86 articles

In November 2018, a group of French writers published a manifesto in Le Monde demanding that the novel be ‘not just a commodity, nor even a means-to-make-people-read, but a burning and necessary affair: a contemporary art’. Our ‘monstrous times’, they claimed, ‘require monstrous fiction, deformed novels, which border on catastrophe, risk poetry and do not shy from the new and the unspeakable’.

If literature is a way to raise questions about the human condition, then in the current global context – war, mass migration and the ‘crisis of multiculturalism’, political Islam, populism and a denunciatory political culture, not to mention climate crisis and the debacle of neoliberal economics – it would seem to have its plate full.

Much of the writing arriving on the scene today noticeably lacks the post-modernist suspicion towards reducing literature to ‘authorial intention’, a ‘message’, or a ‘theme’. Does this mean we are seeing a new littérature engagée? Or are our times so tumultuous that they demand a tumultuous literature?

In her book, The Balkans: From Geography to Phantasy (2013), the Croatian essayist Katarina Luketić warns that ‘every trauma is a spring, the more you repress it the stronger it comes back, each repression makes it more present, even though invisible, everything that gets thrown out through the window comes back through the door.’

Over the last decade, we have often seen that the literary works which have been most discussed – which have become emblematic for a pressing problem – were not necessarily written with a progressive purpose. Often, they are agnostic, sceptical or cynical to the point of being seen as reactionary (the prime example is Michel Houellebecq, one of the few such authors to be received across Europe). Other writers and critics clearly endorse the idea of the existence of a ‘corridor of opinion’ – an åsiktskorridor in Swedish or a Gesinnungskorridor in German – where lines defining acceptable public speech are constantly drawn.

The explosiveness with which the decades-old controversy around Peter Handke resurfaced at the end of 2019 illustrated one thing very clearly: that a writer who even twenty years ago would have been viewed as ‘uncomfortable’, and for that reason worth reading, is today – in the age of the social media ‘shit storm’ – exposed to a rapid process of discrediting. Whether or not one considers Handke to have legitimated genocide or to be a torchbearer of poetic autonomy, the controversy said as much about how literature is talked about today as what it talks about.

Against the backdrop of the rise of the right, literary debate seems to be seeking consensus and a shared set of values. Others argue – citing political correctness or bourgeois hypocrisy – that the task of art and literature is precisely to voice what would otherwise be seen as unacceptable. Conversely, what was once subcultural playfulness or post-modernist experiment is gaining political momentum through internet-based rightwing movements. How to respond to claims of censorship, on the one hand, and the anti-liberal co-opting of emancipatory literary practices on the other?

According to Pascale Casanova, a ‘literary world’ or universe exists relatively independent of the everyday world and its political divisions, ‘whose boundaries and operational laws cannot be reduced to those of ordinary political space’. The literary greats, she argues, ‘have managed, by gradually detaching themselves from historical and literary forces, to invent their literary freedom, which is to say the conditions of the autonomy of their work.’ (The World Republic of Letters, 2007.)

Has literature become hostage to politics and ideology? Must it choose between artistic freedom and political engagement? If so, which side should it take? Are there writers today who whisper into the ears of populists or help them win support? What is the line between propaganda and literature? Is artistic autonomy possible at the current moment? Is the writer’s responsibility to art greater than her responsibility to her community? How does a writer navigate through these minefields?

The focal point ‘Consensus and controversy’ collects articles commissioned exclusively for Eurozine alongside contributions from Eurozine partners. It reflects the concern with literary subjects shared by the great majority of journals in the Eurozine network. The series is ongoing and will expand over the course of 2020 and beyond. We hope you find it thought-provoking!

Miljenka Buljević (Booksa, Croatia)

Audun Lindholm (Vagant, Norway)

Simon Garnett (Eurozine)

For the novelist Nirmal Verma (1929–2005), Prague was the gateway to a European sensibility that bypassed the English language. Even after his ‘homecoming’ in the 1970s and growing interest in Indian identity, European culture and literature remained central to Verma’s work.

‘My pain is deciphered and therefore human. She, on the other hand is a muted creature; easier to misinterpret and, finally, dehumanize.’ Ece Temelkuran describes her deep unease at being referred to as an ‘exile’ and how, despite that public role, she shares a fundamental experience with the unnamed refugee.

In a politicized age, literary debate seems to be seeking consensus. But many still argue that the task of writers is to voice what would otherwise be seen as unacceptable. Today, the question is as much about how literature is talked about as what it talks about.

Danilo Kiš famously observed that the western bracketing of Balkan literature as narrowly ‘political’ rested on a set of mutually reinforcing stereotypes. Today, following Kiš, Balkan novelists are challenging received wisdom and integrating the political and the poetic in surprising new ways, writes Katarina Luketić.

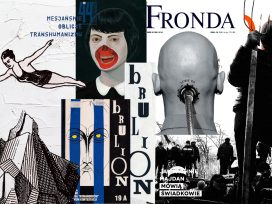

Rightwing literature reappeared in Poland after 1989, having been absent from cultural life during communism. Since 2010, political polarization has caused its significance and visibility to increase. But what defines rightwing literature in Poland? A typology of its motifs and genres, from anti-communism to anti-modernism, historical revisionism to sci-fi.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline based a literary reputation on transgression. He was a prototypical troll, contemptuous of the truth, indefatigable in saying the unsayable, and couching his hatred in irony. And like trolls, he poses a dilemma: engage or ignore?

Boris Vezjak looks into Peter Handke’s controversial Nobel Prize using the analogy of a pizza: whether one should only care if it tastes good and not about the morals of the chef. Isolationists only refer to tastiness, while holists’ criticisms don’t necessarily invalidate the award.

Like a prophet, Mahmoud Darwish is positioned between the tragic past of the Palestinian nakba, the present of occupation and exile, and hopes for a liberated future. Zeina G. Halabi places him in the context of the Arab enlightenment and the post-Arab Spring world to offer Palestinian liberation as a way of redeeming all humanity.

After moving from Johannesburg (Jo’burg) to Gothenburg (Go’burg), filmmaker Jyoti Mistry struck up a friendship with someone who went the other way: Katarina Hedrén, who was adopted by a white Swedish family, and moved to South Africa as an adult. This deeply personal take on race shows how ‘colour-blindness’ denies that racial prejudice exists but robs people of colour of words to talk about the discrimination they face.

In a politicized age, the scepticism and elegance that have traditionally characterized the art of the essay can seem extravagant. In the US in particular, there have been calls for essayists to trim their sails and position themselves explicitly. Does the new mood of engagement mean that the essay’s habitual rejection of dogmatism is passé?

How can a writer possibly contribute to averting catastrophic climate change? By putting literature into an ‘ecological template’, writes the Icelandic poet and novelist Sjón. Together, writers are responsible for the ecosystem of literature as a whole.

‘The novel enjoys a freedom that no other literary genre enjoys. This is a privilege, and perhaps also a guarantee of its sustainability, on condition that we know how to make the most of that freedom.’ The novelist Javier Cercas talks history and fiction, and his influences in the Spanish language tradition.