Why don’t we do it in the road? No one will be watching us

Why don’t we do it in the road?

‘Let‘s be happy, let‘s be monsters’

For me, the 1968 Beatles track cited above instantly conjures up an uplifting, joyfully provocative sense of mutiny. I was seventeen during the tumultuous events of that year and the excitement of rebellion was bound up with the thought that one could get one over on the repressiveness of bourgeois society by living out a liberated sexuality. It wasn’t by any means all about getting away with forbidden pleasure, but rather about the ‘whole’ and ‘making love not war’. In other words, it was about freeing society from its penchant for aggression, which, if you believed Wilhelm Reich, resulted from the suppression of a fulfilling sexuality.

Fifty years on, in Spring 2018, the Italian luxury brand Gucci presented their latest fashion collection under a slogan borrowed from the May 1968 Paris protests. It read: ‘Liberté, Égalité, Sexualité’. Taking up the buoyant image of the power of a liberated sexuality to induce social change, expensively-produced photo-galleries and video clips showed models posing against the backdrop of that momentous year’s demonstrations and revolutions. The images were accompanied by a song with lyrics that expressed a more contemporary spirit: ‘It’s you and me and the future. We don’t need anything else.’

Out of its historical context, the 1968 Beatles song has also provided the soundtrack to a series of rather less edifying images. In May 2018, a selection of pictures appeared online, recording the start of the season in Magaluf, the party capital of Mallorca. The images depicted young people from Britain and Germany, both girls and boys, apparently united in their desire to transgress and ‘doin’ it in the road’. Evidently, the idea wasn’t to resist any latent aggressive impulses but, on the contrary, to live them out through regressive hardcore sex. The images reveal the hands-on expression of an unmistakable blend of both sexual and violent urges. They give no indication that such a mix might pose a problem (at least not in peacetime), even when this vision of intimate union between the genders is tarnished by reports of rape – unless you assume that violent sex is what the women depicted in these scenes are looking for. It bears pointing out that the roles in this ‘Happy Monster’ scenario are very unevenly distributed: while the male monster is stylised as a hero, the female is a whore – and for her, it’s a matter of ‘Rape, Phil? … How can you rape a whore?’

Judith and Holofernes (oil on canvas, 1612-13) by baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi. A rare female master in the seventeenth century, Gentileschi was long been believed to have taken visual revenge on her tutor for raping her. Image source: Wikimedia.

‘But war is war… ’

Further examination of the 1968 era reveals that a description (no matter how dense) of incidents where sex and violence merge into an eruptive exercise of sexual force doesn’t necessarily tell us what lessons this kind of scrutiny might instil on the relationship between sexuality and violence in war – or, for that matter, in peacetime. During a three-day ‘Winter Soldier Investigation’ event organised early in 1971 by the US organisation Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) in Detroit, Michigan, more than a hundred Vietnam veterans spoke in explicit terms about the sexual violence they had perpetrated in wartime. The reports given by these soldiers, who were overwhelmingly very young, were captured in the film Winter Soldier.

The fact that in these reports, as in other contemporary accounts, what is described as violence of a sexual nature, carried out not in parallel with but during combat operations, was scarcely remarked upon at the time. It hardly featured at all in contemporary debates about the liberatory potential of sexuality. Close attention to the video clips, and the tremulous way in which participants recount the acts of violence they committed, reveals their horror at their own actions rather than any empathy with the suffering of the victims.

In his book Achilles in Vietnam, the American psychologist Jonathan Shay argues that soldiers, traumatized by their actions, became victims of their own crimes. In a passage under the heading ‘Pissing Contests’, he calls for understanding from victims towards the perpetrators, suggesting that they are casualties as well: ‘One would think that severe psychological injury would give rise naturally to shared compassion and mutual respect among the many diverse groups of trauma survivors, such as have lived through genocide, political torture, domestic battering, incest, war, abusive religious cults, and coerced prostitution. Unfortunately, it has not.’

Shay concentrates principally on the psychological consequences of soldiers’ military conditioning. His reflections are not especially fertile ground for seeking a precise definition of the relationship between sexuality and violence. They do not allow the reader to draw conclusions regarding what these soldiers did to whom; neither do they offer insight into underlying assumptions or experiences linked with the soldiers’ actions.

Sequences like the following, from the Winter Soldier documentary, hint at how easily notions of making love and war co-existed in the minds of soldiers, or at least how little they reflected upon the combination: ‘They were supposed to go after a woman they called the Viet Cong whore. They went into the village and instead of capturing her, they raped her – every man raped her. As a matter of fact, one man said to me later that it was the first time he had ever made love to a woman with his boots on. … At any rate, they raped the girl, and then, the last man to make love to her shot her in the head.’

