'It’s important to be open'

A Knowledgeable Youth podcast

Remaining in a new country or returning home? The Knowledgeable Youth podcast delves into the complex decision-making refugees face when migrating, together with researcher Olena Yermakova.

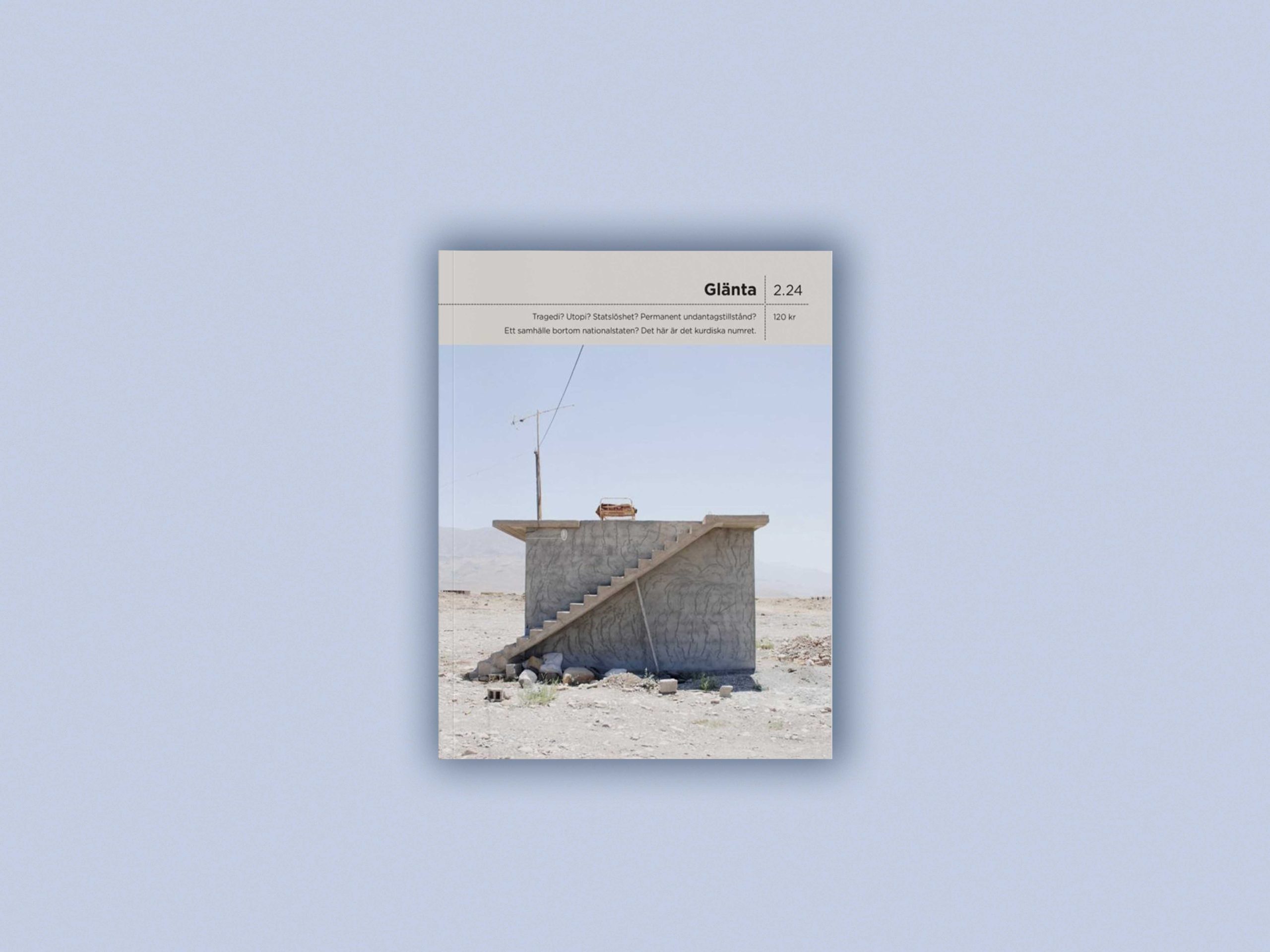

On the past, present and future of Kurdistan: rethinking power structures; statelessness in a world of states; and Kurdistan as a war laboratory.

