Bankrupt

Wespennest 189 (2025)

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Jonathan Bousfield talks to three award-winning novelists who spent their formative years in a Central Europe that Milan Kundera once described as the kidnapped West. It transpires that small nations may still be the bearers of important truths.

Thirty years ago, Czech novelist Milan Kundera dealt with cultural estrangement and its consequences in his celebrated essay “The Tragedy of Central Europe” (first published in the French journal Débats in November 1983, then in the New York Review of Books the following April), sparking off a long-running debate about the fate of European cultures caught on the “wrong side” of the Cold War divide.

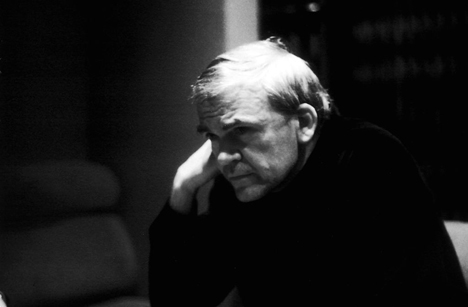

Milan Kundera, 1980. Photo: Elisa Cabot. Source:Flickr

Kundera’s essay initially made for pessimistic reading. Not only did it argue that Central Europe constituted a “kidnapped West” abducted by an alien, Byzantine-Bolshevik civilisation, but it also claimed that the rest of the continent was in too deep a state of decadence to be fully aware of what it had lost. What initially looked like a requiem, however, soon gained an altogether more optimistic sheen. Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Kremlin, the Soviet Bloc showed signs of opening its windows and then the multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan Central Europe eulogised so evocatively by Kundera was quickly re-spun as a symbol of what Europe could be again, rather than what had forever been left behind.

Thirty years on, most of the countries in Kundera’s Central Europe have been integrated into the European Union and NATO, and the very term “Central Europe” is no longer necessary, either as an anti-Soviet rallying cry or a badge of cultural belonging. However, the cultural concerns addressed by Kundera have not necessarily gone away simply because the context has changed. Europe is still sandwiched between two superpowers with differing worldviews, and small nations can still be the bearers of important truths.

Both a successful novelist and an outspoken public intellectual, Milan Kundera had been blacklisted by the Czechoslovak regime during the period of “normalisation” that followed the Soviet invasion of 1968. Immigrating to France in 1975, he enjoyed huge success with the novels The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979) and The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), both of which brought Czechoslovakia’s recent history to a worldwide audience. It was partly thanks to Kundera’s international popularity that educated Western readers spent much of the 1980s being interested in what went on in the eastern half of Europe. The fate of Central Europe was a key theme when Philip Roth interviewed Kundera for the New York Times Book Review in 1980, so the conversation was well under way before “The Tragedy of Central Europe” appeared in 1984. Around the same time, Antipolitics, the book-length essay about the East-West divide by Hungarian writer György Konrád, was published in English. Konrád’s argument was that Central Europe represented the continent’s last great opportunity to build a social democratic space that would be neither Soviet nor liberal-capitalist in nature. Although this is a utopia, it is well worth revisiting. The New York Times even published a polemic between Kundera and future Nobel Prize laureate Joseph Brodsky about Russian culture and its failings. It is hard to imagine that Western newspapers would ever give so much space to non-English-speaking intellectuals today.

But where exactly was Central Europe? Participants in the debate were fond of stating that Central Europe was not so much a precise region as a state of mind, although for writers like Kundera and Konrád it quite clearly corresponded to the former territory of the Habsburg Empire, the collapse of which was seen by them as an unmitigated cultural disaster. Not just because the Habsburg state seemed to represent a culturally pluralist community of many nations, but also because Vienna prior to the First World War had been the crucible of European modernism.

For the Lithuanian-born Pole Czeslaw Milosz, Central Europe encompassed a whole swathe of territory that ran from “Baroque Vilnius” in the north to “medieval Renaissance Dubrovnik” in the south, encompassing pretty much everything that lay to the east of the Germans but was predominantly Catholic and Jewish in heritage. While the ethnic pluralism of Central Europe was celebrated, there was at the same time a clear view of what Central Europe was not: Orthodox Christian, Islamic or Russian.

Not everybody liked the concept. Austrian writer Peter Handke notoriously dismissed Central Europe as nothing more than a “meteorological expression”. Hungarian novelist Peter Eszterházy declared in 1991 that “a writer belongs to a language, not to a region”. Yugoslavia’s Danilo Kis trod with caution when he wrote in 1987 that “the concept of a Central European cultural sphere is perhaps more present today in the West than in those countries that ought logically to belong to this sphere”.

