During the aggressive debate pro and con the cartoons in Jyllands-Posten and now the caricatures in French Charlie Hebdo, the opponents intensively search for arguments which might legitimize their spontaneous dislike of the publication of the cartoons, arguments to counterweigh the free speech proclamations which they, at the same time, feel obliged to make. One heard, for instance, that the decisive criminal aspect was that the cartoons in Jyllands-Posten had been published in a center-right newspaper; if the very same cartoons had appeared in a leftwing paper, they might have been alright. Now Charlie Hebdo is in fact a libertarian left wing magazine, and now the major argument against it is that it has targeted a minority group or its religious tenets. And this is supposedly not what free speech is all about. It was meant to be used against “those in power” and should not be used against minorities.

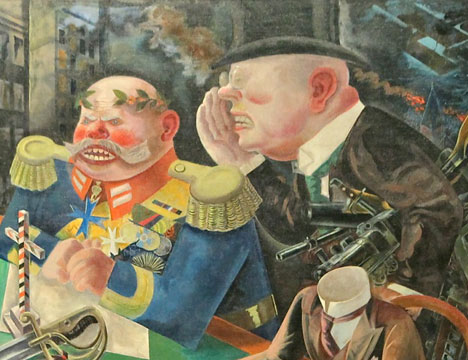

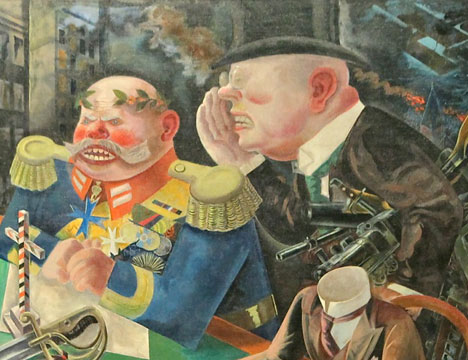

George Grosz, The Eclipse of the Sun, 1926 (detail). Photo: La Veu del País Valencià. Source: Flickr

Let us investigate this argument. Legally understood, no such thing is implied by freedom of expression. It is not claimed by the First Amendment of the American Constitution or by Article 77 of the Danish Constitution that free speech is a right only admitted to people criticizing powerful groups or persons, while state censorship in all other cases may be freely undertaken. The first part of the argument seems to rest on the idea that the primary motivation of freedom of expression is to direct the attention of the public to cases of abuse of power. This is, indeed, a very important function in public debate. The argument, however, rests on the further premise that it is evident for everybody to see who “the powers that be” are. The idea seems to be that “those in power” are easy to identify: they wear top hats, smoke cigars, expensive suits, drive fine cars and populate large downtown offices and look, by and large, like George Grosz’s cartoons of capitalists in the 1920s. But the problem in this populist idea is that, in a pluralist democracy, it might, in many cases, not be so easy to establish who “those in power” are and who abuse the powers with which they have been entrusted. This can only be established as a part of ongoing public debate. Is Jyllands-Posten a mighty power or is it, rather, a small paper in the crisis-ridden Danish press? Was Charlie Hebdo a powerful magazine with a circulation of 100,000 copies before the editorial staff were gunned down? Were the imams protesting against Jyllands-Posten powerless immigrants or were they members of a powerful international network? The power of persons and institutions may change dramatically from case to case, from context to context, and the powerful very often have an obvious interest in posing as powerless victims calling for support.

The reality of such issues may, in many cases, only be established in the course of continuous public investigation and debate, and to deny “the powerful” the possibility of expressing and defending themselves beforehand is not only contrary to free speech, but is also contrary to the basic juridical and journalistic intuition that an accused has a right to defend himself. It is therefore impossible to be sure that your expression is, in fact, aimed against the majority or only against “the powerful”, for it is only public debate which can ultimately determine who, in a given case, is powerful. A further premise for this sentimental argument is that minorities, eo ipso, are not powerful. But persons from cultural minorities in powerful positions may easily exert a brutal power over and against their own members, just as they may get the idea of abusing multiculturalist policies to support such a display of power or attack other groups. There are thus power rela-tions everywhere in a democratic society, from the smallest to the largest groups, and there is no position in society that is a priori secured against the illegitimate use of power.

Opponents of the Muhammad cartoons often vacillate between saying that a minority must not be mocked and saying that you should not attack a world religion with 1.3 billion believers, claims which entail a certain tension. Is the Danish Islamic Society of Faith a weak organization of a few Danish Muslims, or is it a part of a widespread, strong international network of Muslim Brothers with supporters in many countries? In a certain sense it is both of these things at the same time, and it was the strength of French filmaker Muhamed Sifaoui’s documentary that proved this to be the case: it showed that the allegedly small and purely Danish organization was a part of the international Salafist network. This documentary, which revealed and even ridiculed a Danish minority organization, should – according to the multiculturalist power argument – have been abandoned and not shown on television.

The argument that tenets held by a minority should apriori receive protection is strange because, in democratic societies, the vast majority of organizations and groups are, in fact, natural minorities. A minority of Denmark’s population support the Danish Labour Party, the leading force in the current government coalition (in recent years, the party received around 24 per cent of the popular vote). Does that imply that there is no right to criticize it? Should there be a limit imposed on criticism of the government as a whole, which has, by definition, a majority of voters behind it? Or is it illegitimate to attack the numerous religious minority groups in the West, such as Born Again Christians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Scientologists? Or to take another example: was it illegitimate, in 1920s Germany to attack a growing Nazi Party that was still a minority? Should one have postponed criticism of that movement until it finally assumed power in 1933 and became “powerful?”

It is probable that some of the proponents of the argument that it is in bad taste to attack Islamist extremist groups would mean something like this: we must not attack Islamists in the West, for they have no power; we must wait until they might assume power. At bottom, the argument is, of course, motivated by multiculturalism: all cultural groups are worthy of respect. They have a right to protection as “cultures”. Free speech may be used to attack the government only, because it is the only group in a democracy which eo ipso represents a majority. This is in fact the democratic contradiction of multiculturalism.