It should come as no surprise that we Belarusians are called a nation with an almost obliterated sense of identity: we have virtually lost our culture and language, our national architectural style and the architectonic legacy of our towns and cities. Even our churches have been rebuilt in the Russian manner: instead of crosses they have Russian ‘cupolas’, popularly known as ‘onion domes’. We are now in the 229th year of the Russian occupation. Virtually nothing is left of what we can call our own.

This is what I also thought until 2020, when the noose around our necks was loosened a little. Belarusians came out in their millions to demonstrate for what they really wanted. There were meetings and processions even in small towns and villages that had previously seemed devoid of all life.

But then Putin announced that he would send in troops, and Łukašenka – backed by the Russian ruler and thousands of thugs acting as the forces of ‘law and order’ – crushed the protest by shooting people on the streets. Three years later, the brutal repressions continue. A prison system has been established in Belarus comparable to the camps set up by Stalin and Hitler, the only difference being that there have been no mass killings.

For months, now, the relatives of political prisoners have heard no news. We know that some, for example the blogger Ihar Łosik, have attempted suicide. Others, like Ivan Klimovič, a 61-year-old with heart problems, have died because they received no medical attention. Klimovič was imprisoned for posting a caricature of Łukašenka on social media. At his trial he said to the prosecutor and the judge, both ruddy-cheeked, healthy men of 30, ‘Don’t imprison me, the doctors say I’ll die there.’ They went and locked him up anyway.

The 50-year-old activist Vitold Ašurak was simply killed. All his bones were broken. His body was passed to his relatives with the words ‘He had a bad fall’.

The 11 July 2023 was a black day for Belarus: Aleś Puškin died while serving a five-year sentence in a labour colony. He was not only a political prisoner; he was an artist whose paintings depicted the Belarus we saw in our dreams, with a wonderful past and a bright future. This is how we have had our dreams taken away.

There are many thousands of such stories, but even recording them is a demanding task: human rights activists and defence lawyers have been handed down lengthy prison sentences and disappear behind bars.

At this point an obvious question arises: are the Russians alone guilty of what is happening in our country? The shooting, repression and killing of tens of thousands of people require an equal number of fellow countrymen prepared to inflict such harsh punishments on their own kind. Where do these people come from? Who are they?

