Forwards and forever forgotten

- Eurozine Review

9/2017

‘Osteuropa’ describes the uses and abuses of 1917; ‘LaPunkt’ prefers Burke; ‘Ord&Bild’ goes in search of lost time; ‘Wespennest suffers the anxiety of inheritance; ‘Mittelweg 36’ historicizes anti-academicism; ‘New Eastern Europe’ looks even further east; ‘Esprit’ welcomes suburban meritocracy; and ‘Symbol’ speaks to a connoisseur of French Theory.

Osteuropa (Germany) 6-8/2017

What is the political meaning of Russia’s official commemoration of 1917? In an insightful introduction to the new issue of Osteuropa, entitled: ‘Revolution Redux. 1917–2017: Forwards and forever forgotten’, editors Volker Weichsel and Manfred Sapper write that ‘Russian memory politics represses both the utopia and the violence. It wants neither to know about the perpetrators nor to commemorate the victims. It recognizes only one tragedy, which allegedly struck society like a natural disaster – and the state, which alone was able to offer salvation.’ The editorial can be read in Eurozine in English translation.

A fading memory: ‘The history of Soviet and post-Soviet revolutionary anniversaries may be broadly thought of as a cardiogram capturing the gradual fading of the revolutionary heartbeat,’ writes Ilya Kalinin in an article on the commemoration of 1917 in Russia today (a shorter English version appeared in the TLS on 17 February). ‘It is difficult, Kalinin writes, ‘to imagine anything further from communist ideas and socialist values than the modern Russian state.’

‘The overarching goal of the rulers’ patriotic propaganda consists in hiding from society, and indeed from themselves, the fact that the maxims that inform the everyday praxis of almost all sections of the population, throughout the entire social pyramid, fit neatly into the picture of the globalized world which is officially associated with image of the decadent West. Consumerism, competition for the good things in life, and individualism are much more in demand than Russian Orthodoxy, love for the Fatherland and a collective sense of national unity. The mythologizing of the past, the construction of a heroic national tradition, have therefore become almost the only ways to fill the inner emptiness of the national patriotic idea.’

The original Maidan: In Russia, ‘the October Revolution appears as the original Maidan’ writes Tatiana Zhurzhenko: ‘a German conspiracy aimed at destabilizing the Russian state’. In Ukraine, in contrast, ‘revolution has become fashionable’. The October Revolution possesses ‘residual charm and still symbolizes an alternative to post-Soviet capitalism’. In official commemorative politics, on the other hand, ‘the Maidan is a continuation of the Ukrainian revolution of 1917–21 which was defeated by Bolshevik Russia. This view fits in seamlessly with the official politics of de-communization that began in 2015.’

Also: Kristiane Janeke on how the exhibitions about the Revolution being held in Russia this year reflect uncertainties in official history policy; Zaal Andronikashvili on the repression of the fact that, in Georgia, the 1917 revolution was led by the Mensheviks; and Nikolai Plotnikov on the roots of the view of 1917 as a ‘time of troubles’, which also shapes the official view of the 1990s.

More articles from Osteuropa in Eurozine; Osteuropa’s website

LaPunkt (Romania)

In Romanian online journal LaPunkt, founding editor Ioan Stanomir writes that ‘utopian radicalism’ is far from being a footnote of history, but is instead very much a feature of our times. ‘Collectivism’, argues Stanomir, is the main malady of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, under its various manifestations: fascism and Soviet communism, anti-capitalism, anti-Americanism and vestigial anti-Semitism.

For Stanomir, Edmund Burke’s denouncement of revolution and defence of moderate politics is as relevant as ever. ‘Now, more than ever, a certain humane modesty of governing goals is what can discourage the inclination towards paternalism and collectivism, equalitarianism and state omnipotence,’ he writes.

Romanian unification: Next year, Romania celebrates 100 years since its 1918 unification. LaPunkt predicts a mediocre display of self-congratulatory nationalist rhetoric, in the style of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s ‘national Stalinism’.

