It is cheering to look out over a series pastorum, as the Church puts it – a congregation of shepherds. Although here, the congregation is made up of editors – a series redactorum. Realising just how much of Sweden’s cultural life depends on the holders of these posts is quite a revelation.

I have decided to approach this talk from a subjective point of view – that is, based on my own reading of Ord&Bild over very many years.

I began reading Ord&Bild in the 1950s in the public library in Kristianstad, my home town. At the time, Bonniers Litterära Magasin was the flagship among magazines; required reading for anyone with serious literary aspirations. Back then, the mere suggestion that the BLM was to fold a few decades later, first once and then again, would have seemed insane. To write for it was incredibly prestigious. I succeeded in getting a slightly odd article about Lars Ahlin into one of the 1962 issues. I was 22. This feat deserved a big celebration and I remember asking my then girlfriend out to a restaurant. Those were the days when you paid about 20 kronor for a substantial meal for two, complete with pudding, aquavit, beer, coffee, and a brandy to follow.

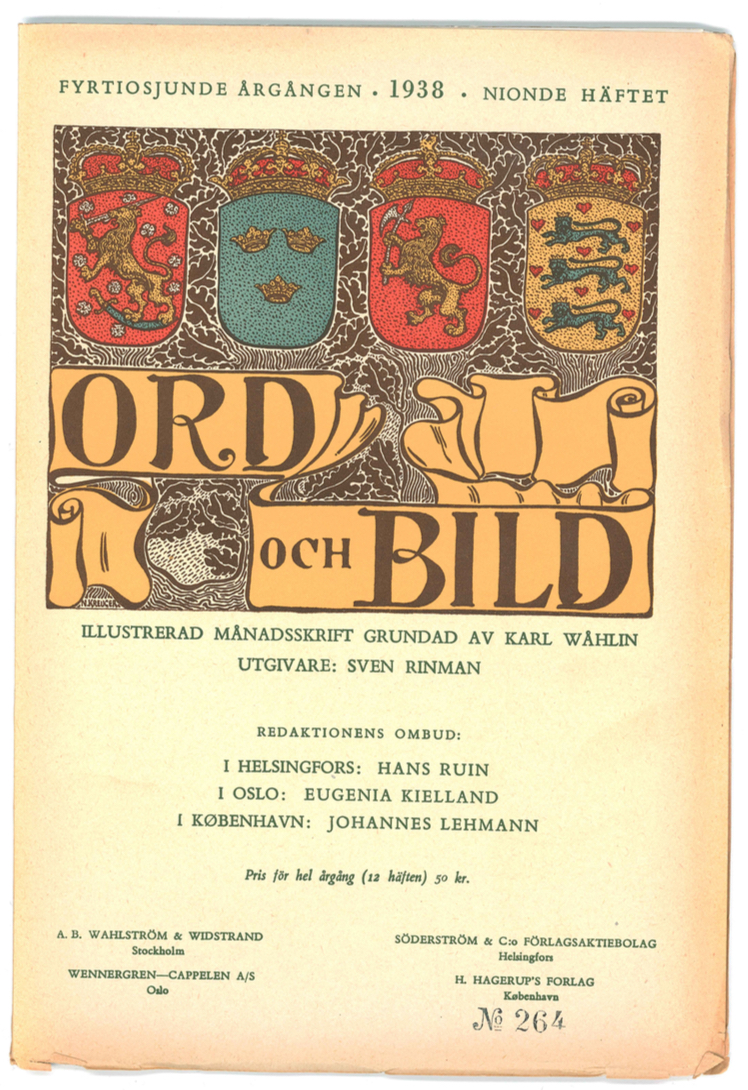

Ord&Bild 1938

In the 1950s, Ragnar Oldberg edited Perspektiv, a magazine about culture in the provinces. Before moving to Lund, I lived in the countryside myself and, at the time, people would go on about how dull these rustic backwaters were. This piece of conventional wisdom infuriated Ragnar Oldberg, who insisted that the ‘real Sweden’ was to be found away from its big cities. That is surely a proposition everyone can agree with?

