Part 1: Bullet holes as ornament

The attackers meticulously planned what to destroy and what not to destroy. Their aim was to psychologically incapacitate the inhabitants of the city. The mental targets were those structures that the people identified themselves and their culture with. Museums, libraries and squares. All gone. When the facades of a city are destroyed its face lays beyond recognition but when its heritage sites and public places are targeted, it deprives the city of its legibility, disconnecting the inhabitants from their surroundings. Still to this day, the injured city is under attack.

Architecture came to play a major role during the last war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, especially in the city of Mostar. After the war the recovery of Mostar became a slow, complex process, partly due to the fact that the city was divided into two parts. Each belonging exclusively to a specific ethnic group. Currently it is impossible to walk through Mostar without being confronted with the war that massacred the city between 1992 and 1995. Mostar has become a dishonest city. What we see is an abundance of fragmented, self-proclaimed and self-imposed commemorations. Mostar was once a clear repository of symbols and memories, now the city has become hazy, almost opaque. Will the citizens of Mostar ever be able to read their city?

Perhaps this is an irrelevant question. Just as the citizens have changed, the past is being retold and emphasized in competing ways through symbolic architectural interventions. The people of this city, just as all over the Balkans, continue to look to the past because it now determines their future to such a great extent. But how can the mental recovery from war proceed when the physical reconstruction of the city is obscured to such a great extent by politics? How can people deal with their history when they are constantly confronted with destroyed buildings and with new religious political symbols of division in public space?

As history is no longer visible in the city’s architecture and its public spaces, communication between city dwellers and Mostar itself has ceased to exist. Due to destroyed buildings and added symbols it is impossible for the inhabitants to shrug off the war’s legacy, to deal with it and to forgive. Since the new generation of citizens who did not experience the war directly are not able to meet each other and engage in a dialogue prejudices will live on.

What else stays behind after the death of a city? The rubble, the survivors and many memories. Memories not only located within Mostar but dispersed among the many countries that the inhabitants fled to. In his book Van de Zomer naar de Werkelijkheid (“From summer to reality”, 1997) Dutch writer and journalist Chris Keulemans refers to Dubravka Ugresic, a Croatian author who explains the possible modes of survival during and after the Bosnia-Herzegovina war:

Somebody who has to live through a war can choose from three modes of survival: adaption, inner exile or fleeing. All three are a kind of tour of the underworld, which has to be made in order to reconquer the right to a new life. All three demand from a survivor the discarding of his old life, of the habits and preferences from which it was made, the characteristics by which his environment could recognize him.

The decline and destruction of the conventional industries, the unemployment, decay and empty spaces of the city centre coupled with an unsafe environment drove the young and educated away from the city. The absences created by the people who fled combined with the addition of refugees from the surrounding rural areas created a new social structure for Mostar.

The effects of the destruction during the war can be divided into two categories: physical and mental. The physical ones are the most visible – roofs, frames, windows and parts of facades have been blown away by grenades and bullets have destroyed buildings, creating vacant dwellings alongside the streets littered with grenade shell holes. Neglected for a long time, their interiors are overgrown and their walls often covered in graffiti. As climatological influences slowly erode the ruins, the scars from the wars become yet more visible, more natural even.

This results in an image that is not only horrifying but fascinating too. These interiors become part of the public space. Those who dare can enter the buildings and might even appreciate their new characteristics. As the vulnerable materials have not endured the war, the buildings reveal their construction, the basic shapes of their architecture. The thousands of scars from grenade shells and bullet holes have become ornaments. Even so, these buildings should not be considered romantic ruins. Their destruction is not the result of neglect or abandonment but of sudden and deliberate annihilation. A fascination with destruction is not new to the world of art and architecture. Sometimes we appreciate this through myths and religious histories such as the story of Sodom and Gomorrah (present in both the Bible and the Koran), which act as a great source of inspiration. The German artist Gerhard Richter has been amply inspired in his work by events during World War II and the American architect and artist Lebbeus Woods took as the impulse for his work such events as the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in San Francisco. Artists who live in countries marked by war find themselves in between the horror and fascination that grim images evoke. In “From summer to reality”, Chris Keulemans cites two poems by Bosnian poet Semezdin Mehmedinovic, who writes about the fascinating images of destruction in Sarajevo:

FIRES

On his way home after photographing the Vijecnica, which was going up in flames, Kemo Hadzic got injured by a grenade shell. It is hard not to think mystically during a war. My first thought was: his injury is a warning. Kemo says he didn’t feel any pain as long as he was in shock.

