The face of ‘post-truth’ politics: Observations from the trenches

‘Post-truth’ is a concept that has been much discussed in recent years. But what is it like to experience its effects for real? Mykola Balaban, a history student and soldier, describes how it feels to be attacked with ‘non-existent’ rockets, and how one can come to doubt even one’s own empirical experiences.

The ground was so hard that, even using pickaxes, we could only deepen the trench by 50 centimetres by the time dusk fell. My first day on the front line finished with the preparation of a shelter, and an alarming night began with me leaning against the shallow wall of my trench and trying to accustom myself to the cannonade rumbling around me…

When we read the world news and try to figure out what is going on in far-away countries of which we know nothing, we start to use language and categories appropriate to our own context. Thus, when we want to understand what’s happening in Donbas, we need a definition of events that relies on multiple questions that historians share with other truth-seekers, especially journalists: What? When? Where? Why? How?

In the case of the conflict in Ukraine, one must pick a definition of what is going on from lots of different options. It’s a difficult exercise, demanding a certain amount of discipline, taking into consideration the verity of definitions offered by Ukrainian and international legal actors, plus official statements, media reports and comments by various stakeholders. Take just a few examples of the stock-phrases used to refer to the conflict: ‘Ukrainian Crisis’, ‘Russian war on Ukraine’, ‘separatist uprising’, ‘terrorist war against Ukraine’, ‘Ukrainian civil war’.

Full-scale war in Donbas began on 12 April 2014, when government buildings in the city of Sloviansk in Donetsk Oblast were seized by a well-equipped armed detachment led by a Russian soldier, Igor Girkin operating under the nom de guerre Strelkov, or ‘Sharpshooter’.

Strelkov cut a picturesque figure: tall and lean, with a neat moustache. It was as if Captain Talberg, from Bulgakov’s novel White Guard, had been brought to life – an exemplary White officer, embodying the aesthetic of Tsarist Russia, but a century after the Bolshevik revolution:

… на фигуре Сергея Ивановича ничего не отразилось. Пояс широк и тверд. Оба значка — академии и университета — белыми головками сияют ровно. Поджарая фигура поворачивается под черными часами, как автомат.1

… nothing showed on Talberg’s face. Broad, tightly-buckled belt; his two white graduation badges – the university and military academy – shining bravely on his tunic. Beneath the black clock on the wall his sunburned face turned from side to side like an automaton.2

His devilish appeal attracted patriotically minded young Russians who grew up on the historical novels of Alexei Tolstoy, Valentin Pikul and Boris Akunin. It required an intense intellectual effort to break through this romantic appearance and recognise that behind it lay an FSB agent specializing in secret operations and separatist movements, with experience in Transnistria (1992), Bosnia-Herzegovina (1993), Chechnya and Dagestan (1998 – 2005), and the annexation of Crimea.

In that spring of 2014 I was away from Ukraine, at the Yad Vashem archive in Israel, studying archival materials for my PhD dissertation on violence in Lviv during the first two weeks of the German-Soviet War.

My weekday schedule in Jerusalem consisted of three parts: from the morning until the afternoon I worked with documents; this was followed by a short walk to my accommodation in the north-west part of Jerusalem and two hours of surfing the web for every scrap of news concerning the situation unfolding in Ukraine. At approximately 7pm, I would take an eight-kilometre jog around Mount Herzl, meeting the sunset and listening to the audiobook of Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Jerusalem: The Biography.

Despite my desire to return to Ukraine, I tried to discipline myself, continuing my research in every possible way. At the time, I was influenced by Tony Judt’s description of his own archival research in Provence, where his schedule looked like a daily meditation with different phases.3 In my case, the diet of baguettes, cheese and mineral water was replaced with hummus, falafel and Turkish coffee, and the view of the Mediterranean with the hills of Jerusalem.

By early May, I realized that I could not maintain such self-control. The time spent reading the news was constantly increasing, along with my internal tension. The inconsistency in Ukrainian media coverage was particularly disturbing.

On May 2014, tragedy struck in Odessa. The Trade Unions House, which served as a base for pro-Russian protesters, was burnt down, killing 39 people. However, even local media could not provide a coherent explanation of the tragedy, or even of the mere facts of the events. There was no clarity about how the violence erupted, who set fire to the building, or what the consequences were. The versions were utterly inconsistent; it was a ‘terrorist’ act carried out by Russian agents in order to manipulate public opinion; it was arson committed by Ukrainian nationalist gangs armed with Molotov cocktails bent on destroying the protesters against the ‘Kiev junta’.

A serious impediment to gaining an accurate picture of the situation was the fact that the international media did not have their own correspondents in Ukraine who knew the local languages and peculiarities. Since Soviet times, Moscow has served as the base for international journalists covering the region corresponding roughly to the former Soviet Union and its satellites. Consequently, as they scrambled to cover the developing story, journalists pulled information from second- or third-hand sources, often using Russian mass media reporting, which had an unambiguous and consolidated view of the violence and interpretation of events in Ukraine. The basic narrative it adopted was that the Ukrainian state had collapsed, the country was in a state of complete chaos, ‘nationalist’ and ‘fascist’ gangs were engaged in a violent struggle for power, and that Ukraine was not able to protect its own citizens. The discourse in the Polish, American or German media differed depending on certain internal processes, and culturally specific perceptions of Russia and eastern Europe.

One sunny morning, on the No. 1 tram from Mount Herzl to the Old Town, by Jaffa Street, I noticed an old woman carrying a Russian-language newspaper with a page dedicated to the situation in Ukraine. Thinking it would not be polite to ask to borrow her newspaper, I moved closer, to read it over her shoulder. The article stressed how right-wing radicals had risen to power.

