On October 12 2018, the Hungarian government forcibly discontinued university programmes and the MA in Gender Studies through Decree No. 188/2018 (X. 12.), published in the Hungarian Bulletin. Since the announcement did not explicitly name the programme, instead only cryptically referred to a decision to delete Line 115 of the list of accredited master’s degrees, this was a clandestine move. The document says the entrance examination has been cancelled from the 2019/2020 academic year onwards, but the two batches of students who were already enrolled may finish the programme and graduate.

The latter, however, applied only to students of the newly accredited MA degree at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, the Hungarian state university. The only other university that offered a Gender Studies MA in English was Central European University (CEU). The CEU degree, however, was not directly affected by the decree revocation. Although the programme was reaccredited as a Bologna-type MA after Hungary’s EU accession in 2004, it still remained a US-recognized degree.

Nevertheless, it was affected by another administrative decision of the Hungarian government impinging on academic freedom: the amendment to the Higher Education Law on 4 April 2017, concerning the conditions for establishing foreign branch universities in the country. This forced CEU to leave Hungary and move to Vienna – taking all the US accredited programmes and degrees with it.

These actions show how the Hungarian government has sought to create a hostile administrative environment for academic research and teaching that’s not in line with its ideological stance.

The government’s decision to delete the programme from the list of accredited degrees came only two years after its launch, with the first batch of students graduating in June 2019. The rushed nature of the decision, and the fact that none of the parties involved was consulted, is evidence of the government’s authoritarian character. The decision was first implemented as a governmental ultimatum via a circular to the Hungarian Rectors’ Council on August 2 2018, giving the rectors of CEU and ELTE twenty-four hours to notify the directors of the MA programmes and invite them to ‘reflect on the bill’.

Contrary to normal legislative practice, the draft the Rectors’ Council received did not offer any justification of the decision, only a short account of the history of the accreditation of the MA degree in the two institutions. A single sentence refers to a cabinet meeting on March 8 2017, which, according to its agenda, allegedly discussed the future of the gender studies programmes. The minutes of the meeting were never made available.