In order to feel pain one has to be aware of pain, whilst being in shock – while it lasts – is a form of staying on the other side. It is a dive into the world of the practices of art as well: because what was this photographer exactly doing while he encircled the burning library, looking for the ideal viewpoint and light conditions with the water of the Miljacka captured in his wide angle lens; what else was this than the fiery longing of the artist to extract the ferocious beauty from this horrible spectacle of death, to approach it from the other side.

The urge of the artist to venture into the unknown is perilous but precisely in this venture lies the power of art. Would it be possible to say that the grenade shells were a punishment for that heretic step? Perhaps that is not more than just an esoteric thought brought up by the panic of the war, the same way a boy – who Kemo, in shock, followed to the hospital and only noticed again after surgery because of the doctor, while he provided him with some cool air by waving a folded newspaper – the same way I recognize a creature in that boy that does not belong to this reality any more. Because of the boy’s angel-like gesture.

GLASS

I walk towards the window and look at the broken glass panel of the Jugobanka. I could keep on standing there for hours. A blue facade of glass. On the floor above the windows behind which I am watching, a professor in aesthetics enters his balcony: he puts on his glasses and combs his beard with his fingers. I can see his image mirrored in the blue facade of the Jugobanka, in the broken glass panels that turn the scene into a living cubist paining on a sunny day.

For me, a destroyed building tells a story, shows a transformation and most of all, leaves a lot to one’s imagination. Suddenly a building is shrouded in mystery. This environment of destruction is not just fascinating but also fosters the daily remembrance of war. Inhabitants will not be able to put these memories to rest as long as the destroyed buildings are still there. How could one commence his or her own mental reconstruction when the physical environment is destroyed?

Part II: (Re)constructions: Separate and equal

Besides physical changes that took place during the war, Mostar had to deal with the transformation that came about after it. People slowly began to rebuild: not only buildings but also the government of the city. In March 1994, the Washington Agreement put an end to the war between the Bosnian army and the Croatian Republic Herceg- Bosnia. The agreement took the divided situation of Mostar seriously and the European Union obtained a mandate to govern the city for a period of two years. The European Union Administration of Mostar (EUAM) aimed to maintain peace, facilitate the return of refugees and restore essential institutions to the city.

Two years later, the mandate of the EUAM ended and the Office of the High Representative (OHR) was founded in order to develop new strategies for the unification of the city. An Interim Statute was established for the city as a temporary solution for its self-governance. The Statute allowed for the separation of the city into Croatian and a Muslim parts. Seven large autonomous districts were created: three in the west with a Croatian majority, three in the east with a Muslim majority, and a small commonly governed Central Zone.

Mostar’s city centre contained three of these seven divided districts: the Croatian-governed southwest district, the Muslim governed old city and, in between the Croatian and Muslim districts, the Central Zone. The Interim Statute also appointed a central city government with a mayor, a deputy mayor and a city council. This citywide government – which was also supposed to control the Central Zone – did not have a lot of authority due to the segregated power of the districts.

Each district had its own urban planning authority. Each started simultaneously, but separately and without consulting one another, to rebuild the city. As it was the only politically shared space, the EUAM hoped that the Central Zone would be an area where interaction and discussion between the two ethnicities could take place. They hoped that soon the Interim Statute would be replaced by a permanent statute and that the Central Zone could be the physical starting point for a reunited city. This Zone occupied an important part of the city, resulting in fierce discussions about its borders. It was a matter of dispute as to whether specific symbols or economically vital places should be included in this area.

