I remember exactly what I was doing on the morning of 21 August 1968, when Russian tanks invaded Czechoslovakia. I was eleven years old, spending the summer in a cottage with my parents. From the hilltop I watched the column of tanks in the valley below, and I saw my father cry for the first time.

I remember exactly what I was doing on 17 November 1989, when police beat up students in Prague and the communist regime started to crumble. I was at a meeting of banned writers, and when we heard on Radio Free Europe what had happened we got into our cars and drove home to Bratislava, knowing that history had been made.

But what was I doing on 1 August 1975, when the leaders of 35 countries signed the Helsinki Final Act in the Finnish capital? When reconstructing my memories, I figured out that I must have spent the day hiking in the Slovak mountains with my brother.

The signing of Helsinki Final Act was an event that had a direct impact on the collapse of the Soviet empire, but I only have a vague recollection of the headlines in the communist press. The newspaper celebrated the document as a great victory for Soviet diplomacy, which was enough for me to ignore what had happened up there in Finland.

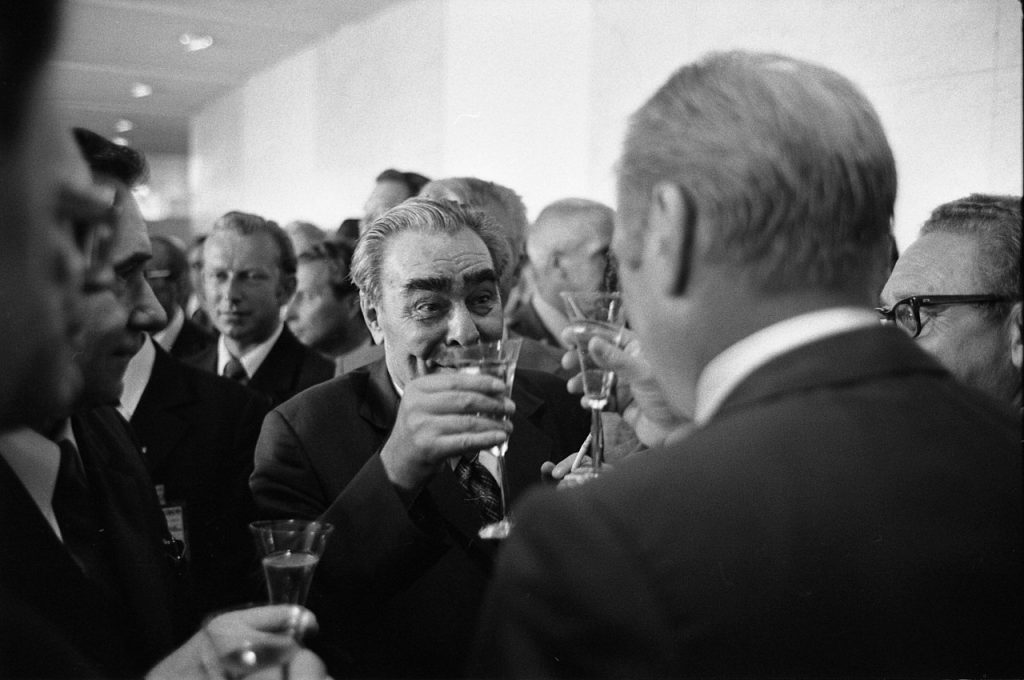

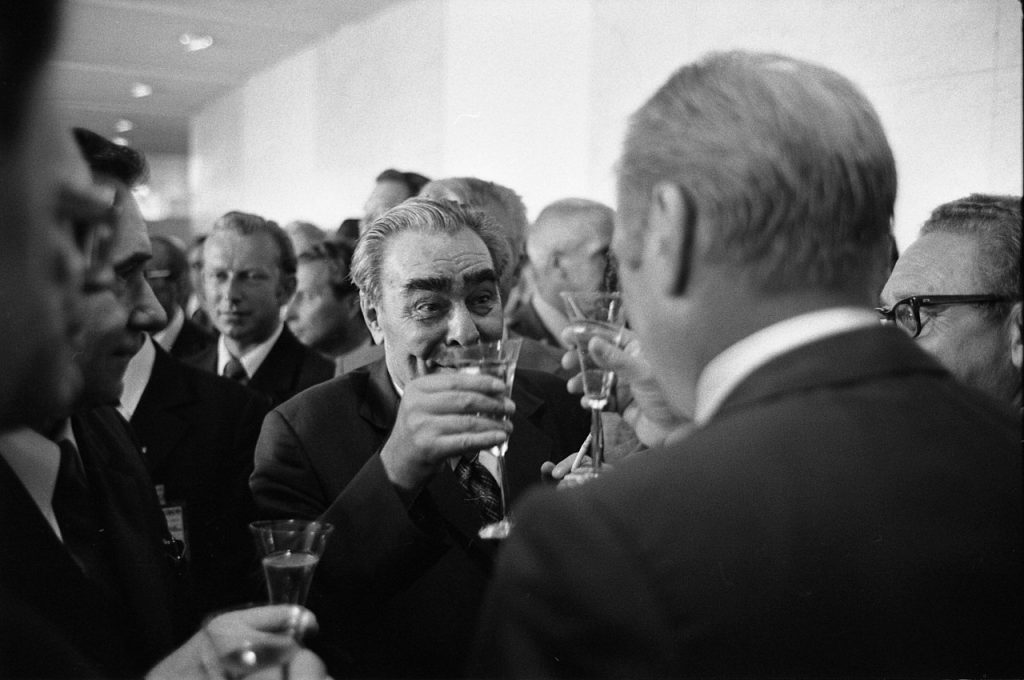

Leonid Brezhnev and Gerald Ford toast after the signing of the Helsinki Final Act on 1 August 1975. Image: Gerald R. Ford Library (Ann Arbor, MI) / source: Wikimedia Commons

Fifty years after the Helsinki Final Act, how can we get back to a rule-based world order? From 15 to 18 May 2025, the Helsinki Debate on Europe will address some of the most pressing issues on the European agenda. Ahead of the event, Eurozine publishes articles by speakers and panellists.

The full programme of the Helsinki event is available on the website of Debates on Europe.

But I do remember a seemingly insignificant event a year and a half later, on 31 December 1976, one that was directly related to the Helsinki Final Act. A stranger rang the doorbell of our apartment. When I opened, he handed me an envelope and told me to give it to my father. Then he disappeared.

That stranger had taken a risk, since our family was under constant surveillance. He had probably assumed that the secret police would be off duty on New Year’s Eve. The envelope contained a few typed pages of text, entitled ‘Declaration of Charter 77’ (‘Prohlášení Charty 77’). The signatories were friends of my father: the philosopher Jan Patočka (who died three months later, after eight hours of secret police interrogation), the playwright Václav Havel and the former politician Jiří Hájek.

