Another day, another denunciation of Dawkins and Hitchens and their fellow New Atheists. No sooner have we absorbed Chris Hedges’ I Don’t Believe in Atheists (2008), Tina Beattie’s The New Atheists: The Twilight of Reason and the War on Religion (2008) or David Bentley Hart’s Atheist Delusions (2009) when along comes God is Back: How the Revival of Religion is Changing the World, by Economist journalists John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge.

But this “God book” is of a rather different order. Unlike its rivals it contains a wealth of fact and subtle argument, empirical evidence and expert witness. As we might expect from The Economist its perspective is global – it sweeps comfortably from the corridors of the Pentagon to a front room church in Shanghai, and speaks authoritatively about events in Nigeria, Pakistan and Egypt. Altogether it lays down a very serious challenge to any of us who had waved God a not-so-fond farewell.

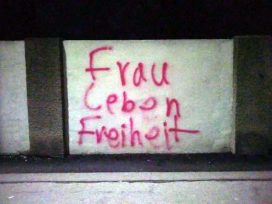

The challenge is threefold. First in line is the secularisation thesis, the argument that religion simply fades away as a natural consequence of modernisation. Not true, argue Micklethwait and Wooldridge. Modernity doesn’t usher in secularisation, it actively promotes religious pluralism. They then train their sights on the equally popular notion that religion contaminates all those who subscribe to its bogus myths and stories. Not true, argue Micklethwait and Wooldridge. Religion brings out both the best and worst in man, and secularists need to come to terms with the positive role religions have played in providing meaningful care and support for the oppressed as well as in the nurturing of aspirations for political freedom from Poland to Burma to El Salvador. Secularists should therefore recognise the corollary of these two facts. While it is perfectly appropriate to demand that religionists should accept the separation of church and mosque from state as a guarantee of freedom of conscience for all, secularists should play their part by accepting that religion is here to stay.

Consider the United States. It is both the most modern and one of the most religious countries in the world. It also provides solid evidence of how religions can provide a commendable array of social services in the absence of an effective welfare state. But it is also a perfect example of how religion can be kept separate from the state. If we could all become more like America, the book argues, we could all get along famously.

I met up with John Micklethwait in a spacious office on the 13th floor of the tallest building in West London’s Economist Plaza. He sipped from a can of Coke as he apologised in a friendly, youthful manner for the mess on his very noticeably tidy antique desk. I began by pressing him on his objections to the well-known secularisation thesis. Were he and his co-author really saying that Durkheim, Weber, Marx, Freud and generations of sociologists had got it wrong?

“Well, I’m not sure we are the first people to say it – after all the distinguished sociologist Peter Berger changed his mind about it a while ago, which was a pretty seismic event, and sociologists have been arguing about it ever since. The difference is that as reporters we have gone out into the world and seen the evidence. We have seen that religion is not going away, that it is in many ways a partner with modernity and not in conflict with it. Many people in Europe, ourselves included, missed the signs that religion was coming back. It took 9/11 for us to take notice, but as a phenomenon it started well before. Even as a Catholic I grew up in an environment which completely accepted the notion that modernity and religion are incompatible – we all thought that if religion did survive it would be a kind of subtle Anglicanism, some version of a doubting Graham Greeneish religion. The evidence shows we were wrong.”

And, he went on to claim, it wasn’t only the classical academics who’d got it wrong. The political class, across the West, was almost wilfully blind to the return of the sacred. “Take the CIA looking at the Shah of Iran, just before the revolution. Someone wrote a report saying that religion was an important factor in what might happen, and someone else scribbled a dismissive note on it that it was ‘mere sociology’. Or when Hezbollah first appeared in Lebanon and people were trying to fit them into the old left-right spectrum – I mean this was a group calling itself ‘the party of God’. When the Americans were preparing to invade Iraq it was clear that no one in the State Department knew anything about the differences between Shia and Sunni – they just didn’t think it mattered. In Europe there was this same pattern. Immigrants from all over the world moved to the UK and set up organisations like the Muslim Council of Britain, and the secular British state kept trying to reinterpret them as national or ethnic groups – they didn’t understand the significance of religious identity at all. History does not record the dwindling importance of religion. Instead it’s a story of people trying to push the issue aside – until September 11.”

