In autumn 2018 Poland celebrated the centenary of its independence. For the occasion, the European Solidarity Centre and private television station, TVN24, organised a discussion with historians, who reflected on the significance of reinstating sovereignty. Timothy Snyder, the author of Bloodlands, spoke about the many dimensions of the concept, and invoked the notion ‘information sovereignty’. In the 1920s, the term described a collective effort in Poland to establish free media, and to develop countermeasures to push back against aggressive disinformation campaigns from Bolshevik Russia. Information warfare was as present and real a danger back then as it is today – except that wireless meant mostly long wave radio broadcast.

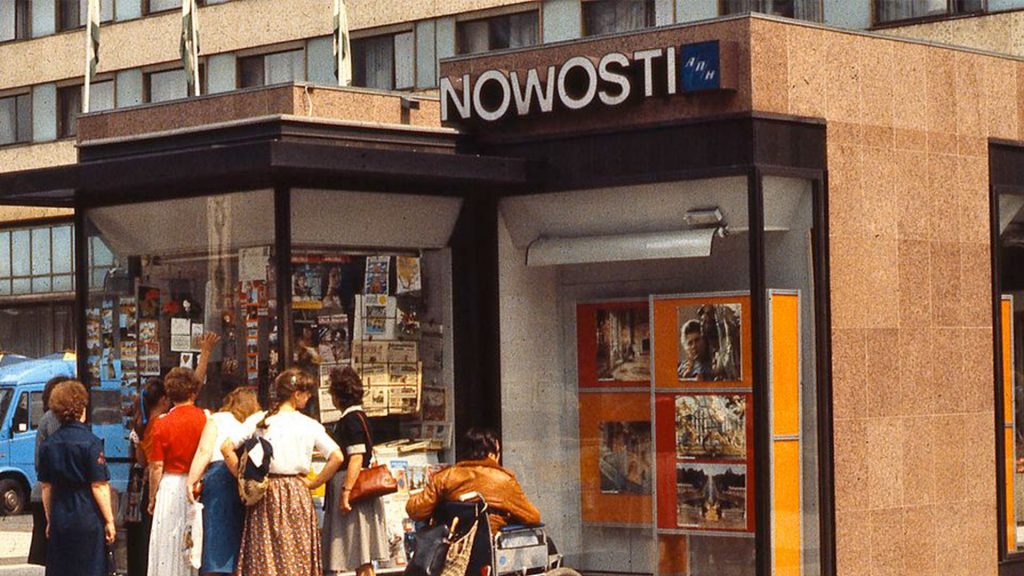

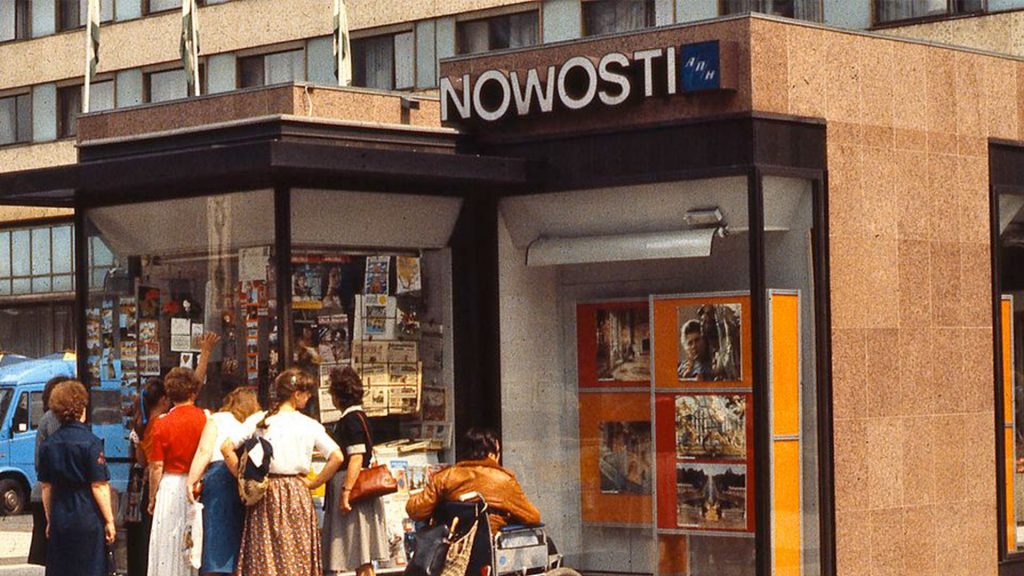

Kiosk run by Soviet Russian international news agency Nowosti in East Berlin in 1984. Photo by George Garrigues from Wikimedia Commons