My father, Milan Šimečka – a philosopher and dissident living in Bratislava, the Slovak part of Czechoslovakia far from Prague – read the text and angrily remarked that when writing it his Czech friends had forgotten about the Slovaks and now all they wanted from them, from him, was a signature.

I’ve read that my father was a signatory of Charter 77 so often that I’ve given up trying to correct the mistake. And anyway, it hardly matters, since my father’s biography and attitudes were identical to theirs – including imprisonment. The fact is, however, that my father did not sign Charter 77. He was too upset by the self-centredness of his friends in Prague.

But why didn’t I sign it? I had no reason to be offended. I was 20 years old and the communists had banned me from studying at university. I was earning my living as a labourer and had nothing to lose. I had become a dissident because, according to the communists, I was the bearer of original sin. I had every reason to sign Charter 77.

I agreed with every sentence, except for the one that proposed ‘a constructive dialogue with the political and state authorities’. Dialogue? No way! Of course, it might have been just a tactical manoeuvre, but I wanted nothing to do with the communists. Even during police interrogations I remained staunchly silent, because any answer I gave would already have been a dialogue.

So I didn’t sign. But this did not prevent me from admiring the genius of Charter 77. Among the key authors of the text were Pavel Kohout and Ludvík Vaculík, both former communists who knew the regime from within. They understood that its weakness was a morbid desire for western recognition. The communist regime saw the Helsinki Final Act as its victory because the West accepted the Soviet empire – including Czechoslovakia – as a partner. The fact that Czechoslovakia had simultaneously agreed to respect human rights was considered to be an insignificant concession that citizens did not need to be informed about. (Although they could read it for themselves when the Helsinki Accords were published in the Collection of Laws on 13 October 1976.)

Charter 77 was a carefully aimed blow, because it accused the regime of ignoring the commitment it had formally made in Helsinki. When the manifesto was published by western newspapers in January 1977, the regime – rightly – considered it to be a direct attack on its legitimacy.

Even the signatories had not expected it to have the effect it did. An unprecedented wave of repression ensued, together with a massive propaganda campaign to defend the regime’s legitimacy. In public meetings throughout the country, hundreds of thousands of people voted for a resolution condemning Charter 77, although the vast majority of them had not read it. After all, any re-publication had been prohibited.