There was also the compelling evidence of the emergence of new forms of Christianity in China and Nigeria, the growth of Islam across the Arab world and in Asia, and the proliferation of different strands of belief in the USA. And all of this was happening while modernisation proceeded apace.

At this point we were “joined” by Micklethwait’s co-author Adrian Wooldridge, on the phone from Washington. His voice emerged, loud and clear and disconcertingly, from a golf-ball-shaped speaker in the ceiling. (It crossed my mind that it was not unlike interviewing the Archbishop of Canterbury and having God join the conversation.)

Wooldridge took up the question of what we can learn from American religious pluralism: “European secularists assume that the church is on the side of the ancien regime, of the establishment, that it’s against reason and democracy and liberal emancipation, and there is a lot of evidence for that in Europe. But in America the evangelical movement advanced alongside democracy and liberal enlightened values. They were not oppositional forces but comrades in arms. If you give people more freedom and more democracy they will talk about what they want to talk about and obviously for many people that is God. Religion itself has also been important for advancing democracy – it’s an example of the little platoons of civil society. Churches nurture certain civic values, that’s why the Chinese government, and all totalitarian governments, have been very suspicious of them and have tried to crush them.”

Micklethwait was quick to provide reinforcement. “In Eastern Europe religion has served as a battering ram for opening up the post-communist world because it serves as a focus for discontent. In Poland or Latin America even the Catholic Church has been a focus for dissent. The church can act as a barrier to democratisation, as the Catholic Church did for a long time in Europe, but it can also inspire democratisation.”

They are only too happy to concede that religion has been and still can be a disaster. What they resist is a simple dichotomy. Wooldridge put it like this: “The problem with this subject, and I speak as a Balliol atheist here, is that people want to see a neat antithesis between liberalism and religion, or modernity and religion, or reason and religion, and it just doesn’t work. Religion has a good side and a bad side. Sometimes they can come together in the same organisation, as with Hezbollah. It’s complicated.”

I wondered if they realised the alarm with which rationalists and atheists would greet their suggestions that as democracy increases around the world we should expect to see the emergence of more “parties of God”. Did they recognise that this was a kind of nightmare for many of us? “If the parties of God are Hezbollah then they are nightmares for us too,” says Micklethwait. “The thing is, when democracy is concerned the secular-minded always think that people will go off and vote for ‘normal guys’ but of course they don’t. It’s not just the most oppressed who do this – in India and Turkey the educated bourgeoisie, exactly the people who should be the most secular, the driving force of the economy, have flooded towards religiously inspired parties.”

This is not necessarily a welcome development for either Micklethwait or Wooldridge. They are pragmatists. Religion is there, and you have to deal with it.

But didn’t their pragmatism wear a little thin when they turned in their book to the manner in which religion did good? In their portrait, for example, of the many ways in which American Christianity provided vital welfare to the needy, an expertise they dub “soulcraft”. Not so, argued Adrian Wooldridge. “If you look at the world of social services, religion provides two things very well. One is you have people who are willing to make sacrifices and do things that it is hard to believe that secular-minded people would do. People like Pastor Richard Smith from the Faith Assembly of God in Philadelphia, who would just walk into crack houses where people were pointing guns at him and try and close them down. No rational person, let alone any social services bureaucrat, would do that sort of thing. He was absolutely convinced that God would protect him. He devoted his entire time to helping the poor, the homeless, drug-addicted people, with very few resources. His story is remarkable but I think it is multiplied in a lot of different places. If you took away the work that is done by the church in Philadelphia alone it would represent about half a billion dollars of social services cost a year.”