Glänta’s recent issue gathers reflections on historic and present Kurdish identity. Guest editor and Swedish-Kurdish author Agri Ismaïl writes: ‘In the absence of the overarching narrative that a nation state provides to its people – the shared story of a country – Kurds have struggled to form a unified identity.’

Elif Sarican presents a historical overview of the Kurdish people, outlining significant political developments that have impacted the population’s changing identity. Referencing the twentieth-century research of anthropologists Edmund Leach and Fredrik Barth, Sarican writes that Kurdish identity can be understood as ‘dynamic, capable of adapting to changing circumstances.’

Simultaneously, ‘a more essentialist view of ethnicity’ also unifies the Kurdish people. And ‘embracing both fluid and fixed notions of identity’, while seemingly contradictory, enables a dispersed society to ‘resist assimilation’ and ‘fight for existence and recognition’, writes Sarican.

The Kurdish Freedom Movement, which Sarican describes as an alternative to the US and UK-supported Kurdistan Regional Government, reflects this non-conformist, resistant tendency. Positioning women’s liberation centrally, the movement aims to redress the patriarchy entrenched within Kurdish society. Independent decision-making bodies for women that can veto mixed-gender forums are reflective of an ideology that opposes hegemonic power structures.

The KFM moves beyond the limits of the traditional nation, with the potential of inviting the rest of the world to rethink power, argues Sarican: ‘the spirit of Kurdistan – the spirit of freedom and self-determination – has the potential to flourish far beyond the geographical borders of historic Kurdistan.’

Barzoo Eliassi writes on the bitter realities of being stateless in a world of nations. His research, from a background in social work, focuses on theories of identity and belonging presented alongside testimonies from the Kurdish diaspora.

As Kurds are often registered as Turkish, Iranian, Iraqi or Syrian, the population is difficult to track, both today and historically. Kurdish migration to Europe began in the 1960s, due to warfare in the Middle East, waged from all sides, and the European demand for migrant workers. Eliassi argues this large-scale migration was crucial for setting the foundations of a politicized Kurdish identity: the ‘Kurdish question’ evolved into an issue of ‘transnational character’. However, Kurds who protest in Sweden today, calling for recognition from politicians, remain unheard.

Eliassi connects this lack of international recognition to Jill Stauffer’s term: ‘ethical loneliness’: a form of social abandonment caused by the inability of nations to include stateless peoples. The European left’s lack of knowledge of the suppression against Kurds in the Middle East demonstrates this isolation. ‘In the Muslim world, Kurdish demands for self-rule are seen as an imperialist or Zionist attempt to undermine the imagined social cohesion of states where Kurds are subordinated to Arab, Turkish and Persian dominations,’ writes Eliassi.

As a nine year old following CNN’s broadcast of the Gulf War, Agri Ismaïl recognized James Earl Jones’ voice as that of Darth Vader, used to announce ‘This is CNN’ between news features. Jones’ presence, writes Ismaïl, added a cinematic effect to the media coverage, which already portrayed the war as ‘reality-TV’, conveying a sense of the American army’s superiority. ‘The technological advantage was so enormous that the war could hardly be said to have taken place – this ultra-modern war was won in advance’.

Ismaïl describes Kurdistan as a test site for war technologies. Saddam Hussein’s regime tested missiles and chemical weapons that lacked sufficient precision for war, terrifying Kurdish populations. During the Iran-Iraq war, millions of highly advanced landmines, manufactured in Italy, were planted on Kurdish land. Today ‘entire fields are covered by small red triangles that have been put up by the UN’s Iraq Mine Action Program – warning signs that the earth no longer belongs to us but has been conquered by machines’, writes Ismaïl.

The idea of Kurdistan as a borderland, open for war experimentation, derives from the outside world’s dehumanizing tendency towards Kurdistan, and Kurds being portrayed as an uncivilized, barbaric population, argues Ismaïl. But what goes around comes around: as Aimé Césaire and Michel Foucault identified, colonies are merely a testing ground before technology is used by colonizers on their own people. Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles, developed by the US army during the Iraq War, can now be found stationed at American law enforcement agencies.

Review by Märta Bonde

Published 11 December 2024

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Remaining in a new country or returning home? The Knowledgeable Youth podcast delves into the complex decision-making refugees face when migrating, together with researcher Olena Yermakova.

The technological link between the rifle and the film camera, the medial links between the Gulf War and Star Wars, the colonial history of bombs – piecing together historical and contemporary fragments reveals an image of Kurdistan as a testing ground for military technology unleashed without responsibility for its consequences.