The regime forced thousands of artists from all walks of life to swear allegiance by signing the resolution. Czechoslovakia’s most famous actors and singers were broadcast on live television speaking out against Charter 77. It was an orgy of conformity and cowardice. This ‘anti-charter’ became a kind of board of shame after 1989, and several artists later publicly apologized for putting their names to it.

At the time, however, the Helsinki Final Act seemed to be a victory for the communist regimes. The brutal repression of dissidents in Czechoslovakia confirmed this. I was not alone in considering the West’s efforts towards a détente with the Soviet empire as a betrayal of the millions of people oppressed by communism. I was convinced that the dialogue between the democratic West and the dictatorships of the East was perfidious, nothing else.

Turning point

Fifteen years later, it turned out that I was wrong – and that the communist dictatorships were wrong too. Trade with the West, which they had hoped would strengthen their economies, could not remedy their backwardness. Western guarantees of non-interference could not stop the Soviet empire’s internal disintegration.

It had also become obvious that the commitment to peace supposedly contained in the agreement was nothing but an illusion. I lived the entire 1980s in an atmosphere of hysterical fear. On a daily basis, communist propaganda scared the life out of us with warnings about America using a ‘neutron bomb’ and starting ‘star wars’.

The West German peace activists who organized mass marches against the stationing of American Pershing missiles in Europe were affected by the same hysteria. But to my astonishment, they did not protest against the Russian nuclear warheads that were aimed in their direction. As Francois Mitterand laconically remarked in a speech to the German Bundestag: ‘Missiles are in the East, pacifists are in the West.’ To this day we do not know exactly how many of these missiles were installed in Czechoslovakia.

It seemed to me that the Helsinki Final Act had become just a scrap of paper, yet another international document that no one took seriously. But as Henry Kissinger later said, ‘turning points often pass unrecognized by contemporaries’.

The ‘turning point’ appeared at the time like a formal addition through which the West could relieve its guilty conscience for abandoning eastern Europe to Stalin. But it was more than that. This was the famous ‘third basket’ of the Helsinki agreement, which contained all the formulations on human rights and freedoms.

What the communist states assumed was mere decoration added to an international treaty that de facto recognized the immutability of the Yalta agreement on the division of Europe, instead became a hammer that gradually smashed the concrete structure of the Soviet empire.

However, at that time and place, in Czechoslovakia in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Helsinki Final Act appeared to have ushered in more of the same, just worse. Václav Havel spent four years in prison; my father more than a year. The persecution of dissidents became even crueller, the secret police changed tactics and, in addition to bureaucratic repression, started to beat up ‘Chartists’, harassing them and driving them into exile.

In Poland, the communists ruthlessly suppressed the Solidarity movement, relying on the fact that the Helsinki Accords recognized the right of states to do whatever they wanted at home, without any interference from outside. The Czechoslovak communists also often used this argument. Any western criticism of the persecution of dissidents was indignantly dismissed as ‘interference in the internal affairs’ of the state.

So I had no reason to think that anything would change. Instead, I was convinced that I had to defend my freedom on my own, without the help of the West, and that this would be a lifelong task. I never dreamt that the communist regime could fall in my lifetime.

But something started to change. Throughout the 1970s, I didn’t meet a single westerner – of course, no one in my family had a passport until 1989, so we couldn’t travel. After 1980, however, strangers would from time-to-time ring on our doorbell, introducing themselves as journalists, or as a professor from Oxford who had come to give a philosophy lecture to the few dissidents for whom the intellectual rewards outweighed the risk of being taken away by the police for interrogation.

It felt like being the indigenous object of an anthropological field study. People from another civilization began to come to our communist wilderness, and I was amazed to find out that they were interested in us. I had no illusions that visits from the West would change anything. But the discovery that there were people living behind the Iron Curtain who thought about freedom just like we did was of enormous importance to us, and to me personally. If it hadn’t been for what had happened in Helsinki, they would never have been able to visit Czechoslovakia at all.

Sometime in the second half of the 1980s, the chairman of the Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, Karel Schwarzenberg, came to visit Bratislava. So my father invited him to dinner. When I asked Schwarzenberg how, as someone considered an enemy of the Czechoslovak communist state, he had managed to cross the border, he just smiled and said: ‘They had to let me through.’

That was when I finally understood the full significance of the Helsinki Final Act.

