Although the internet and social media have greatly accelerated the spread of news, there is less control of the news offered to the public. The planet has been transformed into a ‘global village‘, throughout which news is spread within minutes, yet written journalism is on the decline. News appears more in the form of comment and opinion, while internet portals have become the fastest carriers of news. The speed of the publication of news on the internet and its presentation as hypertext has attracted public attention yet only deepened the crisis of print media. The last decade has brought major changes to journalism, but with each passing year it seems that the news offered online increasingly aims at sensation and effect rather than truth.

The situation is no different in Kosovo. On top of the media change, however, comes a set of political factors. Political interests and financial profiteering in Kosovo have caused chaos in the media and turned online journalism into a sham. This, combined with unemployment, a weak economy and a political crisis, means that most news served up by internet portals attaches no importance to objectivity, but only to sensation. Under the tight control of political parties, online journalism in Kosovo has failed to perform its mission of representing the truth.

Cultural-political malaise

The war in Kosovo in the late 1990s and the delayed declaration of independence in 2008 posed many challenges for the new state. New in its government, its institutions, its public services, its economy and its culture, this state was also new in its media. Almost ten years of independence have not sufficed to stabilise the situation. The crisis in which the country finds itself was also evident in the parliamentary elections held on 11 June 2017, which despite the formation of electoral pacts, failed to deliver a coalition or party able to form a majority government. The people have had their say: they do not believe in the political parties that lead Kosovo, and they are tired of corruption and the scandals that marked previous governments.

While the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PAN), the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK), and Initiative for Kosovo (NK) are trying to make up the required number of MPs to govern Kosovo for the next four years, there is no promise of any great change in the economic situation, in education, health, culture, and so on. Economically, Kosovo has remained at rock bottom, and is among the poorest countries in the Balkans, with a frightening level of unemployment in relation to its population. Most families live on welfare or are supported by relatives living and working abroad. The health service is in a catastrophic state, and the hospitals do not possess the necessary resources to treat patients, whether because of the shortage of specialist staff, the lack of equipment and medicines, or because of the hygienic conditions.

Cultural life virtually does not function at all, because support for the arts is conditional on party allegiance. The fact that Kosovo comes 68th in the PISA rankings out of the 72 states in which tests were carried out, and that 131 university programmes were suspended because of a lack of qualified academic staff at the University of Prishtina and private universities, testify to the very low level of education in Kosovo. The Department of Journalism at the University of Prishtina also lost its right to accredit and will not be able to admit masters’ and doctoral students from autumn 2017. The media at once called for an explanation from the University of Prishtina, whose rector Marjan Demaj stated that ‘The main reason for the suspension of the programmes is that we do not have the staff. We are very restricted. In reality, we are mere dogsbodies, who are doing jobs beyond our level of higher education.’ Demaj, the Education Inspectorate, and the major national media have refused to verify and investigate abuses in the selection criteria for the recent vacancies for academic staff in the Department of Journalism (as in other departments of Prishtina University), because political interests are involved.

This situation has had a significant impact on the development of the media in Kosovo, which has been fraught with problems in every field. Television, the print media, and online media all exhibit almost identical shortcomings. Kosovo Radio-Television, which is subsidised directly by the government, receives more financial support than any other television channel in Kosovo, but in terms of its staff and the quality of its programmes it is the poorest in the country. Other channels are filled with Turkish and Spanish soap operas, and carry virtually nothing of any educational value. In the print media, Koha Ditore (Daily Time), which also has its portal, koha.net, is probably the most serious and least politically biased newspaper in Kosovo.

Investigative journalism, which should be a principal line of development for journalism in Kosovo, is virtually non-existent, apart from the programmes ‘Life in Kosovo’, ‘Zona Express’, and some investigations conducted by Koha Ditore, the portal Insajderi (The Insider), and the newspaper Zëri (The Voice). However, these investigations have mainly been superficial, and have not caused any anxiety to the political leadership.

The print media and the online media have failed to fight the corruption that has spread to every aspect of life in Kosovo. This failure is evident in the silence over the abuses committed by ministries and state institutions, the religious extremism that has spread throughout Kosovo, and the crimes, abuses, and corruption of individual politicians. The Kosovo media are not guided by the principle of free speech, but controlled speech. Their politics is manipulative, with the aim of attracting the clicks that bring them profit, and their purpose is disinformation, because of the interests of the political parties that finance them.

