A geopolitical catastrophe for Ukraine: 1918

What could have happened had a local war for Lviv not drawn forces away from the Ukrainian revolution in 1918? Experimenting with counterfactual history allows us to reconsider simple questions and search for more precise answers.

When we recall 1918, within the context of Polish-Ukrainian relations, the first thing that springs to mind is the Polish-Ukrainian war for Lviv and Galicia. And this is only natural. This war has deeply influenced relations between the two societies for the decades that followed. Interactions between Poles, Ukrainians and Jews – until the horrors of the Second World War – developed under the influence of the memory of November 1918, as Christoph Mick described it in Lemberg, Lwów, L’viv, 1914-1947: Violence and Ethnicity in a Contested City. Poles celebrated the victory and Ukrainians prepared for revenge, while Jews contemplated memories of the pogrom staged by the Polish army when it marched into Lviv and hence feared Polish antisemitism more than Ukrainian antisemitism.

War of all against all

But memory is an unreliable guide to the past. It is selective and treacherous. In this particular case, the memories of the Polish-Ukrainian war deflect our attention away from more significant events. Despite its decisive importance for the fate of Lviv and Galicia for the next two decades, the war did not carry strategic importance for the whole of Eastern Europe. Much more consequential events unfolded further to the east, in Kyiv. There, while the German occupation finally came to an end, the uprising by the Directorate troops – the revolutionary government of the Ukrainian People’s Republic – was spreading against the regime of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky. This uprising was followed by a new campaign of the Bolsheviks against Ukraine. It started in January 1919 and marked the beginning of one of the most tragic years in the history of Ukraine, which could be compared perhaps only with the famine of 1932-1933 or the German occupation of Ukraine in 1941-1944.

It was the year of the “war of all against all”. The Red and White armies of Russia, the French troops, the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (together with the Ukrainian Galician Army, which in summer of 1919 crossed the former Austrian-Russian border and joined the fight for an independent Ukraine after the defeat in Galicia), the great Peasant Army of Makhno1 and squadrons of self-governed warlords, confronted each other on the Ukrainian lands of the former Russian Empire. None of the armies had a decisive advantage. This made the military confrontation exceptionally bloody and tedious. It also presented a Hobbesian scenario where any sign of a functioning state and its monopoly on violence had disappeared from the Ukrainian territory and violence became universal.

The local Jews were the most affected by the horridness of the situation. They became victims of massive anti-Jewish pogroms, a practice that was implemented by all the warring parties without exception, though the lion’s share was carried out by the army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and peasant atamans.2 The mass character of the anti-Jewish pogroms, however, should not obscure the fact that none of the other ethnic or religious groups were spared from violence and that each of them had their own share of victims and perpetrators. Although violence was omnipresent, it also was spontaneous and chaotic. Yet there was still one military-political force that resorted to violence on a regular and systematic basis: the Bolsheviks. This was one of the leading – though certainly not exclusive – reasons why they became the decisive and sole victors in this “war of all against all” in 1919.

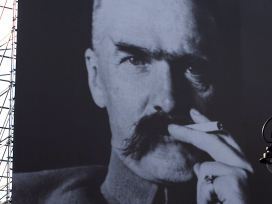

The final attempt to force the Bolsheviks out of those lands, known as the “Kyiv Offensive”, was launched in the spring of 1920 by Józef Pilsudski in alliance with Symon Petliura. This attempt almost ended in the death of the newly born Polish state. After a series of initial defeats, the Red Army pushed forward on the offensive and reached Warsaw. There it was halted by the Polish Army (again, along with Ukrainian forces) during the summer months in the battle that was later called the “Miracle on the Vistula”.

