Coverage of the 100th anniversary of the Russian revolution last year suggested its meaning and significance could be reduced to a few simplistic stances. There were ‘celebrations’ by some left-wing groups and networks. Mainstream commentators explained, once again, that 1917 was a ‘wrong turning’ which led inevitably to the horrors of Stalin’s Gulag prison camps. Perhaps the most common claim was that Marxism is irrelevant now, a set of 19th-century ideas that may have resonated in their time, but can now be consigned to ‘history’.

This last position denies that communism aimed to address problems of inequality and oppression which are still very much with us. But all the key responses to the 1917 centenary obscured how communist politics were always complex and plural. The radical left-wing parties which formed around the world after the Russian revolution tried a great variety of strategies and tactics in their pursuit of revolutionary change in the 20th century. This is underlined by the various different approaches which Marxists took to religion – and it is worth looking again at this record. In both negative and positive ways, the communist experience can suggest effective steps for those who want to promote the cause of reason and apply secular principles in political and social life today.

It is widely held that the Bolsheviks promoted atheism from the moment they took power. However, this is not the case. Lenin’s revolutionary colleagues saw themselves as ‘rationalist’ and ‘scientific’, to be sure, and thorough-going criticism of religious beliefs and of the reactionary social influence of the Russian Orthodox Church was part of this. But atheism was not a significant aspect of their political programme, and there were divisions between Bolshevik leaders about what approach to take to religious believers.

During the Civil War which immediately followed the revolution, there were serious moves to reduce the church’s authority and social position. Bishops and priests were identified as enemies of socialist change in these years of sharp upheaval. Their institutions had, after all, supported the cruel autocracy of the Tsars. But even when there were arrests and executions of religious officials judged to be supporting counterrevolution, these steps were not an attempt to impose atheism. The 1918 legislation separating church and state did not prohibit public worship as such, nor specify that churchgoers should be persecuted on account of their beliefs.

