‘If I take a book and never return it, in other words, steal it, what should I do according to the rules?’ Such questions have been addressed more and more frequently to librarian Natalia from a small town in the Moscow region. In her opinion, this is how readers try to save certain books or add them to their personal libraries while they still have the chance. ‘People ask us, “have you written off anything yet? Write it off into our caring hands,”’ Natalia says.

According to her, some libraries have already started getting rid of books by so-called ‘foreign agents’, even though there are no such legal requirements. Works by Dmitry Glukhovsky, Mikhail Zygar, Dmitry Bykov and other authors are included in the ministry of justice’s registry and tossed out, along with other worn-out books, for recycling. As Natalia put it, libraries ‘fell before the first shots were fired’.

She has heard from colleagues that they have already received an official letter recommending the removal of ‘foreign agent books’ from reading rooms ‘not to irritate the public’. A list was attached to the letter, but she has not seen it herself. ‘We haven’t reached Fahrenheit 451 yet, so the books aren’t being burned; they’re just written off and sent for recycling. Vigilant citizens would walk around and say, “they’ve removed Akunin, good job,”’ Natalia adds, referring to those readers who do not want to ‘save’ the literature.

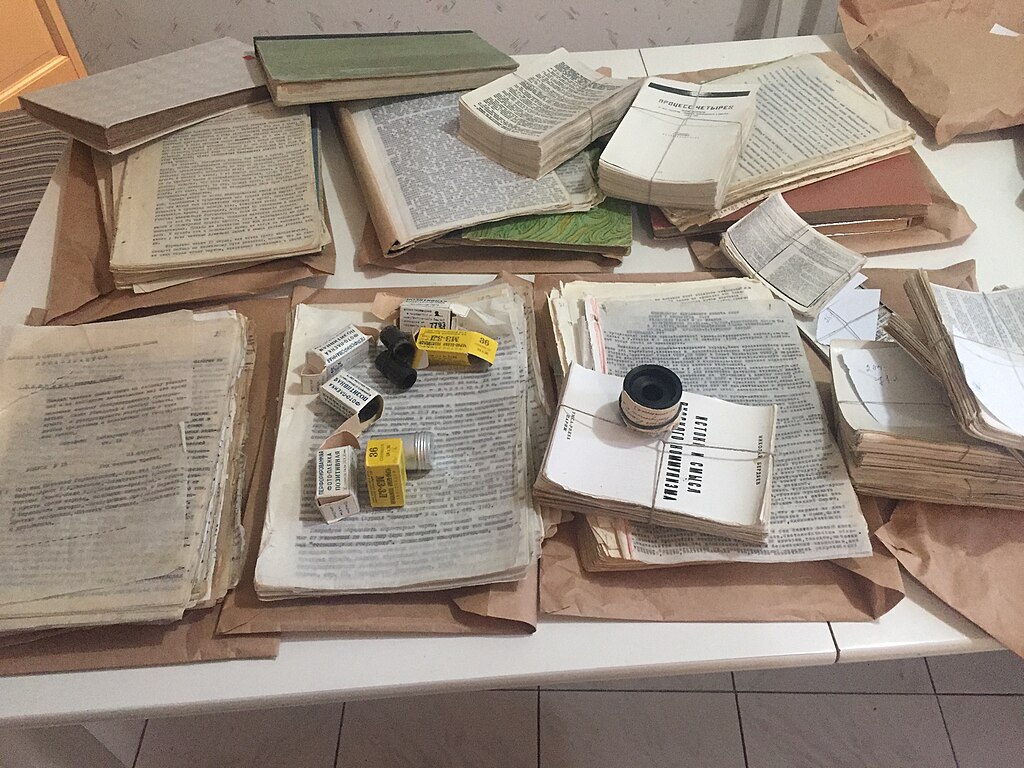

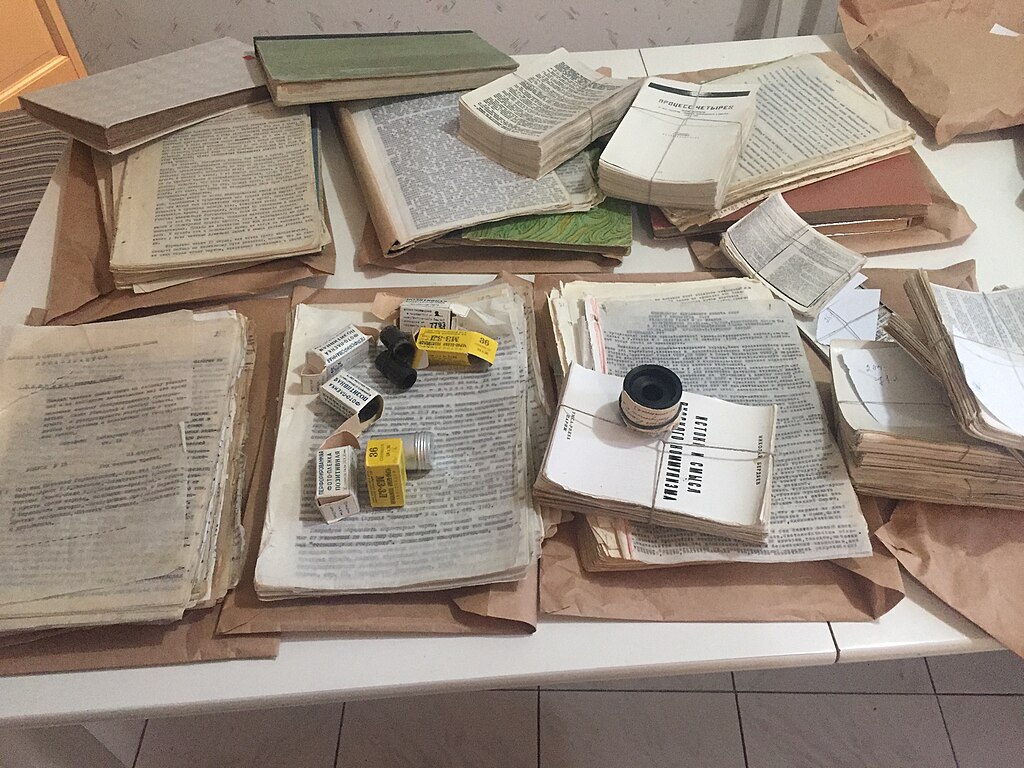

Russian samizdat and photo negatives of unofficial literature in the USSR. Image by Nkrita, via Wikimedia commons.

Increased control

At the library where Natalia works, books by foreign agents have not yet been sent for recycling, but they have been hidden in a closed collection. At first the librarian printed labels about supposed foreign agents that read ‘This material was created by…’, but her colleagues dissuaded her from marking the books in that way, saying it ‘dishonours the honest name of librarians’. For now, they have decided to just stick on an 18+ age restriction label, as required by law.