This Kraussian access to a forbidden, though widely recognized, affinity between violent and sexual urges also features in narratives from other theatres of war. It tends to suggest an ambivalent attitude towards the desire and sense of prohibition/compulsion that variously underlie acts committed in different circumstances.

In one section of his book, entitled ‘Suffered Exclusively or Primarily by Women after Defeat’, Jonathan Shay reinterprets US writer and feminist Adrienne Rich’s analysis of the roots underlying the enduring consequence of fateful events: ‘Rape is a part of war; but it may be more accurate to say that the capacity for dehumanizing another which so corrodes male sexuality is carried over from sex into war … The chant of the basic training drill: “This is my rifle, this is my gun [cock]; this is for killing, this is for fun” is not a piece of bizarre brainwashing invented by some infantry sergeant’s fertile imagination. It is a recognition of the fact that when you strike the chord of sexuality in the … [male] psyche, the chord of violence is likely to vibrate in response, and vice versa.’

Shay’s analysis offers room for the hope expressed in the once-popular slogan: ‘Make Love, Not War’. In contrast, however, contemporary feminist analysis has contended that amalgamating sexuality and violence is a component of the patriarchal rule that serves to establish and maintain the balance of power between the genders.

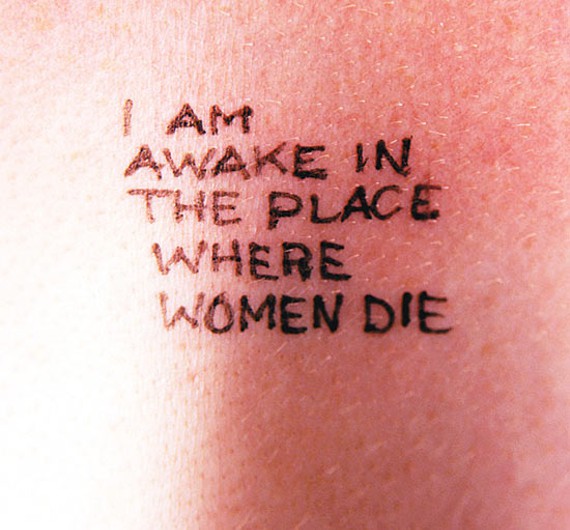

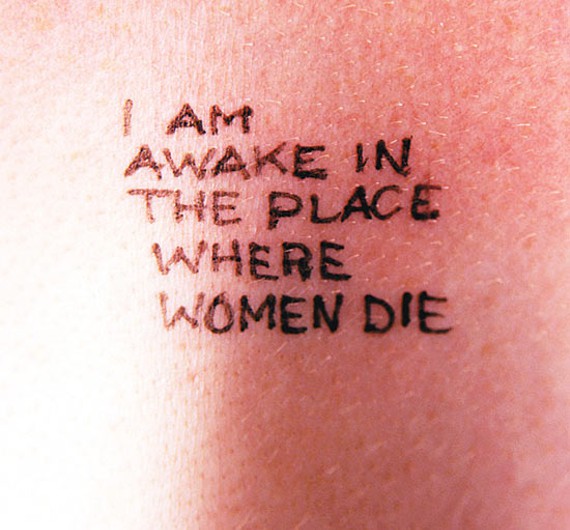

Jenny Holzer – Lustmord, I am awake in the place where women die, 1993-1994, ink on skin Photo via Public Delivery.

‘The Will not to Know’

All attempts to locate sexual violence in a state of exception, to pathologize and reduce it to an instrument of domination in terms of power criticism, or to try and strip it of its authentic sexual content with talk of sexualized violence, act to erase a substantive feature of this form of violence.

Conventionally, we are mindful of the fact that all social restrictions as well as derogations relate to a public consensus according to which the exercise of violence is forbidden and to be punished. The legitimation of brutality – in the case of war, for example – is the prerogative of the state. A person beaten up in the street may not be able to rely on the wholehearted sympathy of onlookers and might have to contend with the accusation that she or he contributed to the attack through some sort of provocation. However, they can assume that their experience of violent bodily harm will be unequivocally seen as a negative experience.

Victims of sexual violence are often denied even this kind of clear-cut recognition. The complication lies in the fact that have been subjected to an attack made against a body that is capable of experiencing lust as much as pain. Sexual violence subjugates the victim’s body with physical pain, and at the same time usurps its libidinal capacity. An attack on the sexually sentient body induces a sense of helplessness twice over – and this is true not just of the victim but of possible observers as well.