Idealism and sovereignty

In late October 2018, Poland’s Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, agonising over the disappointing results for PiS in the local elections, picked up the idea of information sovereignty. He referred to German companies’ ownership of media in Poland, indicating that they were partly responsible for influencing electoral results – a common argument used by those who do not perform well in elections. To make his case, he discussed the controversies surrounding the purchase of a German newspaper by a British-American company, suggesting that foreign capital withdrew after large scale public protests.

He was alluding to the 2005 purchase of the left-of-centre Berliner Zeitung by British and American companies. This was indeed the first foreign takeover of a media outlet in post-1945 Germany. But the investors’ decision, four years later, to withdraw from the BZ was based on economic grounds, not because of protests. Since 2019, the newspaper has belonged to the German businessman Holger Friedrich. Ironically, given Morawiecki’s anti-communism, Friedrich was revealed at the end of last year to have been a former Stasi agent.

The trouble with finding a good case for Morawiecki’s version of information sovereignty is perhaps his old-school romantic idealism, which gave rise to the philosophy of nationalism in eighteenth century Germany. Indeed, a striking symmetry exists between the concept of information symmetry and the thought of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, who authored a book entitled The Closed Commercial State. This case for sovereignty, now pursued by many other inward-looking politicians, comes with an ambition to limit all foreign interference and involvement.

The problem with this perspective is that, over time, the circle of intimates shrinks, while the world perpetually pursues more and more interconnectedness. The idealism of men and women in power also stops them from acknowledging how power is used in regimes that idealism despises. Morawiecki could have referred to Viktor Orbán’s government almost complete control of the national media space – another policy blueprint from Budapest that has obviously been studied in Warsaw. But he did not, probably because of rising corruption in Hungary, which is part and parcel with Orbán’s illiberal policies.

Shortly after Morawiecki’s speech, I interviewed Timothy Snyder for Dziennik Gazeta Prawna and Res Publica Nowa and asked him to clarify his position on the idea that he had injected into Polish political discourse. Snyder spoke about challenges to Poland’s and other countries’ sovereignty likely to arise in the future, and about wars that are today fought more in the mind than on actual battlefields. This new theory of warfare, drawn from Carl von Clausewitz and others, has allowed Russia to develop active measures, including modern-style propaganda. Meanwhile, resilient democracies have been able to promote critical thinking and media literacy, mainly thanks to publics that value the written word. As Snyder acknowledged, in the digital age, the greatest democratic challenge is to retain a bottom-up approach to information sovereignty: a framework in which free, independent and pluralistic journalism can flourish.

The importance of local journalism

One of the most serious debates about potential democratic backsliding today is the collapse of local journalism. Local communities, so fundamental to democracy, are most exposed to misinformation and deception. In 2015, the New York Times’s The Agency report provided compelling evidence of how local America is under attack from Russian disinformation networks. Disinformation operations were deliberately carried out where the public sphere was the weakest. While The Economist and the New York Times thrive with millions of online subscribers, many smaller outlets have been collapsing and professionals are abandoning the trade. Digitalization and the financial crisis are often cited as the reasons for the decline in media and journalism, but this gives way to a fatalist notion of the survival of the fittest.

Fortunately, in Central Europe, there is some hope. Dennik N in Slovakia is one example of a success story. The digital daily was set up by journalists who resented the idea of a big corporate owner. It quickly grew and became the country’s top news subscription service, breaking even in just under five years. Similar cases have followed across the region, with a digital transformation allowing some to emerge.

People are hungry for news and analysis on how events of the day can be explained. Even in Hungary, where the government has taken control of a bulk of outlets, there is a degree of experimentation. In 2018, the weekly HVG – one of the few outlets still independent of government control – started an online subscription service featuring long-form quality stories. It is now paving the way for quality, independent media in the country. Perhaps more innovation with digital models would improve the situation in Hungary. Current tools allow media in Hungary to be used as government mouthpieces, rather than serving plurality and carrying out independent inquiry. Journalists lose their jobs, while the newspapers they once worked for replicate stories, headlines and even images, thereby ridiculing the notion of citizen’s right to information.