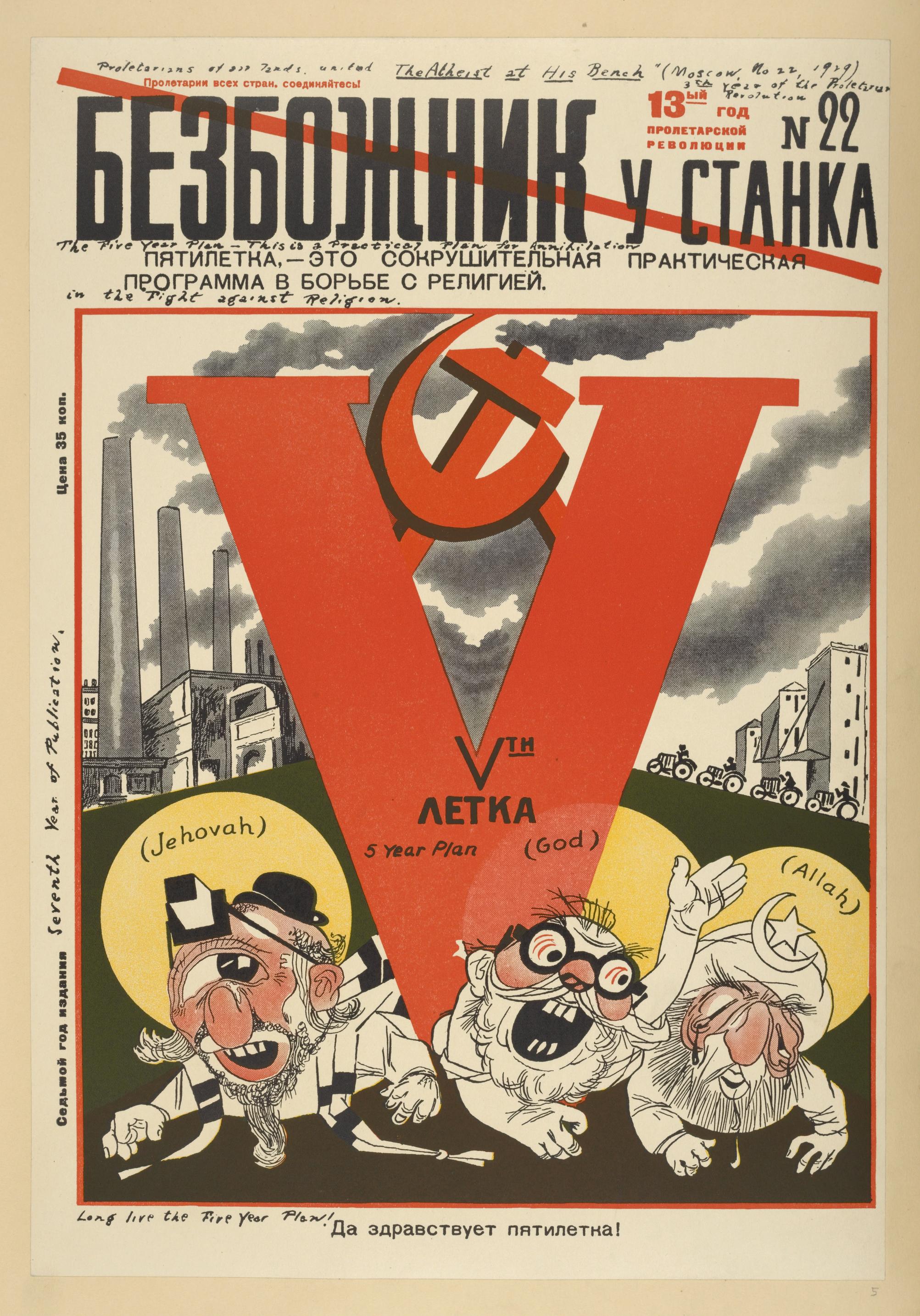

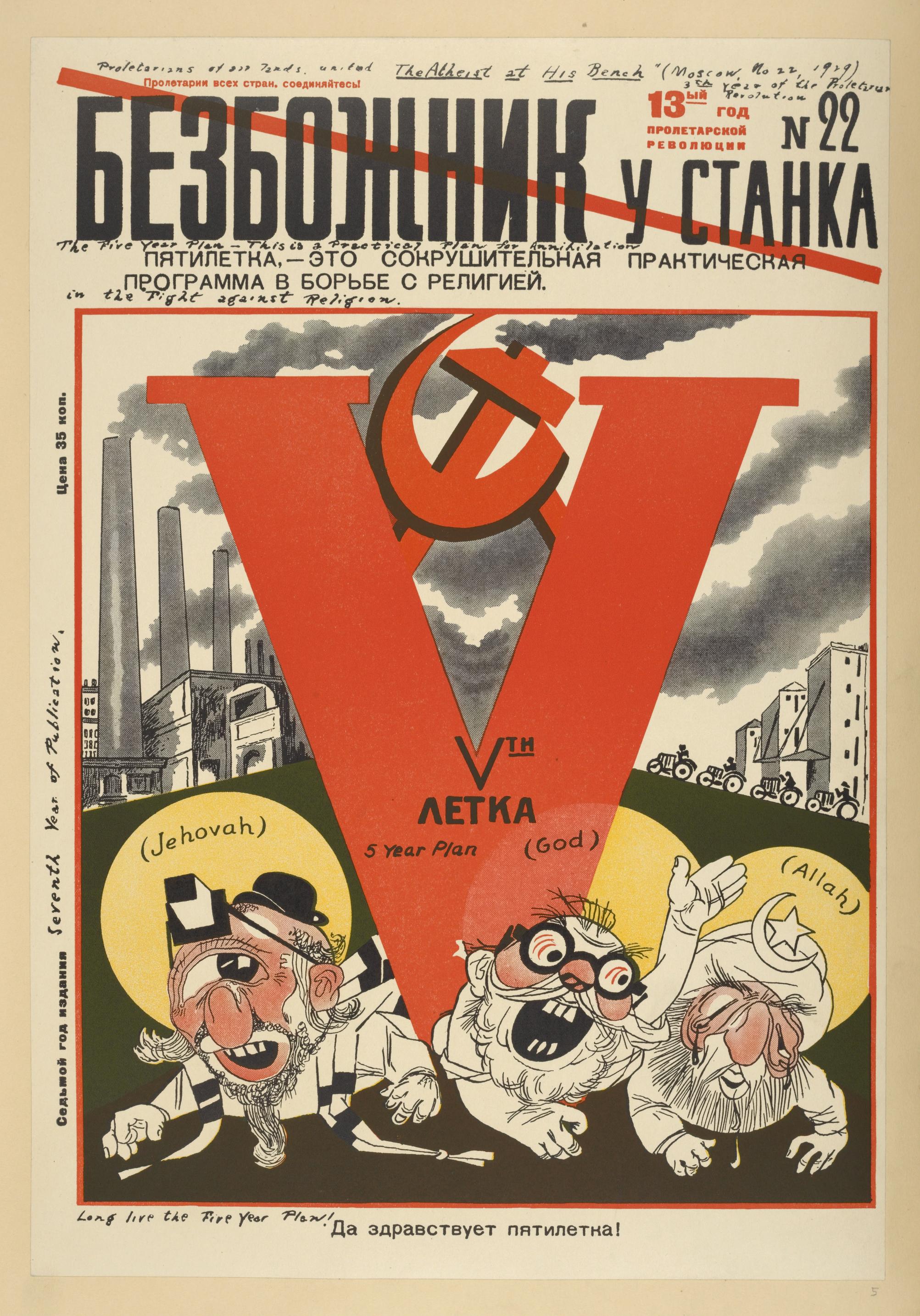

1920s Soviet magazine showing gods of the Abrahamic religions being crushed by the Communist 5-year plan. Photo source: Wiki Commons