Instead of glorifying a Romanian nation that miraculously came together, writes Stanomir, it might be better to see the events of 1918 as part of wider regional dynamics, most notably the simultaneous weakening of both the Russian and Habsburg Empires – a factor highlighted by Romanian historian Lucian Boia. Peace will be better served by accepting different readings of the history of a place, and seeing it has having belonged to different communities, instead of insisting on a single national history.

Textbook politics: LaPunkt gives ample space to a debate over plans for a return to standard school textbooks (Romanian schools can currently choose from several). Teacher Florina Rogalski, an author of textbooks herself, is quoted as saying that, ‘The proposed measures [to reintroduce a single textbook] signal a return to statism, make the act of teaching uniform, and are an abuse of and an attack on democracy’.

If you ask me… In Journal of a Taxi Driver, a former journalist muses on daily life spent in Bucharest traffic.

More articles from LaPunkt in Eurozine; LaPunkt’s website

Ord&Bild (Sweden) 4/2017

To mark its 125th anniversary, Ord&Bild remembers time passed with reflections on different decades. Two contributions come from Ord&Bild’s rich archive. The 1910s is represented by Lydia Wahlström, who published an essay on the Swedish women’s movement in 1911. At the time, she was the chair of the Federation for Women’s suffrage; the vote wasn’t extended to women until almost a decade later. Half a century later, a poem by Sylvia Plath first published in Ord&Bild in 1963, shortly after her death, marks the 1960s.

Autobiography: The autobiographical turn is visible throughout the issue. Novelist and former Ord&Bild editor Agneta Pleijel offers a highly personal view of the 1950s, placing her own coming of age alongside international events such as the Suez crisis. And Ann-Marie Tung Hermelin returns to the international milieu of 1970s Stockholm in which she grew up. Her father, a Chinese-American political scientist, was among the first to do research on migrants and migration in Sweden. A central character in her account, the Turkish academic and journalist Şahin Alpay, was arrested after the putsch attempt in Turkey last year and remains in prison.

History and anachronism: Kristina Fjelkestam, professor of gender studies and author of the chapter on the 1920s, writes about temporality, chrononormativity and our desire for history. Anachronism, she argues, is necessary in order to estrange ourselves from the past and so to properly engage with it. Hanna Nordenhök, meanwhile, conducts a poetic interview with the German poet Anja Utler (b. 1973); in their exchange, the 1940s emerges as a painful and sometimes violent silence in Utler’s Bavarian childhood. And writing on the 1980s, the poet Jila Mossaed provides a reminder of the limits of historical knowledge: ‘Despite all the figures, the names and the different symbols we have given to time in order to frame it and to tame it, we have failed. Time is perceived differently by different individuals.’

More articles from Ord&Bild in Eurozine; Ord&Bild’s website

Wespennest (Austria) 173 (2017)

‘Cultural heritage is not a value in itself but depends on the heirs deciding whether they want to accept the inheritance, to understand it as a living enrichment, to treat it as a monument with an ethical-didactic function, or to fritter it away, reinterpret it or destroy it.’ With this thought, Wespennest editor Andrea Zederbauer introduces an issue of the Viennese literary magazine on ‘inheriting culture’.

Palmyra: German archaeologist Andreas Schmidt-Colinet worked at Palmyra for thirty years before the civil war in Syria broke out. In an interview (in German here), he criticizes the international reaction to the vandalization of the archeological ruins by ISIS in 2015. Concern about the physical destruction of the site overrode consideration of the meaning of the violence: the denial of the existence around 2000 years ago of a multi-religious, multi-ethnic and multi-lingual society.

The tendency continues in calls for the ruins to be reconstructed, Schmidt-Colinet argues: ‘There is a neo-colonial undertone in this discussion that I don’t like. According to this argument, what is to be reconstructed are the temples uncovered by “our” archaeologists for “our” tourists’. … What needs to be reconstructed in Palmyra first is the modern city, a minimum of infrastructure, homes, a water supply (there has been neither running water nor electricity in Palmyra for two years), a kindergarten, a school, a hospital, a place of worship, a cemetery.’