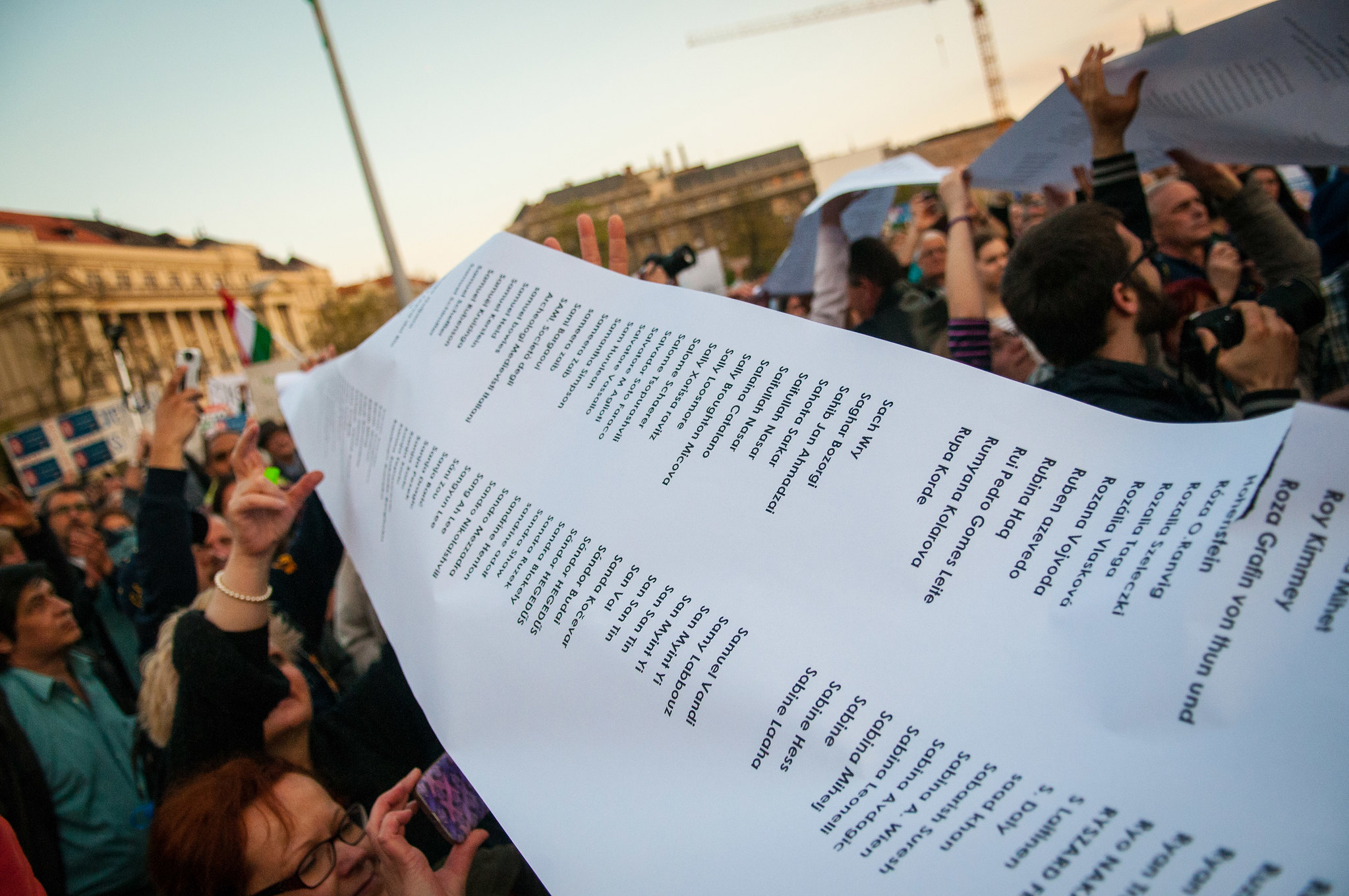

Attendees of the solidarity strike in support of the ELTE Gender Studies MA programme 13 October, 2018 at campus of ELTE Faculty of Social Sciences in Budapest. Photo by Gabriella Csoszó, FreeDoc.

The government’s unfavourable stance became evident in the political media during the previous year. The attacks began in March 2017, shortly after the annual closing date of the university application period in mid-February – right after the first batch of students had applied. The Secretary of State responsible for higher education and research formulated four points which questioned the viability and status of the degree. In line with the usually low level of administrative transparency, the ministry made its arguments public only after an independent MP had submitted a written question to the secretary, asking ‘Whom does the MA in gender studies harm?’. The Ministry argued that there was no demand for the MA degree in Gender Studies on the job market, so running the programme would waste both the national budget and that of the university’s human resources Furthermore, it suggested that the degree was not sustainable given the low number of placements for future students. More importantly, the ministry argued that the degree did not constitute an academic discipline, but an ideology like Marxism-Leninism, and was therefore not appropriate for university-level education. A fourth argument was that the curriculum of the programme stood in contradiction to the government’s concept of human nature.

Why could the ban have such a resounding effect? To answer this question, I will explore the broader context and analyse the populist politics of exclusion that crystallised in the ban as a ‘legitimate’ decision. I argue that it was achieved through three narratives, all articulating a politics of fear. Within the first narrative frame, the ban figures as an expression of the regime’s general anti-gender politics situated in the field of higher education, fitting into a broader strategy restrict academic autonomy and critical thinking. Since its victory in the 2010 national elections, the authoritarian regime of Viktor Orbán has repeatedly attacked research and education. The attacks form a key element in the regime’s efforts to maintain its dominance and right-wing populist politics.