Political bias and revolving doors

The media in Kosovo are not independent, but are managed and directed by the political parties. This is shown by the allegiances of several journalists and former journalists to parties. The recent elections also exposed the political bias of many journalists.

The case that caused the most commotion and indignation among the public was that of Arbana Xharra, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Zëri, who, after investigating corruption in the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) – for which she was rewarded with several national and international prizes – shocked the public in June 2017 by joining the very same party. A similar thing happened a few years ago when Margarita Kadriu, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Kosova Sot (Kosovo Today), also joined this party. The former editor-in-chief of Zëri had no answer to those who had trusted her in the war against corruption, but as happens with everything else in Kosovo, it took only a few days for the matter to be forgotten. The reason for this is simple: journalism in Kosovo does not function independently of the political parties and nobody believes that a journalist might expose or even bring down a government that is mired in corruption.

Berat Buzhala, the director of Gazeta Express, the largest online newspaper in Kosovo, was a deputy of the PDK, which clearly indicates the allegiance of this portal.

Halil Matoshi, a journalist, writer, and political analyst who was once a well-known supporter and member of the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), joined the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK), issuing a pompous declaration that, just as he had once trusted the LDK Chairman Ibrahim Rugova, he now trusted AAK Chairman Ramush Haradinaj.

Dukagjin Gorani, a journalist, political analyst and one-time adviser to the prime minister and chairman of the PDK, announced that he had joined the Vetëvendosja [Self-Determination] party.

The journalist Milaim Zeka, also well known for his frequent criticisms of the political parties and the previous government, joined the Initiative for Kosovo (NK).

These are only some of the examples of journalists who have openly crossed over into politics, but there are plenty of others who, either openly or covertly, have worked for the benefit of these parties. Such hypocrisy on the part of journalists has destroyed trust in the media and quenched public hopes for a better future for the country. The number of Kosovans who have sought asylum in Germany and other European countries shows how weary of this situation most of the country’s citizens are.

The politics of online news: Fake vs. Fact

Kosovo boasts more than three hundred portals dedicated to the spread of fake or partially fake news, which are beyond the control of any institution. Few online journalists in Kosovo observe the Media Code, the sources of their reports are unverifiable, and speculation and personal opinion replace facts and data. Reports taken from other portals generally do not indicate their original source, and subject the public to disinformation and manipulation.

Online portals in Kosovo are of two kinds: daily newspapers that have also become web portals, and newspapers that operate only online. The most well-known portals in Kosovo are Express, Zëri, Kosova Sot, Infopress, Bota Sot, Telegrafi, Infokusi, Insajderi, Koha, Periskopi, etc. Most of these are either directed by people in political parties, or openly display their political bias.

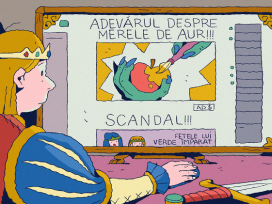

Thirsty for clicks, these portals are eager to launch unverified and often fake news reports. They lack any linguistic culture: in most cases, the writing is unedited, and reports from other languages are often lifted verbatim from Google Translate. Fake news is present in almost every portal that operates in Kosovo, and comes in several forms: manipulation of headlines, manipulation of content, and partially fake news. The sole aim is to attract clicks and satisfy the appetites of the political parties.

There are several types of fake news circulating among the Kosovo online media.

The first type is a headline that promises information, but which is not supported by the content. One example is a report published by Koha.net at 08:21 on 4 July 2017 under the headline ‘AAK Replies to Mustafa’s Invitation to Coalition’, which implied that the political parties were breaking their pre-electoral pacts with the sole aim of forming a government, regardless of their political convictions. However, the item itself did not report anything of the kind, only speculation by an AAK party member, who states, ‘It is not proper for Isa Mustafa, the leader of the LDK, to ask Haradinaj to break his partnership with the PDK in order to work with the LDK–AKR (Aleanca Kosova e Re, or New Kosovo Alliance)–Alternativa coalition.’

The second type is an item based on a question in the headline, generally addressed to a naive public, such as, ‘Do You Know What Gülsaran’s relationship with Özan Is in Everyday Life?’ (Gazeta Express, 17:05, 22 April 2016). Such items are widespread among Kosovo portals, aimed at average readers, who follow the soap operas served up by Kosovo television channels and spend most of their time on the internet.