On the one hand, due to the suspicion (whether explicit or implicit) of an ambiguous reaction to the attack on her or his part, the victim is often denied both empathy and a clear recognition that the assault has been an injustice. Such preconceptions, which see any friendliness with the perpetrator as suggesting possible consensual relations between attacker and victim, exert a substantial influence over the judiciary to this day. The assumption is often that ‘she asked for it’. But these prejudices do more than throw the victim’s words into doubt. They additionally strip the sexual attack of one very significant aspect: the onslaught on the victim’s bodily and sexual integrity.

Susanna and the Elders (oil on canvas, 1610), by Artemisia Gentileschi. Photo is public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

It seems to me that, rather than invoking this aspect of the assault to exonerate the perpetrator, it may be possible to offer victims of sexual attack a path to justice through an indictment of precisely this act of violence against the victim’s libido. This cannot be achieved, however, if one conceives of the crime of rape as being, in Michel Foucault’s famous phrase, an ordinary act of violence no different from ‘a punch in the face’.

If the aggressor mutilates and kills the victim after the rape, the nature of the attack – though previously in doubt – is seen, cynically, as proven. This is, not least, because the respectively active and attacked sexualities of the perpetrator and victim, which were expressed in the rape, can now be marginalized. In this context, the call to ‘make love, not war’ sounds like a doomed attempt to drive out one evil by invoking another.

Congruences

In public consciousness, the notion that violence and sexuality exist in a dynamic relationship is as prevalent as it is unspoken. A conspiracy of silence and obfuscation, of belittling nods and winks with occasional histrionic expressions of horror, is deployed to delimit and fend off confusion or threats to the normative social fabric, associated with this dynamic.

The relationship between power and sexuality, like the connection between power and domination, is a classic subject matter for theoretical debates. Jan Philipp Reemtsma notes that violence is often implied when power and domination are under discussion. He also argues that while power and domination are a priori positions which permit the exercise of violence, they do not necessarily entail it. Nor do analyses rooted in a theory of power per se shed much light on the relationship between sexuality and violence. At best, they point to violence as a means of creating specific conditions, but say nothing about the meaning of the phenomenon itself.

One exception is psychoanalytical and sexological work which probes the relationship between sexuality and violence, exploring insights into instincts and their vicissitudes, and researching what individual findings can tell us about a subject’s social or cultural environment. Volkmar Sigusch, founder of Critical Sexual Studies, makes the case that sexuality can potentially also be seen as a ‘wellspring and crime scene of unfreedom, inequality and violence’.

Both sexuality and violence can be described as experiential relationships which underlie the vital, affective expressions of gendered bodies. Such affective expressions are structured through bodily experiences and psychically internalized incidents, as well as through constructions of meaning adopted in particular historical, social and cultural contexts. Today this primarily implies a binary and hierarchical gender structure.

With these co-ordinates as a starting point, anatomical, hormonal and physiological preconditions must also be taken into account to permit the meaningful understanding of sexual and violent behaviour and experience. Behavioural and experiential relationships are built up by communicative, reciprocal interaction. (This also applies, incidentally, to auto-erotic or self-destructive acts, which are ultimately manifestations of reactions to social and emotional experiences).

Robert Stoller notesthat both violence and sexuality elicit states of arousal accompanied by positive as well as negative expectations: lust or pain, liberation or trauma, success or failure, safety or danger. As risk and danger are inherent to the state of arousal, anticipatory desire is often accompanied by a feeling of helplessness, which, as Léon Wurmser notes, can manifest itself in sensations of fear and shame.

The burden of lust

The psychoanalytic theory of drives says that the freedom of the subject to give in to a state of lustful arousal, or else avoid the risks and fears it brings through aggressive coping or passive avoidance strategies, is severely limited by the fact that ‘desire, [sexual] drive – as a limit concept between the bodily and the psychological, a psychosomatic unity – thwarts the hopes and wishes of the conscious.’

This understanding of the ‘inaccessibility of bodily desire’ is nonetheless problematic. It can lead us to regard ‘being overwhelmed’ as an affective state for which the active subject cannot be held responsible. This could support the argument that states of arousal elicited by sexual desire or violent urges can be interpreted in wholly biological terms.

Stoller, however, sees in the hostility to some degree underlying sexual excitation, a biographically specific possibility of overcoming the sense of threat inspired by arousal. ‘My theory is as follows: in the absence of special physiological factors (such as a sudden increase in androgen levels affecting either sex), and putting aside the obvious effects of a direct stimulation of erotic body parts, it is hostility – the desire, overt or hidden, to harm another person – that generates and enhances sexual excitement. The absence of hostility leads to sexual indifference and boredom. The hostility of eroticism is an attempt, repeated over and over, to undo childhood traumas and frustrations that threatened the development of one’s masculinity or femininity. The same dynamics, though in different mixes and degrees, are found in almost everyone – those labelled corrupt or nefarious and those not so labelled.’

