“This is an earthquake”: The far-right rises as EU elections signal a massive shift across Europe

Associated Press, 26 May 2014

That “earthquake” in Europe? It’s far-right gains in Parliament elections.

CNN, 26 May 2014

The media headlines directly after the 2014 European elections had been written months before. The only real question was what the hyperbole of choice was going to be. In the end, “earthquake” won. European elections have long been associated with the rise of far right parties, but 2014 was nevertheless special. For more than a year, European elites had warned of a huge electoral victory of “Europe’s populist insurgents” (Economist), which the media loyally declared on the night of 25 May 2014, not even awaiting the full results. Pointing to the remarkable results in a few specific countries, “the” far Right was declared the main winner of the 2014 European elections. This gave way to apocalyptic prophecies of the alleged dawn of a new eurosceptic era.

This essay analyses five aspects of the far Right in the 2014 European elections. First, it gives a short overview of the pre-election period, discussing the far Right campaign as well as the anti-far Right media campaigns. Second, it presents the electoral results of far right parties and compares them to the 2009 European elections. Third, it analyzes the 2014 results in more detail, showing that the far Right hardly broke new ground, and mainly succeeded in countries where it was already well established. Fourth, it examines the presence of the far Right in the new European Parliament, highlighting the continuing failure of political group formation. I conclude with a short assessment of the main consequences of the far Right’s “success” in the European debate.

The pre-election period

The far Right dominated the international media coverage in the run up to the European elections. Years before the elections were actually held, commentators were already speculating about a rise in support for the far Right. For example, Newsweek proclaimed “The rise of the extreme Right” in September 2010, with most international media publishing similar stories in the next years. In 2012 the media were put into a real frenzy by the strong performance of (new) FN leader Marine Le Pen in the French presidential elections and the surprising success of the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn (or “XA” as it is known in Greece) in the Greek parliamentary elections. On top of that, the US government shutdown in 2013 led to warnings of a possible EU shutdown, as a consequence of the imminent success of “Europe’s Tea Parties” (Economist) in the 2014 European elections.

The far Right added to these expectations with the new, and quite unexpected, electoral and political alliance between Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders, leader (and only member) of the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV). Wilders had always kept his distance from the FN, arguing that the party was far right and anti-Semitic, but had changed his position in light of the new FN leadership (his official reason) and his own party’s electoral defeat and political marginalization in the Netherlands (the more probable real reason). In November 2013, Le Pen and Wilders announced that they would constitute a political group in the European Parliament, the European Alliance for Freedom (EAF).

While euroscepticism was still the default far right position during the 2014 European elections, as it has been since at least the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, almost all parties had become more critical of the European Union as a consequence of the economic crisis in general, and the bailouts in particular. For the first time, several of the most successful parties were arguing for their country to leave the EU (e.g. FN and PVV). The other EAF members continued to call for reform rather than the outright rejection of the EU, even though the implied reforms amounted to the rejection of the EU’s core foundations.

The elections

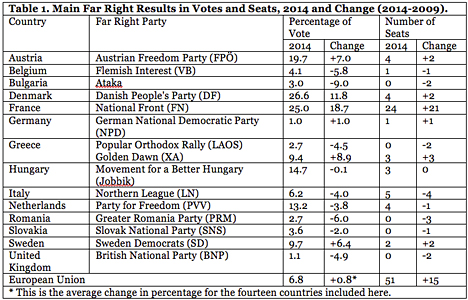

As the media never tired of noting, far right parties increased their representation in the European Parliament (EP), gaining a record 51 MEPs, up by 15 since 2009 (see Table 1). The precise numbers depend on issues of conceptualization and categorization. Using a broad interpretation, the British anti-racist organization Hope Not Hate calculated that 16,835,421 Europeans (or 10.3%) voted for a far right party in the 2014 European elections. This was over six million voters more than in 2009, or roughly 160% of the 2009 far right electorate. Following my more narrow interpretation, 11,095,265 people (or 6.8%) voted for far right parties. This notwithstanding, it is clear that Europe as a whole wasn’t hit by a far right earthquake.

