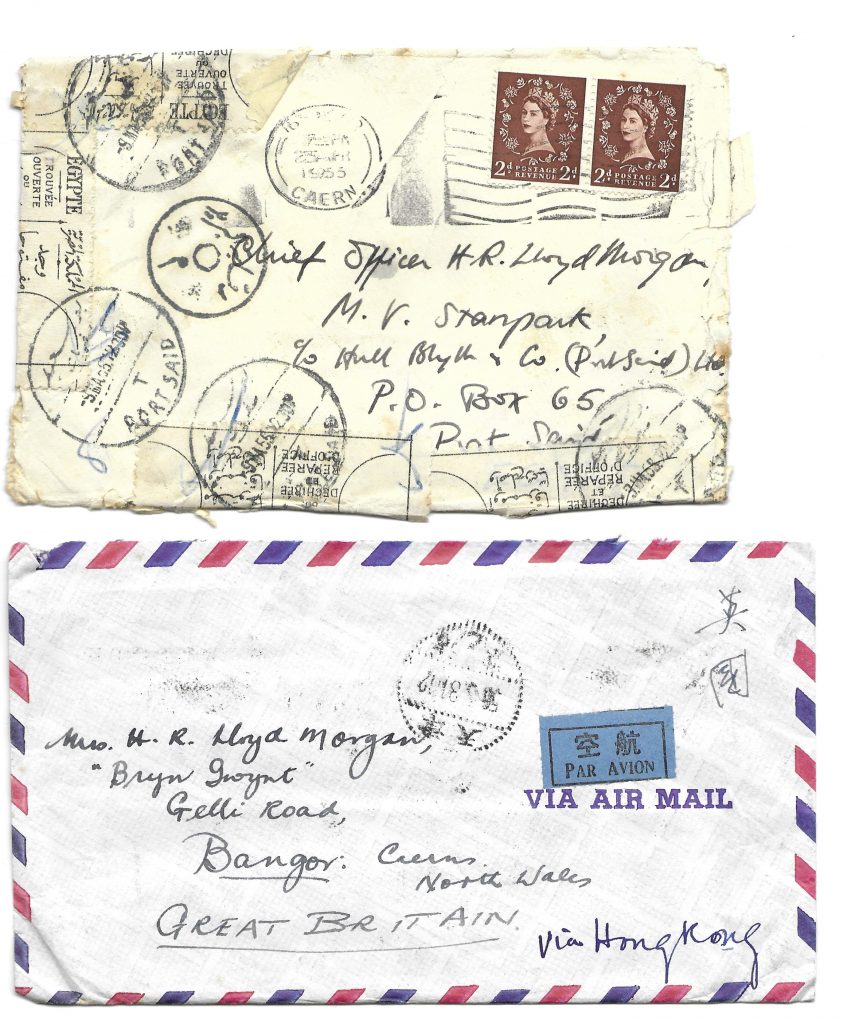

From my early childhood I was all too aware that my father, a captain in the merchant navy, spent more of his life living and working in a different world from us land-dwellers at home. As I grew up, I began to understand how difficult it is for sailors to maintain a relationship with their families, and how great the gap is between their two worlds.