It is clear that for Kundera Central Europe was in large part defined by its novelists (Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, Hermann Broch and Jaroslav Hasek were his four favourites), and that the act of writing novels was one of the things that helped to define European civilisation as a whole. With this in mind, I interviewed three award-winning contemporary novelists – Tomás Zmeskál in Prague, Yuri Andrukhovych in Ukraine and Miljenko Jergovic in Croatia – each of whom spent his formative years in Kunderian Central Europe but are far too young to belong to Kundera’s generation. I asked them about whether Central Europe was still important and where, if anywhere, it could actually be found.

Born in 1966 of mixed Czech and Congolese descent, Tomás Zmeskal created a sensation with his 2008 debut, the Prague-based family saga Love Letter in Cuneiform Script, winning the Josef Skvorecky prize in 2009 and the European Union Prize for Literature in 2011. Zmeskal was the first of three writers I met and it was clear from the outset that Central Europe was for him a historical curiosity rather than a current concern. Zmeskal did, however, grow up reading Kundera’s novels, alongside other “banned” writers like Josef Skvorecky and the Russian Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, whose One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch was published in Czech in the 1960s before being withdrawn from public libraries after 1969.

“By the 1970s, there was a notion that if the authorities caught you reading both Kundera and Solzhenitsyn they were really going to be very nasty,” he remembers. Pretty much everything worth reading had been forced off the shelves during the “normalisation” campaign of the 1970s, when pro-Soviet communist leader Gustáv Husák clamped down on anything that smacked of subversion. “In many ways the ground for the Prague Spring had been prepared by writers like Kundera, Havel, Seifert and Prohaska”, Zmeskal explains. “So it is no surprise that after the Prague Spring the communists decided that they had to silence writers. And the silenced writers really were the best ones – when I was growing up you couldn’t find anything worth reading in the library.

“I remember reading a 1969 polemic between Kundera and Vaclav Hável as a teenager after finding the original newspapers somewhere in the cellar”, Zmeskal recalls, “and it is a brilliant exchange of views between people who were at the peak of their powers.” Kundera accused Hável of moral exhibitionism, encouraging people to indulge in futile acts of resistance; while Havel considered Kundera’s faith in culture to be excessively romantic. “It was a period when Czech intellectuals really mattered, whereas nowadays they don’t. And there is a certain discontinuity in Czech intellectual life anyway: Skvorecky lived in Canada, Kundera is still in France; few of our generation have ever met writers like this in person, and I know very few older colleagues have ever spent drinking time with them.”

The former Yugoslavia was the only communist country in which Kundera’s writings were freely available. His novels were enthusiastically devoured by a young Miljenko Jergovic. Born in Sarajevo in 1966, Jergovic is the most widely-translated of Croatia’s contemporary novelists. His latest book, the monumental part-novel, part family autobiography Rod (The Clan), was published in Croatia at the end of 2013.

“In the Yugoslavia of the 1980s, Kundera was an intellectual best-seller”, Jergovic remembers. “And by no means was he just for intellectuals. By about 1985, just about everyone who read books at all was reading Kundera. Regardless of what people might have said, Kundera wasn’t treated as a subversive writer in Yugoslavia. He was to us a witty and very realistic author and virtuoso, whose novels, or episodes of them at least, deserved to be re-told and shared with one’s friends.”

The “Tragedy” essay was published in Slovene in autumn 1984 and in Croatian the following year. Throughout the late 1980s, the Yugoslav press was full of the debate about Central Europe, largely because Slovene and Croatian writers saw it as an opportunity to differentiate their cultural space from the other, “Balkan” Yugoslav republics. Indeed, contemporary Croatia is one country where the idea of Central Europe still hovers in the background whenever cultural identity becomes the subject of public debate.

Adherence to a Central European idea often says more about where you don’t want to be than about where you actually belong. As Miljenko Jergovic says, “It’s the context that defines our positions on Central Europe, turning every conversation about it into a reactive conversation, as if ducking blows in some imaginary boxing match.”

If there is one place where the debate still makes Kunderian sense then it is Ukraine, a country that still straddles the historical fault-line separating Central Europe from the “Byzantine” East. It is a country whose eastern half has been in the Russian cultural orbit since at least the seventeenth century, but whose western half spent much of its history under the Lithuanian Grand Dukes, Habsburgs or Poles. Here, the debate about belonging to Central Europe, or indeed any Europe, remains very much alive.

