Konrad Becker: One of the trajectories we tried to follow in the “Information as Reality” event in Linz was to look at what has happened in critical media cultures in the last twenty years; is there anything to learn from this that remains relevant today? As a starting point, the focus is on an understanding of the need for independent cultural production platforms but also on how the whole context for that changes in the current milieu of austerity. In the 1990s there was an explosion of independent cultural institutions, a movement in which all of us were involved. And so we thought we should maybe start back in the 1990s because then that was a clear thing. Everybody saw that we need new institutions to engage with cultural technologies; we need new labs and new platforms for discourse.

Felix Stalder: Perhaps we can begin by trying to remember what the thinking was during this wave in the mid-1990s, which led to the creation of platforms that involved or still involve Mute; here in Vienna: Public Netbase was part of this, just like de Waag in Amsterdam, and dozens of others across Europe. Suddenly there was this boom in platforms that were also networking with each other, but there was a clear idea that somehow cultural production needed new formats, new institutions. Maybe let’s start with that and try to resurrect some of the thinking that went into that. So why did that happen and what was the thinking?

Pauline van Mourik Broekman: In time terms our launch was practically simultaneous with yours, around 1994. I think the catalyst was this dissatisfaction with what was there, particularly in terms of the art infrastructure and system, the spaces. We were learning a lot from this phenomenon of artist-run spaces that had already been very important in London. However, in terms of publishing and the sort of discussion around art that was possible, it was politically quite impoverished and very much focused on individuals. That period saw the rise of the YBAs [Young British Artists] and the culture around the Internet, which we initially saw as coming more from America than from Europe, was incredibly energizing, even in its slightly crazy forms, such as Mondo2000. There was a kind of urgency to it that was completely lacking in the art debate.

In terms of what were to become the gathering places of critical Net culture, I remember that one of the first descriptions I read – I think it was of the first nettime gatherings – evoked this sense of how they functioned for people who did not really have a clear disciplinary home, or who lacked the desire to belong in a particular disciplinary or institutional context. These spaces enabled them to have new discussions, which makes sense to me. Of course they were also building on quite established cultural economies, like the electronic art festival circuit, which was very new for me at the time. I think that means we are talking about a bit of a hodgepodge of circumstances, which were maybe somehow fuelled by new strands of funding, particularly in Europe, which I don’t really have a very comprehensive grasp of, but which I think are quite important to acknowledge in that framing of what independent culture was.

Josephine Berry Slater: Obviously how I came to this was a little bit different than Pauline, because Pauline and Simon [Worthington] had taken the very bold step of actually establishing a magazine whereas I had just graduated from an MA programme and joined the magazine. For me, on a personal level, you could say it was more opportunistic rather than strategic, and was a happy accident in some ways. Maybe I just happened to fall into the right place at the right time, but I had been living in Berlin with Mizc Flor. He was working with people around the Kunstwerke. People like Pit Schultz [co-founder of nettime] were there, Mercedes Bunz and Diana McCarthy and so this dissatisfaction with institutions was very much within the arts, even inside the institutions. Kunstwerke spawned and attracted a lot of people who were also creating their own institutional experiments.

An almost kitsch form of self-institution was happening in a quite general way in the art world – for instance Christine Hill’s Volksboutique. Mizc Flor had converted his flat to use it intermittently as an independent arts and media space called luxus cont. Pauline and Simon came over to Berlin to show Mute for a week. They stayed there and did a series of events and talks and that is where I first came to know them. I met them in a self-institution and they had self-instituted as a magazine. I had just finished studying at the Courtauld Institute which is a very posh art institute in London, but even there we’d made our own magazine which was called Dr. No. Shortly after this Micz and I set up a very short-run magazine called Crash Media, which was all about creating feedback between print and online, and looking at new technologies and the way they were transforming cultures. Within that context we did a lot of interviews with people like Backspace and also Info-Centre in London, which was run by Jakob Jakobson and Henrietta Heise who went on to set up the Copenhagen Free University. All these issues were very much in the air; that’s clear. It was almost like something you didn’t have to think about too much. It was not a scary prospect – in a way that I think it is now.