Natalia mentioned that sometimes books by foreign agents returned by readers are mistakenly placed in the reading room. However, books that contain descriptions of LGBTQIA+ content require closer monitoring. For example, the 18+ book A Summer in the Red Scarf (Лето в пионерском галстуке) by Elena Malisova and Katerina Silvanova (both recognized as foreign agents), despite being in high demand among readers, is more likely to be tossed away than to be hidden in the collection. Since the book allegedly promotes LGBTQIA+ themes (the LGBTQIA+ movement is recognized as an extremist organization in Russia), Natalia said that if this book is accidentally found on the shelves, library staff could be held accountable for promoting ‘gay propaganda’. However, there is currently no liability for displaying books by authors labelled as ‘foreign agents’.

Recently, Natalia’s library was renovated and now more young people come there to work and visit exhibits. People also seem to have a renewed interest in books. Natalia believes that reading has become a new luxury and mentioned that the trend for books was even described in Vogue magazine. She explains the increased control over libraries: ‘In my opinion, our authorities are trying to take control of everything vibrant and positive that unexpectedly emerges in our country. Naturally, both the authorities and concerned citizens have now started paying closer attention to libraries as well.’

At a university library in the Northwestern Federal District, they have already heard about the pending law. While library management has not given clear instructions on what to do with books by foreign agents, the staff are keeping an eye on the justice ministry’s list themselves. According to the librarians, they regularly monitor the ministry’s website and check their electronic catalogue to see if they have any new books by foreign agents so they can mark them accordingly. They report this to their superiors every month and warn colleagues about which books should be removed from open access. However, some librarians are in no rush to take such initiative.

