Thomas Gordon introduced his book Principles of Naval Architecture (1784) with a sweeping statement: “As a Ship is undoubtedly the noblest, and one of the most useful machines that ever was invented, every attempt to improve it becomes a matter of importance, and merits the consideration of mankind.” He captured, as a naval architect should, the tall ship’s combination of grandeur and utility as he suggested the importance of its technical refinement and specialization. He noted that the progress of naval architecture could not be confined to this or that nation but belonged properly to all of mankind, whom the ship had helped to connect around the globe. Perhaps most important, he saw the ship as a machine, one of the most useful ever invented. He knew, of course, that the Europe an deep-sea sailing ship – of which the slave ship was a variant – had helped to transform the world from the era of Christopher Columbus to his own time. It was the historic vessel for the emergence of capitalism, a new and unprecedented social and economic system that remade large parts of the world beginning in the late sixteenth century. It was also the material setting, the stage, for the enactment of the high human drama of the slave trade.

The origins and genesis of the slave ship as a world-changing machine go back to the late fifteenth century, when the Portuguese made their historic voyages to the west coast of Africa, where they bought gold, ivory, and human beings. These early “explorations” marked the

beginning of the Atlantic slave trade. They were made possible by a new evolution of the sailing ship, the full-rigged, three-masted carrack, the forerunner of the vessels that would eventually carry Europeans to all parts of the earth, then carry millions of Europeans and Africans to the New World, and finally earn Thomas Gordon’s admiration.

As Carlo Cipolla explained in his classic work Guns, Sails, and Empires, the ruling classes of Western European states were able to conquer the world between 1400 and 1700 because of two distinct and soon powerfully combined technological developments. First, English craftsmen forged cast-iron cannon, which were rapidly disseminated to military forces all around Europe. Second, the deep-sea sailing “round ship” of northern Europe slowly eclipsed the oared “long ship,” or galley, of the Mediterranean. European leaders with maritime ambitions had their shipwrights cut ports into the hulls of these rugged, seaworthy ships for huge, heavy cannon. Naval warfare changed as they added sails and guns and replaced oarsmen and warriors with smaller, more efficient crews. They substituted sail power for human energy and thereby created a machine that harnessed unparalleled mobility, speed, and destructive power. Thus when the fullrigged ship equipped with muzzle-loading cannon showed up on the coasts of Africa, Asia, and America, it was by all accounts a marvel if not a terror. The noise of the cannon alone was terrifying. Indeed it was enough, one empire builder explained, to induce non-Europeans to worship Jesus Christ.

European rulers would use this revolutionary technology, this new maritime machine, to sail, explore, and master the high seas in order to trade, to fight, to seize new lands, to plunder, and to build empires. In so doing they battled each other as fiercely as they battled peoples outside Europe. Thanks in large part to the carrack, the galleon, and finally the full-rigged, three-masted, cannon-carrying ship, they established a new capitalist order. They rapidly became masters of the planet, a point that was not lost on the African king Holiday of Bonny, who explained to slave-ship captain Hugh Crow, “God make you sabby book and make big ship.”

The ship was thus central to a profound, interrelated set of economic changes essential to the rise of capitalism: the seizure of new lands, the expropriation of millions of people and their redeployment in growing market-oriented sectors of the economy; the mining of gold and silver, the cultivating of tobacco and sugar; the concomitant rise of long-distance commerce; and finally a planned accumulation of wealth and capital beyond anything the world had ever witnessed. Slowly, fitfully, unevenly, but with undoubted power, a world market and an international capitalist system emerged. Each phase of the process, from exploration to settlement to production to trade and the construction of a new economic order, required massive fleets of ships and their capacity to transport both expropriated labourers and the new commodities. The Guineaman was a linchpin of the system.

The specific importance of the slave ship was bound up with the other foundational institution of modern slavery, the plantation, a form of economic organization that began in the medieval Mediterranean, spread to the eastern Atlantic islands (the Azores, Madeiras, Canaries, and Cape Verde), and emerged in revolutionary form in the New World, especially Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America during the seventeenth century. The spread of sugar production in the 1650s unleashed a monstrous hunger for labour power. For the next two centuries, ship after ship disgorged its human cargo, originally in many places European indentured servants and then vastly larger numbers of African slaves, who were purchased by planters, assembled in large units of production, and forced, under close and violent supervision, to mass-produce commodities for the world market. Indeed, as C.L.R. James wrote of labourers in San Domingue (modern Haiti), “working and living together in gangs of hundreds on the huge sugar-factories which covered North Plain, they were closer to a modern proletariat than any group of workers in existence at the time.” By 1713 the slave plantation had emerged as “the most distinctive product of Europe an capitalism, colonialism, and maritime power”.

