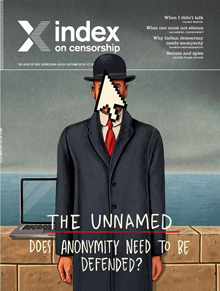

This article is a highlight from, which includes a special report on anonymity. Cover artwork: Ben Jennings.

On 7 October 2006, journalist Anna Politkovskaya was murdered in Moscow. Ten years on, the battle to publish investigative journalism in Russia is still being lost.

When Polikovskaya died, there was speculation of government involvement, an international outcry and various posthumous awards for her investigative work. Yet in Russia there was no scandal, no mass protests. She was mostly deemed a “crazy loner”, one of a very rare breed of reporters who believed in press independence.

A decade later, we have a better understanding of Politkovskaya’s significance for Russian journalism. Like many of her generation, she was a product of the perestroika years of 1985-91, and remained faithful to its ideals in the years that followed, when a majority of her colleagues “tired of freedom”. In the twenty-five years after perestroika, neither freedom of speech nor other political freedoms have been much prized by the majority of citizens of this new Russia.

In the 2000s, Politkovskaya’s stance was regarded as extreme. Who was there to fight against anyway? For what? The years of plenty were at their peak. Sooner or later economics would win and everything would sort itself out. Even liberals believed that.

It is important to understand the tradition to which Anna belonged. For her, being a journalist meant serving society, a tradition of self-sacrifice dating back to the nineteenth-century Russian intelligentsia. In the Soviet period, this tradition was inherited by dissidents. In Russia, the line between journalism and social activism remains blurred, and not because Russian journalists are unprofessional, but because independence of the press has remained the ideal of rare characters such as Politkovskaya. There is no long-standing tradition of media independence. Each generation of journalists instinctively chooses between fusing completely with the state, which means producing propaganda and giving loyal support, or remaining steadfastly professional and inwardly dissident. Working as a journalist in Russia is not so much pursuing a profession as living an ethical, existential choice.

Politkovskaya worked as an investigative journalist for Novaya Gazeta. Founded in 1994, Novaya Gazeta is probably the only publication that has consistently practised investigative journalism from the outset. Since 2000, more journalists and staff from Novaya Gazeta have been murdered than from any other publication: Yury Schekochikhin, Igor Domnikov, Anna Politkovskaya, Anastasia Baburova, Stanislav Markelov, Natalia Estemirova and others. The Russian-language New Times magazine, edited by Yevgenia Albats, also remains true to the investigative genre, as did, until recently, the media group RBC. From 2014, RBC published a succession of high-profile investigations into the activities of major companies, top-ranking Kremlin officials and their relatives. But, on 13 May 2016, the group’s editor Yelizaveta Osetinskaya and others were fired after reports of Kremlin pressure on the group’s holding company Onexim and RBC’s management.

Investigative journalism had already disappeared from other publications. It is expensive as well as dangerous. Investigation is labour-intensive, it calls for a large team and takes a lot of time. The speed of modern media obliges editors to churn out instant copy. That, however, is not the main reason why there are so few investigations in the Russian media. And the disbanding of the top team at RBC after it launched a series of investigations into senior state officials sent a signal to other media.

However, most resonant investigations of recent years have not been the work of journalists, but of politicians of one kind or another. The flagship of investigative journalism in Russia remains the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), a non-profit organization created in 2011 by the opposition activist Alexey Navalny. It conducts the most high-profile investigations of corrupt senior officials, and they are carried out by a highly professional investigative team of 20 to 30 lawyers, specialists and volunteers.

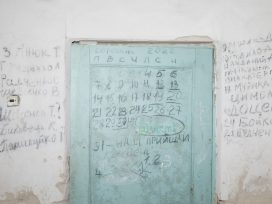

Similarly, the first person to write in 2014 about the secret funerals of Russian paratroopers when the military conflict in the Donbass region was escalating was Lev Shlosberg. Although Shlosberg publishes Pskovskaya Gazeta, he is primarily a politician.

We can also classify as journalistic investigative reporting, the 2008 document, “Putin: The Results – An Independent Expert Report” written by opposition politicians Boris Nemtsov and Vladimir Milov. The report described President Putin’s abuse of power and widespread corruption in government.

The paradox is that, in Russia today, no amount of scandalous revelations of corruption at the highest level sways public opinion. For most people, the findings remain unknown, because 80 per cent of the population get their news only from television.

TV aside, the most popular form of journalism in Russia today is the topical opinion column. Until the mass protests against Putin in 2012, it was thought that this, too, was defunct and that nobody was interested in the personal opinions of a journalist. Yet it was the columnists who, that year, restored journalism’s intellectual respectability by starting serious and engaging conversations about freedom and human rights. Many of them have since become important public figures.

In Russia, the side dish has become the main dish. Slon.ru, a business, economics and politics website founded in 2009, consists entirely of opinion pieces, which sometimes turn into mini-investigations, particularly when the author is Oleg Kashin.

Kashin is a good example of this new trend of favouring individual writers over newspapers – a trend which has grown largely thanks to social networks, especially Facebook and Twitter. Kashin showed the power of self-publishing by building the audience of his own website via social networks. Journalist and writer Arkady Babchenko, who carried out a one-man investigation into the shootings on Kiev’s Maidan Square in 2014, has the same approach.

