Ocean justice

Treasure trove or rubbish dump? In either case, oceans are being spoiled. Concepts from ‘mare liberum’ to ‘common heritage’ don’t safeguard the blue planet’s largest frontier from escalated seabed mining, industrialised fishing and waste disposal, nor global inequality and racialized violence. Could a democratic World Ocean Authority be the answer?

Political theorist Chris Armstrong argues that global justice urgently needs to include oceans. In his conversation with Antje Scharenberg for the UK publication Soundings, he discusses his latest book A Blue New Deal: Why we need a new politics for the ocean.

Antje Scharenberg: Let’s begin with some statistics. Your book starts with the statement that the ocean covers 70% of our planet’s surface. To me, facts like this illustrate both humanity’s essential dependency on the sea (which produces half of the oxygen we breathe) and our global political economy’s dependency on the ocean (which carries the vast majority of goods we consume through cargo ships, and most transatlantic data traffic through subsea cables). One of my favourite, mind-boggling, ocean facts is that approximately half of the planet’s surface is covered by the high seas – that is, territory outside of national jurisdiction.

Chris Armstrong: It’s even more mind-boggling if we think in terms of volume. We often think about the ocean as a surface – it is the surface of the world that is 70% sea. But if you think in terms of volume, the fact is that more than 95% of liveable volume in the world is ocean, because it’s so deep. I also like telling people that when I went to school I was told that the rainforests were the ‘lungs of the earth’ because they absorb the carbon dioxide and release the oxygen. But actually the ocean better deserves that title, because it is probably the biggest carbon sink, and it releases at least half of the world’s oxygen. The ocean can be thought of as anvincredible carbon pump. It absorbs carbon through phytoplankton, zooplankton and then fish. When the fish die they fall to the seabed and the carbon gets locked away for years and years. This is an incredible process, which tends to get left out of our mental picture of the climate, which is often all about trees.

Antje Scharenberg: So that’s the first reason why we may want to start demanding a Blue as well as a Green New Deal.

Chris Armstrong: Absolutely. And another important issue here is the question of ‘Blue Acceleration’. Since WWII we have seen an incredible growth in a whole series of ocean-based industries: fossil fuel extraction, the exploitation of marine genetic resources, industrial fishing and so on. All these industries are outpacing growth in the global economy as a whole. The Blue Acceleration hypothesis basically suggests that the share of the global economy that comes from the ocean is going to keep right on growing and growing. Clearly that in itself is a normative vision: it assumes that the ocean is there simply for us, to enable us to keep on consuming, that it is endlessly available to us. That’s a picture you get from the economists and from lots of policy-makers: the ocean is the future and we just have to identify and tap into these incredible opportunities. This is a narrative we have to dislodge. At the moment there is very little regulation of these industries, and big companies are being allowed to exploit these resources without any regard to issues of distributional or ecological justice.

Antje Scharenberg: Let’s expand a little on the role of the ocean in our political economy, which seems to be less publicly known about than the environmental threats it faces as an ecosystem. Your book is part of a growing scholarly discussion about the role that the sea has played for the origins and development of capitalism as we know it today. I’m thinking here, for instance, of Laleh Khalili’s Sinews of War and Trade, from 2020, or Liam Campling and Alejandro Colás’s

Capitalism and the Sea, from 2021.1 What I particularly like about your work is that you come to the ocean from an original interest in questions of distributive and global justice.

Chris Armstrong: Exactly. I’ve been working on global justice for quite a few years, increasingly turning also towards environmental issues. The obvious entry point for people working in global justice is to then talk about climate justice and what climate justice might look like. Then, more recently, I and lots of other people have become more interested in the biodiversity crisis, which also has its global justice dimensions. I think there’s a slowly dawning realisation that the ocean sits at the centre of all those problems. It has an enormous global justice dimension, and it’s massively bound up in the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis, but there’s often an ocean-shaped hole in discussions on these issues. Yet the ocean is a big, if not the world’s biggest, carbon sink, and it is home to massive amounts of biodiversity and a growing slice of the world economy. I think the ocean needs to be really foregrounded in all of our discussions about global justice. Decisions that we make about how to govern the ocean have enormous ramifications for what the global economy looks like – and what the global environment looks like – in the coming decades. I think the ocean should command our attention in terms of its scale, our dependence on it, and its role in our economic future.

