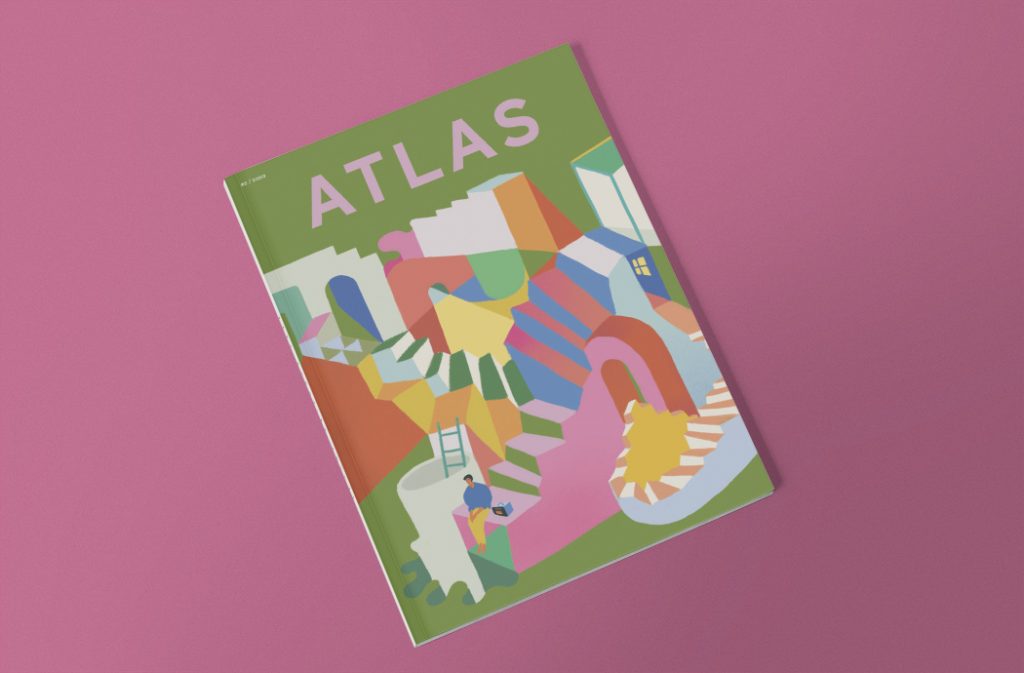

‘Atlas’ argues that art, like humanism, is meta-social and fundamental to knowledge. Also, why Kafka provides insight into the autistic mind; and on the unfathomable world of a Norwegian absurdist.

In Atlas, cognitive scientist Per Aage Brandt invokes the Renaissance as a time when ‘people were not defined by any political, religious and national order’ but belonged to ‘humanity without borders’. In contrast, modern politics are tribal: ‘Collectives claim a shared identity in response to discrimination and, rather than demanding to be treated on the same terms as everyone else, want respect for the characteristic that triggered discrimination.’ Brandt defines the political right as ‘identitarian’ and the left as egalitarian. Art, like humanism, is independent of relationships based on power or wealth; it is ‘meta-social’ and ‘fundamental to the study of meaning – truly, to all thought. Nothing could be more humane than art.’

Autistic Kafka

Jacob Meyer Hald, a young literary scholar who was diagnosed as autistic as a child, sees himself as ‘an impossibility’. ‘Regardless of how hard I struggle, however keenly I try to interpret the signs, something always goes wrong.’ Hald harbours a Hamlet-like wish to melt away and vanish but has found his true literary alter-ego in the ever bewildered K in Kafka’s The Trial – ‘the perfect prism for understanding the autistic mind’. The novel proves that control of the inscrutable world is possible and that ‘autism is a complex way of experiencing the world’.

An absurdist conceit

The latest novel by the Norwegian writer Matias Faldbakken, We Are Five, has been nominated for every serious literary price in Scandinavia. The title refers to an unheard-of addition to a mildly dysfunctional family of four: a ‘dynamic’ lump of clay that acquires a sinister mind of its own after exposure to radiation from a wi-fi router. Faldbakken moved on from the absurdist novel trilogy Scandinavian Misanthropy to write The Hill, an internationally successful ‘chamber piece’ with a wistful theme: the decline of Europe.

In We Are Five, writes Victor Boy Lindholm, he has ‘written himself into an unfathomable world where boundaries between binary concepts dissolve. Limits between nature and culture, living and dead matter, consciousness and unconsciousness, good and evil can no longer be defined.’

More articles from ATLAS in Eurozine; ATLAS’ website

This article is part of the 15/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.

Published 26 August 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Atlas © Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The state unconscious

K24 November–December 2025

Horizons of the Turkish novel; dissident disappointments; communists real and false; the feminine street.

Cosmic Europe

Merkur 12/2025

Leibniz’s Europe; why majority rule is relative; social chromatics off the scale; travels in post-capitalism.