Students of CEU, Corvinus University and other Hungarian universities demonstrated their support for the gender MA programme and students of ELTE on 14 November, 2018. Photo from the event page ‘CEU stands with ELTE‘.

The choice of gender studies over other disciplinary fields is not an arbitrary decision. The official justification of the ban contends that the government has not revoked a discipline, but an ideology. Redefining the meaning of ‘gender’, the key analytical category of feminist scholarship, as mere ‘ideology’ was easier than redefining other social science categories. Firstly, it entered public discourse relatively late, in the wake of the system change in 1989. From the very beginning, it was predominantly brought up to be discredited as an ‘ideology’. This label, which entails party political interests, is difficult to challenge in a country like Hungary, whose academic institutions suffered constant interference from state politics before the system change. Now researchers wish to secure their autonomy with reference to scientific ‘objectivity’. However, their claim to ‘neutrality’ can be counter-effective. The claim may prevent them from seeing that being recognized as scientific means being granted a certain amount of power.

Another reason for choosing gender studies is that it potentially undermines the regime’s authoritarian power that is grounded in an extremely conservative misogynistic gender order. In an August 2018 interview, shortly after the plan to ban the degree was reported in the media, the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff underscored the government’s ideological stance: ‘The Hungarian government is of the clear view that people are born either men or women. They lead their lives the way they think best, but beyond this, the Hungarian state does not wish to spend public funds on education in this area’. In short, the discipline was denied academic merit and relegated into the domain of ideology, its practice a matter of mere political propaganda.

The Chief of Staff’s conclusion that it should be legitimate and reasonable for the government – any responsible government, for that matter – to stop funding a degree that hides its ‘real face’ as a dangerous ideology like Marxism-Leninism implies a further criticism of the term ‘gender’. It makes gender studies seem like a deception, useless compared to ‘real science’ that is defined as ‘productive’. The conclusion resonates with another important part of the regime’s populist discourse: the argument is that anything intellectual is ‘non-productive’ and, as such, parasitic. Sadly, the government has been successful in maintaining their electoral support by downplaying or simply bracketing real socio-cultural problems by targeting institutions and people who are to be blamed for the real or imagined dangers of our daily lives. This aggressive rhetoric of blame has proven effective. The results of the last three national elections show that about half the electorate is receptive to the government’s policies, despite general disillusionment with elite politics for its perceived corruption. Whenever the government wants to reinforce its ‘credibility’, they mobilize right-wing populist discourse, which rallies against anything ‘intellectual’, non-productive, parasitic, or ‘frivolous’, while appealing to ‘common-sense’ and ‘productivity’ in the name of utility and realpolitik.

The second narrative focuses on Central European University. Due to its CEU affiliation, I argue, the ELTE programme did not stand a chance. The alleged ‘threat’ of the ‘Soros university’ in countless government statements implicates the gender studies degree as the instrument of Soros’s ‘liberal propaganda’. It served as ‘evidence’ for the government to legitimize their vendetta against CEU and force them out of the country. After all, the argument that the government should not waste the national budget on ‘non-science’ does not apply to the privately-funded CEU. If the decision to close gender studies had, in fact, been based on budget-constraints, the government could simply have suspended its financial support, making it self-fee paying at the state university. The argument that the government’s ban was ideologically motivated is underscored by their introduction of a new MA in ‘Family Policies and Social Policies’ (sic) in the economics programme of Corvinus University, Budapest in the same ‘Bulletin’ where the removal of gender studies degree was announced, commencing September 2019.

At this point, CEU was already under siege by the government. Chartered in New York State, the university was required to have a teaching campus in the US to be allowed to run study programmes in Hungary. The newly fabricated law on so-called ‘foreign branch campuses’ passed in April 2017. The law was fast-tracked within one week and effectively targeted CEU, the only institution without such a campus out of the seven private institutions in the country.

‘It’s so bad, even introverts are here!’ Sign photographed at the solidarity demonstration ‘Now it’s CEU, who will be next?’ on 03 April 2017 in Budapest. Photo by Gabriella Csoszó, Freedoc.