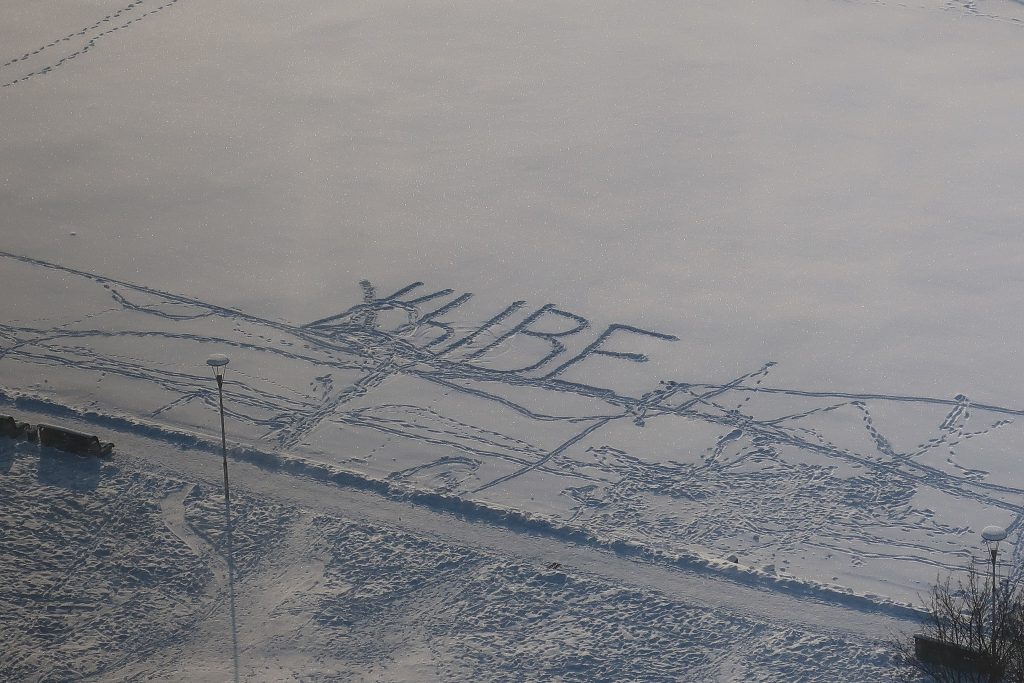

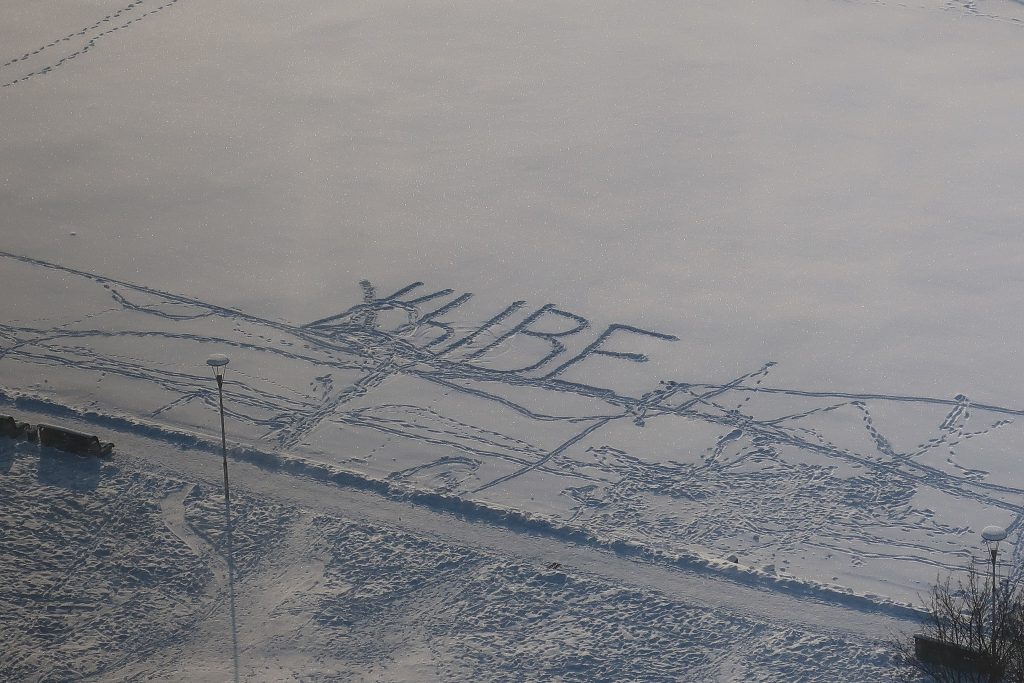

‘Жыве [Беларусь]’ / ‘Long live [Belarus]’. Minsk 2021. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Homoatrox)

Ethnocide as a form of genocide

The 500-year-old Russian Empire has existed in a variety of guises – first as Tsarist Russia, then as the USSR, and now as Putin’s Monster. It has assembled an effective toolkit for the conquest of foreign lands, which explains why the empire takes up one seventh of the Earth’s land mass. Its methods combine the physical annihilation of the elite of the occupied territory with the obliteration of people’s identities and their re-education as Russians. What is happening in Ukraine today is a good example: parents are killed and orphans are carted off in their thousands to special camps in the depths of Russia, or to families where they will be indoctrinated and taught to hate their motherland and their own families.

This is what has been happening to the Belarusians for the past 229 years. The policy reached its climax in 1937 with the murder of the Belarusian intellectual elite – specialists from all walks of life, artists, doctors, engineers. On 29 October 1937 alone, more than one hundred writers, poets and scientists were shot and their bodies dumped in mass graves in the forests. Every small town in Belarus has a ‘shooting site’; the locals know what happened, activists have managed to compile lists of names and commemorate the dead. The land has a long memory.

The second stage of ethnocide is the eradication of the Belarusian language, culture and education. Children in Belarus now receive their education in Russian; in some cases the teaching of Belarusian language and literature takes up no more than one hour a week. There is no Belarusian-language higher education; all university-level institutions teach in Russian.

People who have grown up in the bosom of the Russian mentality regard everything Belarusian either as a backward, rustic oddity or as a hostile element in society.

