Neganthropology

Czas Kultury 2/2024

The politics and psychology of locality: on reviving local communities as high-tech expands and diversifies; forming networks against entropy; the Tortoise Strategy for caring; and rewriting life scripts.

The workings of western capitalism were almost as unknown in the Eastern Bloc as the everyday realities of ‘real socialism’ were among western Trotskyists. Then, after ’89, eastern Europe disappeared off the political map of the left. Nowhere was this more so than in Britain, writes Owen Hatherley.

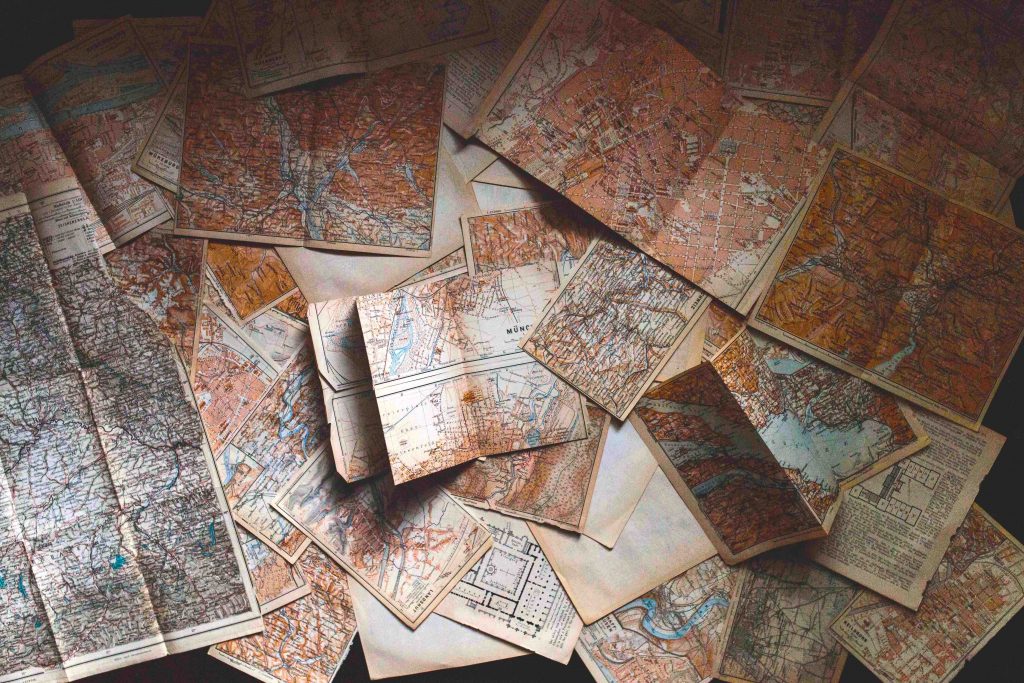

I can remember three particular moments of realising there was a distinct thing called ‘Eastern Europe’ which was different from ‘Western Europe’, and both of them date me as being just about old enough to remember the Soviet Union. One is at Christmas 1989, in my grandmother’s flat on the Isle of Wight, an appropriately plush location to watch, on BBC News, the uprising in Romania and the subsequent televised execution of Nicolae and Elena Ceauşescu, and learn several new words, like ‘dictator’ and ‘firing squad’. Also often said was the word ‘Communism’, but my Trotskyist parents referred to themselves as ‘socialists’ rather than communists, so that wasn’t concerning. What was, was looking in the Children’s Atlas that my mother bought for me in the late 1980s and finding the existence of a very, very large country called the ‘Union of Soviet Socialist Republics’. Being that sort of obnoxiously inquisitive child, I asked her ‘but we’re socialists, aren’t we? Isn’t this our country?’ ‘They’re not socialists. It’s very complicated’, she replied and refused to explain further. The next memory comes a few years later and concerns a Lufthansa map that my dad had brought back from work, where that space had suddenly been filled with over a dozen new countries, all with incredibly evocative names. Belarus! Azerbaijan! Kyrgyzstan!