One machine served another. A West Indian planter wrote in 1773 that the plantation should be a “well constructed machine, compounded of various wheels, turning different ways, and yet all contributing to the great end proposed.” Those turning the wheels were Africans, and the “great end” was the unprecedented accumulation of capital on a world scale. As an essential part of the “plantation complex,” the slave ship helped Northern European states, Britain in particular, to break out of national economic limits and, in Robin Blackburn’s words, “to discover an industrial and global future”.

The wide-ranging, well-armed slave ship was a powerful sailing machine, and yet it was also something more, something sui generis, as Thomas Gordon and his contemporaries knew. It was also a factory and a prison, and in this combination lay its genius and its horror. The word “factory” came into usage in the late sixteenth century as global trade expanded. Its root word was “factor,” a synonym at the time for “merchant”. A factory was therefore “an establishment for traders carrying on business in a foreign country”. It was a merchant’s trading station.

The fortresses and trading houses built on the coast of West Africa, like Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast and Fort James on Bance Island in Sierra Leone, were thus “factories” but so, too, were ships themselves, as they were often permanently anchored near shore in other, less-developed areas of trade and used as places of business. The decks of the ship were the nexus for exchange of Africa-bound cargo such as textiles and firearms, Europe-bound cargo such as gold and ivory, and America-bound cargo such as slaves. Seaman James Field Stanfield sailed in 1774 from Liverpool to Benin aboard the slave ship Eagle, which was to be “left on the coast as a floating factory”.

The ship was a factory in the original meaning of the term, but it was also a factory in the modern sense. The eighteenth-century deepsea sailing ship was a historic workplace, where merchant capitalists assembled and enclosed large numbers of propertyless workers and used foremen (captains and mates) to organize, indeed synchronize, their cooperation. The sailors employed mechanical equipment in concert, under harsh discipline and close supervision, all in exchange for a money wage earned in an international labour market. As Emma Christopher has shown, sailors not only worked in a global market, they produced for it, helping to create the commodity called “slave” to be sold in American plantation societies.

The slave ship was also a mobile, seagoing prison at a time when the modern prison had not yet been established on land. This truth was expressed in various ways at the time, not least because incarceration (in barracoons, fortresses, jails) was crucial to the slave trade. The ship itself was simply one link in a chain of enslavement. Stanfield called it a “floating dungeon,” while an anonymous defender of the slave trade aptly called it a “portable prison”. Liverpool sailors frequently noted that when they were sent to jail by tavern keepers for debt and from there bailed out by ship captains who paid their bills and took their labour, they simply exchanged one prison for another. And if the slave ship seemed a prison to a sailor, imagine how it seemed to a slave locked belowdecks for sixteen hours a day and more. As it happened, the noble and useful machine described by Thomas Gordon benefitted certain parts of mankind more than others.

From Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History (New York: Viking-Penguin, 2007), Chapter 2: “The Evolution of the Slave Ship,” 41-45.