KB: But why do you think it was in the air that places like Backspace emerged – and there were so many at the time, whereas actually, if I look around now I don’t see very many places like that at all? Is that only to do with economic circumstances? You were mentioning the lack of urgency that you realized at the time, but dissatisfaction in the arts and culture is probably stronger than ever now. Even in the mainstream you can see much more of a harsh critique of the art circuit than you would probably have found in the 90s.

JBS: I would say it is both economic and cultural. I think rent levels are clearly a huge part of this. We are living in the midst of the worst kind of property price spike in history in London. The property values around here have gone up around 30 per cent since the 2008 financial crisis. If you think about Backspace, the mere availability of cheap, former industrial space made it so much more possible. I know it is a very familiar story, but that made a big, big difference. I think the whole way in which the welfare state was still underwriting culture, even if unintentionally, through a combination of benefits, as well as the fact that people received free higher education, free degrees and so on, made an important difference too. You left higher education with no debt or with small debts. People did often have debts, but it was not enough to make them have to conform in a mainstream job immediately. That was the economic side.

FS: Maybe before we fast-forward I would like to add Konrad’s sense of why this was also an urgent project outside Berlin and London. The Viennese situation was not exactly the same as in other places. Why was it that building an independent institution interested you? What was the basic thinking in your case?

KB: I was always interested in that on a personal level, which meant that in a way this was a totally natural thing to do. It always seemed a plausible proposition to me that you have to do things yourself if nobody else is doing them. Austria was historically self-centred and isolated, and the established institutions were not very open to the fields of discourse that my peers and I were interested in, or, maybe more to the point, they were excluded to a large extent. Self-organizing cultural networks that remained largely invisible to the mainstream had been an important source of interesting music or zines for quite a while already. It seemed like a window of opportunity. It was not only necessary but, in a context of new communication technologies, also became possible to empower independent structures. At the time there was no way for artists, activists and independent cultural producers in Austria to use the Net in a meaningful way. Public Netbase was not only the first non-profit Internet provider but also an interdisciplinary platform for sharing skills and discourse.

However the economic aspects that were just mentioned also played a role. One point was that people with skills in this field were able to do a job – let’s say as a web designer – and could work on that for some time and be free for the rest of the month to do projects that really interested them. Not all the spaces in Europe face 30 per cent rent rises and still we see that this spirit has dried up and I wonder if it is just due to economic circumstances. That is certainly a very important aspect; the welfare state has already been mentioned, but Pauline was addressing the interdisciplinarity aspect of this whole topic, the way that people at that time were actually coming together from different sectors of society that are much more apart right now. There were artists and activists, experts and theorists going to the same events and working on the same platform and projects – that was a window of opportunity in a different sense. I wonder why that has gone away. I do not see that happen so much anymore. Basically these fields do not talk very much with each other any longer and I wonder if economics is really the whole story, if this phenomenon can be broken down to just the economic milieu.

FS: No, I don’t think so. I remember for me there was a clear sense that there were no spaces where you could have these kinds of discussions. I had just finished my MA in the early 90s. It was clear in the academic spaces, apart from in computer science, that there was no recognition, no knowledge that something was going on. The same was true to a large degree in many art institutions; there were clearly no established venues to do anything in that field. There was however – as you mentioned – still the possibility of piggybacking on established festivals. There was a sense that people were saying “Yes, something might be going on, but we don’t know what it is, so we have to bring in some people”. That was a very good opportunity to say “Yes, give us money and we are going to do something that you don’t know how to do”. That also afforded a sort of necessity to do something because there simply were not any venues that you could go to unless you created them yourself, along with a sense that at least some institutions were funding projects they did not understand, simply because they believed that maybe they should let other people try it out and get their hands dirty in order to see whether there was really something significant going on.

