In times of war, art is a source of testimony and helps deal with trauma. Tragic events that are too close in time and space, however, can hinder inspiration and raise moral questions on artistic manipulation.

Ukrainian author and filmmaker Iryna Tsilyk talked with Agnieszka Holland, Polish director and screenwriter, for PEN Ukraine’s #DialoguesOnWar. This is an edited transcription of key moments from their conversation. You can check out the recorded conversation here.

Agnieszka Holland: I first met you, Iryna, during the Cannes Film Festival in May. We spent ten days together on the documentary jury. You came there directly from war-torn Kyiv with your son. We were walking on red carpets every day, drinking champagne. When I was watching you, I had the impression that you were unable to fully enjoy the experience, because your head and your heart were in another place.

Iryna Tsilyk: You are right. It felt very surreal, very weird. It was the first time I left Ukraine since the full-scale invasion started, and I immediately dove into this world of diamonds, chic red carpets, and careless people. My son and I came to Cannes directly from Kyiv. I thought we were not traumatized, but we were. I had a panic attack during the screening of Top gun: maverick when I saw planes performing an air show in the sky.

During the first eight years of the war, I actively took part in everything related to the topic. I was drawn as a magnet to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. It may seem like I was hunting for a ‘hot’ topic or a special plot. This is not true. The fact is that it was impossible to live my normal life in peaceful Kyiv and avoid the realization that the war was going on in the East of Ukraine. I used every chance to go there, meet people, listen to their stories and tell them to others.

I shot two short documentaries about women defending Ukraine for the Invisible battalion project. I made films about the famous Ukrainian paramedic Taira and stormtrooper Andriana Susak, also known as ‘Kid’. Earlier this year, Taira was captured by the Russians. Fortunately, she was later released.

The earth is blue as an orange was my attempt to understand what it means to be a civilian in a war zone. I felt huge empathy for my characters, Hanna and her four children, who lived in the war zone and tried to live to the fullest despite everything. When the full-scale Russian invasion started, when the war came to Kyiv, I got a chance to step into my characters’ shoes, and I suddenly found myself speechless and powerless. I still feel very confused and imbalanced. For us artists and filmmakers who try to observe other people’s lives, it is important to have some distance between us and our characters, our stories. When we are in the epicentre of the events, it is impossible to look at the situation from above.

Agnieszka Holland: Serhiy Zhadan, a great Ukrainian writer and poet who recently came to Poland, said in an interview the same thing you are saying now: he does not have any need or motivation to write poetry. Your case, however, is different. Now that women are active and are taking real responsibility in this war, describing and expressing their experiences is extremely important. But I understand that it may be difficult for you to do it right now.

Iryna Tsilyk: A lot depends on the tools we use in art. Some arts have the magic power to capture the ‘here-and-now’. Poetry, in my opinion, is one of the most magical tools, and it is a pity that Zhadan cannot write anything at the moment. But some poets can, and they create fantastic things trying to grab the moment, to stop it, to reflect on all the factors that change us today. We do change extremely fast, and this metamorphosis is very important to document.

Authors who write novels and directors who create fiction movies need distance when approaching a topic like war. It is difficult to be objective when you see the situation in a close-up. You need to look at it through a wide shot, which is impossible if you are in the epicentre of the events.

During all these years, I was constantly trying to find answers to the question: does art have power in times of war? In The earth is blue as an orange, my characters were shooting amateur films about their lives during the war. For them, it was a way to deal with trauma. By re-enacting some traumatizing experiences from the past, they had a chance to look at those experiences through different optics. While I was simply an observer, I believed that mattered the most. Everything changed when I stepped into my character’s shoes. I became that mother watching her child physically shaking because of fear.

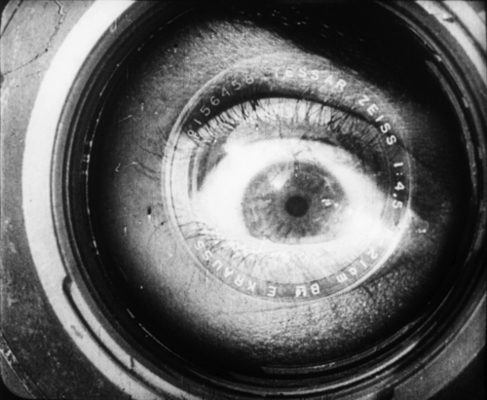

Frame from Dziga Vertov’s documentary Man with a movie camera (1929). Via Wikimedia Commons.

I am also afraid that some cinematographic tools may lead to crossing the very thin moral line and making art on blood. I have received many requests from foreign production companies who offered me ideas and scripts about war events that are currently happening or have happened very recently, such as Bucha and Azovstal. In my opinion, it is too early and dangerous to go down this road. It is like a minefield. It is so easy to make a mistake. People are still being tortured, raped, and held captive. It is not the right time for shooting fiction films where atrocities happened. Yet I often ask myself: as an artist, should I just grab my camera and document the reality?

Agnieszka Holland: I do not think there are rules. It is very subjective. Documentary cinema is necessary. It documents atrocities, among other things, and can be used to bring perpetrators to justice. You are correct about fiction though: it does require a distance of time and place to be capable to tell a story.

When I analyzed literature written during World War II in the concentration camps and ghettos in occupied Poland, I found that the fiction novel as a genre was absent among those pieces of writing. By the end of the war, some powerful short stories started to appear, along with poetry and diaries. These genres were best suited to capture and pass the experience on. Fiction is heavy. It is always some kind of manipulation. And you feel like you do not have the moral right to manipulate the suffering. These stories have to be very naked and raw.

I am afraid, however, that no one will be interested in watching things like that. During these last eight years, since the Revolution of Dignity, Ukrainian cinema has become one of the most powerful in Europe. And probably the only one speaking about very important things. But based on my own experience, it is difficult to find interest in something political, something unpleasant. Cinema has become very escapist. Securing funding to make a movie about love or family relations is much easier.

Iryna Tsilyk: I, on the other hand, am afraid of becoming hostage to this topic. I feel like my colleagues and I need to make films about the war. Since 2014, the world first expected war movies from us, then it got tired of it, and everyone was expecting films about the war but without the war. The earth is blue as an orange is not about the war itself, but about people and universal things like love, art, friendship, and family. I wanted to change my focus and shoot something else. And once again, I found myself unable to do so because the reality around me is so much stronger than anything else.

Recently, I have started to come back to myself. At the moment, I am working on a new project. I want to make an animated documentary, which is a completely new genre for me. In my opinion, this is one of the strongest and most sincere ways to talk about personal stuff. Especially things that have already happened to me, my family, or the people I know. I do not want to shoot any reconstructions.

As a woman, I want to talk about the feeling of insecurity, which I currently share with all the women I know. We are facing so many fears. I also feel like there are many crossroads and connections between our experience and that of women from the past, my grandmothers and their mothers. History goes around in circles, again and again. All the trauma from the past, the trauma of the previous generations, is still here. We still need to face it.

Published 26 October 2022

Original in English

First published by Eurozine (edited transcript)

Contributed by PEN Ukraine © Iryna Tsilyk / Agnieszka Holland / PEN Ukraine / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

Mineral rush

Topical: Critical raw materials

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.