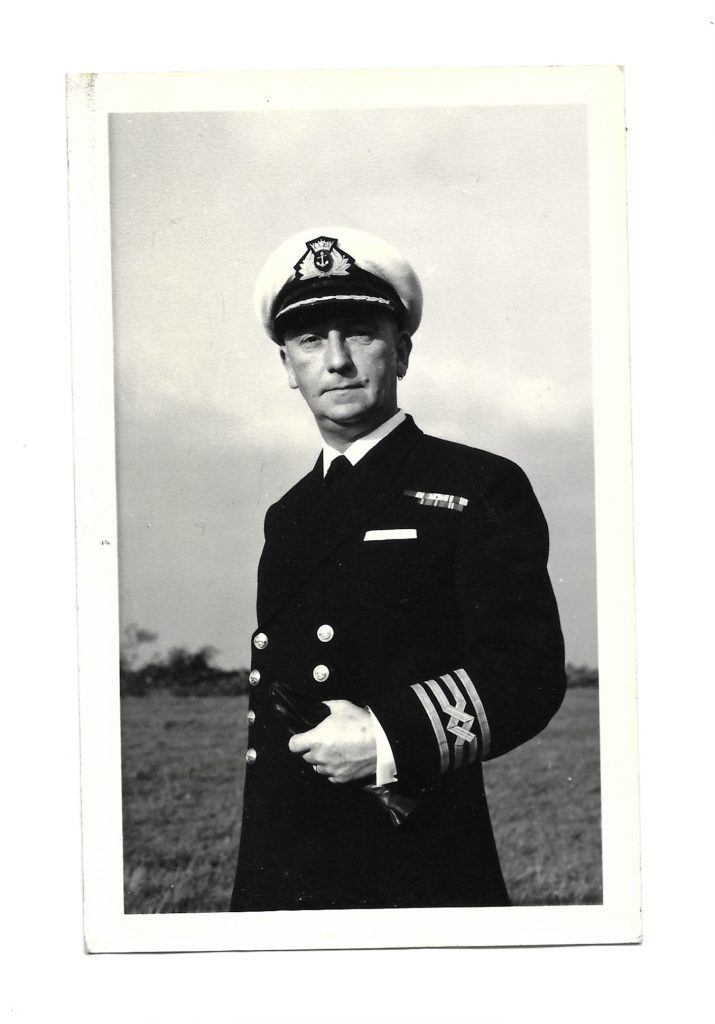

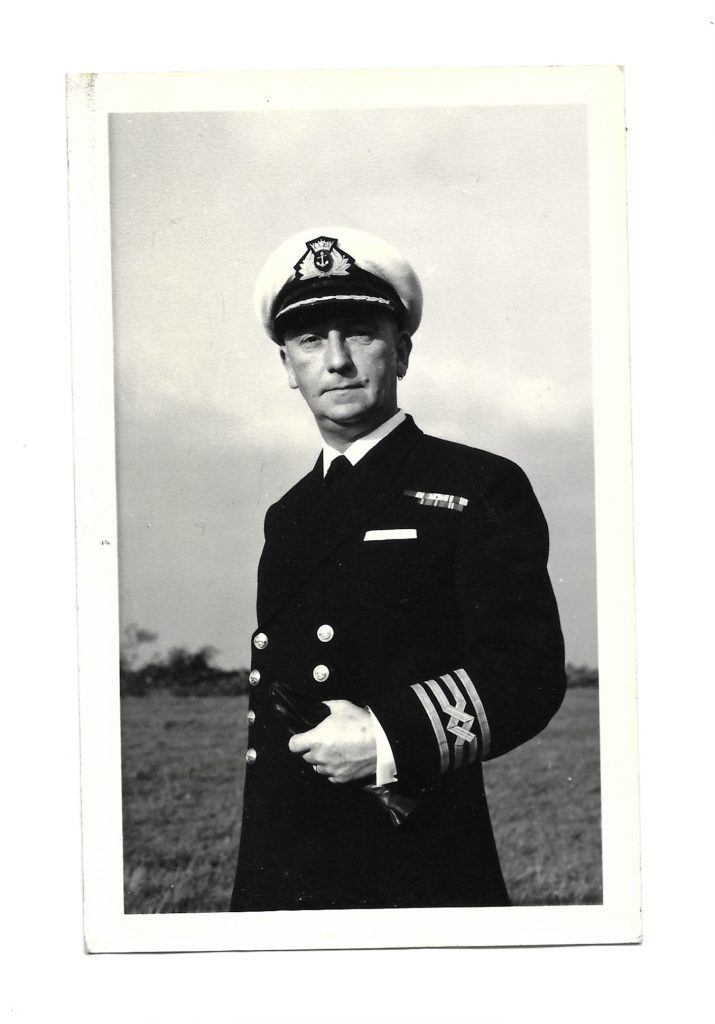

The author’s father in 1968. Private archive, copyright.

Jean-Claude Izzo, the French author from Marseille, describes this unbridgeable gap to perfection in his novel Les marins perdus (‘The lost sailors’, 1997). The difference between life at sea and life on land is intensified, he notes, by the close cooperation that is essential onboard. There, working together through major crises creates a tightknit community of individuals who depend on each other in order simply to survive from one day to the next. The only way that those on land can even glimpse this hidden world, Izzo writes, is to become part of it:

at sea a storm will weld the crew together. Sailors can never explain those moments to their families … Because they would only worry. And also because it is impossible to explain. The storms don’t exist. Neither do sailors once they are back at sea. The land is humanity’s only reality. And in any case, it’s only on land that we can know, can get to know, sailors. Unless one day you too board a merchant ship.

