Operetta wars on a pandemic

Decades of cuts to public health are now exposed as the spread of the coronavirus overwhelms the system. Europe has been lucky to observe hurricanes, floods and plagues of the past decades from afar, but geography or wealth doesn’t safeguard us from epidemics. How we treat our least powerful now will be telling about what we can hope for.

Downscaling heavily polluting industries and recalibrating consumer culture are inevitable if we are to avoid an even bigger crisis than the one we are now facing. But the response to climate catastrophe is being constantly postponed. Now, with a plague on our heels, there is no ‘remind me tomorrow’.

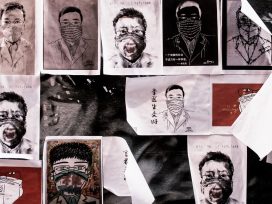

Illustration by Frank R. Schröder from iHeartBerlin.

Lockdowns and quarantines are announced daily throughout the world, while estimates vary hugely as to how long the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic will last. The virus launched its world tour in Wuhan, China, last December and was not considered a serious threat until late January. In fact, some were still likening it to seasonal influenza until as late as last week.

Understatement is characteristic of this crisis, probably due to a combination of factors. One of them is the numbing effect of the perpetual hysteria that is commercial news. Another is political: authoritarian regimes have formed a choir in downplaying the gravity of the outbreaks, trying to shift the blame from their own failing responses.

In public spheres laced with shameless propaganda and misinformation, the general mistrust toward authorities and the media makes it hard to decide which measures are reasonable and which are overkill. It’s even stranger to see illiberal leaders who have built their careers on fearmongering – in Hungarian we call it ‘operetta wars’ – now belittling the threats. Péter Krekó and Patrik Szicherle survey the disinformation that accompanies the coronavirus, spread not only by commercial clickbait outlets, but also by official political communication.

The failings have been inevitable, however. When leadership looks for political benefit in dealing with emergencies, it will always cause harm. The past decades’ austerity measures and cuts to public health – from care networks to hospitals and research capacities – are exposed when a situation like this overwhelms already overwhelmed systems. The same logic that calls for shifting health and care from a universal welfare regime to commercial services promotes the delegation of health issues to the individual – a trend that Caroline Molloy recently wrote about. This too is being called out by the rampant disease, whose constraint relies on millions retreating to their homes – if they have one. Under lockdown, it’s up to the individual how much caution they take, but also to assess when they require help.

Epidemics and other emergencies can never be left to individual responsibility and the good will of insurance companies. No market will miraculously provide epidemiology, because it relies on universal coverage to be effective. Outbreaks cannot possibly be curbed by servicing only those who can afford the care.

The containment efforts also hit hardest those who are already vulnerable. Social distancing, the foremost preventive strategy, takes its toll on the most precarious industries, including construction, hospitality and, of course, culture. All those working on casual contracts, in the gig economy, or as freelancers are now suddenly without income and have no employer that owes them help. The most precarious are least likely to own real estate or to have financial reserves – and yet they will have to keep paying their rents or mortgages regardless.

With a housing crisis already raging, the coronavirus lockdowns threaten another collapse, this time for insecure tenants. Bailouts will be desperately needed. But the 2008 financial crisis casts a long shadow. Once again, it is people and not corporations that need a rescue package, including those already in homelessness or threatened by it. Aviation companies and the cruise ship industry should be less of a priority.

This pandemic bears the essence of the globalization of capital on a physiological level. The coronavirus was able to spread this fast because intercontinental travel has become almost compulsory to status – via excessive holidays or business travels – or to maintaining family ties and identity when living far away from home. These take a toll on the environment and the individual. But each person is expected to bear the consequences themselves, preferably without complaining about distance and detachment, but proudly collecting air miles.

In eastern Europe, for example, outmigration poses an existential threat to smaller nations, writes Slavenka Drakulić. Although nationalists discuss migration with hostility, their economies rely on a displaced and desperate labour force – a paradox detailed by Thomas Nail. The constant motion of these displaced people exposes them to threats which they end up being blamed for.

This is what it looks like when globalization collapses. Flights and tourism shut down, international commerce and outsourced manufacturing go out of the window. Perversely, emission rates have fallen drastically. Empty streets urge us to imagine public spaces without mass tourism. Empty supermarket shelves force us to reassess what we consider necessities. Some people stock up on pulses and flour while others fight over toilet paper.

In Budapest, where I live with my family, yeast is now almost nowhere to be found – the instincts of the socialist scarcity economy quickly switched back on. At the hands of a centralized propaganda machine operated by an illiberal government, we have all the circus we will ever need, so all we have to care for now is bread.

The lockdown comes with much milder consequences than an energy shortage or a mediocre weather disaster. Our cities are not prepared for even a day of self-sufficiency should power run out for any reason. In glass houses without openable windows, we circulate air through ventilation systems, creating the perfect breeding ground for contagion and rendering these buildings uninhabitable the minute electricity runs out. We build without bearing resilience in mind, or without thinking of those we leave behind.

Europe has been lucky to have observed from afar the devastation caused by hurricanes, floods and plagues on other continents in the past decade. But geography or wealth do not safeguard us from collapses like the one we are now facing – and the ones that are coming.

It is still uncertain whether we will rise to the occasion and take the measures necessary to prevent pandemics or the troubles the environment has in store for us. How we treat our least powerful now will be telling about what we can hope for.

This editorial is part of our 5/2020 newsletter. Subscribe here to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 19 March 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Deforestation and reforestation

Revue Projet 4/2025

Why forest restoration projects are counterproductive; how citizens are mobilizing to protect Europe’s woodland from the right; and why diversity is the solution to sustainable timber.

Writing on the wall, writing on the water

Notes towards a reservoirian aesthetic

Engineered flooding displaces communities, eradicating the landmarks of family histories. When little remains, narratives about who controls water provide telling pointers – feature films raise complex questions about industrialization, linguistic minorities, and matriarchy versus youthful masculinity.