William Simon and John H. Gagnon counter Stollers’s thesis, with the argument that it invites the reverse conclusion. They write: ‘in many people, sexual arousal is what initially gives rise to hostility. In this context, hostility could be seen as a moralistic masquerade that sexual desire sometimes uses in an attempt to confound the preventative measures of the autonomous inner eye, in order to permit worrisome feelings or constructions of the self to find expression. The hostility the script directs against the other, or that it encourages from the other against the self, cannot be the source of desire, and instead serves merely to legitimise it, making it socially acceptable and plausible.’

The authors take a different approach to accentuating the coping strategy of using hostility to ward off frustrations. But ultimately their argument leads, like Stollers’s, to the implication that the burden should be located, alongside lust, in the ‘steam boiler model’: the helplessness experienced in the face of intense feelings, anatomical urges and drives.

Corresponding potentials

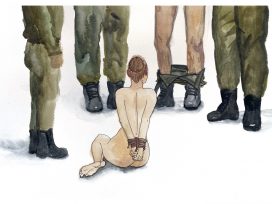

Sexual and violent interactions incorporate interdependent potentials: latent excitement will intensify only if it encounters excitability in some form. During a violent sexual assault, the perpetrator fantasises that he has the ability to arouse the victim against their will, forcing a bodily reaction though physical stimulation. A witness from Burundi, who in 1999 fell victim first to rebels and later to soldiers fighting on behalf of the government (from whom she had expected assistance) reported:

They bound me like Jesus on the cross, with my arms and feet tied to four trees. I shook, I cried, I prayed to God. One man kissed every part of my body and didn’t see me crying or my attempts to voice my anger out loud. He silently penetrated me with his penis, so hard I thought he was using a knife. He ejaculated over my body and I had to throw up. The first man went away, and I hoped I’d be dead in a few minutes. Then a second man did the same to me.

Ilka Quindeau says that the ability to feel lustful desire is predicated on the experience of being desired. If the sense of being desired (defined as a positive experience) is absent, then sexual desire can be experienced as a threat, and as subjugation by an ‘other’ which is then deflected, through an act of sexual violence, against that other. This is clearly illustrated in the report of an Algerian witness who became the victim of a mut’ah or ‘temporary pleasure marriage’ in 1995. ‘They covered my face, and I couldn’t see anything. They told me not to look at them. They shouted at me: “you should be ashamed!” They raped me one after another and yelled evil stuff.’

According to Heinrich Popitz, the power to inflict injury can only be realized in the presence of a counterpart vulnerable to injury. Pursuing Popitz’s thesis, Wolfgang Sofsky writes:

‘Human beings are victims of violence because we are bodies. Given that we possess a body, we are in a position to transform others into victims. This dual physical existence defines our relationship to violence. We make use of our bodies to perform actions, but as bodies we are doomed to suffer. We are both capable of violence, and subject to violence. The body can inflict injury and is open to receiving injury.’

The fragility of this position arises from the fact that the power to inflict injury, and vulnerability to receiving injury, are inherent to an equal degree in every individual. Accordingly, using our power to inflict injury could also be interpreted as an act that represents an attempt to nullify the actor’s vulnerability to receiving injury.

The experience of pain and that of lust are both bound to the body. The encounter that the contemporary image of sexual love promises the highest level of human joy (namely the lustful merging with another human being whose body and spirit are beloved) proves, through inflicted pain, to be a destructive attack on the self: ‘The body is not an element of a human being, but rather constitutes its centre. Physical injury also affects soul and spirit, the self and the social aspect of existence’.

Violently coerced sexuality counteracts the expectation of pleasure linked with the potential of one’s own body. Inger Agger and Soren Buus Jensen note that the sexual imprinting of both the victim and the perpetrator are tied up in the psychodynamics of this interaction. The victim experiences the assault as an attack on her/his sexual perception of the body, aimed at destroying her/his sexual identity. A key component of this traumatizing and identity-destroying attack is the confusing sense of enforced collusion in an ambiguous situation that comingles aggressive and libidinous elements.

A matter of life and death

The narrative and experiential links between sexuality and violence oscillate between our opposing abilities to reproduce and kill on the one hand, and our understanding that we are always vulnerable and must ultimately die on the other. The inevitability of death as the ultimate expression of our sense of subjugation and powerlessness is countered by the real potential housed in the ability to kill and the imagined virility of being able to achieve immortality through generativity (in this case – reproduction).

