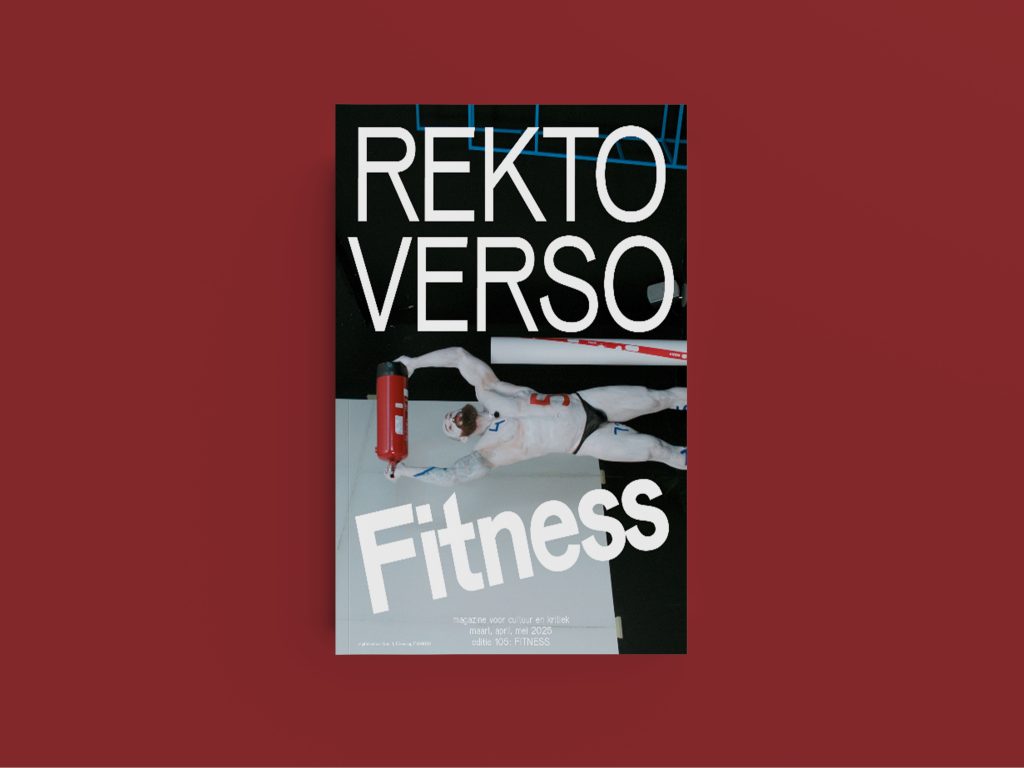

In its latest issue, Flemish–Belgian journal rekto:verso delves into the politics and aesthetics of fitness. From strength training and bodybuilding to pole dancing and yoga, it examines how fitness practices both reinforce neoliberal values and dominant beauty standards, as well as offer space for resistance and self-discovery.

In a piece on action movies and the male physique, film theorist Lennart Soberon looks at how the brawny bodies of action heroes are ‘canvases upon which the political power relations of their time are sketched’. The fact that we find heroism in disregarding the body’s limits, he argues, speaks volumes about our society.

Action films build to moments of (auto)mutilation ‘with masochistic fervour’, writes Soberon. More than bulging biceps, the genre is characterized by the suffering of its heroes, who are invariably subjected to torture and agony. ‘On the anvil of victimhood, the hero is forged into a man.’

Images of unyielding masculinity also fuel national myths. For example, when Ronald Reagan called for effort and perseverance in times of austerity, the bodies of Hollywood actors such as Sylvester Stallone functioned as ‘a metaphor for the heroic recovery of the US’.

Today, the genre reflects a neoliberal worldview that has ‘burrowed deep into our bodies’, writes Soberon. The Cartesian dualism that in capitalism allows workers’ bodies to be viewed as instruments to be squeezed for profit also operates in action cinema, where bodies are tools rather than living entities.

The films, which never show bodies resting or recovering, ‘present us with a fantasy of perpetual growth, mobility and self-optimisation’. In this century of self-improvement, Soberon writes, we have all become action heroes to some degree, exploiting ourselves for recognition and reward.

#CripYoga

Under the social media hashtag #YogaForAll, yoga practitioners are encouraged to be aware of their body’s limitations. But to philosopher and cultural scientist Lisanne Meinen, this accessibility discourse rings hollow. Drawing on crip theory, she explores what it would really take for yoga to embrace difference and disability.

Meinen describes how the welcoming, inclusive discourse of contemporary western yoga remains at odds with its imagery. While it has become common practice to offer aids such as bolsters or belts to people who cannot hold certain poses, the perfect yoga body continues to function as the norm.

Getting as close as possible to the original posture remains the goal, and images of yogis with disabilities are rare. If such images exist at all, they are often produced in the context of rehabilitation. In this way, yoga welcomes disability only ‘as a temporary state of being’, reinforcing the idea of disability as something to be overcome.

Meinen calls for an explicit #CripYoga that does not erase physical differences, but explicitly names them. She sees a possible version of this in Jivana Heyman’s anti-perfectionist approach, which focuses not only on using aids to make a pose more accessible, but also on adjusting the poses themselves. A next step would be to let go of the fixation on the body and focus on the mental health benefits of yoga, Meinen writes.

But even this last step carries dangers, according to Meinen. For her, #CripYoga would also involve actively reflecting on our motives for doing yoga, to avoid falling into what cultural studies scholar Robert Crawford has called healthism, or the moralisation of (mental) health.

Mishima, the fitness guru

In 1968, Japanese author and ultra-nationalist Yukio Mishima committed ritual suicide after a failed coup attempt to restore Emperor Hirohito to power. His death was the destructive culmination of years of physical training, chronicled in his memoir Sun and Steel. Writer and photographer Hugues Makaba Ntoto, a strength-trainer himself, explores why the author’s work remains popular among fitness practitioners.

How can bodybuilding and the destruction of the body be reconciled? Mishima, disillusioned by the materialism of post-war Japan, looked for meaning in ephemeral beauty, which he found ‘most compelling when it was impermanent, rotting or destroyed’.

Mishima’s search for beauty would increasingly focus on his own body, as he turned to bodybuilding and martial arts to ‘transform his physique into an extension of his artistic vision’. The author, who glorified self-sacrifice, began to build ‘the muscles suitable for a dramatic death’. It was at once ‘a fascist instrumentalisation of his body for political purposes’, as well as a search for balance between the intellectual and the physical.

Sun and Steel and modern fitness culture share ‘a self-absorbed belief in one’s infinite and “miraculous” potential’, writes Makaba Ntoto. But while bodybuilding focuses on achieving an idealised aesthetic, strength training centres on building functional strength and resilience. By celebrating process instead of fixating on finality, strength training shapes the body ‘into an expressive form that celebrates life’s possibilities rather than its tragic impermanence’.

Review by Koba Ryckewaert