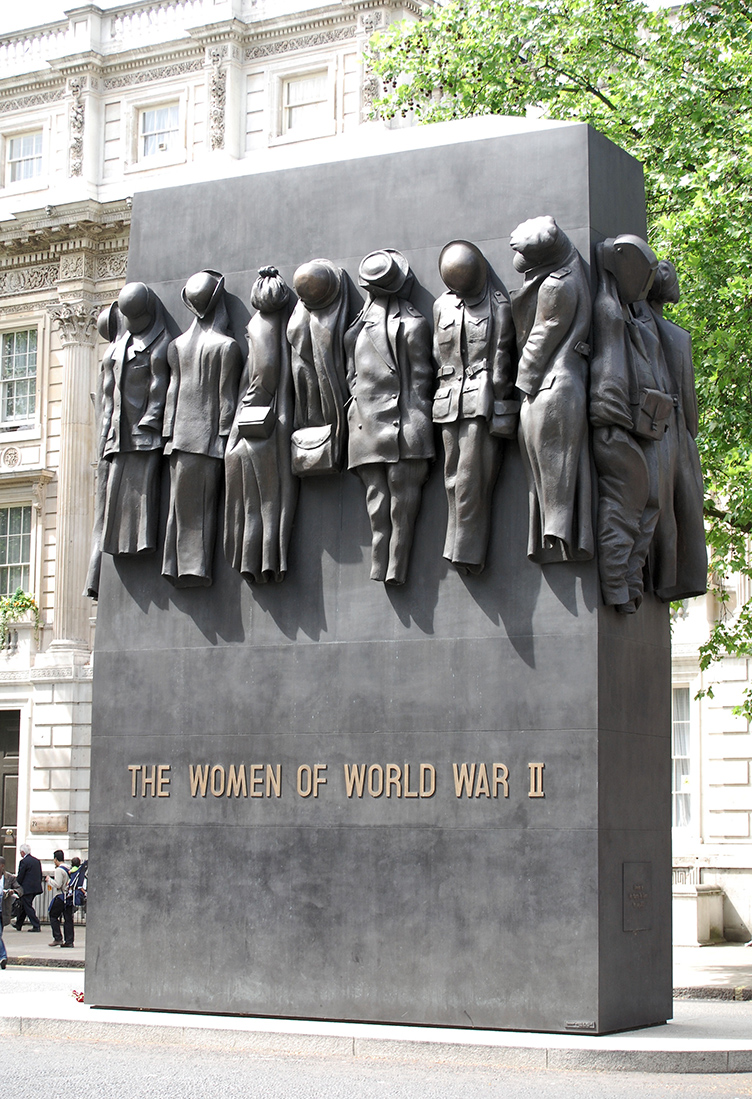

Photo via Pikist

I’ve often wondered about commemorations, the sense of gatherings like this one. Do we commemorate because tradition dictates that we do or is there more to it than that?

Last spring, while giving a reading on Marga Minco’s work and the war – I don’t know whether the war is stalking me or I’m stalking the war – I remarked that commemoration should be more than a ritual, that it should bear within itself a desire for knowledge and, therefore, that clichés are the enemy of meaningful rituals of commemoration. I also realized that the other cliché, which suggests we already know the story of the war and the Jews well enough by now, has grown louder and louder; this arrogant cliché is based on the idea that our knowledge is complete and we can free ourselves from the relatively recent past.

Saying that one knows the past well enough by now usually amounts to a refusal to get to know that past. And those who do not know the past are not so much doomed to repeat it as doomed not to know who they are. Nothing makes people long for a cut-and-dried identity more than the gnawing suspicion that they have no idea who they are. And it is often the cut-and-dried identity, the refusal to deal playfully with that identity, that results in the Other being seen as a complete stranger and absolute nemesis.

After the Minco reading, a psychotherapist came up to me. She said that we need rituals and clichés to keep commemoration from making us ill, that we need to keep the past at arm’s length in order not to have it drag us down. Certainly. But, if the twentieth century does not make us feel ill at all, I fear that nothing has been remembered and even less has been understood. Not feeling ill could very well be a symptom of looking the other way, of denial. If we claim that the sicknesses of the last century, of industrialized totalitarianism, of antisemitism erupting into genocide, of biological racism, are not deeply rooted within our culture, then we do not know who we are. And it is precisely then that we are most susceptible to seducers who arrive to tell us who we are and whom we should fear.

Commemoration is also a way to indicate who it is you wish not to be, yet who you fear you could nevertheless become. No commemoration exists without this fearful suspicion, at least no meaningful commemoration without the reasonable fear that we are the future culprits and their helpers.

Commemoration is based on the conclusion that the past is not finished yet, on the realization that the womb which bore the Third Reich is not yet barren.