JBS: I would add that, as we know from the 60s and the 70s, a lot of these experiments had already been tried within the arts; people had both self-instituted and mixed disciplines, as well as connecting culture to political activism, or linking the home to the official space of culture. Somehow in the 80s that process of self-institution, if we can call it that, had seemed to run aground. Obviously the advent of the Internet seemed to promise a kind of realization of these attempts on a higher level. I suppose it was partly the idea that these much more local and community-based projects of the 60s and 70s, which had petered out and been taken over by the state (look at community arts, for example), could be reinvigorated. I think that’s the story: what was seen as a way of resisting state forms of culture became a kind of adjunct to the state’s coordination of cultural and political activities. There was a moment where it seemed this could be wrested back. However, another aspect that was also very important was the euphoria, which we talked about at the beginning, linked to the breakup of the Soviet Union and a true globality of culture, which people were calling “art glasnost” for example. You know, the Net art that inspired me was all about trying to figure out what it meant to be in an art movement that was both global and local. We did not really know what global meant because we didn’t have this image of the globe until the very late 1980s and early 1990s. We were trying to figure that out, but we were also trying to work out how potential for global communication related to specific communities and locales. I think that that was a huge boost in terms of the urgency you were asking about: that was a big part of the urgency, seeing how we could try that experiment of self-instituting of the 60s and 70s again on a higher level, on a much higher plane. It seemed to be panning out well in the anti-globalization movement until it ran aground with 11 September 2001. I think that really marked the end of a first phase, if not the dotcom crash…

FS: One of the points that strike me when I think about all these institutions popping up: there was a clear sense of different ways, again a certain urgency of working together differently and working more as a kind of fluid network rather than as individualized producers.

PMB: When Josie was talking about this second or higher level, I was wondering about who was involved and, very literally, about the technology element. In terms of dissatisfaction with art, for me the attraction of doing a magazine – as one particular media form – was that it was a more collective matter and it got away from that insane premise or imperative to individualize. That is not new of course; these issues also relate back to much earlier periods. However, there was also a dependence on each other for specific types of skills, which I think was really interesting and fun. I think because it was a necessity, you got these interesting new alliances and friendships. I don’t know whether to call it respect, but it was a sort of thinking collectively to make certain projects. The cultures that came with those different skills were seemingly very incompatible, like hacker culture or art culture, but actually turned out to be very compatible.

That was also part of the energy of that time: these quite tribal communities coming together. Not to put too positive a spin on it, and maybe it was very short lived, but in terms of the particular things that got done and also maybe the art that got made, I think that was important. Also, the media were in quite an early stage of development. I could code the website of an organization. I could do our own website. I think, in terms of the splintering back into disciplines that Konrad was talking about, much in the same way, within the domain of art, we have gone back to a landscape of genres of sorts – or at least that’s what it seems like to me within digital art; there is this whole array of types of new media art, rather than a kind of scrum of malcontents coming together. It is related to this maturing of technologies, to software catering for very particular activities and markets, and to the way in which that takes away the need to have those experimental collaborations. I am sure it still happens, but it is not overly accessible to the likes of me with a very, very low level of technical knowledge. That is quite interesting about that moment.

KB: Do you think that this kind of idea of collective work was very much founded in this sort of skills exchange? As you were saying, all these trajectories are older, dating maybe from the 1960s or even much older; and I guess some started at the turn of the last century. After all, we might want to frame the exchange of skills on a much broader level.

FS: I think that is true actually; I wouldn’t underestimate that. Of course, the idea of collaborating and so on is much older, but this gave it a very tangible necessity and also very tangible benefits related to overcoming certain hurdles and trying to find some sort of institutional platforms that would allow scope to do that in something that is both, in a sense – ideological, but also practical. That combination, I think, was part of some of the energy, and if we think about what changed, maybe after 2000 or so, you already mentioned the dotcom crash and September 11th as major changes in the overall social atmosphere and social policies. However, I am also thinking about the emergence of something like social media that suddenly made all these technologies work. Producing them became super-specialized and… if I look at my students, right now they expect something technologically new to come from Google. And they expect things to work out of the box. There is very little patience with things that do not work.