Some revolutionary communists actually appealed to people’s religious values with the aim of mobilizing them in support of Bolshevik initiatives. There were initial successes: most of the groupings which made up the Jadid Islamic reform movement in the former Tsarist empire decided to support Lenin’s government. But such potential for alliance-building was undermined by insincere and cynical attempts to engage the faithful. At the Congress of Eastern Peoples, held in the Azerbaijani capital Baku in 1920, the atheist and Communist International leader Grigory Zinoviev played with Islamic concepts, urging anti-imperialist struggle as a form of ‘jihad’. at the same event, the left-wing futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov told bemused Muslim delegates that his maverick views were ‘the continuation of the teachings of Muhammad’.

Compared to such manipulative trickery, the agitators of the League of the Militant Godless represented a model of honesty and openness. From its establishment in 1925, the League published newspapers and magazines, organized debates, lectures and film shows, and sought to persuade citizens that religious beliefs and practices were irrational and harmful. Key political leaders in the mid- 1920s understood that creating the ‘new Soviet man’ would involve persuasion rather than repression of the faithful. Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first Soviet minister of culture and education, had said that ‘religion is like a nail – the harder you hit it, the deeper it goes into the wood’.

The revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky wrote sensitively about the need to acknowledge the real human needs and emotions which religious ceremonies addressed, particularly around birth, marriage and death, and explained that these could not be simply ‘opposed’. New customs and cultures had to be invented and promoted to give meaning to key moments in family, community and national life. Trotsky was also clear that ‘compulsion from above’ would not work in this area. Supporting and developing ordinary peoples’ creativity would be the key approach.

On this basis, there were campaigns urging people to demonstrate their liberation from religion – both Christian and Islamic. One such drive took place in Uzbekistan in 1927, when thousands of women responded to communist calls to assert their rights by taking part in small gatherings and large public rallies where they threw off their traditional dress and face veils. Research has shown that this movement in fact involved a mix of choice, pressure and force. It also provoked a traditionalist backlash and murders which terrorized women into re-veiling, and confirmed the resistance which overt drives to ‘modernize’ would face.

From the end of the 1920s, Soviet economic policies centred on a programme of rapid industrialization, and the forced collectivization of farming. These both expressed and further developed a strong social base for Stalin’s political dominance. And now systematic and very aggressive anti-religious strategies were pursued across the Soviet lands. New laws restricted religious freedoms. Churches were closed and clergy were arrested in large numbers, and many were sent to the camps and executed.