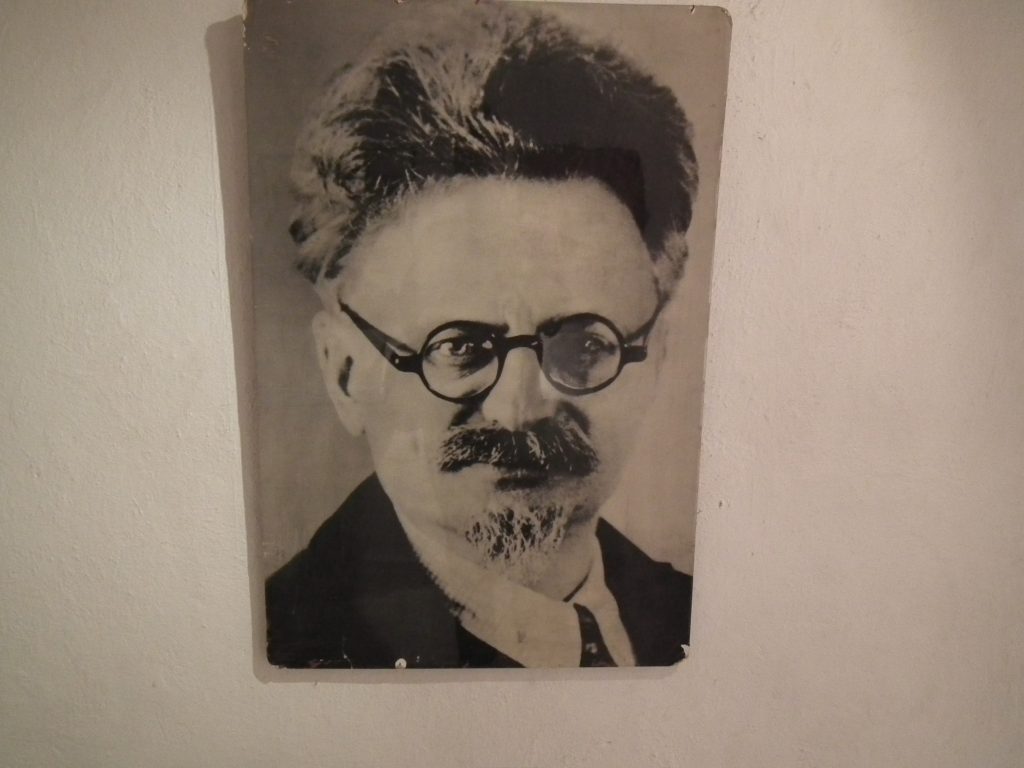

There were pictures of Eastern Europeans everywhere in our house. The odd Lenin here and there (somehow I missed the significance of all the images of Lenin being toppled everywhere), but mostly images of Leon Trotsky, who is, according to a recent clickbait map, still the most famous person to have been born in what is now the independent state of Ukraine, something that is seldom discussed and certainly not celebrated therein. There was a large poster of Trotsky just by the doorway of our terraced house, late in life, wearing glasses and reading The Militant, and looking a little confusingly like Colonel Sanders. Many years later, after I set foot on the hallowed soil of Petrograd for the first time, my mother – who, like everyone in her political ‘tendency’, regarded everything that happened between 1924 and 1991 as ‘Stalinism’, and worthy only of contempt – said that she had always wanted to go there, because, ‘despite everything that happened after, they did it, didn’t they? They made the break.’ If you’ve lived most of your life imagining that one day a cataclysmic event will take place, when the masses will arise, there’s an almost religious awe at the place where it really happened. Trotskyists are the Anglicans of Communism – no wonder then that Britain was one of the few places Trotskyism became, by the 1980s, larger than the official Party.

Image of Trotsky on wall. Photo source: Flickr

What I should now write is a handwringing piece about how we didn’t really understand Eastern Europe, and how this world of ‘Dead Russians’ (dead Ukrainian Jews, in this instance) was a lachrymose cult that bore no relation whatsoever to the actual realities that the people who had to live in the states these people built had to put up with, and which they were then eagerly exchanging for the joys of the capitalism we opposed and fought against at every point. I won’t, I’m afraid. I find it fairly offensively ahistorical to imply that people like my parents, the metalworkers, miners and mass unemployed who made up the bulk of the active members of western left-wing parties were in some way responsible. Perhaps this explains why western Communism is discussed in Eastern and Central Europe as if it was led by Jean-Paul Sartre and boasting its big battalions in the Sorbonne rather than in the car factories.