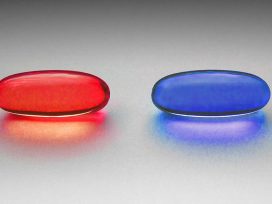

JBS: I had to talk about post-Internet art at an ICA event and they brought me in as the kind of old fogey who can remember the days back before they were born, when web 1.0 was born. By way of an illustration of the difference between the two moments, I compared two self-portraits. One was by Heath Bunting from 2004, and was called Artist’s Self-Portrait Aged 42. His portrait was basically a diagram of all forms of identification and data that comprise subjects; he has made a series of diagrams of different people at different ages, encompassing every single piece of identification and every moment they can recall in their entire lives where they have appeared in a database. After that I showed a grab from Jennifer Chan’s piece factum/mirage, which was a film of an exchange on chat roulette. It was basically an exchange with a perfect stranger, where identity is in a sense construed as very Baudrillardian. It is interesting that we seem to be returning to that welter of images and communication without a referent. The Heath Bunting portrait says a lot about this moment that we were talking about in the 1990s, that sense of DIY, where to construct is also to understand and to know.

That presumption of knowledge is just pointless now; even if it were admirable, it feels like it would be impossible. That is not actually true, but that is the perception, if you like, of the impenetrable complexity of technological, social and global dimensions. I think it is really, really interesting though that now post-Internet artists are making forms of association and alliance; they are doing these surf clubs and making their own spaces to some degree within social media. However I think their point of engagement within this is one of total subsumption, as they like to say. There is this idea that there is no outside space or autonomous culture, and that criticality is a waste of time. These aspects have all been assimilated into the popular form of Web 2.0 or whatever you want to call it, and they are interested in how to work from within that position of subsumption. I think to a large extent it is not working. [laughs] It is a great proposition, but I think in a way they do not realize how they are replaying postmodernism. And that is weird.

We have left modernism and its promises of criticality. These experiments also overlapped with capitalism’s use of culture to make capitalism more persuasive rather than overtly exploitative. However, today’s generation have seen numerous failed attempts to find an outside or position of critique, which implies distance between the avant-garde and the mainstream. I think therefore it is very persuasive to say: how do we work from a position of immanence to capital? It is wrong to say modernism did not understand its immanence, as of course it did grasp this to some degree, but modernism also believed that it could actually break with that immanence entirely or create a true rupture. I think already by the 80s you have people like Hal Foster asking: Can culture be a site of contestation any longer? Because even then he recognized, as did many others, that in post-modernism the critical forms of culture could be digested by capital because it just created a more refined, refractory form of culture for capital, and for the culture industry. Consequently, today artists are saying: Look, we realize, more people listen to pop than Schönberg, for example. [laughs] That is probably not a very good contrast, but they emphasise that people would rather listen to Katy Perry and get a kick from these saccharine forms of pop that we hear now; they want to find within that a kind of affective channel that could be used to blow itself apart. That is the ultimate intention, I reckon, but I don’t think it works.

KB: You describe the so-called “new spirit of capitalism” where any form of resistance is futile. That is an idea you hear a lot in the debate. However, I was wondering: is this affirmative stance something where you still see a kind of subversive background, of affirmation as a tool in the sense of not being openly critical but actually having an influence through over-affirmation. Is it that or is it simply capitulation, where you try to get as good as possible a lifestyle in the creative industry?

PMB: I am not as familiar with these groups. Maybe from a distance I would say: it does seem like over-affirmation, but as such it also seems too conscious to be just about an improvement of lifestyle. There is definitely a preoccupation with form and style in a pointed way, but I suppose that because it is not really my “habitus” I don’t feel I could speak so securely about it, even if I’m dimly aware that it is going on.

JBS: Yes, I guess I have had discussions with people around Arcadia Missa, which is a kind of post-Internet gallery in South London, in Peckham. I have found it interesting to talk to the artists around that, such Harry Sanderson and Rozsa Farkas. I found that their propositions are quite provocative and even persuasive, but when it comes to the art that’s being shown there – not in all cases, but in many – it seems to me that there is a lack of the type of anatomization that you see in the example I gave you earlier of Heath Bunting’s self-portrait, which I think web culture was all about in the first wave. It was about looking at domain name systems, the name allocation system, all of these non-governmental organizations and structures that comprised the web. The culture was trying to understand that. If you think about a piece of work by Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, even the use of the location bar was used to demonstrate that although in a way you are just clicking from one page to another, actually you are going from a server in, for example, Ljubljana, to one in Russia and next to a server in America. It shows you, at every stage, how the fiction is created or what actually underpins the flow of experience and media. This did no t exactly create emancipation, but I think it created a degree of sceptical engagement. However you cannot call this generation un-sceptical; I think they are sceptical, and even quite cynical.