‘I told the subscription desk worker that we need to remove Igor Lipsits’s economics textbook. But my colleague replied that she would only deal with those editions once she had an official document on her desk,’ says Ksenia, a library employee. Igor Lipsits

is a Russian economist and a former professor. He created Russia’s first complete series of economics textbooks for the seventh through to the eleventh grade. In March 2024, the justice ministry recognized Lipsits as a foreign agent.

If a reader wants to borrow a foreign agent’s book to take home, the book will be provided from the closed collection with a warning about the author’s status (provided the reader is over 18). ‘In the closed collections, we added bookmarks with an 18+ label and a note that the author is included in the [foreign agent] registry. But this labelling is done more for us, than for the readers. We cannot put official markings on the books because there’s no such directive,’ Ksenia explains.

According to Ksenia, in the municipal libraries in the Northwestern Federal District, some libraries have already begun marking books on their own initiative. At the library where Ksenia works, there are over a hundred books by authors labelled as foreign agents. The most frequent are works are by Boris Akunin, Lyudmila Ulitskaya and Dmitry Bykov. These books were always popular, but recently, Ksenia feels that they have been requested even more frequently. ‘Perhaps people are afraid they won’t be able to read them later,’ she suggests.

‘Some people, though, may refuse to read them out of principle, because the author is a foreign agent. That’s a personal choice. The main thing, of course, is not to go overboard with all these laws. Many books were written long before any of these events [and restrictive laws], and it’s unlikely that the author included anything illegal in them,’ the librarian reflects.

In the literary world, people still laugh off the foreign agent label while they can. ‘I’ve read foreign agent books myself, of course. I managed to read many of them before the authors received that status. Honestly, I think the foreign agent law is very foolish. People joke that being labelled a foreign agent is the best recommendation. And that’s partly true. I was at a book festival in July, I picked up a book by Irina Arkhpova, and when I went to another stand, the saleswoman saw the book and immediately suggested, “We have books by potential foreign agents here, want me to show you?”’ Ksenia smiles.

However, regarding works by authors included on official lists of terrorists and extremists, some Russians have already developed a sense of self-censorship. ‘Not a single reader has asked for books by authors listed as extremists, even though those books used to circulate regularly,’ the librarian recalls.

Russian law prohibits the distribution of extremist materials, as well as their production and storage for the purpose of dissemination. While the situation with extremist literature is relatively clear it is still unclear how the new law will legally restrict access to books by foreign agents (and include those who may not only be authors but also editors, publishers, illustrators, or even just contributors to a preface). The Russian Library Association’s statement says that libraries, in their work, are also guided by the constitution which guarantees citizens the right to freely access information.

Libraries are hiding

Recently, at Russian national library conferences, special sections were held where staff discussed the issue of foreign agent books. For example, at the Corporate Library Systems: Technology and Innovation Conference in June 2024, an entire roundtable was dedicated to this issue. This was titled ‘Foreign agents, inventory, or inspection: questions that need solutions’. However, the participants of the discussion in St Petersburg perhaps did not leave with a clear understanding of how the proposed legal amendments can be applied in practice. One of the presenters – Tatiana Petrusenko, an executive secretary of the section on library collections – noted that of all the laws restricting access to information, the law on foreign agents is ‘the least justified and least adapted to library activities’. She mentioned that prosecutors in Russia are already inspecting libraries, apparently to check compliance with norms that have not yet been enacted.

‘Inspections are currently underway in Russian libraries [in Yaroslavl, Vladimir, Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and other cities]. Prosecutors or their assistants are visiting libraries with those lists,’ says Petrusenko. She adds that it’s a ‘list of authors who have been labelled as foreign agents and thus they [prosecutors] are looking for them in libraries’.

A list of 38 foreign agents can be found in open access on library websites. Library staff compiled the list themselves, relying on data from the ministry of justice. Some institutions, such as the Moscow Regional Universal Library, even publish something along the lines of ‘guidelines’ for handling books by foreign agents. For example, they advise colleagues to go to court if ‘a librarian or library visitor suspects that a work by an author recognized as a foreign agent contains signs of extremist literature’.

When libraries seek clarification from authorities, they are often ignored. ‘When we hold our library events, we often invite representatives from the ministry of justice or the prosecutor’s office, but they never come because they avoid giving any recommendations, especially on such a tricky and unclear issue like foreign agents,’ Petrusenko complains.