Of course, I find the cult of Trotsky creepy and a little dishonest about his major role in setting up the repressive apparatus soon turned against him by Stalin. I don’t find most Trotskyist analyses of the Soviet Union and the system it imposed on Central and Eastern Europe particularly useful, but I also find it noteworthy that the ‘Western Left’ that is ritually denounced in accounts of ‘real socialism’ was absolutely right about what would come next. As the 1990s Russian joke went, ‘the Communists lied to us about Communism, but they told the truth about capitalism’. That’s a reminder that the misunderstandings went both ways; knowledge of western capitalism was almost as poor to the east as knowledge of how ‘real socialism’ worked was to the west. I find it extremely telling that a Polish socialist intellectual forcibly exiled in 1968 who took up a post in Leeds would remain a socialist, while a Polish socialist intellectual exiled in 1968 who took up a post in Oxford became a liberal – they had only to look out of the window. For that, it is undeniable that for most of the Western Left this part of Europe just disappeared off the map after 1989, an area without political interest or hope, a sort of dystopia, never discussed or analysed, occasionally lamented.

My own interest in Central and Eastern Europe still centres, I’m afraid, on what happened to it when it ‘made the break’ – partly because it offers dozens of lessons in how not to make the break, but also because of the culture that existed there during that period, and the ways in which the history of these places hints – frequently little more than hints – of what a non-capitalist life, a non-capitalist art, a non-capitalist city might be. My main interest is in what it stopped being thirty years ago. I’m fully aware that this can be profoundly irritating for many people in Central and Eastern Europe, not least among them Central and Eastern European intellectuals, for whom the most important thing is to somehow become ‘normal’, where normality is essentially West Germany on the left and the United States on the right, something that would puzzle people in most of the rest of the world. I’m also fully aware that, especially in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, people calling themselves socialists and communists perpetrated horrors upon these countries to an extent rivalled only by the absolute lowest depths of imperialism and exceeded only by fascism.

Nonetheless, I come to this area as a socialist, and the books I have written about Central and Eastern Europe in the 21st century – the historical Landscapes of Communism and the polemical The Adventures of Owen Hatherley in the Post-Soviet Space and Trans-Europe Express – are shaped by being a socialist interpretation of deeds that were done in the name of socialism.

Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash

But when asked about 1989, I can’t only write as a Western Leftist but also as a citizen of the island at the north-western corner of Europe, which has never shared a border with a ‘socialist’ country. It is hard to express quite what degree of ignorance there is in Britain about Europe in general, but that ignorance becomes especially profound with respect to its East. All the governments in exile in West London haven’t stopped the place being seen almost entirely in Cold War terms. ‘Have you ever been to Poznan?’, one spy asks in the TV adaptation of John Le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, as if Poznan was the worst place in the world, rather than, as it is, a rather pleasant city. There was even, as Agata Pyzik describes at length in Poor But Sexy – Culture Clashes in Europe East and West, a minor cult of evoking ‘Eastern European’ bleakness in the post-punk culture of the late 1970s and early 1980s, sparked by David Bowie’s windswept ‘Warszawa’.

The first mass engagements of British people with ‘Eastern Europe’ – as, of course, we all call it – came with cheap travel to cheap cities, which turned out to be staggeringly beautiful, with their historic townscapes far better preserved than in almost any big cities in Britain. First Prague, Budapest and Krakow (where, in 2013, I once saw a sign in the window of a bar reading ‘No British Tourists Please’), then later, Riga, Vilnius and Tallinn; Lviv was clearly about to be next, had it not been for a war several hundred miles away. This tourism was based on a particularly kitsch notion of beauty, which usually combines architectural heritage, cheap and potent alcohol and the sex industry. Following it, came the mass migration, largely from Poland, Lithuania and Latvia, and to a lesser extent Slovakia, Bulgaria and Romania, elicited by Britain (along with Ireland and Sweden) opening up its labour market to ‘Eastern Europeans’ before most of the European Union.