In the eighteenth century, sexual ecstasy was frequently alluded to as ʻdyingʼ and orgasms as a ʻlittle death’. In the twentieth century, soldiers, who must always be prepared to kill and to die, reported the ʻsexual driveʼ they experienced in some extreme situations. Their descriptions illustrate how anger, displeasure, hate and horror can stimulate violence, and how the practice of excessive violence can trigger sexual arousal: ‘The experience seemed to resemble spiritual enlightenment or sexual eroticism: indeed, slaughter could be likened to an orgasmic, charismatic experience. However you looked at it, war was a “turn on”.’

Reports from soldiers have described the ‘wild joy of borderless inhibition’ triggered by a sense of commanding power over life and death. Their elation appears to be more than just a triumphant feeling of having escaped death, it is accompanied by the sense of having been liberated from all civilized norms and rules: ‘the perpetrator experiences unlimited sovereignty, absolute freedom from the burdens of morality and society in the suffering and death of the victim’.42

Camouflaged. Photo by EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid from Flickr.

Morality, society and regulation

The ʻburdens of morality and society’ – the civilizational achievements that confront the human subject in the modern era – focus on a re-positioning of violence and sexuality. The eighteenth century saw the establishment of a new ʻorder of knowledgeʼ and a historically unique construction of reality with ‘the human being as a self-empowered, organising subject’ at its centre. ‘Human beings as such did not exist before the end of the eighteenth century’. Violence and sexuality became human possessions: property to be released and controlled.

At the same time a dichotomy, that would come to characterize the modern era, developed between the public and private spheres. The public sphere is the locus for negotiating interpretations of reality, along with normative rules derived from them and expressed in the ʻorder of knowledgeʼ. In contrast, the private sphere promises an intimate space of individual freedom in which moral standards are a matter of choice. They may or may not be followed. Once established, this ʻorder of knowledgeʼ becomes self-perpetuating and professes to act as a guarantor of order, peace and security through self-evident practical constraints and a definition of what is ‘normal’.

Shifts in the discourse

One significant aspect of the modernization process was a fundamental shift in the discourse on violence. This change was launched by Machiavelli’s opening question: ‘When is violence called for and to what degree?’, and transformed by Thomas Hobbes’ deliberations on the logic and limitations of violence. Since the publication of Hobbes’ argument, physical brutality has been problematized in and of itself – a process that generates the idea that violence can only be considered legitimate if it serves to protect people from violence that is even worse. What develops is a concept for categorising violence into what is permitted, necessary or forbidden. Within this model, the state is granted a monopoly on brutality.

Closer inspection reveals that, in reality, the normative standard of renouncing violence – supposedly unanimous in public discourse – is only rudimentarily followed and implemented. Instead, real-world practices of violence are subjected to a range of legitimizing and rationalizing patterns that seek to bridge the gap between the normative standard and the actual practice. A man who brags to his colleagues over drinks that he beat a woman to within an inch of her life will, in all likelihood, alienate his listeners. If he claims to have ‘screwed a woman so hard she couldn’t take it anymore’, he can expect knowing nods of acceptance and recognition.

The use of violence as a legitimized means for creating social order and generating a sense of community and cohesion extends far beyond youth subcultures. The corporal punishment of minors was not outlawed until the year 2000, and rape within a marriage has only been a crime since 1997. In certain situations, violence and an inclination towards aggression are expressions of dominance and superiority. They carry positive associations as resources that enable us to assert ourselves. Behaviours that seem odd and contradictory at first glance, on closer inspection often demonstrate compliance with an implicit understanding that violence may be employed to establish a position of superiority. This is reflected in the case of GI Cooper, stationed in Britain as part of a supply unit during the Second World War. His story runs as follows: one evening he encounters a young local woman on her way home. She does not return his greeting. ‘Why won’t you talk to me?’ he asks. ‘All the other girls around here do.’ Cooper pushes the young woman into a bush at the side of the road, presses her to the ground and sits on her. ‘If you don’t let me get what I want, I’ll strangle you,’ he says. Then he rapes her. Afterwards, before releasing her, he enquires if she’d like to go to a dance with him the following week.