FS: If I look at this now, my students, even those who are engaged in actual, difficult political projects – such as providing education for undocumented refugees and so on – do not care about the big picture. They are very focused in what they do; they do it under relatively difficult circumstances with a clear political idea, but they are not critical in any we-want-to-fight-the-system kind of way. Okay, we have to get this class running, okay, we have to find a new room, okay; we have to… one thing after the other. And we have to create our own platform; it’s all very practical, even though it is an engagement. It is not stupid; it is not just happy hipster surfing around. Again, it maybe has to do with the general shift in property values, with what was once easy-to-get work and is now completely automated: who needs web designers anymore? Hardly anyone… It is all templates now. Stuff like that. There have really been quite substantial changes in the social context.

PMB: However, also technically, to begin those kinds of engagement with any sort of real hope that you could make a change is nearly futile. The fight that you are engaging with is just so… it’s nearly a non-starter. When we did the OpenMute platform around 2003, it was pre-Myspace and pre-Facebook. Looking back after a while I thought: What did we think? Were we completely insane, thinking that we could make a sustainable infrastructure for hundreds or thousands of people, which could do all these things, with only a small group of people? There was such a level of naivety in terms of the temporal and technical resources it takes to create any kind of alternative platform. However, when you have gone through a process like that, you sort of never do it again. I remember there were some people who worked on this tool for quite a long time – I do not remember what is was called, perhaps something like Diaspora; it was like Facebook without the surveillance or something. Do you remember? It was an attempt to make Open Source and genuinely secure social networking. I remember reading about it for a period of at least three to five years.

However, if you are thinking of the actual difference in capital investment needed to make something like that happen with voluntary energy, probably mostly working with small bits of investments from do-gooders etc., compared to what’s been chucked into this other, dominant environment (of Facebook), then it is just a joke. I think what you said about the students is very familiar from debates that we have witnessed here: for example, do you use Facebook for political activity or not? Of course everybody knows you should not, but at a certain point it just becomes regarded as the environment within which you practically need to operate. One thing that is quite fascinating is the amount of time it sucks out of people’s lives through some sort of mixture of distraction and genuine information exchange. That is something I wonder about. We talked about property and values and the economic environment, and Konrad more or less rejected the idea that these could be the only considerations. I think there is something else ineffable, and admittedly, there are the life conditions where – as Josie said – culture was underwritten through these other unseen, uncounted resources and benefits, etc. Yet it is very palpable now that it is so much about time. People are weighing up: shall I do this? Shall I do that? There is not a lot of that uncounted energy or time left to deliberately experiment.

JBS: I think on a sort of cosmic level that the amount of energy that has been taken out of the ground in order to accelerate the flow of communication and information is historically unprecedented and overwhelming. For example I heard one statistic: apparently, more photographs have been taken in the last year or two than in the entire history of photography. Just think about what that is actually doing, the impact of this extreme fuelling of information and communication… I am with Franco Berardi Bifo on this point; I think it is just organically un-digestible, for we cannot metabolize that ferocity of information circulation. That is not all: obviously it is, as we know, assimilated by capitalism in order to find a way to make every part of life productive. Something that was a kind of seemingly utopian medium becomes the very mechanism of deeper enslavement. That creates a kind of revulsion to the medium. On some level it is irresistible and we must play with it and we must use it and we must integrate it into our lives. Yet it is also part of the cage and it feels like that: who would want to propose alternative platforms of communication – that is just more communication! I am taking an extreme position, but it just does not have the appeal that it had 20 years ago.

PMB: Another really fascinating thing that I am hearing from a lot of different corners: whether you call it overproduction or hyper-production, it is a sense that because everybody is producing, the whole model of cultural consumption, reading and discourse is being turned on its head. At the same time, magazines are finding it hard to find the contributions to put on their pages. This is something that Colin Robinson at publisher O/R Books is very interested in: the idea that there are more bookmakers than book readers. There is a sort of symmetry coming to pass, which is quite unseen and is gradually creating a model that is really different to the model we actually acknowledge as cultural producers trying to do something consciously critical. I think the time element sits in that equation too. I was talking to somebody from Radical Philosophy recently, and he also said that one of their biggest practical problems is getting enough articles in the magazine. That too may be to do with these difficult life conditions and lack of time.