The racism that came with this really cannot be understated; in public forums, it is often more violent even than the traditional racism aimed towards those ‘Commonwealth’, i.e. until recently colonial, migrants and their descendants. A rightwing paper like the Daily Mail can lament the ‘Windrush generation’ being deported due to the vicious ‘Hostile Environment’ set up by Theresa May when she was home secretary, while running near-constant scare stories on ‘Eastern Europeans’ (Romanians seem to inspire particular terror). Analyses of the Brexit vote have argued that many of the largest votes to leave the European Union have come from smaller towns and cities which previously had low levels of immigration but faced small but significant ‘Eastern European’ settlements after 2004. ‘Where have all these Eastern Europeans come from?’, as the notorious question went from Gillian Duffy, the ‘bigoted woman’ Gordon Brown had an accidental debate with in 2010. Ironically, she was from Rochdale, one of several industrial towns in the north-west to have taken in many stateless Poles and Balts after 1945.

A more recent memory comes from nearly ten years ago – December 2009, to be precise. The second night I spent in Warsaw, a city that I would live in, on and off, from 2010 to 2015, was spent in the company of some representatives of the intelligentsia, in a luxury high-rise flat, all shiny cladding, capacious balconies and polished marble floors, in the inner suburbs. I was, I confess, quite excited to find that ‘the intelligentsia’ still actually existed, something that I wasn’t prepared for by the Western Left idea of this part of the world as being evacuated of everything except money, porn and stucco. I was there because of what was then and is now a friendship, but which for several years became a relationship, with a music and poetry critic who lived in another high-rise, over the road. The flat was owned by the editor of an anti-clerical journal, a man just a few years older than me, who referred to himself as ‘a simple communist’. What I most remember was an argument he had on this subject with a much older liberal intellectual, who will also remain nameless, who had been deeply involved in Solidarity movement in the 1980s, was jailed during Martial Law, and wrote one of the first critiques of it after it came to power. Much vodka was drunk, and then the older liberal told the ‘communist’ that he had been born in Vorkuta; even then I knew there was only one way a Pole would be born in Vorkuta in the 1950s. After this revelation, the two sang revolutionary songs together, in Russian and Polish.

This was the first of what would be many surprises. The intelligentsia still existed; some of them were on the left; and memories of the recent past were still exceptionally vivid. There was also a lot of very good graphic design around. But the next really big surprise was a place that I noticed people just referred to as ‘the Commies’ – Brave New World, a space on the main leisure and tourist street of the city, Nowy Świat, which otherwise had almost entirely become a parade of luxury eateries, apart from one Milk Bar and one drinking bar. Here, the magazine publisher and left intellectual powerhouse Krytyka Polityczna had a ‘space’, where there would be dancing, booze, and heavyweight political and historical debates; what they usually hosted was much the same thing as what I’d seen by accident in that luxury high-rise, a younger socialist arguing with an older liberal. This was extraordinary to me – as if Verso had a ‘space’ on Regent Street, as if Jacobin hosted reading groups in its own cafe-bar on Broadway.

Because of the time I spent here, I would come to write several books either directly about this region or treating it as an integral part of Europe, rather than an appendage. In these, I had several scores to settle. For instance, while the Trotskyist position is essentially that everything was fine in the garden until the death of Lenin at the earliest and the expulsion of Trotsky at the latest, my own idea of the system was much more complicated – confused, I suspect they would say. Becoming more aware of the sheer brutality of the Civil War made the idealisation of the early years absurd. Equally, so was the writing off of everything after their boy got exiled. I was and am in awe at the sheer intensity and sophistication of post-war intellectual life in Poland (and Yugoslavia, and Hungary, and even, in the early sixties and late eighties, the Soviet Union). Moreover, learning about the social contract in these countries made it clear that the differences between the welfare state in the west and ‘developed socialism’ in the east were largely of degree rather than of kind; each side of this contract, in housing, health and education, was closer to each other then than either is close to the current settlement in these countries now. Put simply, the housing systems in Poland or Britain in 1975 shared more similarities to each other than either of them to the housing systems of Poland or Britain in 2019. It was also amusing to realize, while working on urbanism in the former Warsaw Pact, that the preservation (or often, reconstruction) of those historic cityscapes was not a side-effect of ‘the system’, but a deliberate policy.