As has been the case since the emergence of the so-called “third wave” of far right parties in the early 1980s, the successes of individual parties differed significantly across the continent. For example, only ten of the twenty-eight member states (i.e. 36%) elected far right MEPs. Moreover, far right parties gained (additional) seats in just six countries, while they lost seats in seven others. Most striking of all, while two far right parties entered the European Parliament for the first time (SD and XA), five lost their representation altogether – Attack in Bulgaria, the BNP in the UK, LAOS in Greece, PRM in Romania and SNS in Slovakia.

In fact, in many ways the success of the European far Right is largely the success of the FN. Its 4,711,339 voters account for 42.5% of all far right voters in the 2014 European elections! Similarly, the increase in FN support, of 3,619,648 voters, constitutes roughly two-third of the new far right electorate. Not surprising then that the total increase of 15 far right MEPs, compared to the 2009 election, was almost exclusively because of the huge gains of the FN, which won an additional 21 seats, compensating for the various losses in other countries. The FN now holds almost half (41%) of all far right seats in the European Parliament.

Analysing the 2014 far right results

One of the main problems with political analyses, both in academia and the media, is that they are obsessed with the alleged “new”, at the expense of the often much more relevant “old”. This holds particularly true for analyses of the far Right, which has been proclaimed to be “new” several times since the emergence of the original “new extreme Right” in the early 1980s. So, what is new about the 2014 European elections?

First and foremost, for the first time in postwar history, far right parties have come first in nationwide elections in an EU member state. As expected, the FN topped the polls with 25% of the vote, well ahead of the mainstream rightwing Union for a Popular Republic (UMP), with 20.8%, and the mainstream leftwing Socialist Party (PS), with a mere 14%. More surprising was the stunning victory of the DF, which gained 26.6% of the Danish vote, leaving the mainstream left Social Democrats (S) and mainstream right Danish Liberal Party Venstre (V) well behind, with 19.1% and 16.75 respectively.

Both of these cases are well-explained by the “second-order theory” of European elections, which argues that big parties loose, particularly those in government, and turnout is low. This is particularly the case when second-order elections come midway through the first-term election cycle, i.e. in between two national parliamentary elections, as was the case in Denmark and France. This notwithstanding, the DF won 165,231 votes more than in the 2011 parliamentary elections, while the FN attracted 1,182,966 more voters than in the 2012 parliamentary elections (though 1,710,087 less than in the 2012 presidential elections).

Interestingly, the two parties that registered the highest far right scores in recent parliamentary elections, the FPÖ and Jobbik, did not do that well in the European elections. After having gone head-to-head with the two big parties, the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SPÖ), the FPÖ finished well behind them. Its 19.7% was 7% higher than its 2009 result, but 0.8% lower than the 2013 parliamentary election results. Even more striking was the result of Jobbik, whose 14.7% was 0.1% lower than the 2009 score and a decisive 5.8% lower than in the 2014 parliamentary elections the preceding month. These results are also in line with second-order election theory, which argues that European elections held shortly after national parliamentary elections are “throw-away elections”, which benefit governing parties still enjoying a honeymoon period and hurt protest parties, because people vote with the heart rather than the boot.

The second new feature is the election of representatives of neo-Nazi parties – the NPD (Germany) and Golden Dawn. Extreme right parties have been represented in the European Parliament before, i.e. the Italian Social Movement (MSI) and its various radical splits, but not in its racist neo-Nazi variety. While the NPD only entered the European Parliament because of a change of the electoral rules, Golden Dawn gained a staggering 9.4% of the vote, despite the fact that the party is under investigation for being a criminal organization and its main leaders were imprisoned during the election campaign.

In contrast to these two new developments, the European elections mostly showed more of the same, both empirically and theoretically. I will focus particularly on three specific features: (1) the role of the economy; (2) the East-West divide; and (3) the importance of “rebranding”. All of these factors have been regularly mentioned by academic and non-academic commentators in media reports on the 2014 European elections, and have been addressed in academic research on the far Right since the 1990s.