Antje Scharenberg: This seeming lack of attention to the ocean from a global justice perspective is definitely something I’ve also noticed in my work on transnational mobilisations. One really striking example is the overlooking of the crucial importance of the global fishermen’s movement for the alter-globalisation movements and the struggle against neoliberal globalisation – something that has received curiously little attention from either scholars or activists, as noted by the feminist writer Silvia Federici in her foreword to Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Monica Chilese’s book Our Mother Ocean.2

Chris Armstrong: That makes me think of another interesting historical movement that grappled with questions around global justice, resource sovereignty and egalitarianism on a world scale – the movement in support of a new international economic order which emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. This is discussed in a great book from 2019 called Worldmaking After Empire by Adom Getachew, which starts from the observation that, in retrospective discussions about the decolonisation struggle, political independence tends to get presented as the only thing that formerly colonised countries and their leaders in Africa, Latin America and Asia were arguing for.3 Whereas, as Getachew argues, that actually was only half of what they wanted. Political independence wouldn’t have much value if they didn’t also have economic independence. However, economic independence was impossible because of the structures of the global economy. They campaigned for changes in the world’s economic power structures, in the belief, for example, that gaining resource sovereignty would only have real value if they managed at the same time to radically change their position in the world economy. So Getachew’s book is all about the other side of the decolonisation struggle, which is about having a different, more democratic, global order.

The really important ocean dimension to that discussion about the international economic order is often neglected – but in fact the idea of a new international economic order takes us straight into the question about seabed minerals. That’s one place where formerly colonised countries could find a driver of economic independence – they could have this socialist model of extraction of seabed minerals, with the proceeds being shared with other formerly colonised countries, thus removing their economic dependence on the old colonial powers through an alternative stream of revenue. So there already exists a rival imaginary about what a just world order could look like, and the idea that maybe it could be birthed in the seabed.

Antje Scharenberg: I agree that it’s really interesting to think about the ocean as a birthplace of alternative visions of a new global economic order based around notions of commons and sharing resources. Your example reminds me about Elisabeth Mann Borgese, who was part of a wider international movement – including the decolonial actors you mentioned – which worked towards a new global order in the 1940s and 50s. Mann Borgese became a global spokesperson for the ocean, based on a similar set of ideas about developing a new world order in the aftermath of WWII. What’s inspiring about her story to me is her conclusion that the ocean could function as a political laboratory from which more egalitarian alternatives and world orders might emerge. Her work was foundational to ideas about how the high seas should be legally governed and the eventual setting up of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which declares that the deep seabed is the common heritage of humankind. However, despite this legal position of course, far from being treated as a commons, the way in which the ocean is governed at present – de facto by multi-national companies – serves to enhance global inequality, as you argue in your book.

Chris Armstrong: That is certainly what is currently happening. The spoils of the new ocean industries, which are environmentally destructive in so many ways, are currently flowing to the ‘haves’, not the ‘have nots’. Lots of these ocean industries are highly capital intensive. Not just anyone can go out there and mine the deep sea bed or explore marine genetic resources. This is the preserve of big multinational corporations because the barrier to entry is so high. So the worry is that we will

get a spiralling of the Blue Acceleration, which will accentuate global inequality as well as damaging the oceans. In this sense, the ocean could be a source of even more inequality. The ocean economy is dominated by ‘keystone actors’: whether you look at industrial fishing, offshore fossil fuels, the marine genetic resources industry, shipping, whatever the sector – in all of these industries there are around ten companies that have half of all the revenues globally. It’s a hugely oligarchic sector. Whichever industry you look at, there is a pattern of massively unequal exploitation of these opportunities.

Antje Scharenberg: This raises the question of who governs the ocean at the moment, especially as there are at present few global institutions that actually have the power to regulate these big players in the global ocean economy. In your book you identify two problems in this regard. Firstly, there is a lack of institutions dealing with this question. For instance, why don’t we have ministries of the ocean in most countries? Secondly, where institutions exist, multinational companies have a lot of power in shaping their agendas – partly because so few politicians concern themselves with the ocean agenda. A lot of the discussions take place completely off the radar of institutional politics. One example here, which you discuss in your book, is the case of deep sea mining and the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which has what are arguably mutually exclusive remits – to fairly distribute the shared resources of the deep seabed while simultaneously protecting its ecosystem. You describe a scene that took place at an ISA meeting in Kingston, Jamaica, in 2019, when it turned out that the representatives of Belgium and of the Southern Pacific Island state of Nauru were mining corporation executives, rather than government officials – as was made public by Greenpeace at the time. What does this scene tell us about where ocean governance is going wrong today, and about how ‘our current institutions of oceanic governance are failing us’, as you put it?