The law on foreign-branch campuses forced CEU out of the country. Gender Studies, as a US-recognised degree, had to go with it, rendering Hungarian higher education ‘safe’ from ‘liberal propaganda’. By associating gender studies with ‘liberalism’ and CEU, targeting the programme became symbolic for the wider struggle of the Hungarian regime against the European Union and the country’s old neoliberal democratic allies. In that struggle gender studies as a discipline yet again came indirectly to denote and embody all imaginable values that were perceived to undermine the myth of Hungary as the self-styled ‘protecting shield of the old Christian Europe’ who protects its citizens against the danger of ‘Brussels’ and the ‘non-Christian migrant supporting’ hostile EU bureaucrats with no national mandate and with no performance of ‘productivity’.

To make its infamous ‘illiberal democracy project’ work, the Orbán regime and its think tanks singled out George Soros, the founder of CEU in 1991, on two intertwined accounts. Firstly, he was attacked as representative of Western liberalism. The original mission of the university was to promote ‘liberal democracy’ after the collapse of the communist regimes in eastern Europe. It symbolized everything Orbán’s authoritarian illiberal regime has set out to destroy, partly for the sake of the so-called reorientation of the country’s foreign policy towards the ‘east’. Its mere existence threatened to expose the government’s impingement on other universities’ autonomy and academic freedom. Secondly, by denouncing George Soros as the ultimate ‘hideous financial power behind’ CEU’s ‘liberal mission’, and thus the enemy ‘within’, the government harnessed the long tradition of Hungarian antisemitism. Soros’s Jewish family decent made him the ‘ideal’ figure for the government’s right-wing propaganda purposes.

Through systemic vilification, ‘Soros’ has come to mean the ‘enemy’ both within and outside the ‘body of the nation’. In the government’s discourse, the Soros trope functions as the ultimate evil against ‘us’, the Hungarians apparently threatened by his ‘ongoing hideous plotting’. CEU and, by implication, its Gender Studies programme, are presented as one of Soros’ important instruments to weaken the ‘Hungarians’. Seen from within this narrative, it becomes clear that the government’s motivation was not economic or scientific but ideological. In this discourse, the use of the name Soros is sufficient to immediately render CEU and gender studies into sites of ‘hideous ideological conspiracy’ that must be rightly purged by the government in order to protect its ‘people’. Revoking the degree, from within this narrative, emerges as the expression of what Ruth Wodak calls the ‘politics of fear’, the most salient rhetorical characteristics of right-wing populism.

The other meaning of the Soros trope as the enemy ‘outside’ first emerged in the Hungarian government’s official propaganda in the context of the 2015 refugee crisis. That propaganda takes us to the identification of gender (and its study) as an ‘alien ideology’. The image of ‘the frightful, ghastly, monstrous Jew’ has, as I have argued elsewhere, been ubiquitous since summer 2015, when the government began to set up billboards all over the country as part of their anti-refugee campaigns.

The government’s xenophobic and Islamophobic response to the forced migration of people through the Balkan route represents refugees as part of a ‘Soros-plan’ ever since. The billboards reading ‘no migrant to be imposed on us by the European Union’ made the Soros trope a readily available image and effective rhetorical tool whenever the face is shown or the name mentioned. By August 2018, when the Gender Studies programme and CEU were under government attack, the name ‘Soros’ was effectively constructed to denote the merciless ultimate enemy of the ‘nation’. The mere mention of Soros could function as the centre of multiple and often contradictory discourses of fear. It has become an ‘empty signifier’, in Ernesto Laclau’s sense, as a sign that is ‘present as that which is absent; it becomes an empty signifier, as the signifier of this absence’.