The idea that far right parties profit from an economic crisis has been around since Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Weimar Germany in the early-1930s. This notwithstanding, the thesis does not hold up under empirical scrutiny. This is true for both the Great Depression and the Great Recession, and was confirmed in the 2014 European elections. Most striking, only one of the “bailed out” countries returned far right MEPs (Greece) – interestingly, in four of the five bailout countries, it was the far Left that made (significant) gains. In fact, with the exception of Hungary, far right parties gained their best electoral results almost exclusively in countries that were only little or moderately affected by the crisis, at least compared to other EU countries: Austria, Denmark, France, Netherlands and Sweden.

These results are fairly consistent with the rise of far right parties since the mid-1980s, at least in western Europe. Not only did the parties emerge in a period of relative affluence, but they tend to perform best in the richer countries (e.g. Denmark, Switzerland) and regions (e.g. Flanders, Northern Italy) in western Europe. The explanation is that contemporary far right parties, just like Green parties, are mainly a post-materialist phenomenon, conducting identity politics and emphasizing socio-cultural issues. Economic issues are secondary for both the parties and their voters. Hence, in times of economic crisis, when socio-economic issues push socio-cultural issues to the sidelines, far right parties have little to offer and (some of) their voters will either not vote or look for a party with a more pronounced economic profile (and competence).

A much less noted development is the East-West divide in far right electoral success. Again, with the exception of Hungary, the far Right lost its entire representation in Central and Eastern Europe. Supposedly, eastern Europe provides a fertile breeding ground for far right parties, including broadly shared prejudices towards minorities, high levels of corruption and a large reservoir of the so-called “losers of the transition”. One explanation for the abysmal performance of far right parties in eastern Europe is that mainstream (rightwing) parties in the region leave little space for the far Right, given their authoritarian, nativist and populist discourse. This is often mentioned as an explanation for the quick demise of the far right League of Polish Families (LPR), as a consequence of the rightwing turn of the conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party. However, in Hungary the at least equally authoritarian and nationalist Fidesz is confronted with the only strong far right party in the region, Jobbik. In this context, commentators argue that the relationship is actually the reverse, in that a very rightwing mainstream party legitimizes the far right, which helps them gain support.

Within the west European context I have called this the “Chirac-Thatcher debate” and suggested that both arguments can be true. The missing piece in the puzzle is an intervening variable: issue ownership. If a far right party is able to “own” far right issues like crime, corruption and “ethnic minorities”, it will profit from the rise in salience of that issue as a consequence of the discourse of the mainstream (right-wing) party. If it does not, the mainstream (right-wing) party can occupy the unclaimed issue and own it, leaving little space for the far Right. What sets eastern Europe apart from western Europe is the lack of institutionalized parties and a stable party system, which also means that few parties, mainstream or far right, can establish let alone hold onto issue ownership.

Finally, a lot of commentators have explained the success of the far Right in general, and the FN in particular, by arguing that they have rebranded, making their ideologies more moderate and their parties more professional. It is this alleged “far right 2.0” that succeeded where the (presumably) “far right 1.0” of anti-Semitic leaders and racist skinhead supporters failed. The thesis of a “new radical right” is actually quite old and has been used several times since the early 1980s. Whereas Marine’s father Jean-Marie Le Pen has become a caricature of himself in recent years, twenty-five years ago he was considered one of the most charismatic political leaders in Europe. Similarly, current FPÖ-leader Heinz-Christian Strache, or “HC” as the party’s cult of personality would have it, is heralded as part of “a new generation of leaders” that look much more respectable than the “historic leaders” of the 1980s and 1990s. But journalists wrote exactly the same about his predecessor, Jörg Haider, for whom the term “designer Fascist” was invented.