In order to get to grips with the heterogeneity of different practices of violence and legitimation strategies, Jan Philipp Reemtsma suggests that, in phenomenological terms, violence can be divided into three groups. Reemtsma speaks of locative, raptive and autotelic violence – but the categories can also overlap when violence is inflicted. Locative violence is intent on moving or removing a bodily presence standing in the way of achieving a goal (in battle, for example). Raptive violence seeks to overpower a body so it can be used, primarily in a sexual sense. Autotelic violence destroys for destruction’s sake, pure and simple. The first two forms of violence are linked to instrumental aggression and it can be assumed that they are based on a means to an end strategy. They are underpinned by the logic of reaping benefit from an act that, while comprehensible in view of its overriding goal, must be condemned for the means chosen to achieve it. In cases of locative and raptive violence, the perpetrator initiates an interaction with the victim that leaves vestigial scope for a reaction. Such acts of violence are not legitimized, but they are ʻunderstood’ – which can entail ‘understanding’ the perpetrator. Meanwhile, the victim may be assigned part of the blame for the interaction (and often is). A woman who has been raped may be imputed to have goaded the perpetrator into committing the assault, or else someone ‘standing in the way’ may be accused of being careless or in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Autotelic violence cannot as easily be labelled an ultimately explicable act, or indeed a phenomenon that can be managed with penalties or ostracism. Take, for example, the debates surrounding the mysteriousness of the fact that ‘completely ordinary men’ are capable of autotelic excesses of violence. These discussions might be read as an attempt to escape the horror and confusion this form of violence generates. They may be trying to evade the troublesome fact that such events were never limited to the pre-modern era and remain rampant in the twenty-first century – despite expectations that people who commit autotelic acts of brutality should be penalized, or the fact that anyone could be a victim. Perhaps these arguments also aspire to revive the idea that such acts are essentially pathological. Jan Philipp Reemtsma cites Alexander Mitscherlich’s response to accusations that his criticism of the German medical community under National Socialism denounced an entire profession because of a few insane, cruel monsters: ‘To understand a crime of this magnitude we cannot resort to the assumption that it was committed by a few crazy sadists – there are just not that many out there’.

Reemtsma pursues his case as follows: ‘Just as absolute political power manifests itself in the ability to eviscerate and exhibit bodies, absolute individual power manifests itself in autotelic violence – unrestricted power that pursues no other end than itself.’ This ability to exercise unrestricted power seems to hold the promise of an advantage that is both fascinating and absolute. It offers freedom to men ‘who no longer have to let a woman, or a moral sense of guilt, hold them back when the time comes to make people tremble with terror. “Beyond good and evil at last!” Finally, for once, to be a man – the inhuman superman!’

The ‘collective singular’

The term ‘collective singular sexuality’ developed as part of a modernization process in which violence too was resituated. Modernity saw the displacement of religion as a meaningful, normative authority, while culturally integrating and absorbing bodily experiences and activities that had previously led an ʻundefinedʼ coexistence, sexualizing and socializing them. If society in the Middle Ages was characterized by an inconsistency of sensibility and behaviour, the needs and reactions of people in the modern era were increasingly normalized and adjusted to meet the demands of new production methods. Abnegation, adaptability, austerity, discipline, reliability, serviceability and self-control all complied with a new, coveted social character, designed and formed less by external force than by self-regulation techniques individuals could learn. To comply with the demands of civil society, the modern subject felt compelled to supervise and observe her or his own feelings, affectional drives and needs, with the objective of controlling them so as not to be overwhelmed.

Sigusch describes the modern ‘objective of sexuality’ as ‘fixated on lust yet anti-erotic, simultaneously intimate and public, a belief in science, petty, denunciatory, hypochondriac, improving and corrective, both degradative and constructive, procreative, chastening, encompassing and totalising’. If this is right, it shows how the modern era’s demands descend on the individual to encourage both self-hate and an abnegation of lust. Social burdens come to be imposed both in terms of control (demographic policies, eugenics, medicine) and instrumentalization (the alignment of personal sensibilities and needs with new demands and processes at work and in the military).

Modernity has made sexuality a product of learning, subject to social control throughout the genesis that brought forth the new order. The focus of this new order has been on the erotically charged nuclear family, responsible for ensuring compliance with the ban on sexual acts involving children; on procreation as the only legitimate goal of sexual activity; on state regulated and controlled child rearing; the militarization of young men; the rationalization of as many areas of life as possible; and on the definitive power of medicine.

Since this transformation, the debate around sexuality has been subject to a paradox that exerts influence to this day.

On the one hand, unremarkable, ‘normal’, ‘psychological’ activities were granted a degree of importance and injected with a level of lust that exploded both the old order and the insistent, never-ending conversation about sexuality. Over the course of the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, all that isolating, observing, investigating, recording, transgressing, sinning, confessing, admitting, systematising, analysing, training, advising, treating, codifying etc. enlarged and inflated sexuality. Sex became massively overrated. It was imbued with symbolic and real meaning and granted a power over people that can only compare to that of material goods and money fetishes. Equally, anything erotic, arousing and sexual was suppressed and rendered taboo. It was forbidden and subject to punishment, never to be named. There developed a paradox of simultaneous emphasis and suppression, of encouraging that which is frowned upon, propagating that which should disappear, airing self-induced experience in public. It is a paradox in effect to this day, though in a more refined form. This creation of appealing, yet forbidden, repressive obsession, this interweaving of obliterating prohibition and generated demand, places the sexual sphere in permanent spotlight, creating an insatiable potential for conflict.

