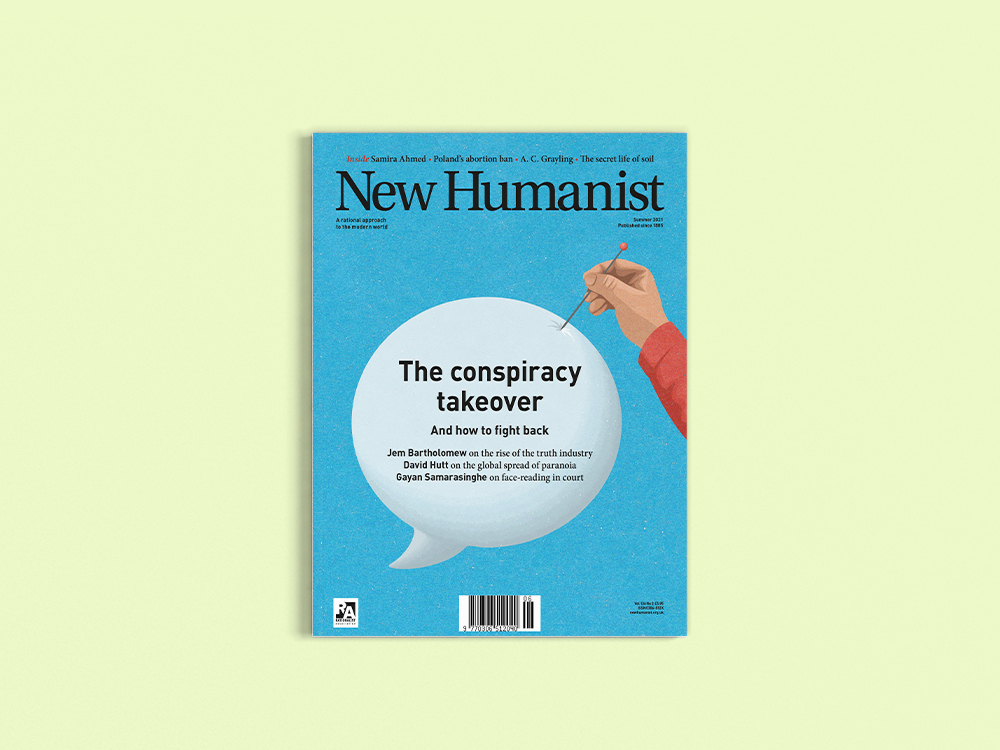

Conspiracy theories lead ‘New Humanist’ to consider the universality of thought across countries, cultures and time, and the speed of fact-checking versus disinformation. Also: questionable courtroom practices based on what judges see rather than hear.

New Humanist takes issue with the perceived decline of truth and efforts to re-establish its standing – both online and in court. Since Oxford Dictionaries named ‘post-truth’ their word of the year in the wake of Brexit and Trump, ‘the idea that we are living in a “post-truth” era has itself become mundane,’ garnering nothing but a ‘collective shrug of the shoulders’, notes editor Samira Shackle. But has there ever been an era when truth and veracity have prevailed as the discourse on post-truth seems to implicitly suggest?

Seeking a convincing answer, David Hutt breaks down the analyses of conspiracy thinking into two current positions, the relativist and the universalist, espousing aspects of both. Relativists have a point when they say that conspiracies are context-specific, but they fail to account for the cross-cutting nature of paranoid thinking. ‘What if conspiracy theorising is not just universal across all countries and cultures but also ever-present across time, a defect of human thinking that won’t disappear … ?’, Hutt asks.

If this is the case, all that remains is to learn to live with conspiracy theories, trying to distinguish between those that serve the powerful and those that, though false, rise from below, expressing ‘scepticism of those in power, and the questioning of received wisdom’, concludes Hutt.

Fact-checking

As conspiracies threaten the social bond, an ever-expanding online army is at work stemming their most harmful consequences. Fact-checking organizations have nearly quintupled in the span of a decade; for-profit, non-profit companies, charities and research institutes all add up to the flourishing anti-misinformation industry. ‘Today the ecosystem tracking misinformation is a rich neural network firing on all synapses’, writes Jem Bartholomew.

Yet the success of anti-misinformation efforts doesn’t go unquestioned: some say fact-checking doesn’t spread as easily as disinformation, or believe that for-profit tech companies can be no solution to the information crisis, as they are part of the problem. Finally, ‘the wider argument critics make … is that it attacks symptoms not causes: the inability of social media companies to get a grip on misinformation … and the unwillingness of governments to regulate them.’

In court

Overturning a previous decision, a senior judge in Britain refused to hold a virtual trial, arguing that the postage stamp version of the defendant on Skype was too small. The ruling unwittingly shed light on a widespread practice in courtrooms: the assessment of outward appearance and body language to ascertain truth.

Cesare Lombroso’s nineteenth century physiognomy, postulating a correlation between appearance and character traits, is now seen as pseudo-science, but faith in our ability to read secrets in changing facial expressions lives on. ‘What happens when judges themselves believe that there is a common standard of demeanour for honest witnesses or for “real” victims?’, asks barrister Gayan Samarasinghe. Efforts to read demeanour in court often remain unspoken, but, as forensic psychology has shown, they often result in discrimination targeting ethnic groups.

Read Samarasinghe’s piece in Eurozine.

This article is part of the 11/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 2 August 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Why abortion alone does not make women free

Claire Potter in conversation with historian Felicia Kornbluh

Last year’s overturning of Roe v. Wade took abortion laws in the US back to the nineteenth century. But despite the enormity of the setback, the moment provides pro-choice campaigners in the US with an opportunity to widen their political aims.

Despite Lithuania’s Europeanism, its policies on LGBTQ rights are sometimes closer to Russia’s. At the end of 2023, the Lithuanian parliament voted against amending the country’s notorious ‘gay propaganda’ law, in defiance of the European Court of Human Rights.