Ekphrasis on the edge of catastrophe: why literary descriptions of works of art allow the world to reappear; people of the sea, people of the land: on the cosmopolitanism of sailors; and what AI means for the Welsh language.

‘Sometimes, there is a sense that one has reached the end of the road,’ writes Mererid Puw Davies in Welsh journal O’r Pedwar Gwynt – a sense that the language and ideas that have led us thus far have been exhausted; and that before us we see only a wall or a cliff edge. In such times, the capacity simply to describe something can be an advantage, Puw Davies writes, recalling the words of W.G. Sebald: to describe a disaster offers the possibility, at least, of overcoming it (Die Beschreibung des Unglücks, 1985).

‘Sometimes, there is a sense that one has reached the end of the road,’ writes Mererid Puw Davies in Welsh journal O’r Pedwar Gwynt – a sense that the language and ideas that have led us thus far have been exhausted; and that before us we see only a wall or a cliff edge. In such times, the capacity simply to describe something can be an advantage, Puw Davies writes, recalling the words of W.G. Sebald: to describe a disaster offers the possibility, at least, of overcoming it (Die Beschreibung des Unglücks, 1985).

Puw Davies revisits Birgit Pausch’s long-forgotten novella Die Verweigerungen der Johanna Glauflügel (1977) and reflects on the narrator’s use of ekphrasis – the description of artworks, in this case Diego Velásquez’s Las Meninas and Donatello’s Maddalena Penitente. If Johanna Glauflügel does not have the words to make sense of the strange world she inhabits, ekphrasis ‘allows the world to appear again, as in a bright mirror, in the peculiar dawn of the familiar and the unfamiliar’.

Land and sea

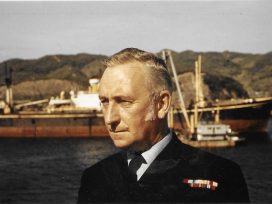

Reading the works of Horatio Clare and Marseillaise crime writer Jean-Claude Izzo, Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan remembers her 1950s childhood in north Wales, as a daughter to a merchant navy sea captain. She recollects the collision of two worlds, how her father would have difficulty adapting to life on dry land; and how other children’s fathers, who were mostly quarrymen and farmers, would have arms free of tattoos and no golden ring in one ear, ‘like a gypsy’.

Titles such as The Mālim Sāhib’s Hindustāni (1921) and Arabic for Seamen were placed next to Welsh-language literature on the family bookshelves; and after her father had returned from sea, whilst her neighbours would be spreading butter on their bara brith (traditional Welsh fruit bread), she would be tasting turrón from Spain and panettone from Italy.

Today, she understands her father’s loneliness: as Izzo writes, ‘land is the only reality for mankind; and it is only on land that we may come to know sailors – unless one sails one day on a cargo ship.’ Would Wales have voted for Brexit, Lloyd-Morgan reflects, had more Welsh men followed her father’s career path?

Language and AI

The Welsh-language intellectual community has tended, historically, to reserve philosophizing on the ‘big’ questions for the English language, and to participate in those discussions according to those terms, writes Morgan Owen. The emergence of AI adds another dimension to this problem. This old habit of adapting the English world-view could mean giving precedence to an external subjectivity, Owen argues. From time to time, one needs to disbelieve the material maps provided. The transcendent is not a retreat but a celebration of an increasingly rare quality in our world: subjective consciousness.

Also: Aled Jones Williams on the religious language of Morgan Llwyd (1619–1659); photographer Chloe Dewe Mathews follows the footsteps of Frankenstein; and personal responsibility in the time of Covid-19.

More articles from O’r Pedwar Gwynt in Eurozine; O’r Pedwar Gwynt‘s website

This article is part of the 9/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter, to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing

Published 22 May 2020

Original in English

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

‘A decisive effort is necessary’

Heritage, Brexit and the British state

The case for Brexit may amount to more than pure fiction. But there is no denying it is rooted in a revivalist narrative of British history. Whether the perceived enemy be Europe, the welfare state or migrants, the right has been waging the same battle since the 1980s.

The language of languages

Wespennest 179 (2020)

In ‘Wespennest’: how Austria’s historically multilingual literature has been complemented by a range of idioms from beyond the former Empire; and why Europeans should reclaim English as the Franco-Germanic hybrid that it is.