With a death toll long surpassing 30,000, the displacement of 1.4 million people, and a famine induced on a population already bearing the brunt of a 16-year blockade, Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza has been unparalleled in its levels of violence and destruction.

Also unparalleled has been the extent of the international outpouring of public anger at what the International Court of Justice has called a ‘plausible’ case of genocide. From Jordan and Egypt to university campuses in the US and Europe, publics in the Middle East and around the world have decried the devastation and havoc wrought on ordinary Palestinians, and have denounced the complicity of their governments in Israel’s war.

In the cultural and political regional sub-system that is the Arab world, every country has its ‘Palestine story’. Common historical and geopolitical experiences and memories of people subdued by colonialism render identification with Palestinians logical. But the Palestinian cause has also been used and abused for decades by dictators in the postcolonial Arab states, becoming a fixture of official discourse and school curricula.

The Tunisians have been at the forefront of demonstrations of pro-Palestinian solidarity in the Arab region. Like other Arabs, Tunisians consider Palestinians their brethren and sympathise deeply with their struggle for national self-determination.

From below, Tunisians have a history of armed resistance against Israeli occupation since 1948, involving Tunisian militants or fedayeen in the 1970s and onwards (described by Jean Genet in his late work Prisoner of Love). From above, however, Tunisia’s policy on Palestine has often been out of step with the rest of the Arab World.

Historical legacies

This goes above all for the gradualist position on decolonizing Palestine taken by Habib Bourguiba, the country’s first president (1957–1987). In his (in)famous March 1965 speech in Jericho, Bourguiba made a case for ‘provisional solutions’ as an alternative to purely emotive stand-taking, which he argued would ‘condemn us [Arabs] to live for centuries in the same status’ – which in the case of the Palestinians meant colonial occupation. The Tunisian president preferred avoiding Arab state-level confrontations with Israel and, above all else, was initially in favour of UN-drawn ‘partition’ borders.

The speech was not well-received by fellow Arabs, including Egyptian President Jamal Abdel Nasser, who deemed it too moderate. In hindsight, however, Bourguiba’s stage-managed approach to Palestinian liberation looks quite like what, since the 1990s, has been called the ‘two-state solution’.

After Egypt performed a volte face and made peace with Israel through the 1978–9 US-brokered Camp David peace treaty, the Arab League suspended its membership and moved the organization’s headquarters to Tunis. In an act of support for the Palestinian resistance, Tunisia also hosted the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), headed by Yasser Arafat, after it was expelled from Lebanon in 1982.

An Israeli air raid on Hammam al-Shatt, a suburb of Tunis, in October 1985 killed at least 50 Palestinians (narrowly missing Arafat himself) and 18 Tunisians, provoking public protests. Three years later, the Mossad assassinated Khalil Al-Wazir (known by his nom de guerre, Abu Jihad), the architect of the first Palestinian intifada, at his home in Sidi Bousaid. The two events are etched into the collective memory of Tunisians as a direct assault on their country’s sovereignty as well as on the Palestinian resistance. The attacks helped form additional bonds of shared struggle against Israel.

These snapshots from Tunisia’s history are significant. They show that, while Tunisia is not relevant to the Palestinian question in the same way as Egypt or Syria, which border on Israel and have waged war directly with their neighbour, Palestine has always been central to the Tunisian imaginary. This is important to point out, not just because to do so recalls Tunisia’s place in the complexities of a Middle East conflict born of European colonialism, which in Israel transformed into a new form of settler-colonialism, occupation and serial war-making, but also to shed light on the solidarity evident in Tunisia throughout the current war.

Tunisian solidarity with ‘free Palestine’

For close observers of the North African country, Tunisians’ outrage at Israel’s war on Gaza, and at America’s and Europe’s full-blown support for it, is no surprise. Popular solidarity (tadamun) is visible not just in street demonstrations, but also in everyday symbolism, from the ubiquitous Palestinian flag to the keffiyeh worn by public figures and media personalities. In Tunisia, pro-Palestine mobilization or hirak spans both society and the state, the civic and the political.