Just like in the occupied territories of Ukraine, our very own quasi-occupational administration is busy with the breaking and crushing of national self-identity. Anyone who has not fled the country is in prison or keeping a low profile, afraid of losing their jobs, their possessions, their children. These are the methods. People are deprived of their belongings to pay huge fines. Without a job or an income they face the constant threat of having their children being taken into homes or being given to foster families. They are forced to become the kind of people that Russia wishes to see: like the people who live in Luhansk, Donetsk and the other occupied territories of Ukraine – almost-Russians, the bearers of the ‘Russian idea’ but not fully accepted in the heartland of empire. They are poor imitations of proper Russians, but they represent the ‘Russian world’ and serve as a buffer between primordial Russia and the ‘accursed West’.

This is what they want to turn us into when they actively erase Belarusian and Ukrainian identity. With the Belarusians they use what one might call ‘cold genocide’ – force and repression. The ‘hot genocide’ in Ukraine involves killing people in their own homes. At times the ethnocide is cool and calculated, at others it is stupid, a mere caricature. Either way, the process of wiping us from the face of the Earth continues.

How do we resist?

Active and visible forms of resistance are possible only in the diaspora. Belarusians have created military formations to fight on the side of Ukraine: the Kastuś Kalinoǔski Regiment, the Pahonia Regiment, and the Belarusian Volunteer Corps, including the ‘Terror’ Battalion. Abroad we publish books and textbooks in Belarusian, we educate our children, we collect donations to pass on to the families of political prisoners who otherwise have no means of survival. We raise money for the treatment of those injured and crippled during the protests or in the war. We have a government-in-exile and our own organisations.

But what about resistance within Belarus itself? The unprecedented severity of the repressions has made open resistance impossible. People are given lengthy jail sentences for a simple ‘like’ on Facebook, for subscribing to a ‘wrong’ Telegram channel, for a word uttered in the wrong place to the wrong person, for no reason whatsoever, or because someone has denounced you.

But people have come to realise that in such conditions they must unite and help each other, no matter how. They form readers’ clubs, clubs for lovers of embroidery or papercut art, groups for young parents, clubs for animal lovers or sports fans. People remember their experiences in 2020 and strive to preserve them as best they can. There is a widespread conviction that we are at a turning point in history, that we must be prepared to break out anew at any moment, so that we can take back control of our country and our lives.

But there is another, even more important task at hand: to collect the names of the judges, prosecutors, police officers, members of the special services, prison warders, teachers, propagandists and informers – all those who have taken part in breaking people’s lives, in killing, beating and crippling them, in abusing and humiliating them, and in falsifying elections. After Belarus has been liberated, there will be a huge trial for the prosecution of evil. A process of lustration will take place in which all those who have abused their powers will be disqualified from holding public office. This is something that we failed to do after the collapse of the USSR: it was not the right historical moment, and the right opportunity did not present itself.

Legislative work is underway both in the underground in Belarus and the diaspora. The ground is being prepared for the prosecution of crimes committed by Alaksandr Łukašenka’s pro-Russian regime and those who issued criminal orders or carried them out. A legislative framework is being developed for the normalisation of life that will include the creation of a non-repressive public education system, the changing of the official language of education and government to solely Belarusian, and the creation of proper conditions for the freedom of the mass media and business.

Belarus had a taste of freedom during the short period between the declaration of independence in 1991 and the rise to power of the pro-Russian dictator Alaksandr Łukašenka in 1994. It took a great step forward – so great that we amazed even ourselves. The first green shoots of liberty and prosperity appeared. Culture, business, a free press, a healthy economy and education system all began to take shape before our eyes. People saw that it was possible to live their lives as they wanted and there were opportunities for them to do that; that they no longer needed to conform to the dictates of party, state or ideology.

How we ended up in a totalitarian state

There is a proverb: the first pancake always goes wrong. This was the first and last pancake that we have been permitted to mix and cook for ourselves. At no time during those 229 years of Russian occupation (one that was interrupted only by other occupations, German or Polish) have Belarusians had any experience of free elections or a free press. It’s a miracle that we still want anything at all, that we still have an urge to live our own lives, that we would still prefer to cook our own pancakes rather than feed from foreign hands.