At the moment of its conception, the civil form of sexuality became a ‘monstrous construct of sodomy/delinquency/guilty pleasure/dysfunction/illness’. The spectre of onanism dominated debate in the eighteenth century. Later, in the nineteenth century, ʻperversions’ –specifically homosexuality – took centre stage. ʻSexual dysfunction and gender identity disordersʼ became the focus in the twentieth century. Today, concepts of de-gendering and gender blending have been called upon to take control of the potential for conflict inherent in the concept of sexuality. It is a control exercised through normative standards and, not uncommonly, through medically induced forcible violations of the body.

Male fantasies

The idea of the gender binary, expressed in a female and male body is, persistently hegemonic and naturalistically conveyed, as Thomas Laqueur demonstrated, is an idea born in the late eighteenth century. It replaced the earlier notion of a single sex and generated a new definition of the sexual nature of human beings. The one-sex model of the body had been based on the idea of a completely developed, superior male and an incompletely developed female counterpart. Without relinquishing the theory of male dominance, this concept was replaced by a notion of complementary gendered bodies equipped with correlative reproductive functions.

Corresponding male and female gender characteristics were thought to be derived from complementary gendered bodies. These characteristics destined the two genders to labour either in the public domain (men) or in the private sphere (women). The hierarchically ordered patriarchal pair was represented in terms of a vulnerable, inferior, dependent woman and her cosmopolitan, autonomous, male protector, with his capacity to inflict injury. However, since the human being – whether imagined as female or male – fails to flourish in this harmony of complementarity, gender constructs can only be enforced in real life through considerable normative constraints, differentiations and de-realisations. Gender identities assigned qua biological sex must be laboriously acquired. The process is never-ending. The ʻqualitiesʼ associated with them must be on constant display (the man – superior, independent and potent; the woman – desirable and accommodating). Any desires and needs that run counter to declared gender identity are consequently repressed and suppressed.

In her Philosophical Investigation of Rape, Louise Du Toit vividly describes how comprehensively the construct of a harmoniously complementary gender binary hides the violence and exclusion that must be employed to relegate the female gender to the private sphere. This then reserves the public sphere, with its prerogative of interpretation and political decision-making, exclusively for the male gender. In daily life, the use of violence and sexuality to uphold this gender order is a matter of course. This is a fact revealed in the extended hesitation that preceded the legal sanctioning of rape within marriage, as much as in a glaring willingness to overlook what is plainly visible.

You forgot the colour film

High stood the sallow thorn on the beach of Hiddensee

Micha, my Micha, I was in so much pain,

The rabbit timidly peeked out of the tree

My pain cried so loud into the sky-blue!

So angrily my naked foot stomped the sand

And from my shoulder I knocked your hand

Do that again Micha and I’m off

You forgot the colour film, my Michael

Now, no one believes us, how beautiful it was here – ha, ha!

You forgot the colour film, by my soul

Everything was blue and white and green and later it wasn’t true

You forgot the colour film, by my soul

Everything was blue and white and green and later it wasn’t true

Now I’m sat at home

Picking out photos for the photo album

Me in bikini and me in the nude

Me in sassy mini-skirt and a landscape too – yeah

But how awful, the tears run hot

A landscape with Nina and it’s all just black and white

Micha, my Micha, it all hurts so much

Do that again Micha and I’m off

You forgot the colour film, my Michael

Now, no one believes us, how beautiful it was here – ha, ha!

You have forgot the colour film, by my soul

Everything was blue and white and green and later it wasn’t true

You forgot the colour film, by my soul

Everything was blue and white and green and later it wasn’t true

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_L9b2ifwqlQ

In 2017, for example, the Cologne rock group AnnenMayKantereit covered Kurt Demmler’s hit single You forgot the colour film – a well-known song from the former GDR, first performed by punk artist Nina Hagen in 1974. The much-loved singalong hit was read as a coded protest and a subversive critique of consumer shortages and travel restrictions in communist East Germany. It wasn’t until the release of the 2017 cover version that the lyrics were interpreted as a description of sexual violence. Reading the words, this interpretation strikes me as unambiguously correct. Friends from the former GDR have argued that this was an allegorical protest song; I nevertheless hold that it is worth reflecting on whether the lyrics support the reading that the song is in fact about violent sexual abuse.