Chris Armstrong: Sometimes when I do talks, especially to a less specialist audience, people ask what they can do if they care about the ocean: can I go and beachcomb and pick up some plastic? Of course, that can be important, but this is an individualised response – it’s not going to shift the structures that govern the ocean. And that is precisely the challenge for people who want to change the politics – what can they do to challenge the structures? Where is the politics of the ocean? It’s always hiding. In some ways it’s hiding in plain sight: there are organisations like the IMO and the ISA, which meet in public, more or less – they have observers, journalists can go there and so on. But there is no contestation of any of the decisions that get made there. Politicians don’t open those issues up to public debate. They don’t campaign on these issues or put them in their manifestos. We don’t get the chance to choose between competing visions of what the ocean should look like. Given that kind of vacuum, we have the perfect neoliberal picture, which is that corporations can form incredibly cosy relationships with governments, and they are allowed to extract resources at will, with no strings attached – and in fact they can also attract subsidies.

Take high seas fishing, for example. This industry simply would not exist without enormous fuel subsidies. It’s so expensive to fuel your ship just to get out onto the high seas that you’re making a loss by the time you get there. The only reason that this enormously destructive practice exists is because domestic fishing lobbies in countries like Japan, the UK and several other countries have managed to persuade political leaders that they need support. This is pretty noteworthy, given that the ships employ fewer and fewer people. Also, many of the people that are employed

on the fishing ships are not citizens – nor voters – in the countries of the owners – they are from much poorer countries, and are very likely to be exploited and under-paid. It’s a really bizarre picture of a small number of corporations having these very cosy relationships with governments, and extracting benefits from those governments, in order to engage in a pursuit which is basically destructive of the environment and exploitative of labour.

At no stage of this process is this close relationship subject to any kind of political debate. We don’t have any public campaigns about subsidies for high seas fishing, or the techniques that they use in high seas fishing. It’s perfect if you’re a corporation – you get all of the benefits and have no accountability. As you mentioned, we do not have ministries of the ocean. We have ministries of fishing, which are largely in the business of protecting these highly oligarchic industries. They’re not even trying to protect local employment – and they certainly have

little interest in the welfare of those they do employ. There’s no question of trying to protect impoverished coastal communities by helping them enter the fishing industry. These ministries are largely engaged in protecting a small number of companies that, over time, have bought up fishing rights.

Fishing quotas is another example. If you own an ITQ [individual transferable quota], it gives you the right to fish in a particular place at a particular time, and that has become an asset you can buy and sell. Lots of traditional fishing folk in places like Iceland and Britain have ended up selling them because you can make a nice and fast profit, but this means that the industry is becoming increasingly concentrated. Then these fishing companies start to leverage their assets. They start to get loans on the basis of these assets, and to invest in all kinds of other sectors of the economy. In Iceland fishing became part of the financial bubble – which popped in 2008-9 – so the fishing industry played a role in kickstarting the global financial crisis.