Ten years later, Eastern and Central Europe are much more discussed in British (and American) intellectual life, but I find most of the frames in which this is done dubious at best, racist at worst. The notion of the New Cold War, that Russia, with its flat taxes, outrageous inequalities and pleasant, hipster-filled urban spaces is some sort of despotic, quasi-socialist wasteland, with Donald Trump of all people enlisted as some sort of Commie Dupe, is utterly absurd. The popular use of fake Cyrillic in the imagery of this ‘resistance’ tells its own story about how little people know or care about the places they’re talking about. Similarly, the notion that there is something especially Eastern European about the ‘illiberal democracies’ that are sweeping the European Union is dubious in the extreme. Viktor Orbán is influential, to be sure, but before him was Silvio Berlusconi (and before Berlusconi, Margaret Thatcher). The far-right is a hugely significant force in France, and is in government or in coalition in Italy, Denmark and Austria as well as in Poland, Hungary and Latvia. To consider nativism, media manipulation and violence as especially ‘Eastern’ is hard to credit if you saw the Leave campaign’s posters or read any newspapers during the EU referendum in Britain in 2016. Even one of the most apparently distinctive features of the shift rightwards in the ‘East’, the quasi-official rehabilitation of native fascists and wartime collaborators, has its correspondents in Italy, France and Belgium.

But what I came to realize most of all was that outside of intellectual life – where there were and are important differences, with Poland still having a state-subsidized intellectual community way beyond that of Britain, albeit within a very circumscribed spectrum of acceptable political debate – there were huge similarities between the Island and the ‘East’ in the 2000s and early 2010s. Endless privatisation, poor quality public space, the dominance of the private car, ignorance about climate change, the destruction of urban planning at any level other than that of conservation, eager junior participation in whatever bombing campaign the United States was insisting on at any given time, and a willingness to inflict economic warfare on feckless southern Europeans (North/South is a much more important political divide in Europe now than East/West) – these policies unite London with Warsaw, Budapest, Bratislava, Bucharest, Riga and Kyiv. We can see the consequences of this evisceration of the public sphere in the murderous fires in nightclubs in Bucharest and high-rises in London. ‘We’ in Britain have more in common with ‘you’ than we do with Sweden or Germany.

Yet the resurgence of an organized socialist left – something different to liberal NGOs or the empty ‘Social Democratic Parties’ of CEE – has bypassed formerly socialist Europe. Opposition to neoliberalism is still conflated with nationalism, a trap that most Central-Eastern European liberals gleefully throw themselves into. The shifts leftwards that have happened in France, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and now Britain, have only one correspondent, in the success of the United Left in Slovenia (for obvious reasons, the rejection of socialism has never run as deep in what was Yugoslavia as it has elsewhere). The notion, amusingly reminiscent of the apologetics for the old system, that what the formerly socialist Europe lacks is ‘real capitalism’ is still popular among the young. If I see hope here, it’s in cross-border efforts in the intellectual world. In the Romanian group Criticatac hosting the trans-national Lefteast portal. In the Bucharest-based journal Kajet, committed to an ‘eastern futurism’ and a look again at utopia. In the work of Russian and Ukrainian leftist poets, artists and writers, opposing the nationalism of both countries, as heard in the unembarassedly socialist voice of Kirill Medvedev. Closer to (my) home, it’s in the fact that some of the most prominent people within the British Labour Party to campaign for freedom of movement have been Poles and Bulgarians. The more ‘normal’ things get, and the bleaker that normality becomes, the more we’ll all come to want something more, wherever we were in 1989.

Published 6 March 2019

Original in English

First published by Eurozine (English version) / Internazionale (Italian version)

© Owen Hatherley / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The politics and psychology of locality: on reviving local communities as high-tech expands and diversifies; forming networks against entropy; the Tortoise Strategy for caring; and rewriting life scripts.

Expectations, standards, and requirements in higher education vary from country to country. In the third episode of the Knowledgeable Youth podcast Ukrainian students embark on the complex subject of tertiary education.