FS: But how does that square? I found myself agreeing with both statements that you made. They do not really add up. On the one hand, you say that there are more writers than readers, in this metaphorical sense, and on the other hand there is not enough writing to fill up the magazine.

PMB: I think it has something to do with a dispersion of that content in lots of different places, maybe smaller places. Maybe there is some sort of self-institution going on, and then maybe a fracturing of these forms we are familiar with, e.g. the long-form essay, into a kind of hyper-production across lots and lots of different spaces. We all know individuals like this and the amount of production they are capable of, yet how hard it is to get them to write one article. It is also that. I remember Ted Byfield and McKenzie Wark doing an event in New York. It was a very small discussion round, and I took part in it to talk about the early history of Mute. We were talking about email-lists as a kind of precursor to social media and what the differences were. I think those differences are pretty fundamental. Maybe I am wrong, but the sense of gathering differs – even though you can in a sense achieve the same, maybe, on a thread on Facebook as in an email-list forum, and you do not want to be too hard and fast about the differences; it is interesting.

FS: I think the differences are really substantial. Maybe you can assimilate one in the other. What strikes me as really hard to even get people to understand now is that on an email list, for example, the others are not your “friends”, but rather it is simply a group of people, and it is always the same group of people. Certain discussions can certainly also take place in threaded kinds of fora or on Facebook, but there the people involved always change. There is this sense that you develop over time: yes, there are any number of people – a dozen, a few hundred, maybe a thousand, maybe a few thousand – in the same space over a longer period of time. This is very hard to assimilate now. I would not make it a big conspiracy, but I don’t think this is a coincidence. It somehow gels with this individualistic consumer model.

KB: Before you have to go, I wanted to come back to that scenario of more writers than readers. You were mentioning this kind of cosmic attention-harvesting, an industrial cognitive farming, and on the other hand, a set-up in which everybody has to be creative now to even get a job as a dishwasher. Were you saying earlier that any attempt to bring about change or make a difference is a non-starter? Are you implying that everything is so overwhelming today and nobody is naive enough anymore to propose anything like change?

PMB: Oh no. That is to do with a particular kind of philosophy that believes that you need to read politics into tools, to the degree that this should be your point of focus in terms of political change. I am not saying there can be no change, or that you cannot do anything. What I am saying is that really responding to the threat of a phenomenon like Facebook, or to the real meaning of it in our lives, and developing a genuine technical alternative is such a hard project that I think it is understandable that people do not do it. It is understandable that people say: okay, I’m willing to organize my political work on Facebook instead. What I am not saying is that political change is impossible or should not be attempted. There are lots of ways in which that is being illustrated right now, instances of people organizing and working for political change. A very embodied or materialized understanding of technology, and the point we were talking about earlier where people had a vision of cultural activity focused on that line between media and politics, have become so centralized that I think it is very hard to answer the challenge through tools, through media projects. Of course it is hard to answer the challenge of politics, but in that area I am much more hopeful that change is possible than I am about the kind of alternative Facebook. I think they are two slightly different things.

JBS: But then that is not separate – the power embodied in technology or the way capitalism drives forward certain tools of production that create new realities. I guess we have not really talked here about algorithmic types of generation. I am thinking for example about how you deal with high-frequency trading. Maybe it’s just that you have to focus on the social end of the spectrum rather than concentrating on the technical end of the spectrum as we tried to do in the 1990s. I am really not certain, but it just seems to lead to more complexity that is disempowering. However I find it hard to find a concluding point quite honestly, but then, who wouldn’t?

FS: We wouldn’t be here if we had concluding points. So where does it leave us now? Or where does it leave Mute now? Are you going to close the magazine?

PMB: No!

FS: Okay, why not?

JBS: Because we are mad. Officially. Because we love each other.

This article was produced in cooperation with the World Information Institute.