Despite pertaining to an international political crisis, the public outcries inevitably have domestic political significance. Support for Palestine has become the most sustained expression of bottom-up political dissent since the 2011 revolution that ousted the longstanding dictator Ben Ali. Such a phenomenon has implications for a country experiencing a dramatic (and disheartening) process of democratic backsliding since July 2021.

Pro-Palestine mobilization in Tunisia is stratified, emerging among different socio-political groupings within society. Parsing these stratifications enables us to draw a comprehensive picture of public opinion in the country.

Football ultras and youth

First is the youth cohort not affiliated with trade unions, student syndicalism, political parties or organized civil society. Tunisia’s youth are a good barometer of where current and future public opinion stands, since their position derives neither from ideology nor political calculus.

Among the first manifestations of youth solidarity with Palestine since 7 October 2023 were performances by football fans. Ultras in particular claim distance from politics, but not where Palestine is concerned. At a Club Africain match in late October 2023, ultras choreographed a tifo spectacle backing the Palestinian resistance. It was among the first of its kind in the Arab region and was echoed by ultras in Morocco, Egypt, Algeria and elsewhere. The atmosphere was characteristically festive. Nationalist Palestinian songs blared in the background, fans and spectators clapped and chanted, and countless Palestinian flags fluttered in the stands. A huge black-and-white banner read, in English: ‘We Stand with Palestine: Resistance Until Victory’.

Weeks later, after the grinding violence had taken its ghastly toll on the lives of thousands of Palestinians, Club Africain ultras waved a banner honouring the 6405 children killed by Israel until that point. In a country where youth are increasingly depoliticized, this expression of sympathy among football fans underscores how much of a ‘no-brainer’ support for Palestine is in Tunisia.

Syndicalist organisations

Tunisian syndicalists in both their trade union and student iterations have historically aligned themselves with the Palestinian cause. This time is no different. The Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), the country’s largest trade union, has led the mobilization and organization of solidarity protests. With its enormous national constituency and well-oiled organizational machinery, the UGTT has long been well-placed to spearhead protest coordination.

A statement published on the Union’s Facebook page on 10 October 2023 from the UGTT Secretary General, Noureddine Tabboubi, set the tone. Tabboubi called on members to ‘support our Arab people in Palestine against brutal Zionist aggression’ by participating in a 12 October protest march taking off from the UGTT headquarters in Belvedere to the centre of Tunis. Confirming how un-controversial support for the Palestinian resistance is across the spectrum of often ideologized civil society, Tabboubi signed his statement, ‘glory to the resistance and eternity for our people’s martyrs’.

Note here the tone of collective ownership of the Palestinian cause. Moving quickly and adeptly, the UGTT has been the most prominent head of the National Committee for Supporting the Resistance in Palestine. The Committee includes a number of partisan and civic forces, among them leftist and pan-Arab parties (WATAD and El Chaab), the National Order of Tunisian Lawyers, the Tunisian League for Human Rights, the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights, and the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women.

In and outside the National Committee, the UGTT has effectively drawn on its rank-and-file members across sectors and regions to participate in solidarity activities for Palestine, including protests as well as fundraising for humanitarian assistance to Gaza (members were encouraged to donate the equivalent of a day’s pay). The UGTT has also held cultural activities with such titles as ‘Palestine is our Cause’ on 10 November 2023. These events are occasions for political engagement and socialization of members and the broader public into the Union’s involvement in what has been the region’s most prominent political issue and conflict for decades.

On 15 January 2024, the UGTT received Hamas officials in Tunis to discuss ‘the union’s willingness alongside its partners to engage in humanitarian initiatives in support of the Palestinian people to mitigate their suffering and [the effects of] the attacks they face by the Zionist enemy’. The UGTT, as a trade union belonging to the Global South, views Hamas in the context of the struggle for decolonization and liberation. The legacy of anti-colonial history remains strong. Next door, the French were defeated in a bloody guerilla war without which Algeria would not have won independence in 1962. It was these very same French colonisers who murdered one of the UGTT’s founding fathers, Farhat Hached, in 1952. In sympathising with Hamas, Tunisia’s powerful left-leaning union is aligning its own position with that of its rank-and-file.