Trends

This takes place in parallel with the expansion of the Kremlin’s narrative through more and more information channels, thus threatening Hungary’s information sovereignty. In 2019, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) resumed its services in Hungarian. Established in 1949 by the US Agency for Global Media to provide objective information to societies subjected to mass propaganda by various communist regimes, RFE/RL has recently also re-opened Romanian and Bulgarian branches – all of them as online platforms, rather than radio waves.

It may sound like a paradox, but multinational stakeholders in the region guaranteed more information sovereignty than national governments do now. This is not to say that the answer is complete privatisation. The changes in the media landscape that we see in central Europe may soon become a trend across the rest of continental Europe.

Levels of trust among central Europeans in established (paid) media brands are very low; instead, there is a preference towards alternative (free) sources. This is striking when compared to public attitudes towards the media in Germany. Trust in journalism in central Europe is undermined by politicians, who have an even lower level of public trust. Miloš Zeman, the president of the Czech Republic, and Robert Fico, the former prime minister of Slovakia, competed to discredit the profession of journalism. The former showed a fake Kalashnikov, tagged ‘for the press’, while the latter called journalists ‘prostitutes’, not long before one was murdered (Ján Kuciak). It is hard to see how quality-driven subscription models (based on trust) can develop quickly when they are fighting against a very strong current.

Yet the press is just one side of the coin in the battle for information sovereignty. In Slovakia, cultural archetypes and cultural diplomacy led by Russia may be one of the reasons for the country’s inability to abandon its post-imperial dependency on Moscow. According to Aliaksei Kazharski, a researcher at Comenius University in Bratislava, ‘pro-Kremlin narratives and their promoters are also sometimes legitimised by established cultural and educational institutions that are anchored in a reputable tradition.’ For instance, the Slovak Matica (Matica Slovenská) – one of the oldest Slovak cultural institutions – ‘has close ties with pro-Russian radicals in Slovakia as well as its controversial interpretations of the Holocaust aroused public suspicion … Similarly, the Slovak Union of Anti-Fascist Fighters, established in 1969 as a veteran organisation, has published a magazine which, as Slovak journalists put it, became a tool of “Russian propaganda”. The magazine did indeed actively republish dubious material, containing anti-western conspiracy theories and Russian-inspired disinformation tropes.’

State of mind

In contemporary democracies, there is an understandable reluctance to use the term sovereignty. Its poisonous legacy draws from pre-democratic sources of power and the mystical authority derived from the powerful and the divine. No wonder that Hobbes puts a monster – the Leviathan – as the archetype of the liberal sovereign power that emerges from the contractual concessions of individual freedom.

It is also not surprising that contemporary authoritarian regimes are so attracted to the concept of sovereignty. By claiming the term, autocrats like Vladimir Putin suppress voices of dissent that call for democratic accountability and limited government. Russia, too large territorially to act as a functional political space, is more like a state of mind. In order to control the physical space, Moscow believes it needs to control the mindset – and the information that makes it up.

By declaring sovereignty over a geographical territory, the economy and even the internet, Putin has tried to claim the high ground in the struggle for the hearts and minds of Russian citizens. In reality, he has taken the fight back to the West. Unable to defend itself from the democratic narrative, Russia went on the offensive. Today, Russia may infest the democratic mindset if the threat it poses is not properly recognised or addressed.

Democratic sovereignty in general, and information sovereignty in particular, must be the opposite of how Russia understands them. By advocating democratic information sovereignty, Central Europeans must fight for the ability to defend themselves against domestic and foreign propaganda. It needs to be acknowledged that governments that knowingly restrict citizens’ access to information, a human right, directly help hostile countries. Even with its contemporary autocracies, central Europe will never be as effective in exercising such control as the Russians or Chinese. By trying to imitate them, central European government make their citizens even more susceptible to the influence of foreign powers.

Chinese-style information sovereignty is incompatible with the democratic legacy and will never succeed in Hungary, Poland or any other European country. But since the Chinese and Russian information sovereignty models are more offensive, they need to be taken into account. The task for our governments is to educate the public so that it will be able to resist authoritarian influences, especially in the information space.

The still young central European democracies have been reluctant to address the idea of information sovereignty. Yet the idea is infectious and spreads regardless. Ultimately, only though a collective effort will it be possible to take back control of the media.