggle to answer the question of how to raise a child in this country. Because we are afraid: a single book, article, sometimes a one-sentence tweet, by chance in the wrong place at the wrong time, can mean prison, punishment, even death. There is no logical explanation for why so many journalists and writers are or have been in jail. In their place, it could have been me, or you, or another, but a blind sense of vengeance chose them, and we do not know who it will choose tomorrow. In such circumstances what could be more natural, more human, than fear, escape into cynicism, lethargy, passivity, retreat, decadence, hiding?

I will not start chasing the tail of some undefined hope. On the contrary, since the public landscape looks somehow hopeless, I suggest that we should not forget to live even if it is hopeless and incurable; that we should work to stay alive and, when the opportunity arises, to place stone upon stone, word upon word. This is the greatest achievement in the history of our civilisation. Because inside us, hidden in the depths, our wild nature always wants to be free, to cling to life. For this reason alone, in these hard days, we must cling to life like seaweed to a stone on the seashore. Maybe our voice will be weak – because we are afraid – maybe there will be days when we must be completely silent – because the risks are great and there is no end to evil – but sometimes a single word, a single action, a single gesture can change the flow of history. We must carry on with the work we know, we must press on with reading, writing, speaking – with our life. We must make the most of the hair’s breadth of chance we find to resist. We must shout if there is an opportunity to shout and write on walls if there is the opportunity. We must support those in jail, tell their cases to deaf ears. Whether we are jailed inside or jailed outside, we must find a way to resist. Because sometimes simply being aware of certain things and behaving accordingly – even just ‘being’ – is a form of resistance, and we can never know what tomorrow will bring. Whether inside, outside, or in exile…

Nâzım Hikmet spend 13 years of his life in prison, and 13 years in exile. In 1915 Zabel Yesayan9 was saved from death by escaping Turkey disguised as a Bulgarian nurse. Vedat Turkali was tortured, Ahmet Kaya died in exile.10 Remember Nelson Mandela, Primo Levi, Aung Sang Suu Kyi. They saw oppression but they remain in conversation with us and the future. The names of those who oppressed them are forgotten. If they are remembered, it will not be with approval. But the names and the ideas of their victims live. Today, a university student reads Zabel Yesayan’s Among the Ruins, a worker wakes with an Ahmet Kaya song on his lips, a teenager learns Tahir ile Zuhre11 to impress his or her beloved.

The fact that it became a cliché does not rob the obvious Gramsci quote of relevance: ‘a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will’. The powerful will never know the victory that grows out of successive defeats, because it is we who know how to lose. In times of defeat we know how to resist, to show the will to raise our heads. When the time comes, we know when to sell underwear, when to sell toys, when to do translations or to shout the principles in which we believe into the face of power. If we can manage to be organized, we start with our organizations, if not, alone, in pairs, with those closest to us.

Our space and our clothes are tight, but so what!12 The light of creativity shines brightest in the darkness.

Discriminatory tax levied disproportionately on non-Muslims.

Selective conscription that placed non-Muslim minorities into labour battalions.

Prominent intellectuals including novelists, poets, writers, politicians and musicians.

Leading Armenian writers, poets, painters and journalists.

Poet, 1902–1963.

Yaşar Kemal: novelist 1923–2015; Sevgi Soysal: novelist 1936–1976; Oğuz Atay: novelist 1934–1977; Adalet Ağaoğlu: novelist and playwright 1929–; Mehmet Uzun: novelist 1953–2007, in exile from 1977.

Nineteenth century reforms to the Ottoman Empire designed to adopt some European practices and halt decline and nationalism within the empire.

Major twentieth-century political forces in Turkey, culminating in the Islamic nationalist National View movement.

Novelist 1878–1943. A survivor of Armenian Genocide, she was killed during Stalinist persecutions.

Vedat Turkali: novelist and screenplay writer, 1919–2016, spent 7 years in prison during the 1950s for membership of the Turkish Communist Party; Ahmet Kaya, Kurdish singer 1957–2000, who fled to Paris after announcing plans to sing in Kurdish.

A poem by Nâzım Hikmet.

The words of a song by Sezen Aksu. In Turkish, the saying ‘to have tight sleeves’ means to be hemmed in or restricted.

Published 31 January 2017

Original in Turkish

Translated by

Steve Bryant

First published by Varlik 11/2016

© Rober Koptaş / Varlik / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Parables of violence; memories of dictatorship; perversions of memory: Ord&Bild samples contemporary Latin American literature and photography.