Group of armed workers – participants of the January uprising in Ukraine, 1918. Photo source: Wiki Commons

Counterfactual history

Getting back to 1918 and the Polish-Ukrainian war for Lviv and Galicia in the broad context, it was a local war with a marginal impact. Yet it drew back the forces for the truly decisive battles in eastern Ukraine. The Ukrainian Galician Army was equal to that of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) army in terms of numbers and significantly exceeded it in its organisation and discipline. Tellingly, among the warring parties it was the least involved in anti-Jewish pogroms. By all accounts, if the Ukrainian Galician Army (UGA) happened to be in Kyiv instead of Lviv in the first half of 1919, the outcome of the Bolshevik-Ukrainian war could have been quite different. In the spring of 1919 the balance between the Bolsheviks, the Polish army, the army of the UNR, the White Russians, the ataman squadrons, and the UGA was 30:21:14:10:8:17 (there is no data on the numbers of the Makhno Army). The factual unification of the UNR and Galician armies (formally they were in coalition due to the unification of the Ukrainian and Western Ukrainian People’s Republic on January 22nd, 1919) would have equalised the numbers of Ukrainian troops to that of the Bolshevik Army. Then the fate of Kyiv would have turned out quite differently. In other words, if there was no battle for Lviv then, conceivably, there would have been no need for the Miracle on the Vistula. The Bolsheviks would have been stopped not on the Vistula but on the Dnieper River.

All these contemplations have nothing to do with real history. Nonetheless, there is merit in understanding the counterfactual – which is not about what happened, but what could have happened. It allows us to reconsider simple questions and search for more precise answers. Why the Ukrainian revolution lost is one such question. This topic dominated the interwar discussion among the Ukrainians in emigration. To simplify it out of necessity, there were two answers to the question, each influenced by partisan ideology. The socialist leaders of the Ukrainian People’s Republic explained the defeat by the underdevelopment of the Ukrainian nation crippled by several centuries of Russian influence. Their conservative and nationalist opponents – the latter were predominantly represented by Galician Ukrainians – on the contrary, laid the blame on the leftist elite. They contended that instead of rigorous state-building, the UNR government resorted to socialist experiments and thus condemned the Ukrainian revolution to its defeat. The only untinged moment of such an interpretation was the conservative Hetman state of Pavlo Skoropadskyi in 1918. However, it was destroyed by uprisings led by the Ukrainian socialists at the end of the same year.

This discussion has also been translated into the works of contemporary Ukrainian historians. However, they overlook or underestimate the underlying fact that 1918 was the last year of the First World War. And, hence, the fate of the Ukrainian state was tightly intertwined with the outcomes of the war. To demonstrate this connection, one example may suffice: the Ukrainian right accused the Ukrainian left of postponing the proclamation of national independence. The latter declared the independence of the Ukrainian People’s Republic only on January 22nd, 1918 in the Fourth Universal (the highest law) while the previous three Universals considered an autonomous Ukrainian state as a part of a federal Russia. If we consider this issue from a broader perspective, it becomes apparent that, among the so-called non-state nations of the former Russian Empire, Ukraine was not only far from being the last to proclaim independence – it was the first. Lithuania did the same on February 16th, 1918, Estonia on February 24th, Belarus on March 25th, Georgia on May 26th, Armenia and Azerbaijan on May 28th, and Latvia only on November 18th. All the declarations shared a common purpose: to insulate themselves, under the umbrella of German occupation, from the menace of Bolshevik aggression.

A propaganda leaflet in support of the Ukrainian People’s Republic; designed by B. Shippikh in Kiev, 1917. Photo source: Wiki Commons

External factors

If the First World War had been won by the Central Powers and not the Allied Powers, Ukraine probably would have remained an independent state. Most likely, however, it would not have been stable. It would have been tormented by political crises and its government would have shown authoritarian tendencies. It would have had tough challenges with national minorities – as happened with neighbouring interwar Lithuania, Poland and Romania. Nonetheless if such a state did appear, Ukraine would not have had either the Executed Renaissance (the executions or repression of Ukrainian writers and artists by Stalin) or the Holodomor famine of the 1930s.

Whichever path the Ukrainian national parties would have chosen, an autonomous transition towards totalitarianism would hardly be imaginable – not to mention the improbability of their decision to exterminate the national elite and peasantry, the two groups that were considered to make up the nation’s foundation. Bolshevism did not have prominent support in Ukraine either before or after the revolution. Even within the small group of the Russian-speaking proletariat, political sympathies were on the side of the Mensheviks – moderate Russian social democrats – rather than the Bolsheviks. Bolshevism was introduced to Ukraine from the outside at the tip of a bayonet. Eventually the question arose as whether the Bolsheviks would have retained power in Russia if they did not have access to Ukraine and its resources.