One of the few contemporary British authors to write about the experiences of sailors on merchant ships is Horatio Clare, who ironically spent his formative years in landlocked Breconshire, in Wales. He spent some months as a ‘resident writer’ on two large container ships belonging to a Danish company and recorded this experience in Down to the Sea in Ships: Of Ageless Oceans and Modern Men (2014). He describes the book as ‘partly the report of an observer and partly the story of a participant … one of the ship’s company but not one of the crew’ and stresses how the sailor’s world is invisible and completely alien to the rest of the population, even though we landlubbers are utterly dependant on their work:

Just beyond the horizon there is another world. It runs in parallel with ours, but it obeys different laws, accords with a different time and is populated by a people who are like us, but whose lives are not like ours. Without them, what we call normality would not exist. Were it not for the labours of this race we could not work, rest, eat, dress, communicate, learn, play, live or even die as we do.

Here and in the companion volume, Icebreaker: A Voyage Far North (2017), Clare explores the constants in the age-old experience of sea-borne travel and work through quotations from English and French writers of the past, while at the same time giving a vivid impression of the reality of life onboard today. He does not gloss over the discomfort, the stench of diesel and constant engine noise, the long hours, the ever-present dangers, from terrifying storms to dangerous fires, and the strain on everyone, especially the Master and officers, who are responsible for everyone’s safety, as well as that of the millions of pounds’ worth of vessel and cargo.

This article was first published in Welsh in O’r Pedwar Gwynt 1/2020. Read a review of the issue.

My father certainly felt the stress, especially in the years leading up to his retirement, when he commanded giant tankers or VLCCs (‘very large crude carriers’). This only compounded the difficulties of combining his maritime career with marriage and family life. It’s no wonder that problems arose. With her husband often away for a year or more at a time – his longest peacetime absence, in the 1950s, was 27 months – my mother was to all intents and purposes a single parent, bringing up three children on her own. She had to do things that were then considered men’s work: mixing cement, chopping and sawing firewood, changing an electrical plug or replacing the washer on a leaking tap, while at the same time following her own career as an entomologist at the University of Bangor.

When the Captain came home, life was turned upside down. He could not shake off his role as the boss, and as children we were confused by the new set of rules that would suddenly be imposed upon us. He found it hard to adjust from the completely masculine world on board ship to the more ‘female’ world of home and family, and he did not cope well when his image of a perfect, harmonious family came up against reality. Like a prisoner released at the end of his sentence, he was bewildered by the social changes that took place during his long absences, and he was never at home long enough to make new friends. His only close friends in the neighbourhood were one or two old wartime comrades and an old classmate from secondary school days.

At sea, the captain’s life can be lonely, for he has to keep his distance from the crew, but life at home could be lonely too, and the whole family suffered. As an adult, after meeting other people who were also children of ocean-going sea-captains, I began to realise that my own experiences in this respect were in no way unusual.

The maritime history of Wales extends back to the earliest time, as a recent book Wales and the Sea: 10,000 years of Maritime History (2019) has emphasised. However, as all too often, the importance of merchant shipping in the socio-economic history of Wales during much of the twentieth century is overshadowed by the history of the preceding centuries. Today, few people are aware of Welsh seafarers’ role in their home areas and the tight networks they formed, especially in coastal villages like Llangrannog, whose strong sea-going tradition continued well into the second half of the last century.

There was no seafaring tradition in our family, however. It was purely by chance that my father was brought up in Cardigan after his father was appointed manager of a bank in the town. But living in a district where so many men down the generations had gone to sea to earn their living, he too caught the bug. In 1937, as a lad of sixteen, he refused to follow in his father’s footsteps and instead joined his first ship as an officer cadet. As the years went by, he passed his exams and moved up the ranks until, at 33, he embarked on his first voyage as a fully-fledged captain in command of his vessel.

One night a couple of years later – I was a very little girl at the time – I got out of bed and sneaked downstairs. My parents were sitting at the kitchen table and on the table in front of my father were two stacks of banknotes. I had never seen so much money before. My father explained that the biggest pile contained £100 and the other a little less. That money must have been his earnings, probably a bonus payment, at the end of one of his voyages. I realise now that this sum was equivalent to about a tenth of the price my parents had paid a few years previously for their house on the outskirts of a village in north-west Wales, quite a substantial property with a big garden. Those banknotes represented a lot of money in the mid-1950s and would have made a significant contribution to the local economy, since at that time a large proportion of that sum would have been spent in small businesses in the village and nearby towns.