Right-wing populist discourses of fear produce social relations between two empty signifiers set up as if they were in a non-reconcilable antagonistic conflict. This takes places through the routine use of hate speech. The exclusionary logic generates an asymmetrical nexus between two equally unspecified positions in a dire opposition: ‘us’ (a kind of populous) and ‘them’ (an unspecified ‘enemy’ threatening to terminate ‘us’). In the homogenized ‘us’, the diverse social groups can recognise themselves as if the ‘same’, although living their lives to different degrees in fear of precarity, of losing their autonomy, lacking trust in the possibility of transparent political institutions. They can conveniently be called upon to come together and re/imagine themselves as ‘we’ who are ‘strong defenders’ of any values the ‘nation’ should stand for in the face of any event, institution or collective that is declared to be ‘a hostile malicious threat’ ‘against us’.

The government’s rhetoric of fear over the past four years has produced constant and explicit references to ‘Soros’, an empty signifier capable of identifying multiple activities and institutions as an ‘alien threat’. This threat is represented by a range of actors, both from ‘within’, such as civil activist organisations, alternative theatres or research institutions, as well as from ‘outside’, such as the European Union or any actor allegedly organising the ‘hostile Muslim migrants’ to conquer ‘our Christian Europe’. It additionally makes for a useful ideological and rhetorical move for the government given that mentioning the trope will safely prevent ‘us’ from acknowledging that ‘our’ sense of fairness and legitimacy disadvantages various others, such as refugees, civil organisations helping them, and educational or cultural institutions of liberal thought trying to build alliances of solidarity. Moreover, it will also save ‘us’ from seeing that the most powerful actor in building its entitlements on our backs is the government itself.

The third narrative concerns migration. It promises ‘us’, imagined as men, to regain our masculinity by fighting to ‘protect our women’ and the Christian family values of the ‘real Europe’ against the ‘other’ men, the homogenized Muslim male ‘intruders’. More indirectly, it calls to defend Europe and its values against the so-called gender and human rights ‘craze’ of civil organisations and academic institutions supposedly ‘behind’ the ‘invasion’, who support and are supported by Soros. This appeal to defending ‘Christian values’ as the ‘real European values’ indexes the rise of a Christian Right in Hungary that can yet again implicate antisemitism intertwined with Islamophobia, conflating the two as if sharing the ‘same’ platform of threat.

Up to this point I have shown that the three narratives conceptualising ‘gender’ as ‘dangerous ideology’ articulate the Hungarian government’s anti-gender politics. The constitutive elements of the meaning of ‘gender’ are the identity categories these discourses mobilize, namely ‘intellectuals’, ‘liberals’, and ‘(Islamic terrorist) migrants’, all accused of threatening the ‘Hungarians’ both from ‘within’ and from ‘outside’ by way of the ‘financial and ideological support’ of a ‘Soros plan’.

Now I will focus on the fourth argument that the Secretary of State for Human Resources presented in March 2017, situating it within the global context of anti-gender populism. The argument contends that the Hungarian government considered the Gender Studies programme undesirable because it is against the government’s view about ‘the nature of the human species.’

Anti-gender propaganda has gained a lead and strengthened its position on the political horizon of right-wing populism on a global scale in response to the crisis of neoliberal capitalism in 2008. This global discourse has presented gender as an ‘ideology’ that seeks to disseminate ‘gay propaganda’ in order to undermine heterosexuality and thereby the reproduction of the nation. The stigmatization of gender (and gender equality) that apparently promotes the demise of the ‘traditional family’ is also present in the rhetoric that is intended to legitimise the Hungarian decree. Calling the concept of gender into question is part of a larger global discourse of discreditation that can be traced back to the United Nation’s Fourth Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995.

Judith Butler, when exploring the historical trajectory of the meaning of sexual difference, singles out the conference as a turning point when the Vatican tried to dislodge the concept

‘from its foundational place’ in critical feminist scholarship, arguing that the category of ‘gender’ for describing women’s status should be removed from the United Nation’s platform as it is simply a ‘code for homosexuality’.