Along with other political forces in Tunisia, the UGTT sees western democracies’ rejection of violence on the part of the Palestinian resistance as simplistic. As part of the civil society ‘Nobel Quartet’ of 2015, the UGTT’s democratic credentials were proven during the processes of institution-building and dialogue leading to the adoption of the 2014 constitution. But for the UGTT, western support for Israel in the first months of the war has eroded the European stance on democratic norms and human rights.

Students

Student syndicalism has also had a strong presence in Tunisia’s hirak for Palestine over the past nine months. Tunisia’s student movement has traditionally mirrored the organizational structure and mobilizational capacity of the UGTT within the university, with the General Union of Tunisian Students (UGET) and the Tunisian General Union of Students (UGTE) framing student activism, as they have done on numerous previous occasions throughout Tunisia’s postcolonial history.

In early May 2024, journalism students at the University of Manouba’s Institute of Press and Information Sciences (IPSI) set up what they dubbed Shireen Abu Akleh Camp, named after the Aljazeera journalist gunned down by Israeli forces while reporting in Jenin in 2022. Not unlike American students’ demand that their universities divest from companies linked to Israel, IPSI students insisted that the institution sever its ties to the German Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung for its pro-Israel statements in October 2023. But unlike their US counterparts, their position was compatible with that of decision-makers, policy elites and administrators, and the Manouba students managed to convince the ISPI leadership to end its relationship with the German foundation.

This episode illustrates not just Tunisians’ solidarity with Palestinians, but also their defiance of foreign governments seen to be enabling Israeli what Tunisians – like many Arabs – consider the genocide (ibadah) in Gaza. At the Tunisia Bookfair in late April, for example, attendees protested at the participation of the Italian ambassador, chanting ‘Italy is Fascist!’ and ‘Freedom for Palestine’, until the ambassador was escorted out. The National Committee of Support for the Resistance in Palestine has also called for the expulsion of the American and French ambassadors.

Feminists and women’s rights activists

Part of the civil society panoply in Tunisia are feminist and women’s organizations, which have joined coalition-coordinated protest for Palestine. They have condemned Israel’s war on Gaza from the perspective of ’women’s experiences and sought to give voice to their solidarity in creative ways. On 25 November women also organized a silent ’protest they called ‘Place your heart on my heart, my mother (dear)’. The name came from the words uttered by a grief-stricken mother in Gaza who, upon encountering her slain daughter, was adamant that she hold her child one last time. The protest march in the capital was meant to exhibit a ‘funereal silence’, according to one of the organizers; women, she said, felt like they ‘wanted to scream’ but were helpless to stop the war.

During an event that was part of the UN’s ‘16 days of activism against gender-based violence’ in November 2023, the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women underscored the parallels between domestic and wartime violence – what feminist theorists call the continuum of violence. Like women elsewhere in the region and around the world, some women in Tunisia are victims of physical abuse at the hands of their husbands; but in Gaza, all women are currently subject to genocidal violence. A Palestinian feminist activist guest reiterated this message and applauded the fact that sister activists in Tunisia were better situated than those in some other countries in the region (perhaps with less vociferous civil societies) to propagate the message of solidarity.

On International Women’s Day 2024, the UGTT issued a statement stressing the humanitarian plight of Palestinian civilians. It began by decrying the plight of women and children in Palestine, who have comprised 70% of people killed by Israel in the raging conflict. The ‘credibility’ of international agreements intended to protect vulnerable women and children were questionable, the statement declared, going on to say that the failure of states and governments who self-identify as standard-bearers of human rights to protect Palestinian women and children had caused a ‘moral crisis’.