And my father was not the only sailor in the district. Compared with parts of Cardiganshire or Pembrokeshire, there was no strong tradition of seafaring locally, but there were other captains living within a twenty kilometre radius, including two who at different times worked for the same company as my father. In the mid-1950s the majority of the captains employed, like he was, by the Stanhope Steamship Co. Ltd of London, were Welshmen – one, Dewi Rees, was an old school friend – and four of the others had settled in Wales.

The author’s father’s ship, The Alva Star, in 1972. Private archive, copyright.

When the age of the giant oil tanker arrived, the first British captains appointed to command them were Welsh, my father among them. Merchant-ship owners were said to prefer Welshmen as commanders of their vessels because they were ‘prepared to go anywhere, with any cargo, with any crew’. These men took Wales with them to the world – and brought the world to Wales. It is tempting to speculate that if we still had as many ocean-going mariners, the political history of Britain during these last few years might have been very different.

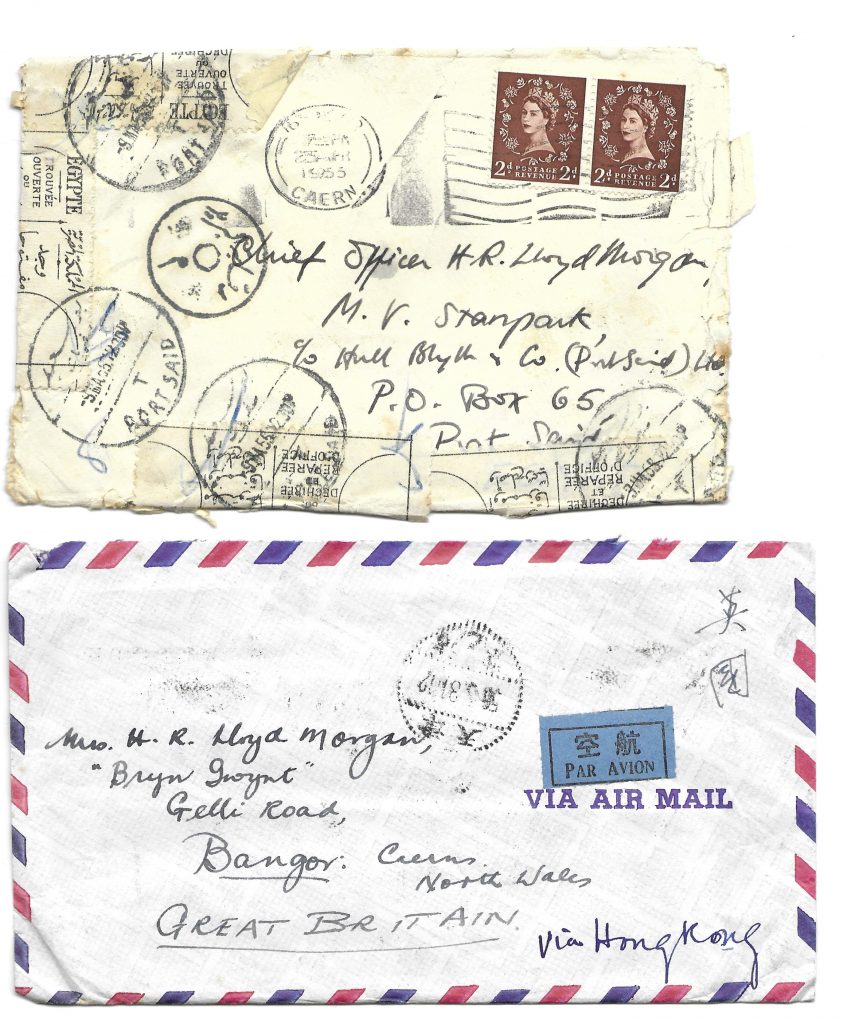

The letters my father wrote to members of the family reveal how proud he was to be both Welsh and internationalist in outlook, of being able to work and socialise with people of all nations, whatever their language, religion and culture. He was always keen to learn more about their way of life, whether it was through trying unfamiliar dishes in restaurants, attending a concert of traditional music and dance, or leaping at the chance to experience a traditional Japanese bath.