From soft power to no power

At that time, initiatives and associations with names such as the Helsinki Committee or the Movement for Civil Freedom were multiplying in Czechoslovakia. There were soon so many that the regime could no longer suppress them all. All were different versions of Charter 77. And all referred to the Helsinki Final Act.

These organizations were founded on human rights, whose legitimacy the communists had formally recognized in 1975. They all stressed dialogue, despite the fact the authorities continued to reject it. I therefore had no reason to change my own position. I greatly admired the imagination and perseverance of the Chartists, but I was still not interested in negotiating with a violent regime.

The sclerotic communist systems in eastern Europe might eventually have collapsed of their own accord, without the Helsinki Final Act and its third basket, and perhaps even without the dissidents. But such a collapse would have lacked an essential element: the ethos of human rights, which was what the dissidents embodied and which was formed on the basis of the Helsinki Accords.

Today, it is often assumed that human rights led to the fall of communism, as if this were a natural or even necessary development. But it did not have to be that way at all (as the Chinese example proved all too clearly). Human rights became an effective political tool for change only through the imagination and perseverance of the dissidents in the East and the activists in the West. Without these people, the Helsinki Final Act would have been an empty document.

The idea of human rights helped the states of Central Europe to manage the transition to democracy with remarkable speed. The process was accompanied and supported by a strong dissident narrative, cultivated above all by Václav Havel, who became the president of Czechoslovakia in December 1989. In the post-communist states where dissidents did not come to power, for example former Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria, the transition took much longer. In some cases, like Russia, it failed altogether.

But while the soft power of the Helsinki Final Act undoubtedly accelerated the collapse of the communist empire, it had no hard power. If a state actively chose to ignore it, it was powerless. It was powerless when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in late 1979; it was powerless against the Serbian nationalism that killed in Sarajevo, Srebrenica and Kosovo in the 1990s. And it is powerless against Russian aggression in Ukraine today.

This is not a reproach of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which is built on the moral principles of human rights and freedoms established in Helsinki. But its authority evaporates the moment a state openly mocks those principles.

Russia is a prime example. In the first half of the 1990s, Boris Yeltsin pushed the West to focus on cooperation within the OSCE instead of expanding NATO to include the central and eastern European states. (Although Yeltsin also publicly acknowledged in Warsaw in 1993 that it was the Helsinki Final Act that gave states the right ‘to choose their alliances’.) Afraid that the West would join in with the Russian game, at this point I began to perceive the OSCE as a risk. Without any hard power, the organization was no guarantee against a renewed attempt by Russia to dominate the newborn and fragile state in which I lived. At that time, Slovakia was ruled by Vladimir Mečiar, an authoritarian populist whom Yeltsin called his friend.

In other words, the OSCE, which during communism I had been grateful to for standing up for dissidents, suddenly became the bogeyman of a compromise between Russia and the West. I didn’t want to rely on the OSCE to protect my freedom, because I knew that it couldn’t. The wars in Yugoslavia were tragic proof of that. I was worried that the West would back down and that the OSCE would serve as an excuse for doing so. It was only when it became clear that Slovakia would become a member of NATO and the EU that my fears were abated.

Since then, I’ve lost interest in the OSCE. I am not the only one. How many times in the last two decades has the OSCE done anything that has caught the attention of European media? Again, this is not a reproach. The Helsinki Final Act was signed at a time when the West and the East were trying to avoid war. Most states were then still headed by politicians who had experienced World War II first hand.

Fifty years on, the world looks very different. Russia has launched a war against Ukraine and is ignoring international treaties and agreements. The Budapest Memorandum signed by Russia in 1994 (along with the USA, Britain and Ukraine), which was supposed to guarantee Ukraine’s sovereignty in return for giving up its nuclear weapons, has become nothing more than a scrap of paper, as have the Minsk ‘agreements’.

In a world where international treaties are no longer valid, the OSCE is an organization without authority. In countries where human rights are being massively violated, dissidents may still feel that the OSCE is interested in their fate. That is better than nothing. But the soft power of the Helsinki Final Act has been exhausted, precisely because contemporary authoritarians don’t even pretend that they recognize its principles.

In 1975, an international treaty was signed that opened up space for dissidents in eastern Europe who, thanks to their imagination, were able to use it effectively. The moment in history in which we live today also requires the imagination of those who care about democracy. But the essence of imagination lies in coming up with something new. Old formulas no longer work; the past cannot be repeated.

Perhaps, at this very moment, another ‘turning point’ is occurring. A turning point that we, the ‘contemporaries’, do not yet fully understand. It would be nice if it was happening under the auspices of the OSCE. But I suspect that this is not the case.