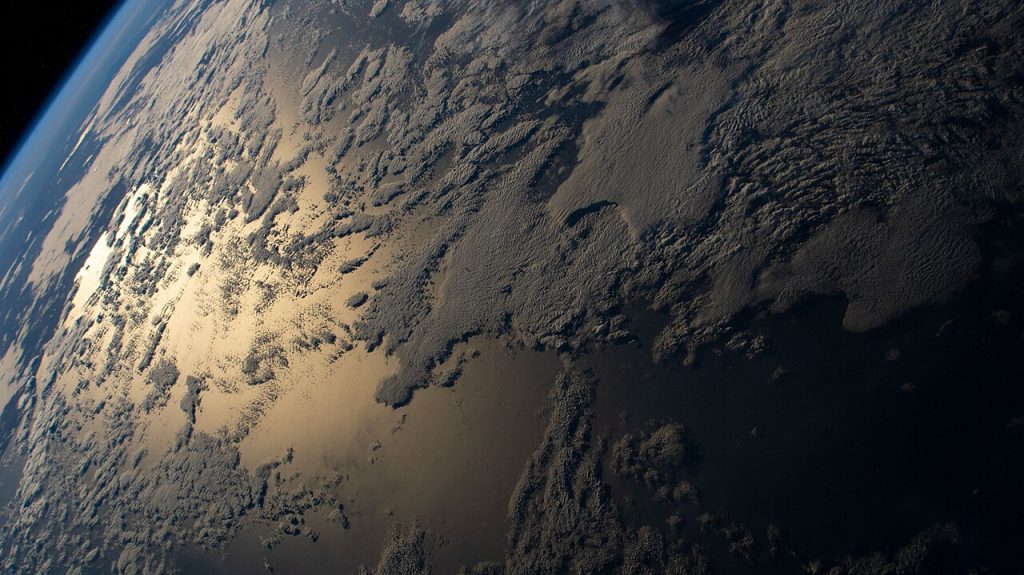

Sun glinting off the Indian Ocean, image from International Space Station orbiting 269 miles above south of Western Australia, NASA. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Antje Scharenberg: What’s really striking is the contrast between all these activities and what we were talking about at the beginning: the fact that half of the planet’s surface is covered by an area that lies outside of national jurisdiction – the high seas – and belongs to all humankind. We seem to have no way of governing that democratically.

Chris Armstrong: For sure. There are political processes going on, but they’re not democratic ones. It’s become incredibly technocratic. Take the language of the IMO – it’s a language of technical expertise. If you turn up and start talking about ecological crisis and social justice they don’t understand it. Another example is the incredible sleight of hand that happened in 1982, at the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS): they decided to turn 40% of the ocean into state territory through accepting the concept of exclusive economic zones in the sea, and the

extension of a nation’s ownership of the seabed as far as the continental shelf of its coastline. But where was the political discussion about that? I’m certainly not aware that that was accompanied by any public discussions of the options. It was the largest land grab in history. Overnight, well over 20% of the planet became state territory, and yet this was completely unaccompanied by any kind of contestation. UNCLOS doesn’t even justify it, it doesn’t even provide any normative justification for ocean enclosure. It’s incredible really. The focus seems

mainly to have been on how to divvy up and regulate territorial rights in the new international regime – there was no idea of any discussion about how to preserve a global commons.

Antje Scharenberg: Another key feature of Europe and the USA’s colonial/settlement history is that the ocean became a space of racism, enslavement and colonial violence, starting with the Middle Passage. This history of racism and violence continues today, as European nation states have turned the Mediterranean Sea into the world’s deadliest border. A lot of really fascinating works have come out on this topic in recent years. I’m thinking here of the work of scholars and writers like Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake or Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (see Soundings 78 for an extract from this book).4

Marcus Rediker writes about the slave ship as one of the key technologies enabling the transatlantic slave trade and the workings of colonial capitalism.5 As well as pointing to the colonial and racist violence that runs through the history of modern seafaring, these works also show how the ocean can produce new political subjects on the transnational level. Recent works highlight what have been called – inspired by Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic from 1993 – the Black Mediterranean and the Black Pacific.6 In Pasifika Black, Quito Swan discusses the development of Black international resistance across the Pacific Ocean, including the famous example of Pacific islanders resisting the colonial powers’ nuclear testing in their waters as part of the Nuclear Free Pacific campaign in the 1970s. This highlights the need for a third foundational pillar of ocean

justice besides the questions of the environment and equality – issues of racialisation and colonial violence must be at the heart of the struggle for ocean justice.

Chris Armstrong: Another interesting story that relates to this discussion is the story about the so-called ‘lascars’. When steamships were introduced, it really changed the nature of labour on ships – they went from being reliant on the labour of highly skilled sailors to being powered by a furnace that anyone could stoke. The shipping industry fairly quickly then shed all of the more highly paid European sailors and turned to Asian ‘firemen’ as they were called. The people doing this job then got called ‘lascars’, which meant something like ‘generic Asian’. Sometimes they’re Chinese, sometimes they’re Indian, but they just get called ‘lascars’, which is clearly an offensive and

derogatory term. But there’s also a sense in which ‘lascar’ becomes an identity around which people mobilise from below. Amitav Ghosh has written about this.7 While the life of a ‘lascar’ employed in the ocean was terrible in lots of ways, it also offered some people the opportunity to escape even worse conditions back home – and to find new kinds of pan-Asian and transnational solidarity. I like the idea of using the ocean as a crucible of new orders and political possibilities.