The presence of that wide world beyond ours became part of our lives in our north Wales village: in the postcards, the foreign stamps and the tales he told in his letters or when he was home on leave. It was there by my bed, in the camels striding across the Egyptian mat bought in Port Said, in the brass candlesticks from India that stood on the mantelpiece, and in the treats his overseas friends and colleagues would send us at Christmas. It’s strange to think that in the 1950s we would be wolfing down turrón from Spain and panettone from Italy while our neighbours were sedately buttering their slices of bara brith, the traditional Welsh currant-bread. I still have a Bulgarian picture-book about traditional costumes which the shipping agent in Varna (Stalin in those days), himself the father of two daughters, sent as a present for me and my sister.

From early childhood, we were aware that beyond our own horizons there were different countries and cultures and countless other languages. Being bilingual from childhood would have been a great asset to Welsh sailors, and my father certainly picked up new languages without fuss or difficulty. Even if officials and ships’ chandlers or repairers had some English, if he felt he was being fobbed off or cheated he usually found that challenging them in their own language was far more effective. ‘Thank goodness my Hindustani is coming back’, he wrote from India in 1956, after using it to ‘kick up hell’ with those who had supplied and fitted defective shackles on board his ship.

In the study at home there were shelves devoted to dictionaries and specialised phrasebooks with titles like Arabic for Seamen and The Mālim Sāhib’s Hindustani, to facilitate communication with other seamen – and sometimes the police. In 1939, with war only a few months away, my father, then seventeen years old, had a chance to practise both German and Dutch when his ship docked in Surabaya, Indonesia. On the quayside he met a gang of young German sailors and joined them for a night out, drinking and enjoying the local Reistafel. Then on they went to sing ‘God Save the King’ outside the German consulate and ‘Deutschland über Alles’ outside the British one. Pursued by the outraged officials of three nations, they were caught sauntering back to their ships and thrown into the police cells, where, he added, they spent the rest of the night having a bilingual cymanfa ganu – a very secular version of the traditional Welsh hymn-singing festival.

From the letters he wrote in the 1950s it is evident that getting to know other countries, languages and cultures, and adapting to them, strengthened his consciousness of his Welsh identity and his pride in not being English. In 1956, after docking in Poti, in what was then Soviet Georgia, he noted with satisfaction that the port officials were very friendly towards him because, as they told him, he was ‘different from the English captains’. During the early years of his career, when he had to spend time in Liverpool on training courses or sitting his exams, he would always stay with a Welsh-speaking family who had settled across the Mersey in Birkenhead.

Private archive, copyright.

Time and again his letters reveal the strength of the close-knit band of Welsh seamen who would meet by chance from port to port or would exchange messages over the radio when in reach. Once, instead of a conventional message, he received an englyn, a short poem in a traditional Welsh strict-metre form, sent by Captain Jac Alun Jones, a gifted member of a famous family of poets. With another Cardiganshire man he spent the evening discussing the much-dreaded canhwyll corff, the ‘corpse candle’ said to foretell an imminent death; and in a Middle Eastern port he took on board a Welsh-speaking pilot, who asked him to chat to his wife in Welsh since, apart from with her husband, she had no one else to talk to her in her native tongue.

The letters also give a glimpse of the friendships that developed between the Welsh seamen and people of other minorities. He recounts discussing the Breton language with a pilot in St Malo, exchanging words that are similar in Welsh and Breton, and enquiring where the best Breton was spoken. During the Spanish Civil War his sympathies lay firmly with the losing, republican side. His closest seagoing friend in the 1950s was his colleague at Stanhope’s, Captain Ituarte, a Basque who had gained his first command at an exceptionally young age, thanks to his exploits in breaking General Franco’s blockade. Ituarte took British nationality and settled with his wife in a suburb of Cardiff.

Despite his pride in his Welsh identity and the affinity and sympathy he felt for other smaller nations, my father was a staunch supporter of the British state and indeed the empire. He was appalled when colonies began to demand independence after the war. I would guess that his political ideas were largely formed during his wartime service, when he was still young and impressionable. He celebrated his eighteenth birthday seven weeks after the UK declared war on Germany in 1939 and, like many merchant seamen, was transferred to the Royal Naval Reserve for the duration of hostilities, serving on naval ships. After serving in the Far East and elsewhere, he spent the latter years of the war as a lieutenant on the North Sea convoys, including a period aboard the corvette HMS Guillemot. One of his predecessors as an officer on that ship was the author Nicholas Monsarrat, who drew on his experiences on it in his novel, The Cruel Sea(1951), adapted for cinema in 1953.