When Łukašenka came to power in 1994 after the only free elections the country had ever known, Belarus was suffering under a severe economic crisis. Pensioners, who made up a quarter of the population, were no longer receiving their pensions. Ninety percent of the country’s workforce was employed in state-owned enterprises and the state had stopped paying wages. Whatever it did manage to pay was eaten away by inflation. It was evident that the crisis could be overcome by the entrepreneurial initiative of people ready to work hard. But the elderly and impoverished sections of the electorate could not wait. So when Łukašenka offered himself as a candidate, promising to end to post-Soviet corruption, restart the gigantic Soviet factories, and provide work, order and stability, people rushed to vote for him. They liked the idea of a strong arm at the helm, someone to run the state for them and instil order. They just didn’t know that this strong arm would gradually take them by the throat.

Łukašenka fulfilled his promises to feed the hungry. He immediately concluded a union with Russia, which boiled down to Belarus becoming a vassal state, a component element of the ‘Russian World’ in which Russian ideology and culture prevail. Russia pays the piper and calls the tune. In return Łukašenka was handed unlimited power. That’s how things have been since 1994. Every few years, when elections come around, Belarusians have stood up to the regime; their activities have been witnessed, chronicled and included in election monitoring reports. The struggle has gone on untiringly, but we have not been able to overthrow or even shake the regime.

There are those who blame the free world and the international community for not having supported us enough. This is not a view I share. Western countries have helped our oppositional and cultural activities financially and with advice, education and publicity. The support they have given us has been colossal.

But Russia opposed our freedom. Throughout the years of favourable market conditions for its natural resources, Russia funded its imperial projects in all parts of the world. It has shelled out many billions of euros on supporting the Belarusian regime alone. In the West, huge sums have gone to buy the favours of the political and business elites – all the well-known agents of Russian influence in London, Berlin, Paris, Warsaw, Prague and the Balkan capitals. Money to purchase agents throughout the world goes through the offices of the influential ‘Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation’, known as ‘Rossotrudnichestvo’ for short.

It might have been possible to somehow overcome all this were it not for the internal divisions within the Belarusian nation. As a direct result of Russia’s centuries-long military, cultural, economic, mental and ideological domination, a large part of our nation has adopted the mentality of the ‘Russian World’. There are many who are happy to live in an empire of inhumane grandeur, ordinary everyday violence, hostility and evil. That is why we lost. And for that loss we have paid with the transition from an authoritarian state to a totalitarian one.

As we know, there is a huge difference between authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. An authoritarian regime says to its subjects: ‘Do what you like in your private lives but keep out of politics.’ A totalitarian regime, on the other hand, creeps into bed with its subjects, sits at their table, follows them into the bathroom. If necessary it tears from them any veil of privacy or intimacy and deprives them of the right to their own body. Totalitarian regimes reached their culmination in Kampuchea, where prisoners were forbidden from moving without permission. Anyone making an unsanctioned movement was killed on the spot. Of all the tens of thousands of people locked up in those prisons, just two survived.

The citizens of Belarus are living through the final stages of totalitarianism. There is just one small loophole left to us: we can escape to the free world. Although, of course, not all of us can. Some are sick and poor, others are imprisoned, yet others have elderly parents. Even so, the neighbouring states of Lithuania and Poland – countries that are culturally and historically close to us – report that since 2020 there has been a sharp increase in emigration from Belarus, with numbers continuing to grow.

The authorities turn a blind eye in the hope they will be rid of all those who oppose the regime and could foment unrest. But now the specialists essential for the functioning of the state have also begun to leave. Thousands of doctors, technical specialists and scientists have escaped. A young Belarusian engineer I met recently in Warsaw told me that the director of the firm he worked for wouldn’t let him go. So he abandoned his documents and was sacked under the relevant article of the Labour Code – meaning that he is blacklisted for any future employment in Belarus. ‘I want to retrain as a long-distance lorry driver and bring my family here,’ he said to me. ‘In five years I’ll be getting old, I’ll start getting sick and won’t be able to get out or get my kids out either.’

Computer programmers are also escaping. The Belarusian regime used to be proud of them. It built a technopark for them and boasted of its innovative spirit to the whole world. One of the programmers went back to Belarus to bury his father. He was detained at the frontier. His travel documents (passport, ‘Polish card’, Polish work permit) were put in the shredder and he was compelled to stay in Belarus.