In the 50s, many of us read Horisont, an excellent, lively Finnish magazine. Ord&Bild was another important source of reading matter but seemed imbued with something of a drawing room atmosphere. Between 1951 and 1957, the editor was Lennart Josephson, an aesthete who had also published a collection of short stories that I remember reading; next came Björn Julén (1958–61), a poet, literary scholar and book reviewer. In a way, the magazine’s upper-class aura seemed typical of the 50s. When, later on, it was taken by two men both called Lars, it felt as if doors to a wider world had suddenly been flung open. Lars Bäckström arrived first (1962–70) but I believe that Lars Bjurman (1963–72), in particular, left his imprint on the magazine for years to come. I’m probably right in saying that Bjurman lasted longer than any other editor apart from the grand old man and founder, Karl Wåhlin (1892–1937).

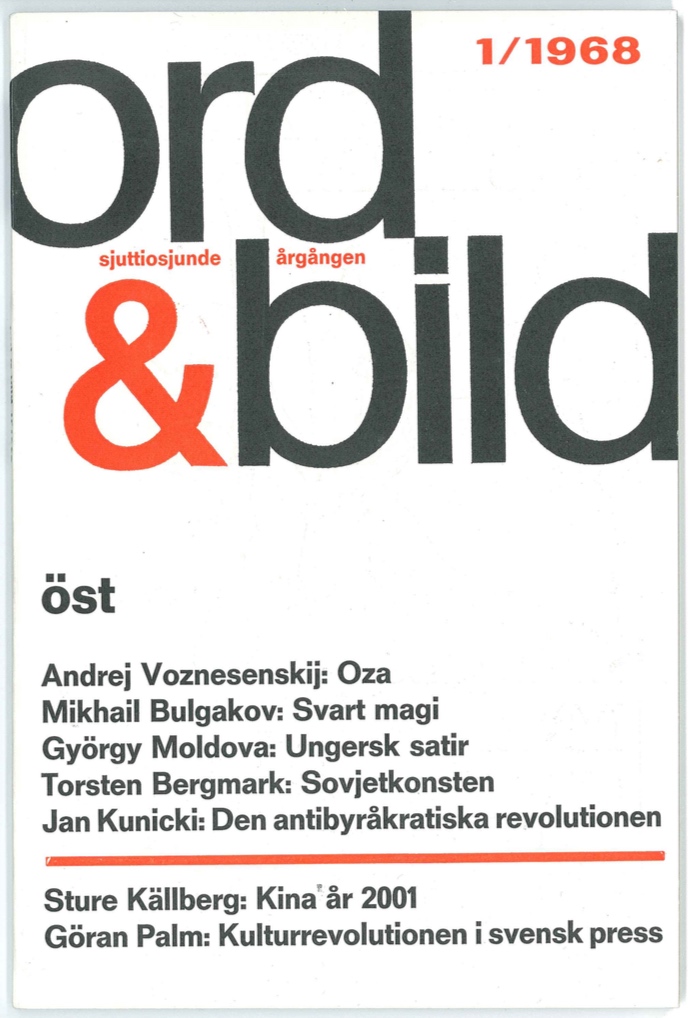

Lars Bjurman was a polymath, immensely well-educated and an excellent translator with many contacts in Europe and elsewhere. I met both editors face-to-face, Bjurman more often than Bäckström. I found Bäckström memorable because most of his conversation was about ‘the new plain poetry’. At the time, I was one of the ‘aristocratic modernists’ as Göran Palm called us, so it followed that I didn’t care at all for ‘new plain poetry’. I recall arguing with Lars Bäckström about it in a radio programme. Be that as it may; Bjurman was the man with the contacts and the ceaseless energy. His was a wholehearted take on the editorship: one discovered so many things in his magazine. It is fair to say that Ord&Bild was often a few years ahead of its time.