The third kind of item is one that manipulates both the average and the elite readership, such as: ‘Russia Finances Fake News Against the United States – Who Is Financing It in Kosovo?’ (Gazeta Express, 12:16, 10 June 2017). This headline immediately arouses the reader’s curiosity because, in the present critical state of the media, everybody is looking for the reason for this chaos. The content of the report is entirely different to what the headline promises: a compilation of data published in American media, an article by Peter Singer, the ethics professor and newspaper columnist, some decisions about fake news taken by Angela Merkel’s cabinet, and a bit about Kosovo, which appears to be merely the opinion of the author. The reader, who is inevitably most interested in the part about Kosovo, will be surprised to find that the parts of the article that are about Kosovo bear no relation to the headline. ‘Fake news has become more common in Kosovo too, especially on the threshold of the elections. Some political parties are spreading fake news about their opponents. … In Kosovo, fake news is not covered by the Penal Code because slander and defamation are not considered crimes. These two matters have been decriminalized and are a matter for civil suits against the authors.’

The fourth kind is the presentation of untrue information through a headline, when the source of the content is totally unverifiable, such as: ‘Reuters: George Washington Was of Albanian Origin’ (published by Zëri at 22:32 on 26 July 2016). The same report with the same title was also published also by Infopress (2320 hours, 29 June 2017). Neither of these portals has yet removed this report from their sites, although it is totally untrue. The report has been in circulation among various pseudo-portals since 2011. The daily paper Koha Ditore, following its long-standing tradition of publishing a bogus news item on April Fools’ Day, carried it on 1 April 2011, but accompanied by a note stating ‘April Fo-o-o-l’ at the end. These portals picked up this news item years later and published it as genuine, even referring to the Reuters news agency.

‘The mother of the famous US president was an Albanian with her origins in the Peja area. President George Washington himself is said to have left a letter among his last wishes, asking for America to protect the Albanians at all times and in every way possible. … The Institute of Biochemistry and Genetics based in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, has published the results of the latest genetic research into world leaders, which show that the historic president of the United States George Washington was of Albanian origin.’ (Zëri)

The fifth kind of news gives us its information in its very title. In the following example, both the headline and the content are true, but the time when the events took place does not fit the publication date. At 09:21 on 7 July 2017, the portal arbresh.info (which beneath its mastheadcarries the motto, ‘Only Accurate News’) published a report under the headline ‘Leaving for Holiday, Three Out of Family of Five Die.’ At 09:30, the portal infokusi.com published the same report with the same headline, as did the portal periskopi.com at 10:29. The first portal gave all the information in the headline, in order to gain clicks rather than to act according to journalistic principles. The Albanian or Albanian-speaking viewer or reader will be shocked by the headline, and click on it more readily than if the headline had not included the number of dead. This report would not so far be worth mentioning in our study, because there are such cases in every portal every day, except that the reader, continuing to the body of the report, will discover that this incident in fact occurred in 2014. This not only violates every rule of journalism, but also trifles with the feelings of the relatives of the deceased. No institution has taken action against the portals that published this report, and none of the portals has deleted it.

At this fraught political time, when none of the pre-electoral pacts is able to muster sufficient deputies to form a government, the portals are chock-full of fake news, accompanied by denials from the people and organisations affected by it. However, there is no institution in Kosovo able to investigate such cases or convict the perpetrators.

The crisis in Kosovo society has created a state of apathy throughout the country. In order to alter the direction that the media have taken, what is first necessary is a drastic change within the political parties. Political parties should make the country’s future their priority, not their personal interests and their control of ‘free speech’. Meanwhile, the citizens of Kosovo are preoccupied with their own struggle for survival. Isolated from the rest of the world, and jeopardised by their own state, the crisis in the media is the least of their worries. Only a normalisation of the political, institutional, and social situation would enable us to discuss the normalisation of the media. Only when journalists are truly independent, free, and protected by the state will journalism be able to make progress on the path of truth. As long as no law against slander and defamation is enforced in Kosovo and there are no institutions or any other means to filter information, online journalism will continue to make use of every means to gain the clicks that translate into cash revenue.