The two most important elements that were not part of the Central Zone were the Liska Street cemetery, which contained both Muslim and Croatian graves, and the water supply. Both were assigned to the authority of the Croatian districts. However, the Gymnasium and the bus and train station were part of the Central Zone. Due to the resistance of the Croatian controlled districts, the Central Zone turned out to be much smaller than the EUAM and the Muslim controlled districts had initially hoped. This was seen as impairing the chances of future unification.

Between 1997 and 2003, several attempts were made to unite the provision of public education and medical infrastructure services – without any success. In 2003, a commission was founded, dedicated to reforming the city and handling its problematic divisions. The six districts were done away with as governing units and replaced by a single city government. However, the interests of the districts survived this move, as the districts became constituencies. In 2011 the constitutional court declared the then current Statute as unconstitutional because the number of representatives of the constituencies did not correlate with the numbers of voters in each constituency. The city has been waiting for a new statute ever since.

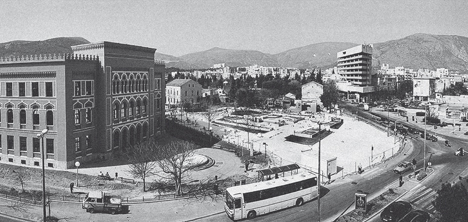

The aforementioned developments resulted in a very complex political climate, hindering the rebuilding process. Many post-war reconstruction projects have reflected these difficulties. The reconstruction of deliberately destroyed public and religious buildings raised questions and controversies. Debates concerning different identities and conflicting tendencies toward separation and unification could be perceived in the architecture and public spaces. Many religious symbols and monuments have been added to the public space. Streets have received new, often nationalistic, names and ethnically and politically coloured institutions have been given prominent places in the city. But the Central Zone, the public space that is most shared in Mostar, is subject to the biggest controversies regarding the (re)construction of buildings. One example is the Gymnasium, heavily bombed during the war. Built during the Austro-Hungarian era, the building is considered to have housed one of the best high schools of Yugoslavia before the war. Because it is located in the Central Zone, it was intended to be a shared space for the inhabitants of both Croatian and Muslim districts. No discussion was dedicated to the way it would be rebuilt: it needed to look exactly like it did before the war.

The Gymnasium, destroyed. Photo: Arna Mackic.

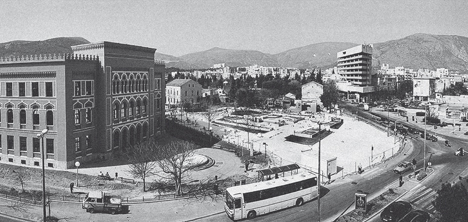

The reconstructed Gymnasium. Photo: Arna Mackic.

In 2000, the Croatian district reconstructed the first floor of the building alone and reopened it as the Brother Dominik Mandic Grammar School. Naming the school after a Franciscan friar made it clear that the school was intended exclusively for Catholic Croats. The OHR responded by deciding that once the entire school building was reconstructed, both Croatian- and Muslim-run schools should be housed there. Under the slogan “separate but equal schools” the two institutions would share the same roof and function apart from each other: each with their own board, curriculum, students and entrances.

In 2003, as the opening of the new Old Bridge and the political unification of Mostar came closer, the OHR and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) proposed merging the boards of the two schools as well as the mathematics and science curricula. From that point onwards the two schools in the Gymnasium shared the same name, board and physical building. Yet the students were still being taught separately, exceptions being the teaching of the mathematics and science curricula. In 2006 the United World College (UWC) of Mostar moved in to the third floor.