For feminists and women’s rights activists, as this statement implies, the brutal war in Gaza is an affront not just to human rights norms in general, but to the rights of women and children in particular; Israel, they argue, has inflicted gendered harm on an entire society. Now that gender equality and women’s empowerment have become global markers of respect for human rights and overall wellbeing, the West’s refusal to even acknowledge, let alone eliminate this harm renders much of its human rights discourse problematic, so Tunisian feminists claim.

Media and culture

Protest and public statements are not the only measures of Tunisian attitudes to Palestine. Media and cultural articulations of solidarity have emanated from both state and society. After 7 October, Tunisian radio, television, print and internet platforms were inundated by news reports, opinions and analysis, just like in most other countries in the region and indeed the world.

Nine months later, the coverage is no longer wholly focused on Gaza. But from the semi-official Al-Watania TV to privately owned radio like Mosaique FM and the print and online Assabah, stories on Gaza and the West Bank, the International Court of Justice, the Biden administration and other regional and international developments still run very frequently. The overall tenor is decidedly pro-Palestinian.

Cultural output has also been notable. Soon after the violence broke out, the Ministry of Culture hosted a concert ‘in solidarity with the Palestinian people’. Belting out songs from Palestinian folklore, the event included performances by Jordanian singer Macadi Nahhas and Tunisia’s own Lotfi Bouchnak, alongside the Tunisian Symphony Orchestra. Proceeds went to Gaza through the Tunisian Red Crescent.

In a recently released song dedicated to Palestine and titled ‘O My Nation’ (Wa Ummatah), Bouchnak laments the ‘mirage’ of western human rights, which enable bloodshed against Palestinians and the Arab people. He does not mince his lyrics, directing his poetic and musical ire more against the West than Israel: ‘And the West grants to the occupier a cannon/So that it kills children and women.’ Yet the song ends on a defiant note. ‘In the pulse of people remains a cause’ – the liberation of Palestine, which Bouchnak predicts will spur an Arab ‘renewal’.

Music taps into deep emotional investments in and affective responses to the quest for Palestinian emancipation – echoing, perhaps, Tunisians’ and other Arabs’ own search for freedom. Beyond expressing commiseration over shared catastrophes and anger over injustice, music can move individuals and groups to action.

In addition to protesting, some Tunisians have joined regional and global campaigns to boycott foreign companies who do business with Israel. (Reports suggest some American corporations active in the region, including McDonald’s and Starbucks, have started to feel the pinch.) Tunisian activists have also been urging the boycott of French supermarket chain Carrefour and American Coca Cola, among others, often through social media messaging. Artists have also taken political positions. Famous Tunisian actress Hend Sabri’s resigned from her UN World Food Program Goodwill Ambassador post in objection to ‘starvation’ in Gaza even before dire UN warnings of an ‘entirely man-made disaster’.

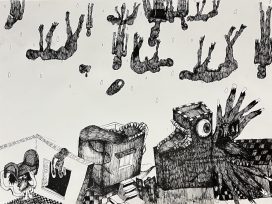

In an age of violence and dehumanization, abundant creativity is evident in a kind of ‘counterculture’. Here is where civil and artistic society excels. After the Culture Ministry cancelled the annual Carthage Film Festival, planned for late October 2023, in solidarity with the Palestinians, aesthetically and politically minded youth moved to curate ‘resistance cinema’. Films about Palestine were displayed on the walls of public spaces, including the French Institute, which had been covered over pro-Palestine graffiti soon after war broke out.

Palestine solidarity from below seems to have had the final word, disruptively making use of public space to disseminate art for the people, by the people. None of us have forgotten the very political graffiti surfacing at the time of the 2011 revolution. The call for Palestinians’ freedom deserve as much pride of place as the slogan ‘Tunisia is free’ over a decade ago.