The far Right in the European Parliament

National parliamentary elections are important for the constitution of both the parliament and the government. This is not the case in the EU, where the European Commission, and to a certain extent the European Council, constitute the “government”. The post-election period in the European Parliament is instead dominated by the formation of political groups. To be officially recognized, a political group requires 25 members from at least one quarter of the members states (seven in the current legislature). Most committee positions, funding and speaking time is divided on the basis of political groups, which leaves the non-affiliated MEPs, the so-called Non-Inscrits (NI), quite isolated and powerless.

At first sight, the far Right should not have experienced any problems in forming a political group. It has 51 seats from ten member states. However, political group formation is determined by both ideological and strategic considerations. Simply speaking, ideologically there is a divide between extreme right and radical right parties, while strategically there is a division between nationally accepted and ostracized parties. This, together with conflicting nationalisms and personalities, makes far right collaboration in Europe problematic, as can be seen from their poor track record.

In the previous legislature, far right parties were divided between the Europe for Freedom and Democracy (EFD) political group and the NI. After frantic negotiations within the broader right-wing eurosceptic camp, involving the “soft eurosceptic” European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) as well as the “hard eurosceptic” EAF and EFD, the far Right has become even more dispersed. First of all, the EFD lost its old far right members – the DF joined the ECR, the LN the EAF, and the SNS lost its representation – but gained a new one, the SD. Second, the FN, FPÖ, PVV and VB have so far been unable to constitute the EAF, and remain temporarily in the NI. Finally, the more extreme far right parties (Jobbik, NPD, XA) are considered beyond the pale for all three groups and will probably stay in the NI for the duration of this legislative term.

Conclusion

The 2014 European elections were not a “political earthquake” as a consequence of massive far right gains, as the international media so eagerly publicized. At best, they brought some local shocks, mostly caused by well-established far right parties that have been operating in a “new” style for decades. Similarly, the much-hyped European Alliance for Freedom (EAF) confirmed the historical pattern of European collaboration between far right parties: fragmented and largely restricted to the usual suspects. Consequently, despite the media hype, the European elections have hardly changed the position of the far Right within European politics.

Far right parties remain marginalized within the EU power structure, lacking individual representation in the European Council and European Commission, and group representation in the European Parliament. In fact, within the European Parliament, the Europhile political groups continue to control all chairperson positions of the powerful parliamentary committees, excluding all eurosceptic groups. Moreover, the far Right lost influence in the only hard eurosceptic group, as Europe for Freedom (EFD) transformed into Europe for Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD), replacing several far right parties with the idiosyncratic Italian populist Five Star Movement (M5S) of Beppe Grillo.

Perhaps there has been a small effect on the political discourse, as the alleged rise of the far Right has further helped to mainstream soft euroscepticism. When the Dutch conservative-liberal Premier Mark Rutte remarks that “the EU has to go back to its core”, and the German Social Democratic Party leader Sigmar Gabriel states that “Europe is an elite project, too remote from the citizens”, soft euroscepticism has truly arrived in the European political mainstream. Obviously, the transformation of the EU itself, as well as other factors like the economic crisis and the bailouts, play a much more important role in the mainstreaming of soft euroscepticism than the alleged rise of the far Right. But the electoral pressure from hard eurosceptic parties, most notably of the far Right, has given mainstream leaders both cover and incentives to adopt soft eurosceptic rhetoric (rather than policies).

But the alleged rise of the far Right has also helped discredit hard eurosceptic arguments, ranging from a fundamental reform of the EU to national exit options. Rather than having to engage in a fundamental debate on these arguments, europhile and soft eurosceptic politicians can reject these arguments by linking them to the far Right. For the best result, a reference to Golden Dawn will end any debate. While the far right straw man is certainly not new to the European debate, it has become increasingly important in a soft eurosceptic world. Whereas before any critique of the EU could be disqualified as eurosceptic, which was generally perceived to be bad and outside of the political mainstream, the boundaries are much less clear now. But one thing remains clear to all: if there is a link to neo-Nazis like Golden Dawn, it is bad!

Routledge Handbook on Euroscepticism