It must have been something like this in Nero’s Rome.

Gossip circulating about the emperor’s mental health; comedians having a field day over his latest faux pas (according to Suetonius, Nero feigned indifference at a comedian who made fun of him ‘for fear of encouraging others to be equally witty’); periodic bribes to the ‘people’ (read: speeches to the Boy Scouts) to beef up the emperor’s ego and make sure that somebody liked him; the public’s growing fear that maybe today he would get the country in real trouble: haven’t we been watching a rerun of this movie for the past six months? Even the torpor that hangs over the American public as they watch the government’s inner circle self-destruct feels like something one reads between the lines of Tacitus and Suetonius as they describe Nero’s hopeless tenure.

After six months of the Trump presidency, the mood in the US is more numb and fatalistic than it was only a couple of months ago. Even though activists on the Left are still working for a few candidates in special congressional elections, and preparing for 2018 – and even though 38% of the electorate still supports Trump and believes that he’s being persecuted by the ‘fake news media’ – both sides seem worn out by the daily uproar, the vague but persistent allegations about the Russian connection, the sabre-rattling from military rivals like Russia and North Korea.

People want to get on with their lives.

If TV and social media have replaced ‘reality’ with a running spectacle comparable to Nero’s shows in the Circus Maximus, by now the show is beginning to feel stale. We know the routines, we’ve heard the jokes, and we’re starting – sadly but understandably – to tune out.

Not that the White House hasn’t tried to supply us with new material. Recently they introduced a new cast member in the person of Anthony Scaramucci, the brash and brief director of communications. Scaramucci’s arrival and departure in less than two weeks seemed like a gesture at turning the Trump show into a movie like Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas: Scaramucci’s heavy Long Island accent, his professions of love for da Boss and foul-mouthed putdowns of his colleagues were an exhilarating parody of mafia films – if those films weren’t already so over the top that they themselves are parodies.

Yet it doesn’t take much effort to look behind the Trump show and cringe at the administration’s performance of the past six months.

The White House is in chaos. The president offers daily pronouncements and nocturnal tweets, but they’re largely ineffectual, and his promises to build up the country’s infrastructure and revise the tax code are pipe-dreams. Heads have been rolling rapidly, and virtually the only advisers left standing are ex-military men like John Kelly, the new chief of staff. At this point the administration looks like a gang of unruly children who recognize that they’re out of control, and the only people capable of imposing discipline are authoritarian alpha males who carry big sticks.

The most worrisome area of administrative blundering has been in foreign policy. In the space of a few months, the position of the US in the world has shifted dramatically. It’s too optimistic to say that no foreign policy has emerged out the White House; anyone can see that decisions are made on the fly, the White House has no idea what it wants except to play to its constituents and reminisce about the election, and while it dawdles other countries move their pawns into spaces that the administration has neglected or eschewed.

So China starts to replace the US as the world power most sympathetic to the issues around global warming; Russia expels American diplomats and plans military exercises on its Western borders; North Korea and the Taliban flex their muscles while the administration stands by clueless, unable to come up with a cohesive plan.