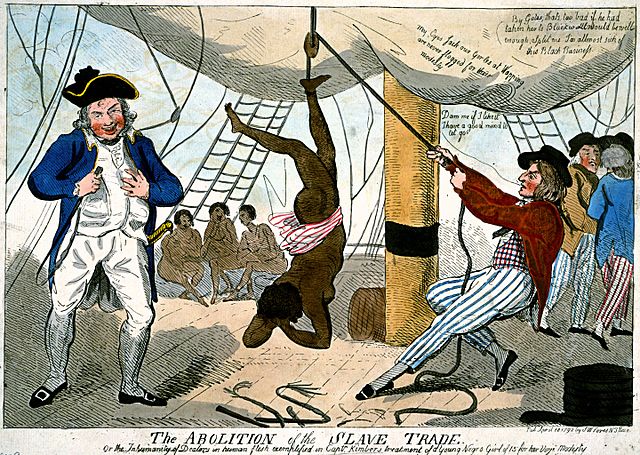

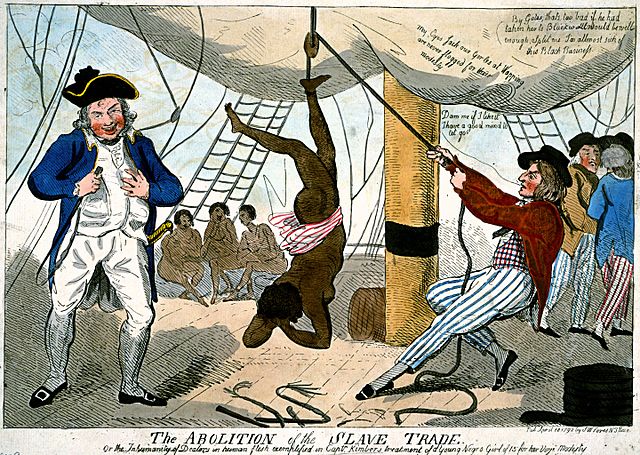

“The abolition of the slave trade Or the inhumanity of dealers in human flesh exemplified in Captn. Kimber’s treatment of a young Negro girl of 15 for her virjen (sic) modesty.” Published by S.W Fores, London, April 10, 1792. Source: Wikimedia

“Ghosts on the waterfront”

Simon Garnett: The ports of Liverpool, Bristol and London were the seat of the British slave trade and where the ships were built that transported slaves from the coast of West Africa to America and the West Indies – the so-called Middle Passage. While 40 per cent of the total number of slaves who made this journey did so in British and American ships, the slave trade was a fundamentally European project – the French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Danes and Swedes all had their slave trading routes and operations. What role did European harbour cities, as the centres of the slave economy, play in cultural Europeanization during the eighteenth century, when the trade was at its height?

Marcus Rediker: As nodes of economic, political, and cultural power, port cities played a central role in the global development of shipping, the creation of blue-water empires, and the rise of capitalism. The Atlantic slave trade was an axis of all three. Merchants gathered in the ports, where they engaged tradesmen to build ships, hired labourers to move cargo, and employed seamen to sail their ships, fleets of which in turn connected them and their commodities – textiles, metalwares, firearms, alcohol – to West Africa and many other parts of the world.

Portuguese and British merchants, strongly supported by their governments, led the way, the former at the beginning of the almost four hundred-year trade, in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century and again in the nineteenth, the latter in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the busiest time of commerce in human beings. Lisbon and numerous Brazilian ports were important. Of the roughly 35,000 known slaving voyages, approximately 5300 began in Liverpool, 3100 in London, and 2200 in Bristol. These three ports accounted for 90 per cent of the British trade; by the late eighteenth century Liverpool was the centre of the slave trade worldwide. The Dutch also played a critical role in the seventeenth century, Amsterdam above other ports with almost a third of the trade, followed by the Zeeland ports, especially Middelburg, then Rotterdam, Friesland and Groningen. Nantes was the origin of almost half of the slave ships that sailed out of France; the upper tier of twenty other ports included Bordeaux, La Rochelle and Le Havre. Seville was the main slaving centre of Spain, Copenhagen of Denmark. In the United States, the tiny state of Rhode Island was the hotspot for trade in black bodies. Any and all nations with a significant fleet of deep-sea sailing ships chased the glittering wealth to be made in the Atlantic slave trade.

If the port city was the world’s most cosmopolitan place in the eighteenth century, the waterfront was the port city’s most cosmopolitan place. The several blocks by the ocean, sea or river were where the commodities of the world market were shipped and transshipped, loaded and unloaded by as motley (that is, multi-ethnic) a collection of humanity to be found anywhere on the planet at the time. From the decks of the ships, to the wharves and the streets, to the warehouses, the grog shops, the taverns and public houses, the waterfront was a “cultural contact zone” of the first and most formative order.

Ports and ships helped to produce deep and lasting cultural change around the planet. One way to measure their power is to look at a map of the global distribution of languages: why does such a large portion of the world’s population speak the languages of a few small countries located on the western promontory of the Asian land mass? Why are people of African descent spread all over the world? The original answer is maritime trade in general, the trade in slaves in particular. The capital of merchants and the labour of seamen, based in port cities, animated vast historical and cultural change.

SG: You have described how the slave ship became a quasi-sovereign entity, with captains and officers exercising a regime of terror over their prisoners – which included not only the enslaved Africans but also, and to only a marginally lesser degree, subordinate sailors. In your account, the slave ship and the temporary society formed during the Middle Passage brought forth in their most brutal form the relations of power, race and class that characterized the phenomenon of slavery as a whole. To what extent did the slave ship regime represent a maritime “state of exception”, with the ports as intermediate spaces between land and sea? And what role did harbour cities play in resistance to these relations of power, which were altered though by no means overcome with abolition?