Ever since the conference, the conservative (fundamentalist) Catholic discourse has bolstered a global right-wing populist discourse to pursue the divide that positions citizens into groups where ‘male’ and ‘female’ are radically different. Nevertheless, as far as Europe is concerned, Hungarian state politics has, until recently, been unique in that it was able to mobilise a hostile consensus against ‘gender’ by appealing to ’Christianity’ or ‘God’.

Situated in this context, we can argue that the revocation of the Gender Studies degree is the climax of the current government’s anti-gender politics. Its success was partly possible because the government was able to build on the legacy of a hostile anti-gender politics that emerged in Hungary in the 1990s. The first anti-feminist sentiments in the 1990s were gatekeeping strategies of the political print media associated with right-wing extra-parliamentary political forces. The three main discourses of hostility against ‘feminism’ in the political media in the 1990s were those of anti-Americanism (which invested the meaning of the term feminism with that of an ‘alien intruder’), anti-communism (that perceived feminism as legacy of the ‘old ideology’), and ‘women’s ways of knowing’ that implicates Hungarian feminists as ‘aggressive terrorists’ who impose their man-hating ‘lesbian’ agenda on their ‘sisters’.

That is, the main elements of the current government’s politics of fear were already in evidence in the 1990s and were subsequently reworked and mobilized. This historical context is important in helping to explain the general support for the government’s ban on gender studies.

One should also address the more embarrassing question of self-reflexivity. It is one thing that the general public supported the ban. But why was it that the protest, and enormous international solidarity expressed by feminist and non-feminist professional organisations, institutions and individual scholars, was not taken up more effectively by local feminist actors?