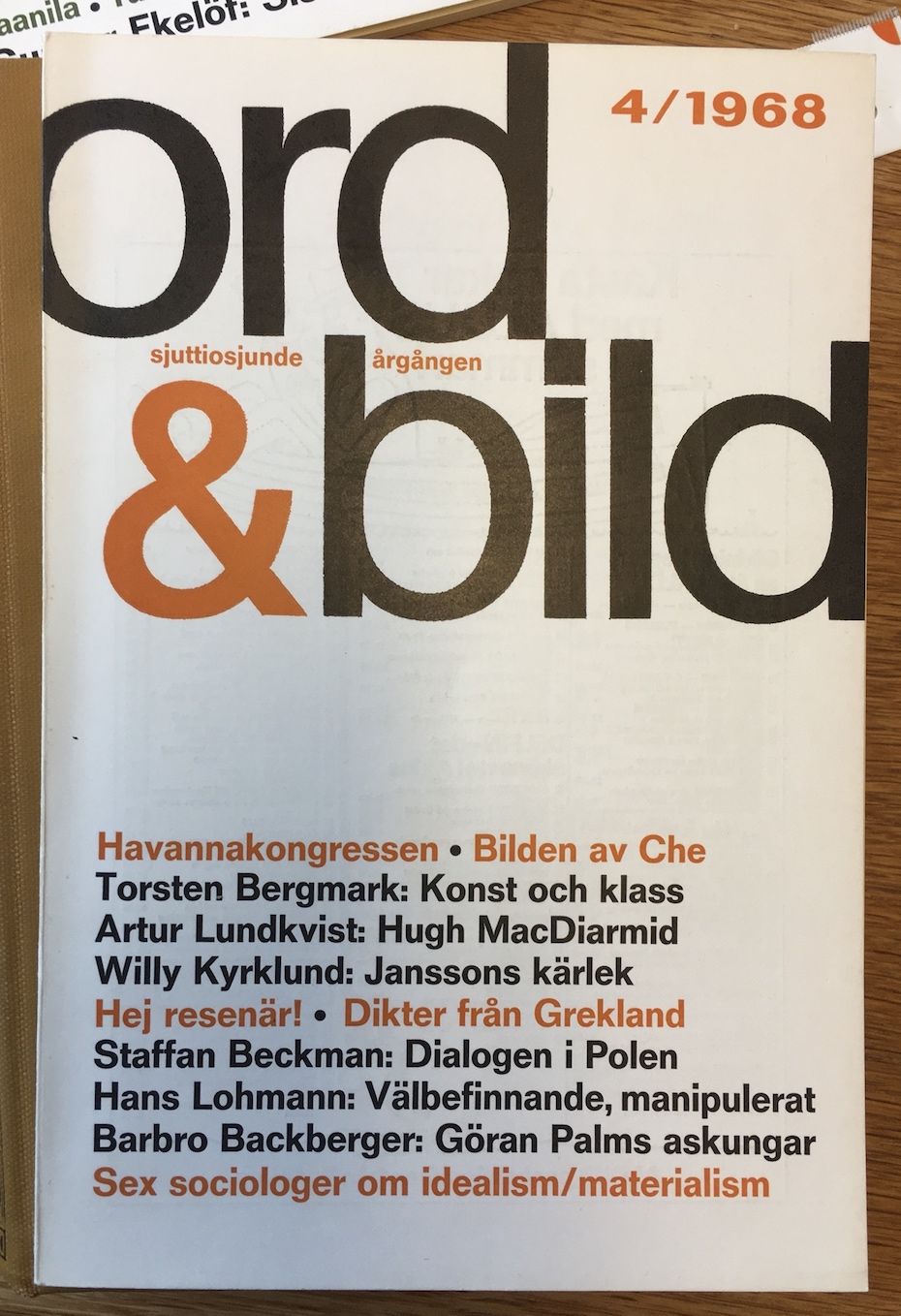

I remember being struck by how often I would suddenly find in its pages things to read about eastern Europe that were quite different from the usual fare in Swedish publications. Lars Bjurman knew about the early stages of intellectual opposition, not only to Stalinism but also to what followed; for instance, the events that were taking place in Poland. And it was not all about Leszek Kołakowski and Adam Schaff and their Marx-focused discussions but also about the great poets introduced by Bjurman, Zbigniew Herbert and others. Bjurman had his own perspective on what happened in the world. The process known as decolonization was taking place at the time. Nowadays, we are of course aware that colonialism survived, but in new forms.

Ord&Bild 1/1968

Ord&Bild 4/1968

Ord&Bild 6/1968

This was a great time. It is interesting to read with hindsight what was published in Ord&Bild. I’m ashamed to admit that I never realised then, although I do now, that it was Lars Bäckström – that is, the other Lars – who in 1969 translated parts of Valerie Solana’s SCUM Manifesto (issue 2/1969). Honestly, I think this is quite remarkable. The 1960s was a brilliant period. Eventually, the wave of all that we connect with ‘the ’60s’ broke over us and brought about a revolution. With it came big changes in literature, art and music, and then the political stuff we associate with 1968 but which had begun a few years earlier.