Born in Ivano-Frankivsk in 1960, Yuri Andrukhovych is one of the most prolific and influential Ukrainian literary figures, with five novels and numerous collections of poetry and essays to his name. He was awarded the Herder Prize in 2001 and the Angelus Prize for Central European literature in 2006. My conversation with Andrukhovych took place in a Lviv café several months before the Euromaidan demonstrations took off in Kyiv – the benefit of hindsight only makes his observations even more pertinent.

“Maybe it’s in the nature of Ukraine,” he says. “It’s simply too big to be absorbed into some kind of European standard. In one half of the country people don’t have any idea about any kind of European values; while here in Lviv, for example, people talk about them all the time.” Andrukhovych is aware that the concept of Central Europe means little to the predominantly Russian-speaking populations of the eastern Ukraine.

“We can’t unite Ukrainians around some kind of Central European idea; it has to be a general Ukrainian idea. So we have to do this work with other parts of Ukraine first of all, and then propose a common Ukrainian vision of what Europe means to us.” It is a particular tragedy for Ukraine that no government so far – least of all the Yanukovych administration – has succeeded in articulating a general Ukrainian idea that would have at least some meaning to people in all corners of the country.

In his 1994 essay “Erc-Herc-Perc”, Andrukhovych described how his grandmother saw Franz Ferdinand being driven around Ivano-Frankivsk (then Stanislawów in the Austrian-ruled province of Galicia) in an open-topped car, just weeks before his assassination in Sarajevo. It is a key image for Andrukhovych, not just because it provides us with a bit of family history (his Ukrainian and Silesian German forefathers could only ever have met in the multi-kulti world of the Habsburg Monarchy), but also because it places western Ukraine firmly within the Central Europe of archdukes and dashing hussars.

“We needed a certain amount of Habsburg mythology in the 1990s to provide us with an alternative model for the development of a new Ukrainian culture” he explains. “We felt that no one in the wider world really understood that the Ukraine was different from Russia, and re-awakening the Habsburg heritage of western Ukraine served as a useful tool to persuade them otherwise.”

The book Moja Europa (My Europe), co-written by Andrukhovych and Polish writer Andrzej Stasiuk in 2000, was in many ways an attempt to reconsider the nature of Central Europe for the post-1989 generation. The book’s subjective, autobiographical style conveyed a strong sense of shared belonging, but left the question of Central Europe’s nature and whether it is a reality or a utopia very much open. “There was an attempt to deal with the topic in an emotional, poetic, way, free from the traditional geopolitical dualism of East and West”, Andrukhovych now says.

However, the book did include Andrukhovych’s definitive statement on where, geographically, historically and psychologically, Central Europe actually was. “The fact of living between the Russians and Germans is Central Europe’s historical mark of character; Central European fear historically oscillates between the raising of these two alarms: either the Germans are coming, or the Russians are coming. Central European death is a prison death or a concentration-camp death, and by extension a collective death.”

One cannot help feeling that Moja Europa would be a very different book if it were rewritten today: “The drama of the situation between East and West is still very relevant to us Ukrainians, whereas for the Poles it is already decided; for them, further discussion is no longer required.”

Indeed talking to Andrukhovych leaves one with the impression that Ukraine is the last frontier of Kundera’s Central Europe left, where the struggle between a society that aspires to pluralism and an unforgivingly mono-cultural rival is witnessed with indifference by the rest of the continent. According to Andrukhovych, “The Russian sphere openly declares itself to be an alternative to Western civilisation. And for advocates of the Russian sphere there is always a categorical ‘either/or’. There is no room for compromise.”

Some years ago, Yuri Andrukhovych was involved in a project called “Potyah 76” (“Train No. 76”), a website that presented the Central European idea in the form of an international train, each of its carriages devoted to poetry, prose, non-fiction and so on. “The 76 was the train that ran from Gdansk on the Baltic Sea to Varna on the Black Sea, passing through western Ukraine on the way”, Andrukhovych explains. “After the fall of communism, the number of passengers dropped and the route became shorter and shorter – the final version of the 76 ran from the Polish border town Przemysl to the southern Ukrainian city of Chernivtsi before it was finally abolished for being unprofitable.”

It is all too tempting to think of the Central European idea itself as this train, lying abandoned in a railway siding somewhere in western Ukraine, its writers gazing forlornly from fogged-up windows. But as long as they are still writing, it is still worth talking about the train.

Published 7 April 2014

Original in English

First published by New Eastern Europe 2/2014

Contributed by New Eastern Europe © Jonathan Bousfield / New Eastern Europe / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Bankruptcy in nineteenth-century parables of capitalism; billionaires, bankruptcy and the American obsession with money; and why the refusal to accept the end makes life worse.

Parables of violence; memories of dictatorship; perversions of memory: Ord&Bild samples contemporary Latin American literature and photography.