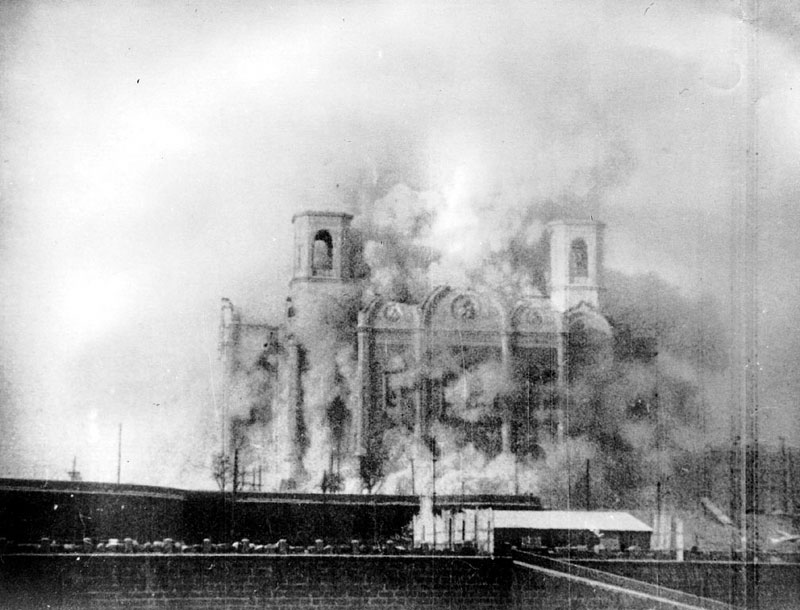

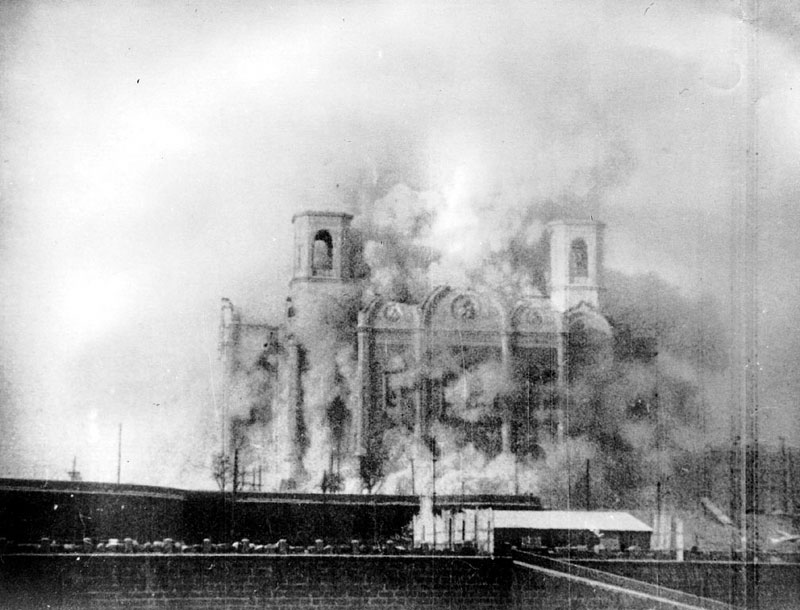

Demolition of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow on the orders of Stalin, 5 December 1939. Source: Wiki Commons

Stalinist repressions in the 1930s happened at the same time as communist parties in European countries promoted the ‘Popular Front’. Marxists now sought alliances with others, partly as a defensive strategy against fascism following Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany. In France, the communist leader Maurice Thorez declared that his party held an ‘outstretched hand’ to the Church and believers in his predominantly Catholic country. Italian communists urged Catholics to join them in struggling against Mussolini’s regime, stating that their party had ‘absolute respect for religious opinions’. (It should also be noted that this was also the period of the Spanish Civil War, in which supporters of the communist and other left-wing parties in the republican coalition did attack and kill many members of the clergy, and burned some churches and convents. This was largely a reaction to the church’s identification with Franco’s right-wing nationalists who were fighting, successfully and brutally, to overthrow the democratically elected republican government.)

From the late 1930s, religious policy changed in the Soviet Union itself. The Russian Orthodox Church and some other denominations were granted varying degrees of toleration, on the understanding that they would support – or at least not oppose – government policies domestically and abroad. After the Nazi invasion in 1941, Stalin revived the Russian Orthodox Church so as to help secure patriotic support for the war effort. The post-war period saw periods of conciliation and uneasy accommodation, alternating with successive rounds of anti-religious campaigns and some periods of state repression.

Similar zig-zags and contradictory approaches shaped government policy in the other countries run by communists after the Second World War. Enver Hoxha’s regime in Albania was the only such place which consistently tried to outlaw and entirely suppress all religion, with Islam being the main target. Hoxha’s approach extended to policing the dress and hairstyles of the few visitors to the country. These were usually relatively sympathetic members of Marxist groups. But any beards worn by left-wing men visiting Albania in the 60s and 70s had to be shaved off at the border post as a condition of entry, for fear that they might have been interpreted as an expression of Muslim culture.

Italian communists were more Catholic than atheist

In total contrast, the development of more liberal, inclusive and democratic political styles amongst West European communists in the post-war decades saw in- creasing overlap and interaction with church congregations. In 1962, the Italian Communist Party determined that ‘not only can people of the Christian faith support a socialist society but, faced with the dramatic problems of the real world, their desire for a socialist society may be stimulated by the sufferings of the religious conscience’. By the 1970s, the party had more Catholic members than atheists – and this helped build popular support. In the ‘red’ region of Emilia-Romagna, simple arithmetic showed that more Catholics were voting communist than for the centre-right Christian Democrats. This situation had begun building up even during the years when Pope Pius XII had excommunicated believers who voted for the left. In 1977, party leader Enrico Berlinguer denied ‘accusations’ that Italian communists professed an atheistic and materialist philosophy. He described his party as ‘lay and democratic, and as such not theistic, atheistic or anti-theistic’.