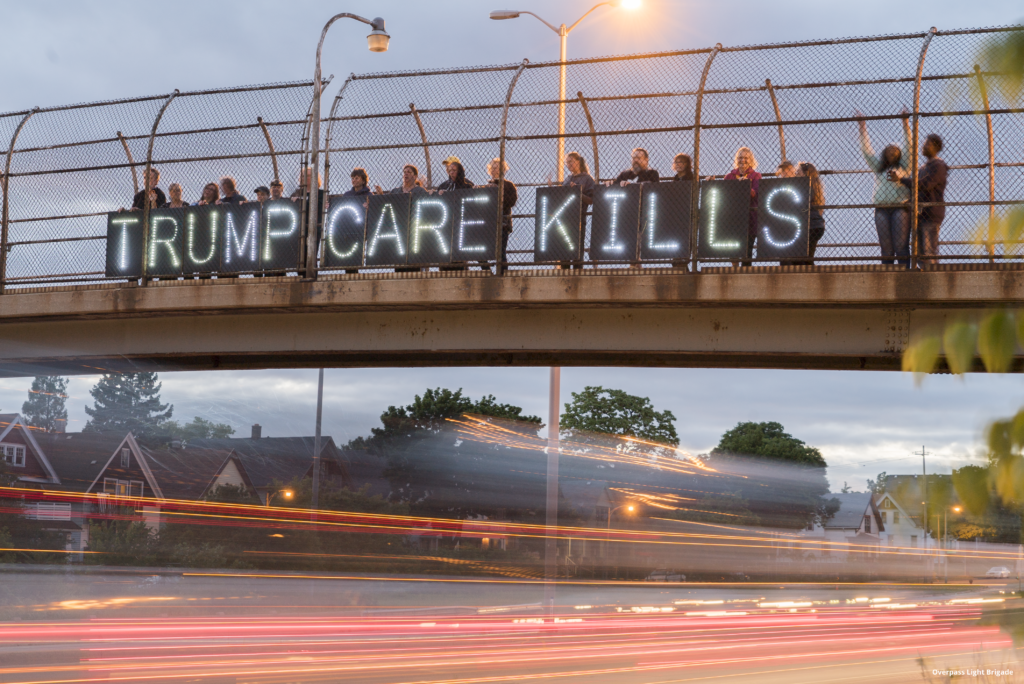

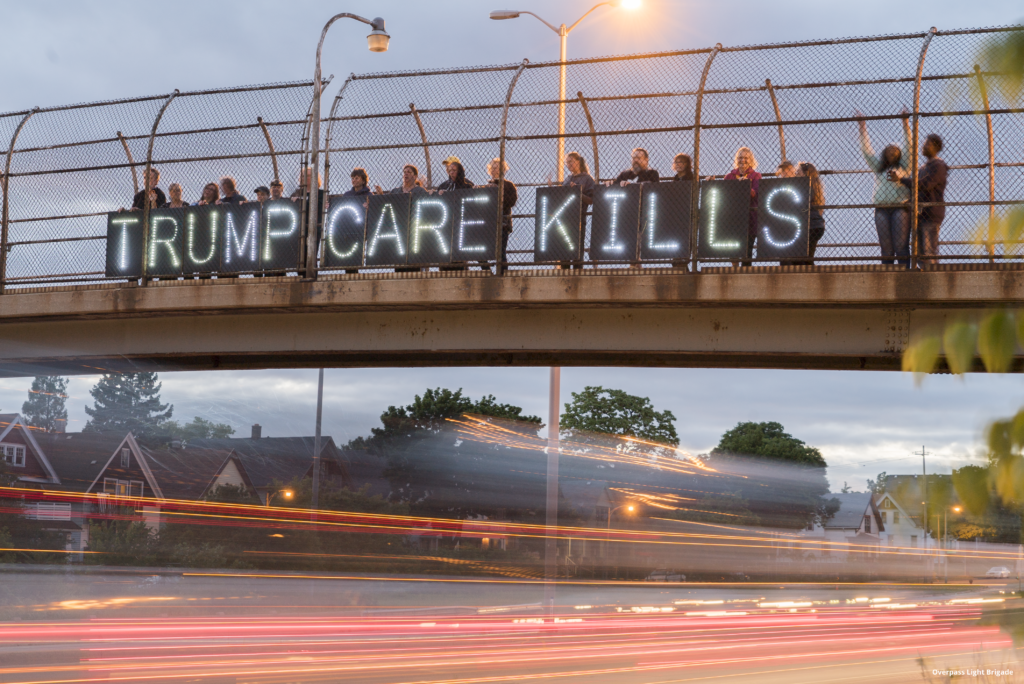

The Congress has gone in several directions at once. On the Obamacare issue, Republicans were so divided that they couldn’t even vote to continue discussion. It was obvious that the only way alterations to the Affordable Care Act could be made was to move it to the left, which made the Republicans’ effort to look like they had something substantive to offer into a kind of tragic foolishness.

Photo: Joe Brusky. Source: Flickr

On the other hand, Congress has shown a degree of initiative lately and asserted itself in a number of ways. It voted by a large margin for sanctions against Russia (which may have been driven more by frustration than foresight), it prevented the White House from withholding federal subsidies to Obamacare subscribers, and for the first time in years it formed informal bipartisan committees to discuss future bills – all without the president’s participation.

A pattern starts to emerge: both domestically and internationally, the world on the other side of the fence around 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue has begun to ignore the president’s bluster and reposition itself as it watches the White House implode.

In one area, however, the Trump administration has been as effective as they’ve been inept in all others.

In what could be loosely defined as the federal bureaucracy – not only the executive agencies that operate in the grey areas of regulation/deregulation but also the hordes of government lawyers and advisers who write policy, choose judicial nominees and direct committees – the administration has put forth a conservative agenda that the media have pretty much ignored.