MR: A “state of exception” that lasted almost four centuries? The slave trade certainly was a crisis for the enslaved Africans, and for the many sailors on slaving voyages who died in roughly the same proportions as their human “cargo,” but it was no crisis for the ruling classes of Europe. On the contrary. And while it is true that slave ship captains had extraordinary powers of life and death over both sailors and slaves, they differed from other ship captains of the time only by degree. All deep-sea ship captains possessed violent disciplinary authority, which was essential to the mass movement of commodities and the construction of the capitalist world market. The ship’s labour system bore similarities to that of the plantation and the industrial factory. Indeed, the ship was something of a “factory”, as suggested in the excerpt above. The slave ship was an ordinary, central part of the Atlantic economy and the seas real spaces where fundamental historical processes played out, and in that sense not so different from the land.

Places like Liverpool and Nantes were notoriously hostile to any and all who opposed the slave trade, for reasons that are not hard to understand: a large part of the population of both cities, and others to a lesser extent, depended on the trade for livelihood and profits. This was true of the maritime artisan who repaired the slave ship as well as the merchant who stocked and dispatched it. When the British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson courageously ventured to Liverpool to gather evidence about the slave trade in 1787, the merchants there tried to have him killed. They failed and Clarkson emerged with greater resolution than ever to study the trade and expose its horrific violence to public view.

Places like Liverpool and Nantes were notoriously hostile to any and all who opposed the slave trade, for reasons that are not hard to understand: a large part of the population of both cities, and others to a lesser extent, depended on the trade for livelihood and profits. This was true of the maritime artisan who repaired the slave ship as well as the merchant who stocked and dispatched it. When the British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson courageously ventured to Liverpool to gather evidence about the slave trade in 1787, the merchants there tried to have him killed. They failed and Clarkson emerged with greater resolution than ever to study the trade and expose its horrific violence to public view.

Merchants and ship captains shunned him as if he were wild beast of prey, but Clarkson eventually found a crucial source of resistance within the city: a small, mixed-race community of dissident sailors, who had sailed in slave ships, experienced the horror, and now wished to tell their stories. His first informant was a black sailor named John Dean, who dramatically stripped off his shirt to show the gentleman the scars caused by a flogging he received while working on a slaver. This encounter, and others like it, had a profound effect on the young abolitionist. The evidence provided by men like Dean was crucial to the growth of an abolitionist movement and to the education of the broader public about the terrors of the trade.

SG: European port districts today draw massive investment in a real estate-based economy, with prestige waterfront developments serving as emblems of harbour cities’ financial power. The extent to which these cities’ wealth historically derives from slave labour tends not to be acknowledged – or, if so, in a sanitized form, playing down the violence that was slavery’s salient characteristic. How far, in your opinion, is European and American society away from a proper reckoning with the history of slavery, and what is the role of the contemporary harbour city in this process?

MR: There can be no doubt that in the aftermath of the civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s and 1970s we have made progress in acknowledging the histories of slavery and racism in western societies. I have great respect for Anthony Tibbles and the rest of the staff at the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool, who courageously defied fierce public opposition to open an exhibition gallery on the Atlantic slave trade in October 1994. It turns out to have been the most popular and broadly educational exhibition they ever mounted, and laid the foundation for the establishment of Britain’s International Slavery Museum, which opened in Liverpool in August 2007. Other museums have slowly followed the example, but what is known about the slave trade by the public in both Europe and the United States remains limited.

We still have far to go, in my view, but there are reasons for hope. Many people around the world increasingly regard the slave trade, and the institution of slavery itself, as not merely unfortunate parts of history, nor even as systematic atrocities requiring condemnation, but as “crimes against humanity” – parts of the past that affect entire societies over many generations. If the slave trade and slavery represent “crimes against humanity,” then there must be criminals who practiced – and continue to practice – these crimes. Who did what to whom and with what long-term effects?

Residents of harbour cities have a special responsibility, and a special opportunity, to answer this question and to reckon with a painful history, for their expensive waterfronts are inhabited by ghosts. The restless, unquiet spirits of a violent past continue to haunt western societies through racial discrimination, poverty and deep structural inequality, all of which have bases in the history of the slave trade. One might say that the slave ships are still sailing, still stalking us. The Atlantic slave trade has had a long afterlife, and we need a truthful accounting of it. A future with equality and justice may depend on it.

July 2012