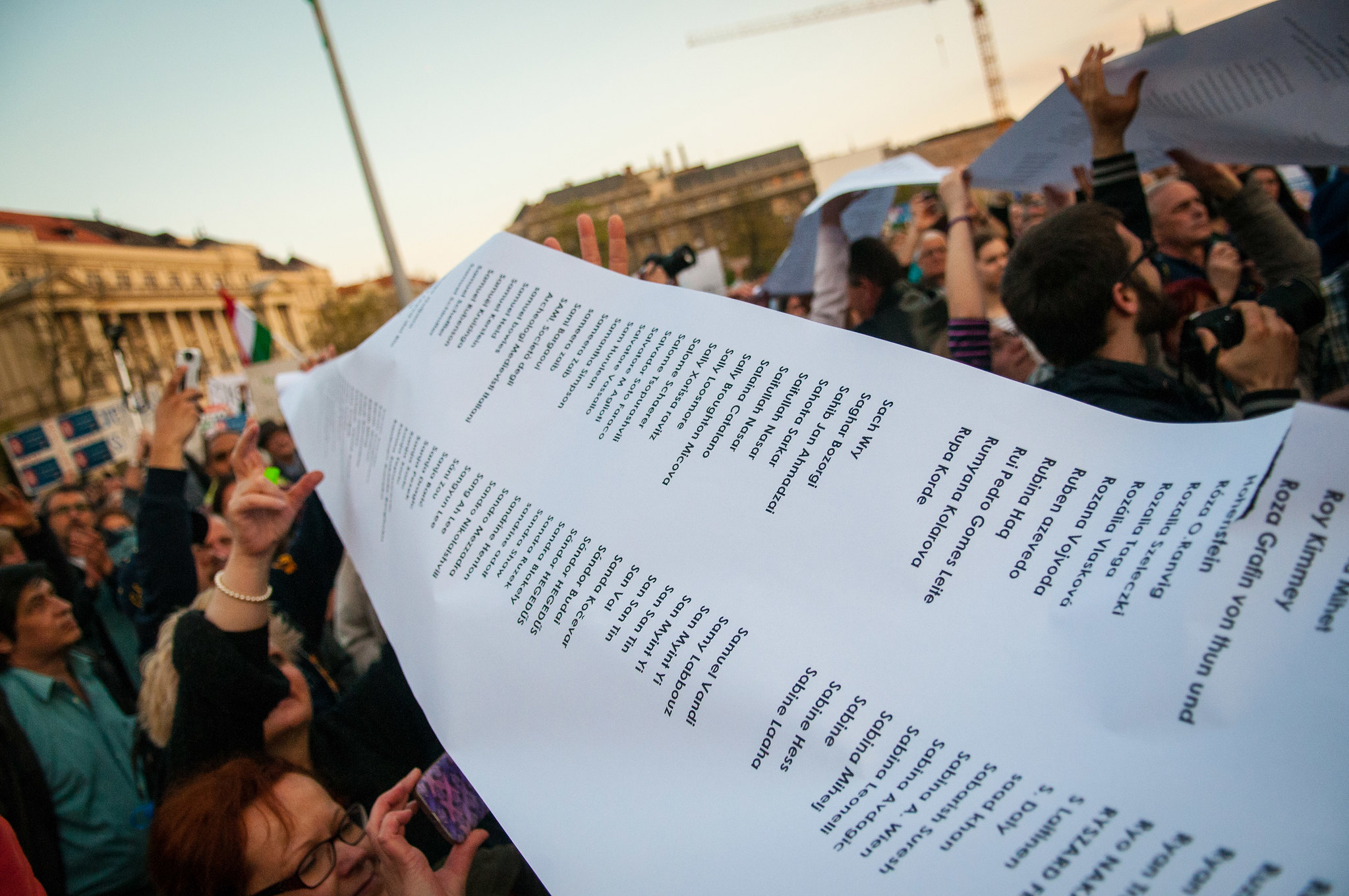

Signatures from a petition supporting CEU, on display at the #IstandwithCEU protest 10 April 2017, Budapest. Photo by Gabriella Csoszó, FreeDoc.

The complex relationship of CEU’s Gender Studies Programme with, and impact on, the emergence and changes to the discipline in the central-east European region are decisive but fall outside the scope of my reflections. Instead, I would like to look briefly at Hungarian scholars’ voices in the public media over the past three decades.

The dominant feminist voices in the 1990s took what I have named a ‘reformist’ position. On the few occasions where feminist scholars were approached by the media on the ground of their understanding of women’s life and the necessary political agenda for change, they would go on the defensive and contend that they did not reject the major elements of bourgeois family values, but wanted to convince their partners to help and make life more liveable for both of them; others would reassure the journalist that they did not question the existence of innate feminine (and masculine) traits, but complained that the ‘wonderful’ female characteristics were acknowledged only in words but not in women’s promotion and recognition.

My premise in taking issue with this (then and now) is that feminism is not about giving housewives their due as ‘partners’ who are pleasurable to live with but changing the social conditions of marriage altogether and the biologist binary of male/female with it. A feminist critique of the government’s current practices of discrediting and stigmatising ‘gender’ cannot stop at validating the (little) reformist self-definition of feminism. In Rosemary Hennessy’s formulation: ‘In positing male and female as distinct and opposite sexes that are naturally attracted to one another is integral to patriarchy. Woman’s position as subordinate other, as (sexual) property, and as exploited labourer depends on [this] heterosexual matrix in which woman is taken to be man’s [natural] opposite’. That is, what we still need to address is the effect of hegemonic power relations of gender between ‘woman’ and ‘man’ that organize sexual difference ideologically in right-wing populist discourse. What is at stake here is how to make ‘feminism’ meaningful without securing a heterosexual social order by harnessing desire and labour in the interest of the expansion of the (cultural) capital and the accumulation of profits (including our own promotion or access to research funds). We must revisit ‘gender’ and explore how far our own theoretical discourses participate in the reification of the heterogendered sexual order.

In short, we must be determined to recentre the concept of gender and with it the charge of ‘ideology’.

This essay is a stylistically reworked version of the article by the same title published in L’Homme Vol. 30, No. 2 (2019), 135-144.