Antje Scharenberg: I’d like to finish on this note of resistance, and looking at some of the alternative visions of international politics that emerge at sea. In your book, you discuss in depth some of the legal debates that have led us to the way in which the ocean is legally constituted today; these largely go back to Hugo Grotius’s early seventeenth-century idea of the free sea, mare liberum, in which, simply put, more or less anything goes. But a space of freedom from rules can be interpreted in a number of different ways. In my own work I’m interested in thinking about how the ocean can look radically different if we consider alternative visions from below, and what it means for ocean activists to act politically in the international territory of the sea. There’s some fascinating historical examples, as discussed, for instance, in Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker’s The Many-Headed Hydra, which tells the history of the revolutionary Atlantic, populated by all sorts of radical actors throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.8 In the twentieth century, we may think of famous examples like Greenpeace’s campaign vessel, the Rainbow Warrior, as well as the global anti-whaling struggle, which ultimately led to a moratorium on commercial whaling that is still in place today. What’s interesting here is the ways in which new organisations emerged from this. For instance, Sea Shepherd emerged out of Greenpeace, precisely based on the realisation that ocean spaces needed specific attention within the wider environmental struggle. Today we see something similar happening with Ocean Rebellion, which is an offshoot of Extinction Rebellion, again set up precisely to be able to address ocean-specific issues more directly.

Chris Armstrong: Exactly, and that’s why I’ve become involved with Ocean Rebellion, and why I think it’s so important to create a public sphere for the ocean, which is what they are beginning to do. They’re trying to push ocean issues to the top of the political agenda very quickly. The reason I’m sympathetic towards Ocean Rebellion, as opposed to some of the other ocean-based NGOs, is that they’re absolutely prepared to say that ocean politics is just not working. That it’s completely dysfunctional. So there’s no sense of allegiance to the existing institutions, or any idea of tinkering with the existing institutions. Their perspective is that the existing institutions are what has gotten us here. They’ve failed. They’ve brought us to this predicament. This means that that one important task is to make sure that people making decisions within those organisations are named and pressured to do things differently. But – given that formal ocean politics as it is currently constituted is not doing its job of protection or dealing with spiralling inequality – we also need to think more creatively about what a subaltern ocean politics could look like, and how we could build that from the grassroots. It’s essentially a question of trying to fill that vacuum. It’s trying, within a very short timescale, to create what doesn’t exist, which is a route that links concerned citizens who care about environmental destruction to political

decision-making processes. It’s about trying, fairly directly, to act as a transmission mechanism between citizens and leaders, and to place pressure on them.

Antje Scharenberg: Another example of a direct action that had an immediate effect was Greenpeace dropping a boulder into the North Sea, which subsequently has had to be circumvented by fishing vessels, since their nets would otherwise get caught – this created a de facto marine protected area, with immediate effect! Direct action enabled Greenpeace to avoid the need for a much longer term legal struggle for a conservation area.

Chris Armstrong: What activists are doing here is exploiting the weakness of the legal framework, because it turns out to be the case that, whatever the British government may wish the legal situation to be, it isn’t actually illegal to drop boulders on the Dogger Bank. And this example also shows that there is a huge enforcement gap for international sea law. There are rules and regulations that are supposed to govern what happens on the high seas, for example, but they are rarely enforced. The states that allow ship owners to fly flags of convenience are absolutely uninterested in living up to their consequent responsibilities. There’s a nice correspondence here – the openness of the legal framework is what creates problems, but the same openness is what creates political opportunities.

Antje Scharenberg: Civil sea rescue is another example of a struggle which has become increasingly politicised in recent years, with the emergence of campaigns like Abolish Frontex. Here too, the legal framework is at issue – the international legal obligation to rescue people in distress at sea has become the subject of a hotly contested political struggle in the Mediterranean, because of the racialised dimension of European bordering practices. The interesting thing here is that a humanitarian obligation – rescuing people in distress at sea – has led to much more radical anti-racist visions, such as border abolitionism and, very practically, the demand to defund actors like Frontex. To me, one of the really fascinating questions is how to understand the nature of the types of transnational agency that are emerging here, in the ‘radical sea’. You call for the setting up of a World Ocean Authority as part of a strategy for radically altering the status quo of the ocean.

Chris Armstrong: I’m keenly aware that the response to this suggestion by the majority of people is that this is not going to happen – and this applies especially to people in the legal community and the policy community. But questions about the practical possibility or otherwise of ever setting up such an agency are not the ones I’m trying to answer with this suggestion. The question I’m trying to answer, given that what exists has comprehensively failed, is what a solution would look like – whether it’s likely to happen or not. That’s a question that utopian politics is always concerned with, and this way of thinking about issues is completely indispensable. So we may not know

how to get there, but we have to be able to orient ourselves through a vision of what a just world would look like. It’s about pulling a switch, calling for a break: it’s about asking the question – given that we’ve treated the ocean as a rubbish bin and as a place from which we can take and take without any consequences, and that we know that this framing is completely misplaced – of what an alternative framing would look like, one that actually involves justice for the oceans as well as the planet.