Under the leadership of ex-Senator Jeff Sessions, Trump’s favourite punchbag at the moment, the Department of Justice has been the most proactive agency in the government. A conservative with a history of racially insensitive remarks, Sessions let the president’s critique roll off his back while working diligently to dismantle Obama’s civil rights programs. A partial list of his accomplishments would include:

– filing court papers to undermine the rights of the LGBTQ community to be protected under civil rights laws;

– pledging to sue universities that pursue programs of affirmative action for black and Latino college students;

– blocking Obama’s moves to monitor police departments with records of bad relations with minority neighbourhoods;

– threatening to withhold federal grants from ‘sanctuary cities’ unless they comply with stricter immigration policies.

All this from an attorney general whom the president finds ‘very disappointing’.

Not far behind Sessions is Scott Pruitt, the head of the Environmental Protection Agency. Though Pruitt has been accused of spending too much time in his home state of Oklahoma, in the past six months he has:

– ignored most of the career professionals in the EPA and worked closely with fossil-fuel corporations like Exxon and Koch Industries;

– blocked or eliminated 30 different environmental safety regulations, including constraints on air and water pollution and requirements on energy companies to monitor the release of methane and ozone gas into the atmosphere;

– actively participated in the government’s exit from the Paris climate agreement;

– reversed a government ban on chlorpyrifos, a pesticide that EPA scientists concluded causes developmental damage in children.

Though the Trump administration has been lax in hiring middle-level managers for executive agencies and appointing ambassadors to foreign countries, they’ve aggressively pursued the nomination of conservative federal judges, especially in states that are part of the president’s camp. Their crowning achievement was the April appointment of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, who has proved to be the most aggressive first-term justice in decades. In the course of a few months, Gorsuch handed down rigidly conservative opinions on a variety of subjects that included the travel ban, gun rights, political fund-raising, separation of church and state, and same-sex marriage. In June alone he wrote more opinions than Elena Kagan, the next most junior justice, offered in her first two terms on the court.

This is hardly a comic presidency. If one looks past the comedy, one sees an administration that has moved the country day by day systematically to the right.

One issue has dogged the Trump presidency from the beginning— call it the Problem That Won’t Go Away. After six months, though both the domestic and foreign media have revelled in the daily gossip and innuendo about Trump’s Russian connections – and even with the 3 August announcement that Special Counsel Robert Mueller has empanelled a grand jury to hear testimony – no one has come up yet with the fabled smoking gun.

An article entitled ‘Trump’s Russian Laundromat’ that appeared in the July 13 New Republic approached the issue from a slightly different angle, and is worth taking a few moments to examine.

According to reporter Craig Unger, Trump’s involvement with the Russians hasn’t been so much a question of espionage and high-level intrigue as it has about real estate. Trump has been involved with Russian oligarchs since the 1980s; the first of his many all-expenses-paid trips to Russia took place in 1987. For decades, Russian money has flowed into Trump’s luxury developments and Atlantic City casinos: at least 65 units in Trump Tower were sold to Russians, and 63 Russian buyers put down $98 million on Trump properties in South Florida. In 2013, New York City police raided Trump Tower, where they broke up two gambling rings, one of which had laundered $100 million of Russian money. While there’s no proof that the president had any knowledge of the gambling rings or the money-laundering operation, in 30 years of deal-making with the Russians it stretches credulity to believe that he didn’t know whom he was dealing with.

As Unger puts it:

‘It’s entirely possible that Trump was never more than a convenient patsy for Russian oligarchs and mobsters, with his casinos and condos providing easy pass-throughs for their illicit riches. At the very least, with his constant need for new infusions of cash and his well-documented troubles with creditors, Trump made an easy “mark” for anyone looking to launder money. But whatever his knowledge about the source of his wealth, the public record makes it clear that Trump built his business empire in no small part with a lot of dirty money from a lot of dirty Russians…’

What are we to make of all this? If nothing else, it suggests that the Russian connection will haunt the Trump presidency for the foreseeable future, and probably a lot longer. So far, the president in his own peculiar way has been fairly resilient; he’s been careful to cultivate and remain connected to the ultra-conservative base that elected him. But if there’s anything that will bring him down, it will be the same hustling and deal-making that brought him to where he is now.

One is reminded of a vague but portentous line from Suetonius: ‘At last, after nearly fourteen years of Nero’s misrule, the earth rid herself of him.’

For a good portion of the American public, fourteen years – or even four – seems like an awfully long time to wait.