That wave continued to flow powerfully during the 1970s. Soon, the period of many editors dawned. Themed issues became a special feature of Ord&Bild. There were magazines in other countries that did this kind of thing but I believe Ord&Bild might well have set the pace in Sweden. I remember in particular an issue focused on Swedish healthcare (issue 6/1975). At the time, people didn’t tend to write about healthcare and it made a huge impression. I wrote something for it myself, with a quite radical approach to the subject while viewing it from a historical perspective. The funny thing is that, long afterwards and as recently as last year – many decades later in other words – when turning up at large, annual conferences for physicians I would meet people who in their youth had read precisely that piece of mine. They and I have gone grey, but they still remember the article in Ord&Bild and associate it with me. Many themed O&B issues left strong impressions; most of all, I think, the selection of articles about schools that Rune Romhed put together in the 2000s (issue 3–4/2006). It had several print-runs and was reissued many times over the years.

But I mustn’t get ahead of myself. The 1970s and ’80s were, as I have already said, the time of the many editors – nineteen of them altogether. It brings to mind the early days of O&B, when Karl Wåhlin lasted for 45 years. There could be four or five of them at a time, and they might stay in charge for one or two or three years. But, at the same time, looking down the list, most of the names are recognisable from an endless number of other contexts – they’re such a highly qualified lot. My guess is that the 1950s editors I mentioned must have felt that they were working against a headwind. It was the period when Sweden built its ‘home for the people’, created a comprehensive education system and, via state agencies, made huge investments in the sciences, above all the social sciences. In such a society, who cared to spend serious money on literature and art? Later on, in the ’60s, the two ‘Lars’ set sail in a tailwind. Or, perhaps, they were well on their way already and were carried by the wind that of course continued to blow during most of the 70s.

In the 1980s, a new school of thought suddenly caught on: we know it as neoliberalism but it is actually so much more. It started in Chicago. The great father-figure was Friedrich Hayek, and then came Milton Friedman and Gary S. Becker and others who were eventually awarded the Economics Prize set up in the memory of Alfred Nobel. The French economist Thomas Piketty is probably the person who has most explicitly drawn attention to what he regards as the conservative Anglo-American revolution. It is, in my opinion, a very good definition. What counts as a revolution? We might well think of the French revolution and the revolution of 1848, and perhaps the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 but, at the same time, we also speak of the industrial revolution. The first person to use that phrase was Louis Auguste Blanqui, a French revolutionary, and the second was Friedrich Engels. A revolution entails enormous changes.