Also: Ferdinand Schmatz on the Canaletto veduta ‘Vienna, seen from the Belvedere’, regularly cited in justification of Vienna’s status a UNESCO World Heritage site. Schmatz argues for a multivalent view of the city rather than that of mono-perspectival conservationism. And Georg Traska investigates the ‘aesthetic absence of history’ in the Tugendhat Villa in Brno, drawing on contemporary and historical photographs.

Disinformation and democracy: The history of news is the history of the confusion between the real and the fake – with that master of disguise, the devil himself, never far away. Today, too, demonic involvement is readily invoked, perhaps to avoid the awkward question: what is the price of reliable information? Medievalist Valentin Groebner on the problematic concept of post-truth.

More articles from Wespennest in Eurozine; Wespennest’s website

Mittelweg 36 (Germany) 4-5/2017

Mittelweg 36 turns its attention to ‘anti-academicism’. The title of the introduction – ‘Study against the university’ – sums up what anti-academicism is not: anti-intellectualism or hostility towards higher education.

On the contrary, write guest editors Hanna Engelmeier and Philipp Felsch, anti-academicism has been central to the identity of intellectuals since the late-1800s, if not longer. Allegations that universities produce useless knowledge, that they give rise to conformism and mediocrity, or that they are the ideological arm of the state, are as old as universities themselves.

However, the idea that universities prevent knowledge can be highly problematic in ‘post-factual’ times such as ours: ‘The crisis of truth, which we have been discussing ever since the victory march of populist rightwing governments, essentially seems to be a crisis of institutions: a crisis of the universities, the media, the courts and the parties, and a symptom of their damaged or contested legitimacy. The question how far institutions should be seen as being either obstructive of knowledge or conducive to it is therefore of special political importance.’

Politicization: If universities want to survive, writes Eva Geulen, then ‘they must become politically radical, form a broad alliance with other institutions, including the press, meet demands to take a public-political stance, and take to the street: in other words, become thoroughly anti-academic, until what is said and heard is what needs to be said and heard right now.’

Also: Patrick Eiden-Offe on the Young Hegelians whose politicization during the Vormärz was accompanied a growing distance from the universities; and Stefan Höhne on the numerous ‘anti-universities’ founded in western European universities around 1968.

More articles from Mittelweg 36 in Eurozine; Mittelweg‘s website

New Eastern Europe (Poland) 11–12/2017

Central Asia is the focus for the new issue of New Eastern Europe, which asks if the ‘Stans’ represent a ‘forgotten region’.

Filippo Costa Buranelli takes issue with a familiar trope, the ‘Great Game’ characterization of great power rivalry in Central Asia, which he says ‘is still a widely adopted and popular metaphor, rooted in geopolitical thinking and aimed at simplifying the reality’. He identifies a number of assumptions, not least that the five former Soviet republics that form the core of the region are basically alike. But ‘the region is not homogeneous … Central Asian republics have rejected an overly regional agenda … asserting their own individual importance and strength.’

Buranelli concludes that neither the players nor the pieces in the current ‘Great Game’ agree on the rules. The metaphor, ‘rather than faithfully representing, clarifying and resembling the complex regional dynamics of Central Asia, obscures them like the worst of clichés.’

The next Crimea? Naubet Bisenov reports from northern Kazakhstan about fears of a Crimea-style operation by Russia to ‘retake’ a chunk of territory in which ethnic Russians are still a majority. A young ethnic Russian in the Kazakh city of Petropavlovsk tells Bisenov that ‘little green men’ are unlikely to appear there: ‘we have too many police and other security forces in the country. People do not even discuss the situation.’ Nevertheless, the Kazakh authorities seem to be monitoring the situation. Attempts by Bisenov to contact a Russian nationalist group elicit a call from ‘police top brass’. Meanwhile, the government is actively encouraging Kazakh immigration to the region: ‘ethnic Kazakhs [are] becoming increasingly assertive in speaking Kazakh and leading a more traditional way of life’.