Will there be an iron curtain on the frontier with the West? Elements of it are already in place. The authorities have created a mental and physical gulf between us and our nearest neighbours, the Poles, with whom we shared a state for several centuries. Belarusians wait at the border crossing points for up to 24 hours to get into Poland. They have their Polish labour permits checked and are often denied permission to travel further. We are even made to live on Moscow time, with the result that there can be up to two hours’ difference between Belarus and Poland. When it is 11 in the morning in Brest, it will still be 9 in Terespol, just fifteen minutes away.

Boiling frog syndrome

Aside from a quite deliberate helplessness, one consequence of living under a totalitarian regime is a sense of deprivation. It arises from a limited opportunity for satisfying one’s basic needs – psychological, physical and social. You are no longer fully aware of who you are or what you want. It’s very much like the Russian fairy tale that we were shown for years and years on television, where one of the characters says, ‘freedom, slavery, it’s all the same’. Even the brightest, best and most energetic people give up and retreat into their private life, into another culture, or simply into depression and alcohol.

A singer who organised street choirs with thousands of participants during the 2020 protests in Belarus said to me in Warsaw on 7 May 2023, ‘I don’t organise street choirs anymore. There’s no point. Our songs didn’t get us anywhere.’ This was a strong, motivated, steadfast man who hasn’t given up. He helps dozens of Belarusian political refugees find their feet in Poland. Without him, whole families would be unable to secure somewhere to live, get a job or a school for their children. But some people retreat into themselves; they eat and drink too much, as though they were trying to commit slow suicide. This is common when people have lost hope or are in the process of losing it.

As I write, I am well aware that Pavieł Biełavus, the manager of a shop in Minsk that sold Belarus-related items such as souvenirs and books, has after a long detention in custody at last been told what he is accused of: ‘spreading Belarusian nationalism’. The state openly acknowledges that it long ago ceased to be a state. It is an anti-Belarusian, anti-national administration of an occupying power.

What can save us, then, apart from the Ukrainian Armed Forces and the Belarusian units fighting alongside them for the defeat of our common enemy, which for centuries has sought to destroy our lives, our freedom and our happiness?

Is this the end? No

Love. It is within our power to preserve our identity. If you lack the strength to do something or to unite with others, nurture that love safe within yourself, like a spark – love for yourself and for whatever is yours. Under the right conditions, that spark will set off a fire that will blaze to the heavens in flames that are tall and mighty. This is what we witnessed in 2020, when it seemed as though each apartment, each family had a white-red-white flag of its own; for this people are now being sent to prison, from which they may never return.

The love of freedom, of creation, of self-realisation acts as a powerful stimulus. As the Belarusian proverb says: ‘Not even a horse can drag you away from your beloved.’ The soul is naturally drawn to children, the loved one, parents and home, in the same way it is drawn to the Belarusian inside you. Especially at a time when all that is yours is impoverished and enslaved.

The main thing is not to lose hope and, even when weighed down by pain, deprivation, helplessness and sorrow, to go on cherishing and developing that sense of being Belarusian. No special reflection is necessary, no striving for perfection – that is just another sign of slavery. ‘I’ll be the very best kind of Belarusian; I’ll save us all and defeat the lot of them; I’ll be a hero and a true activist; I will assume the burden of obligation and memory, and suffering will make me superhuman.’ None of this is necessary. Love is all you need. Be joyful.

One day all of this will come to an end. Totalitarian regimes always come crashing down suddenly; they are the enemies of love, liberty, hedonism and joy – all the brightest features of humanity. We have been given a painful vaccination against totalitarian dictators and foreign ideologies like the ‘Russian World’. And so, when we come to create a party to scrub our age-old grey boulders clean of the stupid slogans they have been daubed with, we will restore our town halls, market places and squares – everything that was demolished during the reign of the Russians. We will take down the onion domes from our churches. We will re-create Belarus as God made it, because without Belarus the world is incomplete. And we will name this party after Michał Aniempadzistaǔ, the artist and poet who understood Belarus better than anyone.

These will not be easy times for us. But for the sake of the beloved it is possible to raise mountains and tilt the sky.

Long live Belarus!

The translation of this article has been funded by the S. Fischer Foundation