This method is one way to survive, as journalists increasingly find it impossible to maintain an independent point of view while working for state owned, or even privately owned, media. What other ways are there? Besides the already well-established route of emigration from Russia to Ukraine, a route taken by Yevgeny Kiselyov, Savik Shuster, Matvey Gannpolsky, Ivan Yakovina and the recently murdered Pavel Sheremet, there are more exotic choices. The Medusa media portal, an independent Russian language socio-political network publication, is registered in Latvia. Galina Timchenko founded it in 2014, together with a group of former staff members, after she was sacked as editor-in-chief of Lenta.ru, the Moscow-based online newspaper.

Two processes are taking place in Russia almost simultaneously: restriction of free speech, and technological progress in the media sphere. This creates a strong sense of absurdity. Between 2008 and 2012, during the presidency of Dmitry Medvedev, there was a major breakthrough in new media technology, which coincided with the growth of the middle class. New standards were set, as demand rose for stories about politics, human rights, migrants and problems in society. This was seen not only by business publications like the daily Vedomosti, the liberal broadsheet Kommersant, and the Russian edition of Forbes, but also by cultural and listings magazines such as Afisha, which is now published mainly online, and Bolshoy Gorod, which closed down in 2013.

The complication of this scene culminated with the appearance of a new kind of publication, Openspace.ru, a news site for Russia’s creative vanguard, founded in 2008 by Maria Stepanova and Gleb Morev. Since 2013, the two partners have also been running the cultural magazine and news site Colta.ru. The internet seems to have given journalists more freedom and even made it possible to raise funds independently. A paid subscription scheme was successfully introduced for the first time by Slon.ru, who started their project by crowdfunding.

Before the 2012 protests, the Kremlin did not see internet publications as a threat: its total control of television ensured the loyalty of 70-80 per cent of the electorate. When Medvedev came to power, this balance even shifted slightly in favour of channels with smaller audiences. The Dozhd channel, dubbed “Television for intelligent people”, targeted the middle class and was founded in 2010. Part of Medvedev’s liberalisation project also included an independent and non-commercial public television channel (OTR), which he set in motion but which only started broadcasting in 2014.

It is significant that the main weapon of the “conservative restoration”, after Putin returned for a third term in 2012, was the traditional media of television and radio. There was not only a counter attack by those with anti-liberal values but also by the traditional media. Technology on its own proved inadequate for resisting the mechanisms of the state: that could be done only by people who had opinions.

In July, an enlightening conversation was leaked. RBC, now under new management after the previous staff were fired, held a meeting between management and journalists. One RBC reporter asked where the line should be drawn when reporting. Which topics, in other words, did the publication feel it could no longer cover? He received the answer: “That, unfortunately, nobody knows.” It is a response that encapsulates the predicament of the media in Russia which are trying to maintain a degree of freedom. It is a hole journalism has dug for itself.

Publishers and investors used to think that if they played by the rules and avoided open criticism of the Kremlin, no one would touch them. The rules are, however, constantly changing, and they aren’t written down anywhere. One can only second guess them. This Kafkaesque situation gives rise to a general sense of nervousness, but also tells us something about freedom of speech: anyone who voluntarily agrees to partial curtailment of their freedom will sooner or later have it taken away completely.

While resolving its practical problems by introducing new censorship laws, by emasculating leading information platforms such as Lenta.ru and the Russian-language news agency RIA-Novosti, by blocking such sites as Kasparov.ru and Polit.ru, and removing a number of editors-in-chief, the regime also accomplished a symbolic task. It managed to discredit the very notion of an independent press in the eyes of the general public. The conservative restoration in Russia since 2012 has been a struggle against anything that is “above” the state, specifically, against the idea of universal values and freedom of speech.

Most media have already lost the battle. Journalists have no experience of closing ranks to defend their rights, and most private owners are willing to abandon freedom of speech in order to retain their businesses. The disbanding of teams of journalists between 2013 and 2016 was generally explained away as being for commercial reasons: “the unviability of the publication”. Only in two cases did the Kremlin not get away with this ploy. The Dozhd television channel and the radio station Echo of Moscow put up a spirited all-round defence involving the editors, the staff, and the viewers or listeners. Amazingly enough, in both cases, the regime was unable to get them to abandon their critical stance.

The main target of government attacks in the future is likely to be the internet, with an attempt to take control of social networks. The recently adopted Yarovoy law increases the burden of responsibility for anyone whose internet postings could be deemed “extremist”, and obliges communications operators to keep recordings of all calls and messages, metadata, exchanged between users for six months. The same applies to internet service providers, who are obliged to keep metadata for three years. The presidential adviser on the internet industry, Herman Klimenko, appears to be considering the option of an autonomous Russian internet, analogous to that of China. “If we close our borders now, I mean virtually, all our sites will benefit,” he said in a recent interview with the BBC Russian service.

Under these conditions, journalism in Russia is often simply unable to perform the basic function of journalism, which is to inform the public about what is happening. Independent journalism does what it can, and by the very fact of its existence reminds people that alternative opinions about universal human values are possible. It provides an alternative to propaganda. The only good thing about the profession today is that people working in journalism are forced, much sooner than others, to make a moral choice where the line between good and evil is to be drawn.

Ten years after her murder, the example of Anna Politkovskaya is relevant to all of us.