Down town: Emil Staulund Larsen and Noah Groves travel to the town of Kupiškis, in north-eastern Lithuania, where ‘something lurks underneath the surface of this quite ordinary city’ – a place dubbed ‘the valley of death’. In 2015, it had the highest suicide rate in Europe: 113.8 per 100,000 people; four times higher than the national rate, and 40 times higher than in Greece (which has the lowest suicide rate in Europe). ‘There was no work’, says the mayor. ‘People had nothing to do and they would drink too much alcohol.’ The locals have come up with ‘the Kupiškis Algorithm’ to deal with helplessness, and are challenging acceptance of suicide, which is unusually high in Lithuania.

More articles from New Eastern Europe in Eurozine; New Eastern Europe’s website

Esprit (France) 11/2017

In Esprit, the editors investigate the myriad instabilities that currently plague our conception of democracy. In Spain, constitutionalism has been reduced to a ‘simulacrum’, with the violent enforcement of the rule of law recalling ‘the dark days of Francoism’. Outside Europe, China ushers in the nineteenth congress of the communist party, while Russia promises security and progress in the name of an obscure variety of liberty.

Macron and the suburbs: Tucked between all this is the attempt by the ‘suburban French’ to reinvent themselves politically. Erwan Ruty describes a new French president who advises citizens that, despite ‘uberization’, work is still a noble pursuit. Macronism, writes Ruty, speaks to a new spirit of meritocracy in the suburbs, summed up by rapper Nikkfurie in the line: ‘The proletariat are the bourgeois in the waiting room’. The young minorities in these communities have no problem marching for both the Right and the Left. Herein lies the advantage of En Marche!, a political party without any institutional roots.

The just institution: Despite the appeal of the non-institutional, a dossier on philosopher Paul Ricoeur appeals to the capacity of just institutions to ‘make our lives better’. As the world becomes more complex and individualized, writes Jean-Louis Schlegel, institutions prevent the total decay of a ‘good life with and for others’. Universalism, Schlegel argues, is unable to respond to the questions of inclusion and identity raised by Macron. As Ricoeur points out, an institution is just insofar as it strives to bring about equality.

