Hagia Sophia: Politics before culture

The conversion of the Hagia Sophia was intended as a demonstration of strength to Erdoğan’s conservative Muslim constituency and the wider Islamic world. But calculations of political advantage have also caused the weak response of the West. World cultural heritage has been dealt a huge blow, writes a leading Russian Byzantinist.

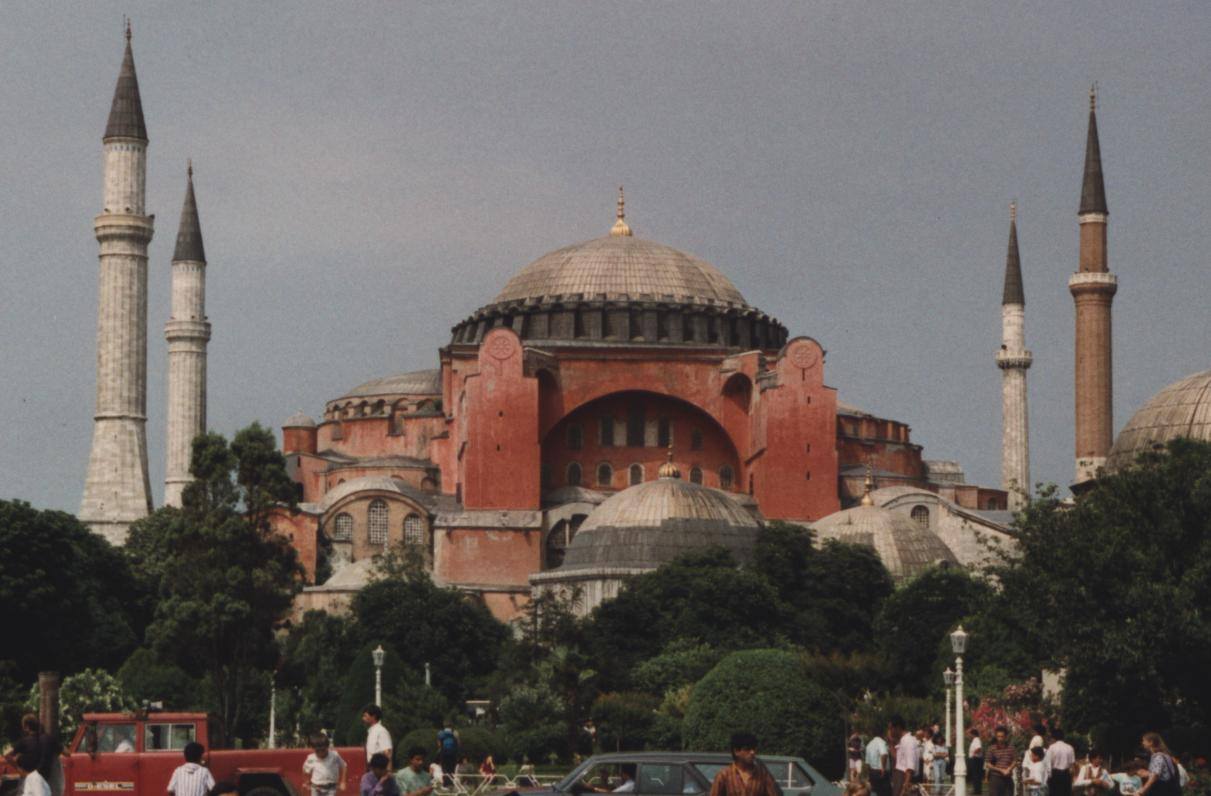

On 10 July 2020, by a decree of the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the basilica of Hagia Sophia – the central church of the Byzantine Empire and the entire Orthodox world, erected by Emperor Justinian in the sixth century A.D. – was turned from a museum into a mosque. The conversion attracted worldwide attention. In a rare show of unanimity, the leaders of the US, the EU and Russia, as well as most international institutions, appealed to Erdoğan not to go ahead with the plan. However, all the warnings were ignored and the first festive Muslim service was held on 24 July, with the country’s leadership in attendance.

Since Hagia Sophia is located on Turkish territory, the Turks have the right to use it for religious services if they wish. However, that is only a superficial truth. The Hagia Sophia has always held a deep spiritual, cultural as well as historical value and is considered to be the most important Christian church, and not only for the Orthodox community. For the whole world, Hagia Sophia represents the principal monument of Byzantine civilization. In 1985, UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site.

Photo by Elgaard from Wikimedia Commons

The Ottomans themselves understood Hagia Sophia’s symbolic significance. The first thing Mehmed II did after his conquest of Constantinople in 1453 was to turn it into a mosque, in a clear symbolic gesture. In 1935, in equally symbolic fashion, the founder of the secular Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, turned the mosque into a museum. This was an unambiguous declaration of his intention to transform the Turkish Republic from an empire based on religion into a secular state that aspired to unify with Europe.

Now, by reclassifying Hagia Sophia as a mosque, Erdoğan is also dealing in symbolism. There is, after all, no practical need to establish another mosque in the centre of Istanbul. The famous Blue Mosque stands right next to Hagia Sophia. Like most Turkish mosques, it was modelled on Hagia Sophia, so impressed were the Muslim architects by this creation from the era of Justinian. There are also many bigger and smaller mosques in the area.