This high school aims to contribute to the reconstruction of post-war societies by way of education. It has students of many different ethnic groups from former Yugoslavia, as well as many countries in southern, eastern and western Europe, the Middle East, the USA and many crisis countries like Israel and Lebanon. It is remarkable that a single structure can hold such a vast quantity of contradiction, of divisions and unities and still stand, still support its own weight. Despite the single city government Mostar remains culturally and socially separated to a large extent. The Central Zone, which for a decade was the physical border between the two ethnicities, has now become a buffer zone. A kind of no man’s land that cannot be ignored because it is located at the centre, the heart of the city. Twenty-two years after the war and eleven years after the political reunification of the city, it somehow remains a neglected area to be avoided by all. There is little there: neither shared spaces nor many private ones. In the absence of regulations and decisions that might have enabled construction projects for the area to proceed, the fate of Mostar’s Central Zone remains in limbo.

Part III: The Jump

The city has existed for centuries, longer than the generations, longer than the languages, the very powers and religions that took shape and found refuge here. This history should be visible in the architecture and the public space of the city. It should not be imposed upon the citizens by restoring the city to the state in which it was found prior to the war or by reconstructing buildings in their original style. Rather, the reconstruction of the city should be based on the cultural history of the city. Especially in a city where the war has mutated so much.

In Mostar everything is ethnically and politically charged: every building, every monument, every street name. In a society where the past and memory itself have become so vague, we have to look for a new language, a clean language that nobody will politically, religiously or ethnically identify themselves with. A language that does not ignore or deny the past but engages with it and puts it in a new perspective without imposing truth. It is a language that glances upon the future, like the monuments commemorating the victims of World War II in former Yugoslavia built between 1950 and 1980. This new language could be compared to the way the Dutch designer Jurgen Bey in an interview for the debate series “In de Toekomstige Tijd: Utopisch denken in het onderwijs” describes the beauty of the language of art, that exists within the reader:

“It is an open language that does not seal things but a language that, if you listen to it, provides potential and because of that can work as an accelerator. The beauty of the language of art is that it is much closer to literature. Everybody who reads a book knows that the language only exists with him or her. Everything you know comes forward; anything you do not know doesn’t exist.”

The biggest design challenge for Mostar lies – apart from the obvious necessary architectural tasks like the (re)building or renovating of houses, hospitals, schools, parks, et cetera – in forming a new open architectural language. This language could not be applied to everything or acquire every possible function. As regards the rebuilding of destroyed buildings, the opportunities lie, for the most part, in buildings that did not have any significant political, religious or ethnic meaning before the war. Everything that was viewed as “meaningless” was left untouched during the war. Those sites and structures that were saved consequently continue to exist as “open” places. Neutral and unburdened by the past. Places that can mould the potential of a new future. The Central Zone – the part of the city that should be an entirely “open” place – consists of a couple of these places, such as the Glass Bank building. For the construction of new buildings the opportunities lie in constructing something that is not burdened by religion, politics or ethnicity but that instead is closer to the creativity and individualism of the arts. As these buildings would employ a new architectural language their function should be mostly public and aimed at affording encounters between people. This new architectural language doesn’t have to get rid of symbols. The Serbian architect Bogdan Bogdanovic used symbols for the monuments he designed throughout Yugoslavia that transcended ethnicity and religion in order to avoid making any political or ideological statements. Instead, he found his inspiration in archeological shapes and kept diving deeper into the richness of archetypical images. He tried to reach the primal shapes of the imagination. We can learn a lot from Bogdan Bogdanovic efforts in order to decide the new functions of the neutral places. What if we would focus on functions that have to do with ancient traditions that go beyond any specific religion or ethnicity? To get there it’s important to recognize the cultural, historical and spatial qualities of Mostar – the ones that do not refer to ethnicity and religion. Currently this language cannot be found in architecture and urban planning. In theatre and music, however, there are a couple of examples that employ a new open language liberated from politics or ethnicity. The Mostarki Teater Mladih, the Mostar Youth Theatre, educates young people in practical drama and production and is open to anyone regardless of their ethnicity or religion. Experimentation, openness, development and bridging differences are both a way of working and a life philosophy for the members of the theatre group.