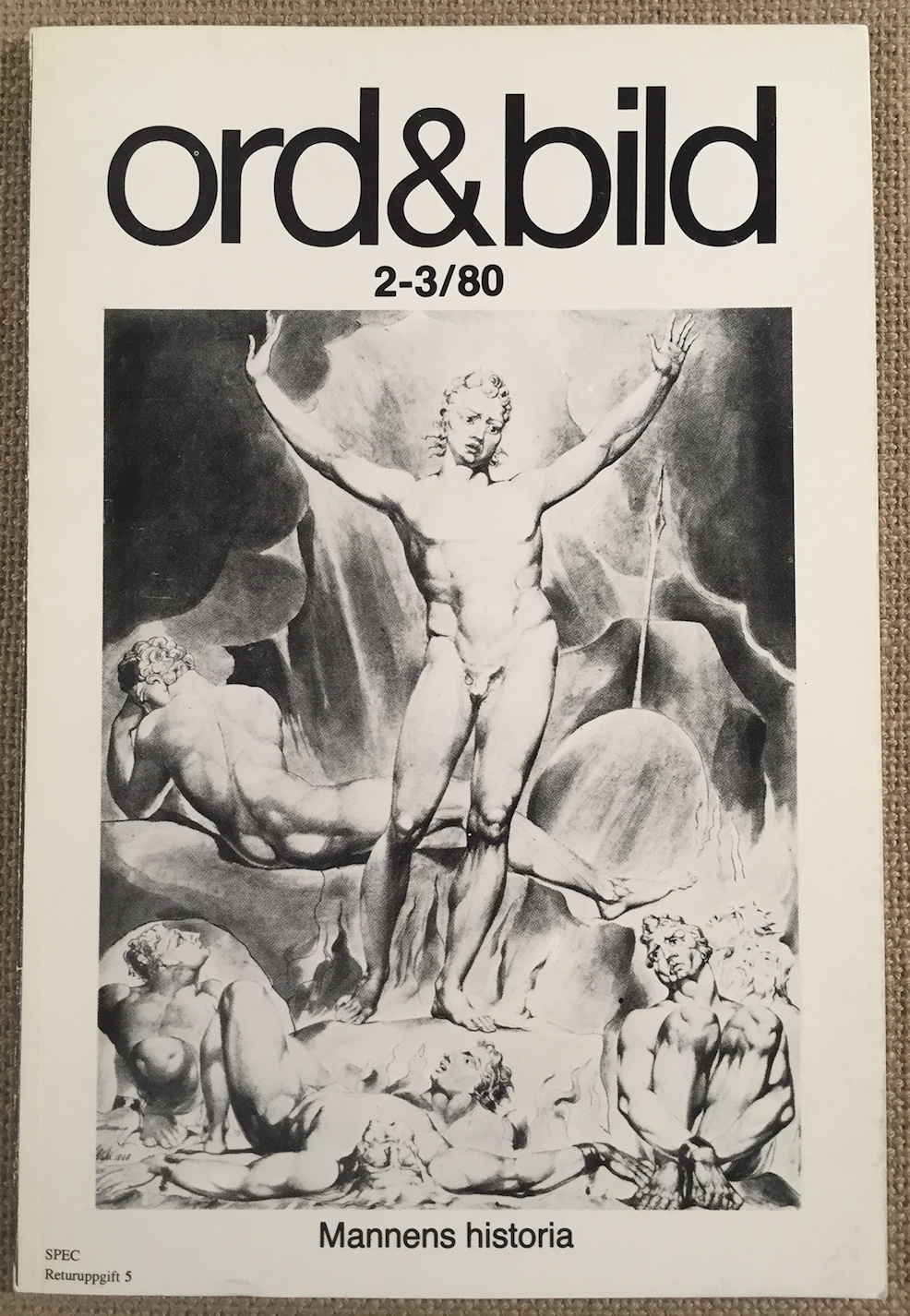

Ord&Bild 2–3/1980

The Anglo-American revolution wasn’t fought on any barricades but it led to a thoroughgoing change – a tremendous number of things that were around in the 1970s are hardly recognisable now. The deregulated international economy followed from this revolution, as did extremely hostile policies towards trade unions, enforced especially in the UK and the USA, where people also embraced the notion that only the individual mattered and that society meant nothing. Margaret Thatcher was the great champion of this line of thought and declared that there is no society, only individuals.

It is a world view that also regards the worth of work in sectors such as philosophy, history, art and music as defined by the amount of money this or that activity pulls in – which is precious little, mostly. I can say with some certainty that this ideological change is the third I have experienced during my long life. The first was after the end of the Second World War, when that had been ruined by Nazism and fascism was to be reconstructed. The ideologies themselves would be wiped off the face of the earth for good, and new societies built in a more sensible way than before. Then came the ’60s. This may not have been as absolute a change but, still, it was a tremendously big one. We use ‘1968’ to symbolise it, but the change had actually got under way in the early years of the ’60s and lasted for a long period, well into the ’70s. The third great change was that conservative Anglo-American revolution. Obviously, Ord&Bild was working with the wind blowing against it but, at times, a headwind can feel stimulating.

In the 125th anniversary issue (issue 3–4/2017), there is a reference to the long essay by Anu Mai Köll (issue 5/1980), in which she asks where ‘university Marxism’ has gone; it vanished in 1980. I don’t think people in universities really noticed it – it was a gradual change – but she had registered it with the precision of a seismograph. Perhaps it is easier to pick up such changes in Stockholm than in Gothenburg. I’m not sure. Arne Ruth discussed the new conservatism in a long essay (issue 2–3/1980), wondering whether it really was new or just the old form in disguise. Also, there was an essay about conservatism by Jürgen Habermas (2–3/1981). Generally speaking, quite a few great names were featured very early in Ord&Bild: Edward Said, Marshall Berman, and many more.

Ord&Bild 2–3/1981

Towards the end of the ’80s, at some point or other, Ord&Bild moved from Stockholm to Gothenburg. I don’t know exactly which year it was, but the editor was Mikael Löfgren and the chairman D Hansson. It is rather strange but noteworthy that Gothenburg is now the home of three of the unquestionably most significant magazines in Sweden – arguably the most significant ones: Ord&Bild, Glänta and Arche. And there are quite a few others as well. In a way, the magazines are counterweights to the depletion of the daily papers in Gothenburg, a process that has been going on for years. For a long while, the city had only one newspaper – the Göteborgs-Posten. Many newspapers have disappeared; that one dominated during all the years I have lived in Gothenburg. Still, it is fair to say that when it comes to journals and magazines, Gothenburg is the most important place in Sweden.

