After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Clifford Geertz predicted that the world would be characterized by ‘deep diversity’, ‘a sense of dispersion, of particularity, of complexity and of uncenteredness’ rather than unified world order, as stipulated by the then consensus.

In an age of identity politics and culture wars, Geertz’s insights sound even more powerful today than they did at the time. According to the American anthropologist, our task is ‘to penetrate the dazzle of the new heterogeneity’ and analyse the paradox that confronts us: the world is both more global and more divided than ever in human history. The sense that we find ourselves in ‘a scramble of differences in a field of connection’ is even more immediate, as is the realization that there is a multiplicity of alternative, sometimes conflicting and clashing, visions of the good.

This focal point, inspired by a lecture that Geertz delivered in 1995 at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, summarized in the institute’s magazine, will engage with these issues. It follows the launch of a research programme of the same name at the institute in January 2023, coordinated by Clemena Antonova.

The collection of essays is an extension of earlier focal points ‘Eurasia in Global Dialogue’ (2018-2023, led by Clemena Antonova) and ‘Russia in Global Dialogue’ (2012-2018, led by Tatiana Zhurzhenko). Further texts have been contributed by journals in the Eurozine network.

In collaboration with

Unlike their nineteenth-century precursors, anti-European intellectuals in Russia today are neither engaged in dialogue with the West, nor do they realize that their ideas about European decline are themselves derivative.

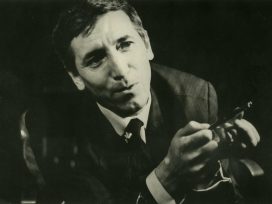

From being the literary darling of Bulgaria’s communist regime, Georgi Markov became its most vociferous critic. Yet his memory, in so far it exists at all, has been reduced to his spectacular assassination in London. On Markov’s work and the lives of the man behind it.

Human, all-too human

Anastasia Filippovna’s ‘Portrait of Christ’

If Jesus is portrayed as fully human, can his divinity be rescued from the manifestation of what is visibly ‘all-too-human’? Christ’s depiction in Dostoevsky’s novel ‘The Idiot’ creates layered religious, historiographical and artistic readings.

For three decades, Memorial has delivered the facts that have enabled Russians to seek the truth about the Soviet past. Without its research, international accounts of the GULAG would also have been impossible. The attempt to close the NGO is the latest move in the Putin regime’s attempt to monopolize history.

Italy’s enthusiasm for Chinese investment has recently cooled, as transatlanticism, security risks and domestic resentment become decisive factors. The Italian change of heart is shared by the EU, which is finally developing a coordinated and values-based response to Chinese economic activity in the bloc.

The story of the Sputnik V vaccine

Vaccine nationalism and Cold War tropes abound

Russia’s COVID-19 vaccine could be one of the most effective jabs available. Yet, its media coverage in the West has revived Cold War stereotypes. Vladimir Putin has also triggered suspicions. Nevertheless, the medical legacy from the Soviet era has prepared researchers precisely for such emergencies.

Russia and Turkey have moved from confrontation to cooperation. But their shared interests have had deleterious consequences for the Kurds in Syria and Crimean Tatars in Ukraine. Tensions continue in Nagorno-Karabakh and Libya. And their support for right-wing authoritarianism in the Western Balkans is undermining liberal democratic values.

Icons and the avant-garde

The Costakis collection

In an era when the sole approved artistic doctrine in the USSR was Socialist Realism, the Moscow collector George Costakis built up a unique body of Russian avant-garde art, alongside numerous early Russian icons, revealing deep-rooted links between the two genres.

The description of Russia’s anti-Putin protests of 2011–12 as ‘middle class’ was only partially accurate and used to discredit them. The middle class label applies even less to the Belarusian protests of 2020, whose core message is that dignity and respect are not reserved for a privileged minority.

Despite the ceasefire, Nagorny Karabakh’s status remains unclear. Any lasting solution must deal with the anxieties of precarious nations and unachieved statehood. On the historical roots of the long-standing conflict and the legal ambiguities of a war in contested territory.

Sparked by raids on the offices of the Bulgarian president Rumen Radev in July, after mounting dissatisfaction with the Borisov government, the ongoing protests in the country express broad resentment towards a powerful clique whose corrupt methods hark back to the criminal 1990s.

Exile, dignity and love

An Istanbul story

Russian refugees influenced Istanbul’s cultural life from the 1920s despite the Turkification policies of the new republic. The Sevastopol-born sculptor Iraida Barry’s life in exile and love for the city is a piece of this history. However, admiring the Russian diaspora shouldn’t have meant demeaning others – as ended up happening in US press. Ayşe Kadıoğlu revisits a life exiled to Istanbul, while longing for the heartbeat city herself.

The conversion of the Hagia Sophia was intended as a demonstration of strength to Erdoğan’s conservative Muslim constituency and the wider Islamic world. But calculations of political advantage have also caused the weak response of the West. World cultural heritage has been dealt a huge blow, writes a leading Russian Byzantinist.

Russia’s popular vote approving the ‘zeroing’ of Putin’s terms has been hailed by the regime as a triumphant demonstration of trust. Putin’s uncontested status as supreme authority has indeed been reinforced. But will the legitimacy bought by the vote be enough to stem growing uncertainty among elites and declining support among urban constituencies?

Vladimir Putin’s anger and jealousy has taken down many proactive leaders throughout Russia – and left the country vulnerable to crisis. The oil price war against Saudi Arabia backfired, and a recession was already in motion when coronavirus hit the country.