86 articles

“The eastern European ’68ers formed the backbone of the democratic opposition and dissidents, whereas we, the somewhat older ’56ers, only joined in with certain reservations, because we had a closer acquaintance with defeat.” The Hungarian writer György Konrád takes an ironic look at the ’68ers from the perspective of a participant in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

Vierzig Jahre nach Beginn der Frauenbewegung in Deutschland hat sich die Situation der Frauen geändert. Trotzdem sieht sie sich immer noch ähnlichen Problemen gegenüber wie schon ihre Mutter. Mittels eines Vergleichs stellt Stefanie Ehmsen die Schwächen und Stärken der deutschen und US-amerikanischen Frauenbewegung heraus.

As the fortieth anniversary of 1968 draws to a close, the focus of interest shifts to next year’s anniversaries commemorating twenty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. On 30 May, a debate was held at the Academy of Arts in Berlin entitled “Crossing 68/89”. The participants, leading protagonists of 1968 and 1989 in eastern and western Europe, were asked to discuss the Prague Spring and the student protest movement in the West in a European perspective – with particular reference to the cataclysmic year of 1989. First published in German in Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, Eurozine translates the debate into English.

Aleksander Daniel locates the birth of the dissident movement in an appeal broadcasted by western radio on 11 January 1968, protesting against the trial of Aleksandr Ginzburg and three other system-critical writers. “This represented a strike against one of the standard elements of Soviet psychology, one which had been cultivated over many decades: the concept of ‘hostile encirclement’, the complex of the ‘besieged fortress’. To appeal to world public opinion, to the ‘enemies’ – i.e. airing dirty laundry in public – was equivalent to treason, to betrayal of the homeland.”

The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 caused the Soviet empire to lose its internal logic even for the communist faithful, writes Samuel Abrahám, who bore witness to the events. Yet today, the naivety of the reform communists of the 1960s serves as a pretext for the cynical dismissal of any vision of a better political system.

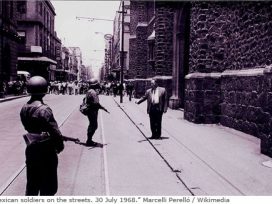

Sports journalist Brian Glanville was sent to Mexico City in 1968 to cover the Olympics but instead found himself reporting on the anti-government demonstrations at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas. Despite the ensuing massacre, he recalls, indifference reigned at the Olympic Village.

To Polish ears, the language of the Western revolutionaries of ’68 “carried the burden of oppression”, recalls Aleksander Smolar. Western ’68ers were often hostile to supporters of the Warsaw March revolt and indifferent towards the subsequent “anti-Zionist” purges. Yet the events were disastrous for Polish Jews at the time and are still relevant forty years later, writes Aleksander Smolar.

Mykola Riabchuk recalls how the politics of the Prague Spring filtered through to the Ukraine until the crackdown on ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism’ in 1972-73; and how, during perestroika, the roles were reversed and he was able to bring banned literature to friends in Czechoslovakia.

In an interview conducted a year before his premature death, Rudi Dutschke explained to Jacques Rupnik the reasons for the German Left’s failure to understand what was at stake in Czechoslovakia in 1968. “In retrospect, the great event of ’68 in Europe was not Paris, but Prague. But we were unable to see this at the time.”

Parallels between May ’68 and the Prague Spring are largely the result of the simultaneity of the events; in important respects, the political goals of the two movements were antithetical. Nevertheless, central European dissent had a significant impact on the French anti-totalitarian Left after 1968, argues Jacques Rupnik.

The failure of the German extra-parliamentary opposition to reflect upon its gradual slide towards violence led to the leftwing terrorism of the 1970s, writes Christian Semler. It was only with the ecological movement that pacifism came back onto the agenda. For the Left today, the question of the state monopoly on the use of force remains as central as ever.

Despite the tendency of decennial commemorations to cement the “official version” of May ’68, important questions remain unanswered. What exactly was the role of the police in the escalation of the violence (including the much overlooked fatalities in June)? Why did the Renault factory workers reject the concessions obtained in the Grenelle agreements? And was de Gaulle on the point of stepping down when he went to Baden-Baden? Chris Reynolds points out some blind spots in the increasingly stereotyped interpretation of the events in France forty years ago.

Large-scale social movements often behave provocatively but with the aim to make more space for democracy. The latest of these is the global justice movement born in Seattle in 1999. Magnus Wennerhag’s new book is the first major Swedish study on the impact of this movement. In the extract Arena publishes here, he shows how it differs from the movements of 1968, being more political and more directed towards international institutions and globalized democracy.