More articles from Esprit in Eurozine; Esprit‘s website

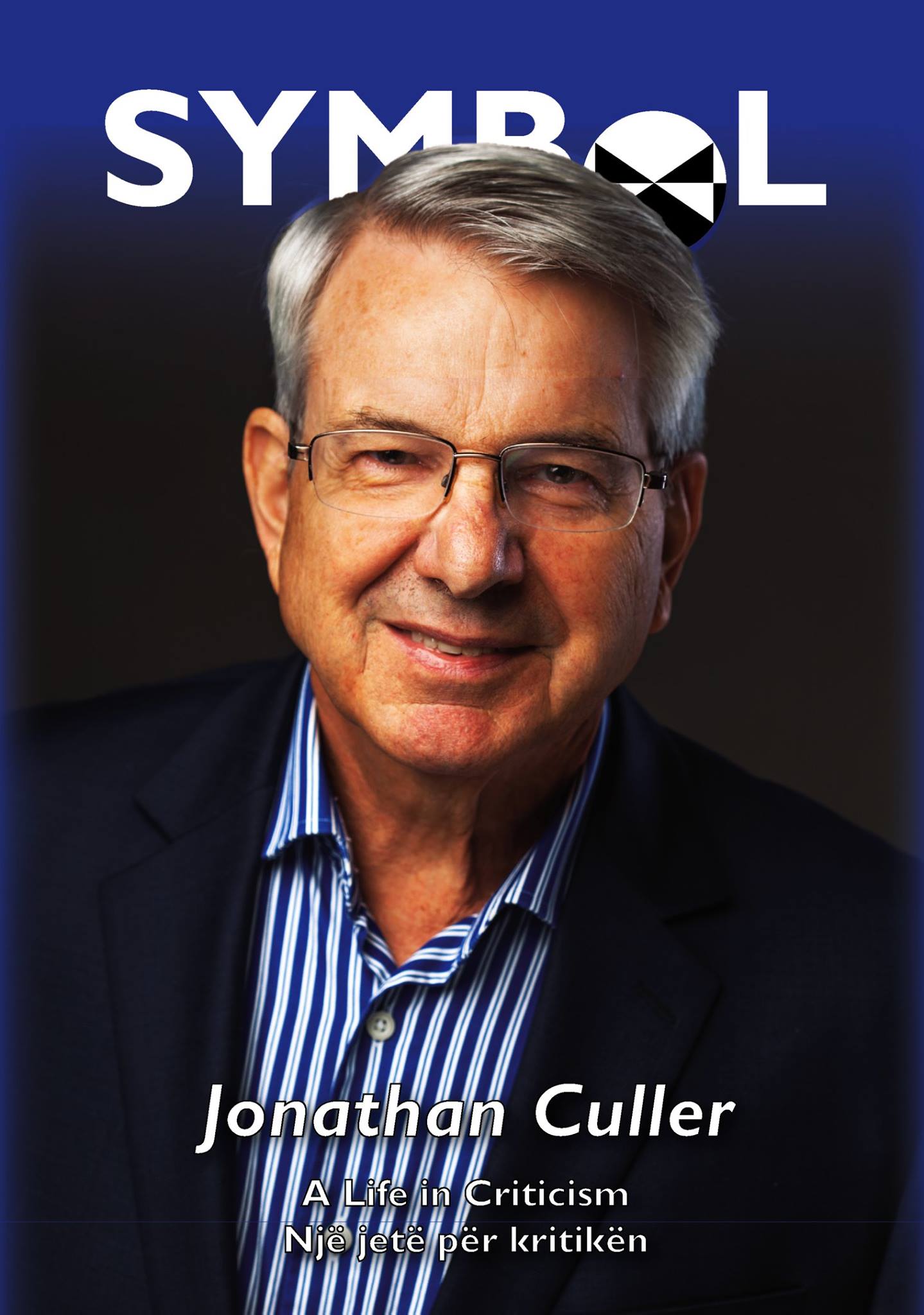

Symbol (Kosovo) 11 (2017)

In Symbol, Ag Apolloni interviews Jonathan Culler, the US literary scholar who did much to introduce ‘French Theory’ to Anglo-Saxon academia. As Culler recalls, it was an uphill struggle. As a young researcher at Oxford in the late 1960s, ‘there was really no one else … interested or knowledgeable about structuralism. Feeling that I knew about these things more than anyone in Oxford … doubtless helped me adopt an authoritative tone’. It was only in 1977 that he became a professor of English and comparative literature at Cornell, by which time structuralism and post-structuralism were on their way to becoming de rigueur.

Asked about the concept of literary interpretation, Culler makes an interesting observation: ‘Criticism is usually evaluative, or focused on the nature of literature in general and its cultural significance. And in studying literature prior to the twentieth century, students did many things other than interpret works: they translated them, they imitated them, they described their formal and rhetorical structures and components. I think that interpretation should be seen as one way of encountering literature among others.’

Disinformation and democracy: In Kosovo, fake news thrives amidst political corruption, a weak cultural sector and the absence of regulatory bodies. Without a normalization of the political, institutional and social situation, a responsible media can never exist in the recently independent Balkan state, writes Orjela Stafasani. Also: a translation Marci Shore’s intellectual history of concepts of truth, East and West.

Literary history: Robert Wilton on Albanian writer and social democrat Musine Kokalari (1917–1983). Persecuted under communism, Kokalari’s legacy continues to be stifled, reflecting a deeper discomfort about the realities of the past. And Primo Shllaku on Albanian poet Frederik Rreshpja (1940–2006). Rreshpja’s eccentric personality is mythologized at the expense of critical receptions of his innovative poetry.

More articles from Symbol in Eurozine; Symbol’s website

The Eurozine Review presents a selection of the latest issues of Eurozine partner journals, summarizing their contents in English as a way of encouraging cultural and political dialogue between national public spheres in Europe.

Published 10 November 2017

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.