A new tradition began with the editors who took over in Gothenburg. The list begins with a sequence of individual names: Mikael Löfgren, Johan Öberg and David Karlsson, who are present in the audience today. Carl Henrik Fredriksson does not seem to be here. But Annika Ruth Persson has turned up, as has Cecilia Verdinelli and Martin Engberg. This sequence covers many years but then, not all that long ago, we observed the new approach: two editors at a time. At first, the pair was Patricia Lorenzoni and Ann Ighe. Now we have Ann Ighe and Marit Kapla. I think it’s quite amusing to see how the change-over works out at different points in time but, all the same, it is a well-established Gothenburg tradition. When you are as old as I am, the realisation that thirty years have passed since the magazine moved to Gothenburg is quite stunning. One might say that thirty years add up to a very long time but as for me … I think it feels like yesterday and that Ord & Bild celebrated its 100th birthday only quite recently – that is, twenty-five years ago. It was a fascinating centenary. The exceedingly elderly but completely lucid Per Nyström gave a great speech. I remember that he had had an amputation and was wheelchair-bound but he gave a brilliant presentation. The subject was poverty in Sweden during the Second World War.

Ord&Bild 5/1994

It is always hard to characterize events that are close in time. I feel reasonably confident about dealing with the ’50s and ’60s but much less so about the period between the end of the ’80s and the present day.

What is so attractive about Ord&Bild is that it has at all times been finely balanced between society and art in its widest sense, including literature, music and film and so on. As a whole, the magazine serves as a mirror held up to the present day but, more than this, it has also taken contemporary society to task for many years. It actually came up close and fought it, always forward-looking and often critical. The other aspect of the magazine is just as essential: to discuss literature and images, as its name suggests. As a matter of fact, I have spoken far too little about that aspect, perhaps because the changes that take place in the art world are more subtle markers of the contemporary scene than the articles that go out and grab hold of whatever is out there in the here and now – or the recent past, or the imminent future. Wave motion in the arts – or whatever is the right phrase – can surely be just as dramatic but tend to cause less of a splash.

However, aesthetic changes have been clearly reflected in the magazine. From Julén’s 50s via Bäckström’s own plain style to concrete art, then to the engaged art of the ’70s and on to postmodernism, they have all left their mark. Now, the topics are drawn from the complexity of the present. Everything, from the ‘documentarism’ about which Martin Engberg edited an excellent special issue, to art forms so liberated they seem to herald their own extinction (issue 5/2010).

The 125th anniversary issue of Ord&Bild contains one example of how art can look now, presented in a poetic chapter taken from Hanna Nordenhök’s thesis and entitled ‘Delta. Utler Topography’. It’s a fascinating ethnographic poem about a meeting between the German writer and poet Anja Utler and Hanna Nordenhök. It also allows us to watch a Faculty of Arts thesis in the state of becoming. I feel it has much of what characterises poetry today. Think, for instance, of Gunnar D. Hansson’s latest collection of poems – and not only his latest one. In his work, too, you can also find the same transcendence of boundaries; an approach that suddenly lets something new in. It makes illusions fall apart. I am also reading Göran Sonnevi’s latest collection of poems and found that he also has space for such boundlessness.

Just now, we are living through another ideological turn-around, which can be summarized in a list of names, all with unpleasant connotations: Trump, Putin, Erdoğan, Duterte and Åkesson. The deregulated economy is galloping ahead, free of any constraints. Instead, it is accelerating faster than ever, with fortunes being accumulated in ever fewer hands. But all the discontents – indeed, the anguish and fury that these developments arouse – do not turn against an impossible and inhuman capitalist system but against those who work with words and other means of expression: politicians, journalists, writers – all those who think ‘they understand’, as their detractors argue.

We are living in a time of wrath but also at a time of chatter. So much more reason to care about ‘words and images’.

This article is based on Sven-Eric Liedman’s keynote speech at Ord&Bild’s 125th anniversary event on 4 November 2017 – a day of seminars on ‘The Role of the Cultural Journal in the Public Sphere’.

Ord&Bild 3–4/2017