Similar positions were taken by Spanish communists as they helped move their country on from Franco’s dictatorship. Manuel Azcarate stated that ‘within our party there is no difference between a communist who has religious faith and one who has not. The two attitudes are equally communist.’ The party leader Santiago Carrillo, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, sought explicit alliance with Catholics: ‘We have often said Spanish socialism marches forward with the crucifix in one hand and a hammer and sickle in the other.’ In Britain, there were rounds of ‘Christian-communist dialogue’, reflecting the desire of some church figures to connect with the radicalism of youth counter-culture, and a growing openness to other people’s ideas by some Marxist theoreticians.

Gorbachev declared that ‘believers are patriots’

At the end of the 1980s, communism was brought down through the interplay of its own self-defeating flaws and effective oppositions. In some countries, religion played a big part in these developments. In Poland, Catholicism had long provided the key space for and vehicle of opposition to communist rule. The visit of Pope John Paul II, Karol Wojtyła, to his homeland in 1979 had galvanized a growing desire for social change. Nearly one in three Poles went to at least one of the events at which Wojtyla spoke. He ended his nine-day visit by addressing a gathering of around three million people near Krakow, telling them it was their right to choose their own government and to defend their own faith.

Meanwhile, weak and inept communist forces in Afghanistan had helped cause the debacle which inaugurated that country’s ongoing misery. A series of pro-Soviet political factions had run the government. They had pursued economic modernization, land reform and attacks on traditional marriage and Islamic customs, often using insensitive methods. From the mid-1970s, there were popular rebellions against these policies, from both tribal land- owners and Islamic clerics, which brutal tactics failed to suppress. The resulting infighting between different Marxist groups precipitated the Soviet move into the country at the end of 1979. Moscow’s unsuccessful military action in Afghanistan drained morale and resources, and provided the context for the USA, Saudi Arabia and others to resource Islamist jihadists, on the basis that ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’. Back in the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempts to reform the economy and political culture through ‘perestroika’ and ‘glasnost’ were accompanied by policies which demonstrated genuine respect for freedom of religion and the autonomy of the church. The last Soviet president declared that ‘believers are working people, patriots, and they have every right to express their views with dignity’. On the millennial celebrations of Russia’s conversion to Christianity in 1988, the Communist Party was concerned not to antagonize believers. If this position might once have expressed a generous secularism, demonstrating that the ruling party could afford to be comfortable about recognizing the independence of religious organizations, some now took it as evidence of government weakness and uncertainty, and one more proof that confidence in communist beliefs was quickly ebbing away.

The various different approaches which communists took towards organized religion were shaped by particular social circumstances and political pressures. The most positive approaches were those which drew from the dynamic understandings of religious phenomena which were fundamental to the emergence of Marxism.

Back in the early 1840s, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels met each other through the radical intellectual network of ‘Left-Hegelians’. Its members were inspired by the work of the German philosopher, but rejected the conservative political views which Georg Hegel himself had adopted in his later years. And they were avowedly atheist, following Ludwig Feuerbach’s insight that ‘God did not make man: man makes God’.

Feuerbach, however, did not simply ‘oppose’ religion. He saw it as corresponding to necessary phases in human evolution. Rather than ‘refuting’ religious beliefs, his critical aim was to show how they contained truths which, when fully thought through, could lead to the post-religious state he described as ‘humanism’. In similar ways, Marx was consistently atheist. In Germany at this time, this position fitted neatly with being liberal and tending to the radical left, because of the direct identification between the church and the repressive Prussian state. Nevertheless, Marx was not anti-religious in the sense that he found the beliefs of the faithful irrelevant or uninteresting. His views emerged through radically critical but careful consideration of religion, which he described in a letter of September 1843 to his friend Arnold Ruge as ‘the table of contents of the theoretical struggles of mankind’.

Alberto Toscano, of Goldsmiths, University of London, has written that ‘Marx’s early writings can be understood in terms of his progressive, rapid realization that the attack on religion is always insufficient, or even a downright diversion of attaining its own avowed ends, namely the emancipation of human reason’. In an 1844 article, Marx reflected that ‘the abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions.’

In a striking phrase, Marx insisted that the reason for ‘plucking the imaginary flowers’ from the chains that bind people is not so that they will continue to bear their social oppression and economic exploitation ‘without consolation’, but so that we could ‘throw off the chain and pluck the living flower’.

Such passages illustrate the direction of Marx’s thinking and activity ‘from the criticism of Heaven to the criticism of Earth’. What shaped this shift was not so much the critique of religion, but Marx’s critique of the Left-Hegelian critique of religion. Marx’s key recognition was that religion, and philosophical understandings more generally, are social problems conceived in abstract forms. And this was the insight which he quickly went on to apply to fields he regarded as far more significant than religion: the direction of history, the workings of society, class politics and economics.