Deconstructions

The 1968 revolution failed to dissolve the gender dichotomy. The liberation it sought in fact promoted sexual promiscuity for the benefit of men. ‘If you sleep with the same person twice, you’re part of the establishment’, the saying went. At the same time, women began to call for self-determination over their own bodies in response to the unreasonable demand for availability placed on them. The effect has lasted. Women probed male self-representations and self-heroizations for violent content. The slogan ʻthe personal is politicalʼ launched a process that opened a public debate on sexual abuse and violence, previously hidden in the private sphere. It also provoked a discussion on a fixation with the penis and virility in representations of male sexuality. Men, who ‘have at their disposal a highly significant sexual organ but not a sexual body that can be occupied’ were confronted with the limited space they had conceded to the desires of women. They now had to face their indirect response to ‘the heterosexual man’s fear of femininity and his difficulty in yielding as an object of desire’. The debates, begun in the 1980s, surrounding the possible deconstruction of socially, historically and culturally formulated sex/gender definitions, disturbed the gender binary, which is so consistently discriminatory towards women.

Nevertheless, it has become clear that the original concept of self-liberation through radical challenge was not necessarily effective: ‘though not currently the case, in theory “sex” can be conceived of without “gender”. The reverse, however, does not apply. An irreducible “remainder” persists with a materiality of its own which, though it can be pictured, cannot be intellectually conceived.’

Thus, citing Hegel, Sigusch argues: ‘the autonomous citizen remained disunited with reality and the “sighing” continued. The misery of life did not disappear, people did not lose their sense of the “uneasiness in culture” of which Sigmund Freund would later speak (1930). And so, they dragged themselves from one sexual revolution to the next for more than one hundred years, always hoping that life would begin.’

Gunter Schmidt, on the other hand, sees light at the end of the tunnel. The ‘self-determination discourse’ of the 1980s rendered homosexuality ‘normal’, he notes. Subsequently being gay came to be perceived merely as one of many lifestyles once classed as ‘perversions’. The only forms of sexual behaviour to retain the perversion label were those with a demonstrable power imbalance between partners. The deconstruction of traditions around sexual, romantic and family relationships led to a ‘home in plurality’, in which ‘sexual preferences and orientations, types of relationships, forms of child rearing and cohabitation, versions of masculinity and femininity’ were no longer prescribed, but negotiated on the basis of a ‘consensual morality’ – a narrative borrowed in no small measure from feminist debates.

Irrespective of these developments, it should be noted once again that theoretical work in this field has produced little in the way of a systematic understanding of the relationship between sexuality and violence – a shortcoming which also afflicts the field of theory on sexual violence. The substantial body of knowledge that relevant studies have provided only emphasizes the continuing prevalence of sexual violence, which cannot as easily be classified as a ‘perversion’ that deviates from our ‘de-traditionalized’ perception of normality.

#MeToo: Tell it!

Tell it in Spanish

In Sign Language

Tell it as a poem

As a play

As a letter to President Reagan

Tell it as if my life depend on it …

Tell it as a court case

As a congressional debate

As if the power of children

were respected

Tell it as domestic terrorism

As a national sport.

Tell it as a jump-rope game …

Tell it as graffiti

As a religious service

Tell it as a classified ad …

Tell it as a TV commercial

As a science experiment

As a country western song.

Tell it as ancient history

As science fiction.

Tell it in your sleep …

Tell it as a map of the world

As if I were still forbidden

to speak the words …

Tell it so it will never happen again.

Emily Levy

In the 1970s, the women’s movement used its ‘speaking out’ strategy as a countermeasure to the ignorance around forms of sexual violence that were omnipresent and routine. Speaking out encouraged women to talk about their experiences in public, from their own perspectives, and to wrest back control over the authoritative interpretation of these experiences. Bearing in mind the difficulty of expressing women’s traumas in words, the feminist strategy proved effective (despite its shortcomings) in counteracting isolation, rendering the shared gender-political context of individual experiences visible, and effecting change in national and international law.

Reviving the policy of ‘speaking out’, as part of the #MeToo debate, may yet counteract the overly optimistic take on the current zeitgeist, that Gunter Schmidt, for example, endorses. It could also prevent the experience of sexual violence from being once again marginalized as a problem to be solved in private. In response to misgivings that public shaming tosses the baby out with the bathwater and threatens flirtatious banter between the sexes (an argument which seems bizarre in view of the ‘cases’ up for debate), one could argue there is more at stake here than just sanctioning intolerable forms of violence.

Fighting to end such practices goes hand in hand with the right of women to sexual self-determination, and the human prerogative of taking pleasure in one’s own desires and intimacy, rather than serving the urge to fixate on the link between sexuality and violence – even if the fairy tale that ‘the lady doth protest too much’ continues to remain firmly and persistently entrenched.

Thanks to Regina Mühlhäuser for a critical review of this text and valuable suggestions.