The Mostarian band Zoster – which named itself after the Herpes zoster virus and rose to fame thanks to the bad condition of the immune system of the society they reside in – tries to insert tolerance, peace, development and love to the music scene of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This band, which was founded in 2000, has experimented with many musical styles and has become even more abstract in their language and expressions over the years. Mario Knezovic, the band’s front man and singer, told me that he does not want to impose a message upon his audience. When listening to their music I can find many references that point towards the political, social and economic situation of Bosnia- Herzegovina and Mostar.

However, the stance of Zoster in their lyrics is precisely to remain neutral. With their music they convey things without saying them. They keep things open in order for listeners to appropriate them. When I ask Knezovic if his lyrics would be different had he grown up in another city, he hesitates but eventually sticks to his point: it is not about the message, it is about opening up, offering neutrality and a possibility to hold on to it. This seems the best possible strategy for Mostar: to not force people to be together but to offer them choices in thought and in living. It probably would be the best approach to apply to the urban planning of Mostar as well. An area similar to the former neutral zone cannot function when it is very pronounced and specific but will only work when it is neutral, when it allows people to make it their own by employing an open language. That’s why it is essential to implement an architectural intervention that is grounded on precisely this stance: not taking any stance.

Mostar currently finds itself in an exceptional condition. It will never be the way it is right now, not ever again. Exactly how a city like Mostar will restore itself is unclear. What we can be sure of is that the city will never keep on being itself. It will rather mutate into a totally different society. The inhabitants of the city have a big responsibility, they share something unique (their images of destruction) and will contribute to the building of this new society. It is to be hoped that religion and ethnicity will one day not control the role of the schools, fire departments, cellular networks, hospitals, football teams and bus stations. That these institutions will be reduced by half: one of each for both parts of the city. Shared and equal.

Finally, I will share a jump into the water. One of the most important traditions of Mostar is diving off of the Old Bridge, which has occurred since 1567. It used to be a ritual where young men dived off the bridge to prove their manliness and impress young women. Later it became a tradition that was carried on from one generation of Mostar men to the next. Boys learnt step by step how to dive and ultimately become skilled enough to jump off the Old Bridge. A diving contest is held every year, where the most famous international high board divers take the plunge.

“A tradition that comes from the origin, the very structure of the city.” Photo: Arna Mackic.

In order to form a new operational architectural language in the “neutral” zone, I propose a building that includes a diving school where citizens can learn, step by step, to dive from great heights with the descent from the new Old Bridge as the final step. By designing such a place, an urban activity is made available to all the inhabitants of the city, regardless of their nationality, religion, gender, age or sexual orientation. It is not just diving off the Old Bridge but also diving itself that is an age-old tradition. Diving is something atavistic. It is pre-religious. Historians question whether jumpers found on pre-Christian paintings could actually swim. it may be that diving even predates swimming.

In Mostar it is a tradition that comes from the origin, the very structure of the city. Without the existence of the Old Bridge the tradition would never have been there. Even after the war when the Old Bridge was demolished and before there was a support bridge, there was a springboard from which people could dive into the river. The jump is a form of survival for the inhabitants of Mostar, it is something they can hold on to, because it forms the foundation of being a Mostarac or Mostarka, not just a member of some district. The Dutch architecture historian Thomas A.P. van Leeuwen writes in The Springboard in the Pond (1998) that springboards were introduced into the domain of swimming to enrich “the feeling of weightlessness” and as “a springboard for the swimmers’ eternal play with death”. The sensation of weightlessness is the feeling of “eternity”, something without limits, infinite, oceanic. Furthermore, swimming is an important and meaningful part of diving. Swimming has to be taught or else one is bound to drown. Everything one undertakes to overcome this condition could be explained as the continuous battle against what one does best by nature: sink.

Swimming teaches us to keep our heads above water. The three-second long jump towards the water gives a feeling of weightlessness and freedom where one becomes detached from everything around him, including the tangled public space of Mostar. Perhaps the divers of Mostar can create their own communal immortal moment this way.