Erdoğan is sending three messages. The first is addressed to his conservative Muslim constituency in Turkey, which overwhelmingly supports the conversion, regardless of the political, cultural and economic damage. They view it as a symbol of victory over the Christian world. What we see here is an attempt to score points before the next general election, in which the victory of Erdogan’s AKP is by no means guaranteed.

Second, Erdoğan is aiming to consolidate his status across the entire Muslim world as the ‘sultan’ of the Muslim countries of the Mediterranean region. He has long been positioning himself thus and plans many of his foreign policy goals in order to enhance this status.

Finally, it is a gesture aimed at the Christian world, Europe and all international institutions categorically opposed to this act. Everyone is perfectly clear that this is not merely the transformation of a museum into active sacral space. What we are seeing is Erdoğan and the Turkish Republic demonstratively rejecting the direction set by the ‘father of the nation’, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, nearly a century ago.

What does the conversion mean for world culture?

Hagia Sophia is also, of course, of immense architectural and aesthetic significance. Abbot Suger, who conceived and built the first Gothic church on the outskirts of Paris, the Abbey of Saint-Denis, wrote that he was inspired by Hagia Sophia. What Abbot seemed to have had in mind was the unique light architecture of the basilica of Constantinople. In the tenth century, the Russian envoys of Prince Vladimir were stunned by the image of light and space created by this unique building. As reported in the Primary Chronicle, it was this impression of dwelling ‘between heaven and earth’ that contributed to the decision to adopt the new faith from Byzantium.

Instead of professional builders, Justinian entrusted the architecture to two renowned mathematicians and opticians: Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus. The forty windows supporting the central dome create a ring of light that illuminates the dome by day and night. The light creates a shining cloud beneath the dome, symbolizing the presence of God – the core image of the Byzantine empire, known as kavod in Hebrew and doxa in Greek.

Photo by Erik Törner from Flickr

The mosaics further amplify the resonance of the basilica as a space. Before the ninth century, when the worship of icons was introduced, the cathedral had contained no figurative mosaics. Instead, the image of God was created by the dramaturgy of light; any ‘pictures’ on the walls and columns would have been superfluous. This light effect will remain even once the mosaics have been covered.

What about the practical implications of the conversion for scholars and ordinary visitors alike? Visits will be limited to periods between prayer times, which take place five times a day. A significant part of the building will be inaccessible, as is also the case with the Blue Mosque. The main mosaic icons on the altar have already been covered by curious drapes that disfigure the historic space. During the Ottoman period, the mosaics were daubed over with white lime and were first revealed to the world as a result of the restoration carried out in the early 1930s. The American archaeologist Thomas Whittemore not only covered the cost of the restoration but also published the resulting research material. This marked the start of the serious study of the Hagia Sophia by leading scholars of Byzantine art and culminated in the basilica being turned into a museum. This magnificent achievement has now been reversed.

Photo by brewbooks from Flickr

Other visible losses include the unique marble floor, most of which has been preserved since the sixth century. Its study is crucial to the understanding of the original construction of the sacral space of Hagia Sophia. The entire floor has now been covered by carpets.

Photo: Myrabella. Wikimedia Commons

Photograph: Myrabella Derivative work: Myrabella / Public domain

The conversion of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul is not the first such case. The Hagia Sophia in Trabzon was converted into a mosque seven years ago, having been a museum since 1964. The magnificent thirteenth-century frescoes in the narthex (entrance) can still be viewed, but all those within the church have been covered by drapes. The frescoes in the lower part of the dome have also been hidden from sight.

The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul will likewise be largely deprived of its scholarly significance. After the Turkish authorities completely ignored a letter written by leading Byzantine scholars, stating in detail the damage that its loss of museum status would cause, the World Congress of Byzantine Studies, which was due to be held in Istanbul in August 2021, was postponed by a year and moved to a different location. It is likely that the question of removing the Hagia Sophia from the UNESCO list will also be raised.

As a museum, Hagia Sophia had been generating tens of thousands of euros of revenue annually. To say nothing of the indirect impact on tourism in general: many people are drawn to Istanbul precisely to visit Hagia Sophia.

The Turkish authorities are fully aware of all this. For the past four years, they had regularly raised the prospect of conversion. Now they have carried out their threat. The result is what virtually the entire world regards as a cultural disaster. It has also served to escalate what many see as an ongoing war between Muslims and Christians. Kirill, Patriarch of Moscow, declared that ‘a threat to Hagia Sophia is tantamount to a threat to the whole of Christian civilization, to our spirituality and history’.

Time will tell whether Erdoğan’s calculations pay off. He has one last powerful political card to play: Turkey’s departure from NATO. This threat probably explains why the West’s reaction has been so soft, despite the strong warnings sent earlier. Western politicians will likely try to forget about the transformation of the museum of Hagia Sophia into a mosque. Politics has trumped everything else.

Published 14 August 2020

Original in Russian

Translated by

Julia Sherwood

© Aleksei Lidov / The Institute for Human Sciences / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Giving back the Bronzes

Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik 1/2023

How Germany is leading the way on the restitution of the Benin Bronzes; why nation state parochialism prevails over a European fourth estate; and how radical climate activism is bringing out the worst in Cold War conservatives.

What’s in a word, a term, a meme, a full-blown narrative? At a moment of Russian unilateral ceasefire for the Orthodox Christmas, considered by many Ukrainians as hypocritical, Eurozine authors take an investigative look at the rhetoric of war and Russia’s victim narrative.