Political and partisan actors

Palestine solidarity comes to the fore in the actions and words of various social actors, some organized, others less so. But ultimately, the violence in Israel-Palestine and relations with Israel’s allies are also necessarily the stuff of formal politics. The President, who fancies himself guarantor and embodiment of ‘true democracy’, therefore finds himself in a paradoxical position. While the state under Kais Saied limits basic freedoms, political pluralism and civil society, it goes out of its way to encourage protest and dissent on the issue of Palestine.

At least twenty opposition politicians, from Rachid Ghannouchi (leader of Islamist Ennahda) to Ghazi Chaouachi (Democratic Current) and Abir Moussi (Free Destour Party, Ennahda’s arch-rival) have been in detention since July 2021. Many of them remain in jail. Yet the President seems invested in Tunisian solidarity with Palestine, public demonstrations included. Saied and his supporters, like the El Chaab party, as well as his opponents, like the National Salvation Front (whose most substantial partisan component is Ennahda) are all clear on denouncing Israel’s war, issuing scathing criticism of western countries and declaring solidarity with Palestinians.

It may be that the Tunisian state under Saied is thereby camouflaging other sticky political problems like the Constitutional referendum of 2022 and the parliamentary elections of 2022–23, which most of the voting population either ignored or boycotted. The presidential elections this autumn, which are expected to favour an incumbent victory, will also be an occasion for criticism of Saied.

Yet despite Saied’s populist encouragement of pro-Palestine protest, one point must be made. At a time of low voter turnout, Tunisians mobilize for Palestine. This is a kind of ‘vote’ for a political cause that remains worthwhile for many and appears untouched by the general political malaise that has gripped the country over the past few years. The cry ‘free Palestine’ is the defining slogan of Tunisians’ solidarity, for which they require no permission or invitation to express, whether from the President or anyone else.

No normalization on the Tunisian horizon

After the democratic revolution in Tunisia in 2011, Palestine has consistently featured in the (re)construction of a national identity. The preamble to Tunisia’s (first and last) democratic constitution of 2014 pledges support for ‘all just liberation movements, at the forefront of which is the movement for the liberation of Palestine’.

The specific forms that such support should take has for years been fodder for debate in Tunisian foreign policy. The question of normalization with Israel has repeatedly arisen in response to developments at the regional and international levels. US President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in December 2017 was one such occasion. Then, the El Chaab party and the leftist Popular Front tried to resuscitate legislation that would criminalize normalization, after such a potential law had been rejected by the National Constituent Assembly (2011–2014). El Chaab and the Popular Front complained that the ruling coalition, made up of the now-defunct Nidaa Tounes (the party of then president Beji Caied Essebsi, who died in 2021) and Ennahda, had blocked the legislation.

For years, Ennahda has faced accusations that it let the problem of normalization slide when it held or shared power (2011–2021). The reason, according to critics? Protecting the party’s or Tunisia’s regional relations with some Arab states and, more importantly, with western states who bestowed financial and military largesse. Even if no anti-normalization law was passed under its rule, Ennahda has long denied allegations that it opposed such a political position. Some Ennahda members retort that Essebsi and his ministers even held up the bill back in 2017. Saied’s coup that froze and then dismissed Parliament in 2021 killed another opportunity to pass an anti-normalization that was on the table at the time, according to this narrative.

As a ‘dark horse’ candidate for the presidency in 2019, part of Kais Saied’s wide popular appeal was his declared clarity on the issue of Palestine. Normalization should be considered ‘high treason’ or khiyanah ‘uzma, he declared in the presidential debate with the media mogul Nabil Karoui. Saied’s opponent, already mired in corruption allegations, was seen as soft on Israel and accused of having ties to an Israeli lobbying firm. Saied thus literally made his name on standing up for Palestine and against the settler-colonial policies of Israel.

The language of the 2022 constitution went even further than that of 2014. All peoples ‘have the right to decide their own destiny’, the Preamble states, ‘the first of which is the right of the Palestinian people to their stolen land and the establishment of their state after its liberation, with its capital located in honourable Jerusalem’. Saied’s perceived backtracking in the wake of the Gaza war, when he blocked the anti-normalization bill being debated in the rubber-stamp parliament, was therefore sure to provoke public ire. However, protests have had so far little policy consequence, and Palestinians still face difficult visa requirements, despite the efforts of some MPs before July 2021.