But wasn’t there some traditional Economist bias against the welfare state here? Weren’t the churches in the US merely compensating for the fact that US welfare is so threadbare? Wouldn’t it be preferable if such care was provided by the state and not delivered in the context of faith? Wooldridge, the atheist, was having none of that. “Care is actually better if it is provided in a faith context. If you look at social services you have to fill in forms, people are antagonistic or they do it because they have to, whereas if you go to church for help you know you are talking to another human being who actually cares. Its not just in the US – the same is true in China or Russia and part of the Middle East. If you look around the world you have weak welfare states that don’t provide, and it is unlikely that they will provide in the future. Most people who become welfare-dependent do so because of lack of skills, lack of opportunities, but also because of a lack of self-worth or a lack of a sense of meaning or purpose. These are things that religion is very good at, that bureaucratic welfare systems can’t do. So yes, I think they are a good in themselves.”

Though the tone at times tends toward the celebratory, the authors recognise the catastrophic damage religion can do too. “We disagree with European secularists in the idea that God is dead or unimportant, or that modernity and religion are incompatible,” says Wooldridge. “Where we strongly agree with them is with the idea that religion can be dangerous, and we think that this happens when you get a fusion between political power and religion”. And they think they’ve found the solution. “The lesson other countries should learn from America,” Wooldridge continues, “is that the separation between church and state is the basis for a flourishing civil society.”

Just as American entrepreneurial can-do provides the model for the Economist-approved form of global capitalism, so religion American-style is the exportable model for faith. “We think internally America has the best system for dealing with the return of religion,” insisted Micklethwait. “If only they could recognise it, and model their foreign policy on it. They have plurality of religion, which does not clash with progress, and if people are going to continue believing in God, which they are, then some kind of formal separation between religion and the state seems a really good idea. With the constitution America has that bit cracked.”

But did we really want more exporting of American models to the world? Wouldn’t we end up with more megachurchs and McMosques, with the emergence of powerful consolidated global religious brands? “There may be a degree of consolidation, but the thing about American religions is they come and go. The Methodists swept through everything, then the Baptists were in the ascendant, then the Catholics come back a bit. Nobody ever quite hangs on to dominance. It’s a vigorous, competitive marketplace of ideas.”

This might well be true of America. But when, I asked, might we expect to see a free market of religions in Saudi Arabia? Micklethwait happily conceded that Islam has a good deal further to travel but pointed out that it is losing significant ground to Christianity in the new markets of Asia and Latin America. “This is not what we expected given how well Islam did compared with Christianity in the 20th century in terms of expansion, and given that it was the arrival of Jihadi violence that alerted the world to the return of religion. Islam’s problems with plurality and individual conscience will drag it back. It has to go through a process – a Reformation or Renaissance or Enlightenment – which will be painful. It’s entirely possible that Islam will go through some horrific revolutions. Equally what might happen is that Muslims who live in the West, those with experience of living in a plural society, might start to change Islam from within. Saudi Arabia does not look like a likely candidate to offer a modernised Islam.”

It is because of their (very Economist) emphasis on the benefits of religion as a kind of spiritual marketplace, with traders free to set up stall, consumers free to choose, and rules against monopoly, that the authors choose to end their argument with a clarion call for global disestablishment, and a more local demand for the ending of the established church in Britain. “Rowan Williams is a decent man but there is no way you can defend the situation where we are the only country other than Iran to have clerics at the heart of our political system,” says Micklethwait. “Disestablishment would also be a very good thing for the church – it would allow them speak more clearly and compete in the marketplace of ideas. Has the Church of England gained from the past 200 years of being an organ of the state? I think not.”

I left feeling in need of more proof that the secularisation thesis was completely wrong: experience seems to suggest that rising educational standards do reduce religious affiliation. But I felt more able to acknowledge that the process is far from even and that globalisation is throwing up more diversity of belief. Nor did I feel ready to accept that faith-based social welfare is the best model for developing countries, but then perhaps I am romantic about the NHS.

We should all be cheered, however, by Micklethwait and Wooldridge’s unconditional support for disestablishment – they will make useful allies in keeping up the pressure on theocracies worldwide, as well as launching the long overdue expulsion of the bishops from the second chamber here at home.

Secularists might find some of the arguments in this book hard to swallow, though they should welcome the opportunity to sharpen their own against them, but as a clear and convincing case for the separation of religion and politics, it counts as a considerable, and unapologetically secular, achievement.