When my father returned to civilian life and the merchant fleet in 1946, he remained a naval reservist and appears to have been recruited by Naval Intelligence. I only learned this in recent years, when, after my mother’s death, I began reading through her surviving correspondence with my father. Not long before she died, long since divorced, she had shown me the drawerful of bundled letters and entrusted me, as a professional archivist, with deciding what to do with them. I was shocked to discover among those letters a copy of a confidential report evidently submitted to the British government, describing his visit to the Bulgarian port of Stalin and reporting on the friendly shipping agent who had sent me and my sister that wonderful book on traditional costumes.

In the report, my father undertook to continue to send similar reports from Communist countries. Now I began to realise the significance of certain cryptic comments concerning ‘a copy of a certain report of mine on Tsingtao [Qingdao]’, or ‘having a job to do’ after being visited by a naval official when docked in a Canadian port, or handing over a document to the authorities in Aden, then still a British possession. He sometimes sent copies of these reports to my mother for safe keeping, making sure they were concealed within the pages of his innocent-looking private letters. Sometimes he asked her to send a document on to an Admiral Inglis, whom I now discover was the head of British naval intelligence at the time. I do not know whether some of those reports would be in code, but he was certainly well versed in coding and decoding messages, not only from wartime service but also as a commander of merchant ships. All messages between him and the shipping company were sent in code: in one letter to my mother, he describes being so exhausted on one occasion that in the middle of composing one message he fell asleep for two hours, his head on the open code-book.

It is not clear how long he continued to send his confidential reports to the admiralty, but he was certainly still a naval reservist in 1967. Some years later he mentioned casually that at the outset of the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War, he was crossing the Atlantic with a cargo (on a ship registered outside the UK) when he received orders from the Admiralty in London to report immediately to a naval base in Canada and stand by for further instructions, presumably in case the situation should escalate further. My mother was furious that he had not told her at the time, but he shrugged and gave a cryptic reply. Perhaps because I was there? Or because he was not supposed to tell her?

Reading through my parents’ correspondence now, I have learned far more about his life and understood better how his career shaped our lives too. As I was growing up, I often felt uncomfortably different from other children. Had we been living in a village like Llangrannog, we would have been only one of many sailors’ families sharing the same experiences. But in our inland-focused village, we did not belong to the same world as our neighbours. Ours was one where my mother would vote on my father’s behalf in elections, where the pharmacist might phone to ask us if our father was home on leave and could spare some quinine tablets, for the local stock had run out and somebody needed them urgently.

Other children’s fathers came home from work every day and sat down to supper with their families, and quarrymen and farmers didn’t have tattoos on their arms, let alone wear a gold ring in the ear ‘like a gypsy’ – this said in a mocking tone. If he was laid up in port for some weeks and we went to stay with him on board ship, our experiences were so far removed from the everyday life of our village as to be incomprehensible to our friends and of little interest to them: our shoes dusted yellow from the remains of a cargo of sulphur; an Indian steward picking me up and carrying me on board when he realised that I was frightened of falling off the shaky gangway and down into the filthy waters of the Manchester Ship Canal; or watching bearded Arabs hammering at the deck to remove the rust.

The author’s father in 1968. Private archive, copyright.

How could we explain to people who thought that going to stay on a ship must be an exciting adventure that our lodgings were pretty uncomfortable? (Though there were moments to relish, like the exciting discovery of a cockroach or two in our cornflakes.) Nobody understood that after a few days we would begin to feel restricted and longed for the freedom we had at home to run wild over the fields, climb trees and mess about in the stream. We were not allowed to go anywhere without one of our parents, for the docklands were full of unfamiliar dangers, not to mention dubious characters. It was in Cardiff docks that I saw a drunken man for the first time: ‘Oh, look at that funny man dancing!’ ‘Take no notice, come along now, don’t dawdle.’

During his career, which continued to 1981, my father witnessed the decline of the British merchant fleet. Companies like Stanhope’s had raked in the profits during the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War – there’s nothing like a war for creating work for merchant shipping. But by the 1960s more and more vessels were sailing under other flags and run by non-British owners. My father spent the last period of his career working for a shipping magnate called Boris Vlasov, whose business empire was divided for tax purposes into a number of smaller companies with offices in Monaco. Nowadays, few people from any part of Britain work on merchant ships. This part of the long history of Welsh seafaring, and how it affected life for those on shore, is almost forgotten.