Despite maintaining its opposition to Kais Saied’s coup, Ennahda is careful to insist that it has no qualms with the president’s position on Palestine, which seems generally in sync with public opinion. This did not prevent Ennahda members criticising Tunisia’s abstention in the first UN General Assembly resolution calling for a ceasefire, however. Whatever the reason for Ennahda’s past failure to oversee passage of an anti-normalization law that appears in line with public sentiment, Saied has himself not prioritized codifying prohibition of this legislation.

Tunisia’s public and political elites are crystal clear in their condemnation of Israel’s war in Gaza and their blame of western governments, which are seen as having enabled Netanyahu’s defiance of a ceasefire and criticism at home. Particularly since the 2020 Abraham Accords, debate in Tunisia is not about whether to normalize with Israel, but about how to guarantee an anti-normalization stance. Here ‘high state interests’ are at stake, with many speculating that international pressure to normalize has not skipped Tunisia.

But despite the increasingly likely prospect of Saudi Arabian normalization, Tunisia appears to remain firmly opposed. Even under Saied, the country’s high-level politics seem more in line with public opinion than in domestic matters, such as popular participation and representation in government, basic civic and political freedoms, political pluralism and alternation of power.

Prospects

The Palestinian cause is creating traction worldwide. University protests and the intense police crackdowns from Columbia to UCLA have seen to that. Solidarity with Palestine in Tunisia should therefore be seen within this broader global context. The debate over Israel’s actions and the role of western countries, especially the US, the UK and Germany, as participants in the gut-wrenching violence filmed and watched live across the world, is not confined to any one geography. It is everywhere. Perhaps for the first time in history, Palestine no longer seems to be just an ‘Arab’ or ‘Islamic’ issue, but a global cause drawing solidarity across geographies, cultures and political systems.

The American agenda for normalisation in the wake of Gaza faces uphill battles in countries like Tunisia. It will be very difficult for people to entertain the idea of establishing diplomatic ties with Israel, given the colossal destruction and precarity in the wake of the war. Palestinian statehood cannot but be a prerequisite for future normalization, whichever countries are willing to entertain it next. Tunisia is not at present poised to be one of them.

Finally, it may be an irony that conflict and war strengthen public mobilization or hirak. But what we have witnessed over the past nine months is reminiscent of the 2011 protests and revolutions. Might it be a ‘rehearsal’ of sorts for the next Arab Spring?

Here a note of caution is necessary. Since the beginning of the Israeli onslaught on Gaza, western governments have shown great hypocrisy when it comes to applying norms of popular sovereignty, international law and human rights. The West is now seen in the Arab world and beyond as being complicit in genocide. But because the Euro-American democracy agenda is so damaged, the war has strengthened authoritarianism in the Arab countries. Movements speaking out for democratic governance now have even greater difficulty getting through to Arab audiences.

There is thus a double weaponization of dissent. The voices of Arab peoples, including Tunisians, are raised against Israel, but also against the EU, the US and individual leaders (‘genocide Joe’). Simultaneously, Arab dictatorships have been strengthened in their course of democratic backsliding. If the West can be so hypocritical in its adherence and protection of basic human rights, people ask, then why not do away with the goal of democracy, too?

This is the mistake of policymakers from Biden and Blinken to Scholz and Macron. Western countries have had no small part to play in what UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese has called a ‘long-standing settler colonial process of erasure’ in Gaza, in flagrant violation of international law. That the public voices expressing solidarity with Palestine are democratic ones, inside and outside western countries, is yet another paradox.

The Arab world is already beginning to tilt towards China and Russia, the BRICS and the Global South generally. As always, the future of the region is uncertain. But the Palestinian cause is here to stay.