We have been through this before

Lilia lives in the same town near Moscow as Natalia but works in a different library. She admits to having a negative opinion about some foreign agent authors but condemns book censorship in general: ‘We’ve already been through this. We “burned” [Lev] Gumilev, [Boris] Pasternak, and [Joseph] Brodsky. So there’s no need to do that again. The content of these books is worthy. Yes, some people behave badly, but how are the books at fault?’ the librarian reflects.

She gave examples of two writers: ‘Take Boris Akunin, for example. His works are excellent, light reading. Want to relax? Unwind your mind? Good, quality reading. For those who enjoy historical detective stories, he’s your guy. I recommended him to everyone. Take Lyudmila Ulitskaya. Yes, she’s saying nonsense now, but her texts are brilliant, her language, her style. Try finding another author who writes like that.’

In recent years, the work of librarians has changed significantly. According to Lilia, they now have to do everything: manage social media, know how to take a photo and organize events. The one hour that used to be allotted to librarians for familiarizing themselves with new books, so they could later give recommendations to readers, has been cancelled. The library where Lilia works has undergone renovations, with new ceilings, floors, windows and blinds. However, there was not enough funding to renovate the walls or furniture and the renovation itself dragged on for five years. The library is transitioning to digital operations: all books are being entered into an electronic database and obtaining a library card must now be done through the government services platform Gosuslugi (a unified portal of state and municipal services).

‘The state needs to know everything – what you eat, where you go. And, of course, the state is interested in your spiritual life and what you’re up to,’ Lilia remarks with sad irony. She opposes the digitalization because she believes books are ‘too personal’ and the right to read in a library ‘should be unconditional’ not only for those who have registered through Gosuslugi. However, she never brought it up to her management.

‘The way it is now: if you don’t like it, then look for a job somewhere else. No one is worried about attrition anymore. Either you adapt somehow, fit into this system, try to align it with your values while having minimal losses for your colleagues and readers, or you don’t work here,’ Lilia says.

In a small library in the Tver region, not many people visit, but there are regular readers. They are mostly retirees and students. The first group often inquire about romance novels and detective stories, while the second are interested in classics and scientific literature. Oksana has been working there as a librarian for three years. According to her, the job is hard and the pay is low (the vacancy for a second librarian has long remained unfilled), but Oksana enjoys the work and loves interacting with people. Once a year, she and her colleagues conduct an inventory check and remove ‘morally outdated’ and worn-out books. Some of these are placed on a table for ‘book-crossing’, but most are collected by a truck and taken for recycling. The books by foreign agents have been moved to a storage area for now.

Authors are not the only ones who suffer

Olga works in one of the libraries in a city with a population of over a million. Due to an internal directive, they have already disposed of books by foreign agents. Just in case, they have even closed the book-crossing area: what if someone brings in a ‘prohibited’ book and the librarians do not notice in time?

‘We were sent a list of books that needed to be removed, and we catalogued these books as defective. What happened to them afterward? They were taken away. Most likely, they were sent for recycling. However, some staff take them home, and sometimes readers steal books by foreign agents. They borrow them on their cards and then never return them. In exchange, they buy other books or reimburse the cost in cash,’ Olga explains.

An employee from one of the libraries in the Vologda region shared that she also took home several books by foreign agents to preserve them, as she fears they might someday be confiscated. Library management tries to play it safe; they are not willing to take risks for the sake of books. According to Olga, librarians find it very difficult to decide on the disposal of works by foreign agents. She sees the reason for this hidden conflict in the fact that libraries are managed by staff managers rather than librarians.

‘For the manager, the main goal is to avoid problems and remain in their position, while the value of books is relative to them,’ Olga gestures helplessly. According to her, books by foreign agents have also been removed from children’s libraries, including the book I am a Snake by Andrei Makarevich.

‘Authors are not the only ones who suffer, but also the illustrators and the entire team that would work on the book. It is especially sad for collections that include one of the foreign agent authors. We are forced to remove them as well. “Adequate librarians” do understand that this is a major problem. There are no official orders or regulations, and the value that the library holds is being destroyed by the library itself,’ Olga admits with sadness.

The names of the protagonists have been changed to protect their identity.

This text first appeared in the Russian independent media publication Novaya Vkladka and was written by journalists Miron Samkov, Svetlana Sinitsa, Natalia Baranova and Violetta Grishkovaya. It was first published in English in New Eastern Europe’s issue on navigating uncertainty to help disseminate information and stories about Russia since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.