Interestingly, one of the best ways of protecting the ocean would be to do nothing to it, because our knowledge of ocean ecosystems is highly limited. We don’t want another instance of the hubris of the Anthropocene – the assumption that we can design the kind of ocean that we want. By and large, all we need to do is to radically downscale the industrial demands we put on the ocean, and this includes putting an end to the extreme extractivism of activities like industrial fishing, and putting a ban on seabed mining. Of course there’s a down side to that, which is that it involves recognising that the ocean is not a treasure house where we can find funds for redistribution – which was the idea of the new international economic order, as we discussed earlier. To some extent we have to distance ourselves from that idea, in favour of a different model of collective responsibility towards the future – to the animals and the other creatures that live in the ocean, and to each other: we need to start to nurture this enormous ecosystem. It’s a challenging thought, but such a challenge is necessary. We have to think about a different kind of end game – which wouldn’t be an ending but would open the way to a different long-term future.

To come back to the idea of a radical sea – it is also imperative to think about the land and the ocean at the same time, because they stand in relation to one another. The idea of the ocean as a resource frontier, for instance, implies that we will never really have to deal with issues of sustainability or environmental protection, because there will always be another set of resources that we can access. At the moment it looks as if that’s the role that the ocean is playing for some of us. We tell ourselves there’s always going to be minerals in the ocean so we don’t need to deal with the problem facing us now. It’s a way of deflecting claims that we need to reduce our exploitation of the planet, reduce our consumption. In this mindset, we will always have further frontiers – and, after the ocean, the next frontier will be space of course. There’s two, linked, dangers here: the first danger of continuing to exploit the ocean is that we destroy its ecosystems. But the second danger is that relying on the exploitation of the ocean allows us to not face questions back on dry land about environmental destruction, or equality, or what our economy should look like. It’s no accident that we’re always looking for this next frontier – it’s a way of endlessly deferring the task of attending to both of the crises we face, environmental

destruction and inequality.

L. Khalili, Sinews of war and trade: Shipping and capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula, Verso 2020; L. Campling and A. Colás, Capitalism and the sea: The maritime factor in the making of the modern world, Verso 2021.

M. Dalla Costa and M. Chilese, Our mother ocean: Enclosure, commons, and the global fishermen’s movement, Common Notions 2014.

A. Getachew, Worldmaking after empire: The rise and fall of self-determination, Princeton University Press 2019. Getachew talked to Ash Ghadiali about her book in ‘World makers of the Black Atlantic: Adom Getachew talks to Ashish Ghadiali’, Soundings 75: https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/soundings/vol-2020-issue-75/abstract-7660/.

C.E. Sharpe, In the wake: On Blackness and being, Duke University Press 2016; A.P. Gumbs, Undrowned: Black feminist lessons from marine mammals, AK Press 2020. For an extra from this book see Soundings 78: https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/soundings/vol-2021-issue-78/abstract-9413/.

M. Rediker, The slave ship: A human history, Viking 2007.

P. Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, Harvard University Press 1993; The Black Mediterranean Collective (eds), The Black Mediterranean: Bodies, borders and citizenship, Palgrave Macmillan 2021; Q. Swan, Pasifika Black: Oceania, anti-colonialism, and the African world, New York University Press 2022.

A. Ghosh, Sea of poppies, John Murray 2008.

P. Linebaugh and M. Rediker, The many-headed hydra: Sailors, slaves, commoners, and the hidden history of the revolutionary Atlantic, Beacon Press 2013.

Published 26 June 2023

Original in English

First published by Soundings 83/2023

Contributed by Soundings © Antje Scharenberg / Chris Armstrong / Soundings / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Despite Lithuania’s Europeanism, its policies on LGBTQ rights are sometimes closer to Russia’s. At the end of 2023, the Lithuanian parliament voted against amending the country’s notorious ‘gay propaganda’ law, in defiance of the European Court of Human Rights.

The US Supreme Court has overturned two landmark cases that protected a woman’s rights over her own body for 50 years. How did ‘fetal politics’ — a political movement that has turned embryos and fetuses into ‘unborn children’ endowed with unique and inviolable civil rights – gain such momentum? And what will be the outcome of this new ruling?