However the war was won by the Allied Powers. Its members more or less reached a unanimous consensus: they treated the Ukrainian question as an internal issue of the Russian Empire. Moreover the independent Ukrainian state had a pernicious image either of a German satellite or another leftist regime on the verge of national communism. Each of those images considerably reduced the chances of Ukrainian independence receiving international recognition. Ultimately the causes of the defeat of the Ukrainian revolution must be traced not only to its inner weaknesses, but to external factors. Ukraine had become a victim of cataclysmic geopolitics. It does not presume that the Ukrainian state was strong. Yet it was not seriously weak either. Comparative studies show that the 1917 Lithuanian revolution was weaker in terms of mobilisation than the Ukrainian one, though Lithuania became independent after the war while Ukraine did not. Among the reasons for that, one should mention the fact that the Lithuanian question did not have as much geopolitical weight as Ukraine. Firstly, it was not so closely connected to the Russian question: it was easy to imagine Russia without Lithuania, but harder to imagine Russia without Ukraine. Secondly, the geopolitical status of Ukraine was determined by its vast natural and human resources and control over these resources was of great importance for victory on the Eastern Front.

The price of independence

Recently, a consensus emerged among non-Ukrainian historians that the fate of the military and political events in Eastern Europe depended, more than anything, on what was happening with Ukraine and its fate. This was the case during the First World War – and so it remained until the end of the Second World War. But the geopolitical catastrophe in Ukraine – and, in my opinion, for the whole of Eastern Europe – began in 1918.

I would like to end this exercise in counterfactual history with the conclusions presented by Alexander Gerschenkron in his famous 1962 essay Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Though it focuses on economics, it has influenced – and continues to influence – Eastern European historians. In particular, it was due to the fact that Gerschenkron, who was born in Odesa and worked in interwar Vienna, deduced lessons from our region’s past but applied them to a broader historical perspective, which crossed the line of what Bernard Russel called the ‘dogmatism of the untraveled’. The main lesson of the 20th century, according to Gerschenkron, is that the problems of the weaker, less developed nations are not only their problems, they are also – and to a greater extent – the problems of developed nations.

To translate this experience into the language of Polish-Ukrainian relations, it is apparent that the role of the stronger nation historically belonged to Poland. Despite this fact, Poland lost its independence at the end of the 18th century. Still, throughout the long 19th century (1789-1914), it was not considered among the stateless nations, as Ukraine was. This was mainly due to the fact that Poland managed to preserve its rather numerous political and cultural elite. The presence of a political and cultural elite is the main criterion for a state-like character of a nation. Polish culture was widely recognised in Europe, and its aspirations for independence in the 19th century appealed to many European governments and parties. And, moreover, no matter who would have won the war in 1918, the Allied or Central Powers, both sides were ready to recognise Polish independence.

This was not the case for the Ukrainians. Their nation was rural, their culture young and unknown to the outside world. By 1914 the geopolitical significance of the Ukrainian question was close to zero. They had to take their chances during the war and the revolution – but unfortunately, and ultimately, with deplorable results. When the Polish people celebrated the 100th anniversary of statehood in November last year – a much deserved and undoubtedly important day – they should remind themselves that their victory partially came at the price of the defeat of other weaker nations. National selfishness yields benefits only for short-term goals. In terms of long-term objectives, it brings more trouble than solutions. It is, surely, one of the main lessons of history – regardless of which scenario, real or counterfactual, we choose to examine.

Also known as the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine, or the Black Army, Makhno’s group was composed of both peasants and workers dedicated to establishing an anarcho-communist society – editor’s note.

Author’s note: I deliberately do not provide detailed dates and statistics in order not to distract the reader from the arguments – except when it is important for the argumentation of the main theses of this article.

Published 3 January 2019

Original in Ukrainian

Translated by

Margaryta Khvostova

First published by New Eastern Europe

Contributed by New Eastern Europe 2018 Winter © Yaroslav Hrytsak / New Eastern Europe / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

More than independence

Poland and 1918

Poland regained its independence after the First World War. Despite developing multiple ambitious visions, it failed to recreate its former state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and to reconstruct the map of western Eurasia.