Censorship and banishment are no answer to that fecundity; living in a country where the government does not tell us what virtuous thinking is and what it is not is true attainment. However, this does not mean that every line is there for the crossing. It is for good reason that certain taboos have gradually become lodged in our culture since 1945; breaking a taboo is not always liberating, sometimes it is merely a relapse.

This commemoration is always a warning as well.

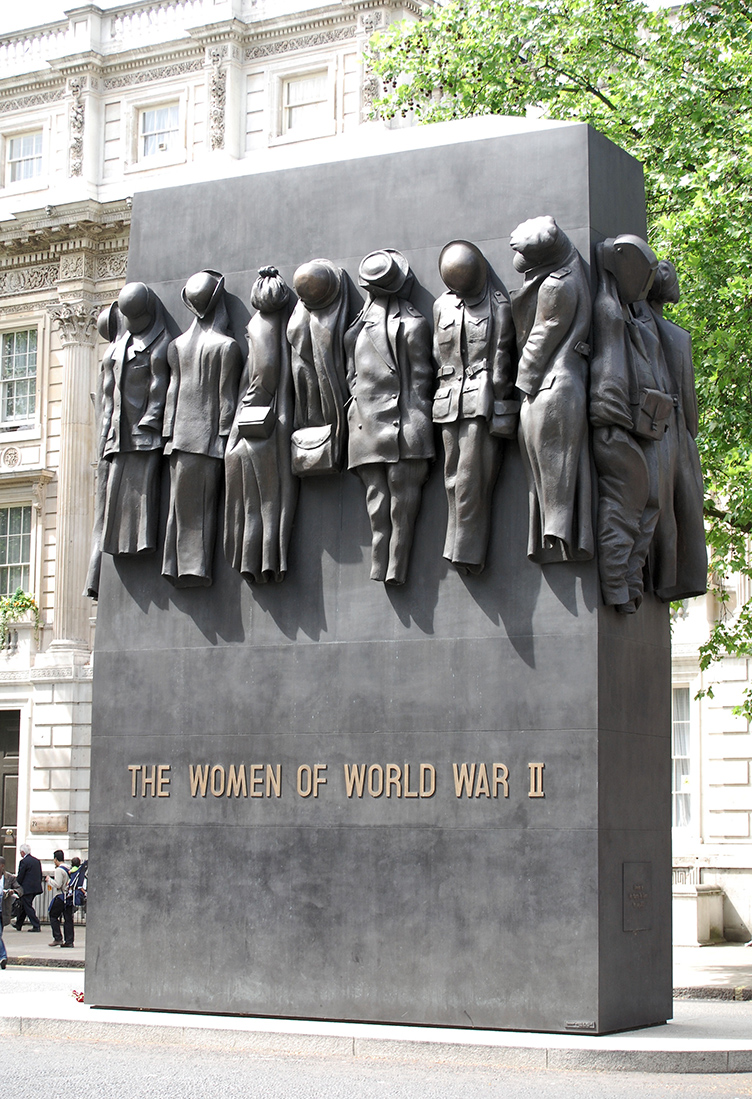

Photo by Illustratedjc / CC BY-SA from Wikimedia Commons

The story of survivors, of those who returned from concentration camps – Jews, Roma and Sinti, political dissidents, including many communists and social-democrats – is a story of exceptions. Most victims only ‘left’ the camps through the chimneys. My mother was one of those exceptions; her parents, my grandparents, were not.

To commemorate, at the same time, is to speak on behalf of the dead, and one can only speak on their behalf by allowing those who were there bear witness. So allow me, if you would, to cite an eyewitness who was very close to the dead: Filip Müller, a Slovakian Jew and member of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Sonderkommando unit workers, who were mostly Jews, were charged with removing corpses from gas chambers, cutting their hair, pulling out their gold teeth and burning the bodies. Most members of the units were murdered themselves after only a few months. The last Sonderkommando at Auschwitz staged a rebellion in the fall of 1944, and almost all of its members were killed. In his memoirs, Müller tells of a group of Jewish families who had been hiding in miserable conditions in bunkers close to the Polish town of Sosnowiec. It was their children’s crying that led the SS to them.

They were taken to Auschwitz. The women and children were told to undress, as was usual procedure. However, unusually, they were not led to the gas chamber but executed on the spot. Müller does not explain why. Perhaps there weren’t enough people right then to fill the gas chamber. Perhaps Zyklon B was too precious to waste; the Nazi killing machine, in addition to all other aspects, was an economic affair, a gigantic plunder in which the killing and removal of bodies took place with all due efficiency.

The naked women and their children were lined up against the wall. Then Müller writes of a woman with her baby in her arms: ‘Voss, the executioner, was walking around them nervously with his small caliber rifle, trying to find a suitable spot on the child’s body to point his gun. When the despairing mother realized this, she twisted and turned every which way to shield her child from the line of fire. She tried desperately to cover every spot on her child’s body with her hands and arms. Then, shots suddenly rang out in the silence. The child had been struck in the side of the chest. The mother, feeling her baby’s blood running down her body, lost self-control and threw the infant in the murderer’s face, after he had already aimed his rifle at her. Senior squad leader Voss was stunned. He stood nailed to the spot. When he felt the blood, still warm, on his face he lowered his rifle and wiped it away with his hand.’

It is telling to note that today we know the squad leader’s name but not those of the woman and child, and we probably never will.

Photo via Pxhere – CC0 Public Domain

If commemorating is also a desire for knowledge, then details are crucial. Knowledge consists of details; therefore, we cannot permit ourselves to say that there are some details we don’t want to hear because they come back to haunt us in our sleep.

Before this woman threw her dying baby into squad leader Voss’s face, there were elections, administrative directives, willing and less willing helpers, most of whom had never visited a concentration camp, never killed anyone. It is good to note that after the war it was not only the Germans who said they knew nothing about the whole thing, that they were only following orders.

In Persecution, Extermination, Literature, professor of comparative literature S. Dresden writes about an incident mentioned by the author K. Tsetnik, the pseudonym of Yehiel De-Nur. The crematoriums at Auschwitz were overloaded, and so a group of gypsy women and children were thrown alive into a pit. A Dutch prisoner was ordered to pour kerosene over them. When he refused, he was kicked into the flames himself. ‘The Dutch “Nee! Nee!” (“No! No!”) was obviously still ringing in the writer’s ears’, Dresden notes.

My mother arrived in Auschwitz in the autumn of 1944, shortly after the Sonderkommando revolt, of which she knew nothing. She herself said she was happy in Auschwitz, because she had hope there; she only lost that hope after the liberation, when the true extent of the catastrophe became clear.

She was born in Berlin in 1927 and had travelled with her parents onboard the notorious S.S. St. Louis in 1939 from Hamburg to Cuba. But Cuba, the United States and Canada had closed their borders, and so she and her parents were washed ashore in the Netherlands.

My father, born in 1912, also in Berlin, survived the war by hiding at various addresses. He often had to pretend to be a deserter from the Wehrmacht in order to be given a place. He talked little about himself and, when he did, it was more or less by accident, in passing. However, one of the people who gave him a hiding place apparently said to him after the war: ‘If we had known you were a Jew, we would never have taken you in.’ He stayed in contact with a family in Rotterdam who had given him shelter. Once a year, he would take me to visit them. They kept white mice in a cage.

Then there was the herring vendor whose cart was close to the stock exchange on Rokin in Amsterdam. Even though we lived on the far south side of town, my father always took the number twenty-five tram to Rokin because he knew the man from the war. The herring vendor had been in the resistance. I went with him sometimes and, although they must have known each other well from back then, they never really talked about anything other than herring.

That was the war to me as a child: white mice in a cage, a herring vendor in front of the stock exchange, the happiness of Auschwitz.

Back then I never thought that a few decades later, as a columnist for a Dutch newspaper, I would receive a series of shamelessly anti-Semitic emails. Back then I still thought that the taboo was too great. That was naive.

And it’s also logical that, when certain segments of the population are talked about in a way that hearkens back to the darkest years of the twentieth century, sooner or later people will feel empowered to talk about Jews in the same way.

For me, it was clear from the start: when they talk about Moroccans, they’re talking about me.

‘I can’t understand, cannot tolerate it when a person judges another person not by what he is, but by the group to which he happens to belong’, Primo Levi wrote to his German translator in the 1960s.

These are words we should repeat to ourselves on a weekly, perhaps even daily, basis if only to remind ourselves how toxic words can be. The fate of a Dutchman at Auschwitz who was forced to pour kerosene over living women and children began with words, with speeches by politicians. In these secularized times in particular, I believe that members of parliament and government ministers bear extra responsibility to set a good example, to make sure the word does not become poison, to keep in mind at all times that the state is both a necessary thing and a potential evil capable of heedlessly, nonchalantly pulverizing whole sections of the population.

The woman who threw her dying child in the face of senior squad leader Voss warns us.

The Dutchman who shouted ‘Nee! Nee!’ as he refused to pour kerosene over living women and children and was then kicked into the flames himself warns us.

Photo via Pikist

Arnon Grunberg’s lecture, commissioned by the Nationaal Comité 4 en 5 mei on the occasion of 75 years of freedom in The Netherlands, was delivered on Dutch WWII Remembrance Day, 4 May 2020. The Dutch Foundation for Literature commissioned its English translation.