At that moment, I was struck by a very strange feeling. Despite personally experiencing the EuroMaidan revolution in Kyiv, and witnessing almost all the events throughout late 2013 and early 2014, I began to doubt my own experiences. Suddenly, three questions arose: Was I wrong? Were my experiences skewed? Was the media right?

The desire to understand what is happening around us makes us produce a continuous picture of reality, seeking to understand cause and effect. Studying history taught me to perceive events or processes as conditional vectors with points of origin, causes, consequences, and a certain direction of travel. In the case of using these special ‘diminishing’ optics, which allows a comprehensive assessment of the situation, I could in most cases find myself comfortably understanding all this, and developing strategies of response. I could only escape the feeling of turbulence and sense of misunderstanding by using a classic Hegelian rationalization: the owl of Minerva only spreads its wings after dusk, i.e. understanding is only possible in hindsight.

However, in May 2014, this traditional assessment paradigm was broken. Short YouTube videos, allowing viewers to comment instantly, became a phenomenon. The proliferation of smartphones and relatively fast internet now enabled anyone to shoot and post events as they happened. At first glance, this was a huge leap forward. TV channels no longer had to send a van with a satellite dish. There was no need for a reporter armed with a microphone to question participants and witnesses, interpreting the situation on the viewer’s behalf. The mediator disappeared, replaced by a new immediacy where we felt like we were in the centre of events, with only a few seconds delay.

In practice, however, this immediacy was not a blessing. The names of videos or stories included only a place and date, with no additional information or description. The only context available was the name of the YouTube channel. Videos mostly depicted clashes between groups of people. One could only distinguish who was who from the presence of blue-and-yellow insignia or St. George ribbons on their jackets. Such fragmentary, decontextualized images from Ukraine created fragmentation and disturbance of my own experience, which now included doubts about the rationality of the ‘superstructure’, to use a typical Marxian model, and my own assessment of events.

Burdened with these disturbing thoughts, I returned to Ukraine in early June. The end of spring and the beginning of summer were particularly tense. The conflict, which initially looked like a mere struggle of narratives, broke out into a fully-fledged war after local administrative buildings were captured in the Donbas. The belief that returning to Ukraine would allow me to calm down and more soberly assess the situation ‘from inside’ worked only partially. Later the same month, I began to think about volunteering for the army. Continuing to work on my dissertation became unbearable, as did attempts to focus on something other than news from the east.

At the beginning of July, I went to the local military commissariat to ensure my documents were in order and, if necessary, to enlist in the next wave of mobilization. Due to the Ukrainian army’s lack of active personnel and military preparedness, six waves of conscription were conducted between March 2014 and August 2015. I was part of the third wave, at the end of July 2014.

After enlisting, the next step was assignment to a military unit. Military units are, to a degree, similar to sports teams. You are assigned primarily according to health, education and professional skills. The army directs you to a specific military branch that, in theory, matches your strengths and attributes. Infantry, artillery and motorized units are analogous to being deemed more promising at football, basketball or hockey. Subsequently, they choose a specific team for you to play in. These teams are diverse: large or small (brigades or separate battalions), new or old, titled champions or young-and-ambitious.

In choosing assignment to a specific unit, I was guided by two basic principles: location, and history. First, the unit should be based outside Galicia or western Ukraine, my own region. Since mobilization and staffing were often based on a territorial principle, I wanted to encounter people from other regions, to talk and interact, and better understand their identity, beliefs and values. Secondly, it was important to me that the unit had its own history. As a World War Two researcher, I was particularly interested in units formed at that time. After numerous inspections and tests, I landed in the 54th Reconnaissance Battalion based in Novohrad-Volynsky in northern Ukraine, a unit which had been formed near Moscow in 1943 and was attached to the First Ukrainian Front from the beginning of 1944. After fording the Prut River and crossing the Soviet-Romanian border, the battalion was awarded the title ‘Prutsky’ and was subsequently transferred north to participate in the Lublin Operation. After crossing the Polish-German border, the unit received another title: ‘Pomeranian’.

August for me was spent in intensive military training and, in my spare time, study of the history of my new ‘family’. Meanwhile, events in the Donbas were escalating. The battles for Ilovaisk brought the Ukrainian army’s greatest catastrophe to date. The ‘Ilovaisk encirclement,’ the encircling of Ukrainian forces near the city of Donetsk, ended with 366 Ukrainian soldiers killed and 429 wounded. This was the result of direct Russian intervention, including cross-border shelling by artillery, and engagements involving regular Russian Federation army units.

After Ukrainian Independence Day (27 August), our battalion, along with its military equipment, was loaded onto special railway carriages and we were told that our train was going to Izium, Kharkiv Oblast. Our final destination remained secret. On 30 August, the battalion moved in a long column of military vehicles from Izium through the town of Sloviansk, which had been liberated from Girkin’s forces just a month earlier. My initial strong impression was of the landscape – endless hills cut by ravines and small rivers. ‘But where,’ I wondered ‘is the steppe?’ – that endless open space that is supposed to extend beyond the horizon, ending in Inner Mongolia and depicted in the world of literature as the ‘sea of the nomads.’ The landscape in Donetsk Oblast around Debaltseve was very similar to eastern Galicia, with only the slag heaps and headframes reminding you that this was mining country. That feeling of home disappeared within 20 minutes of trench digging, when the tips of our shovels hit solid rock just 30 centimetres below the surface. The ground was so hard that, even using pickaxes, we could only deepen the trench by 50 centimetres by the time dusk fell. My first day on the front line finished with the preparation of a shelter, and an alarming night began with me leaning against the shallow wall of my trench and trying to accustom myself to the cannonade rumbling around me.

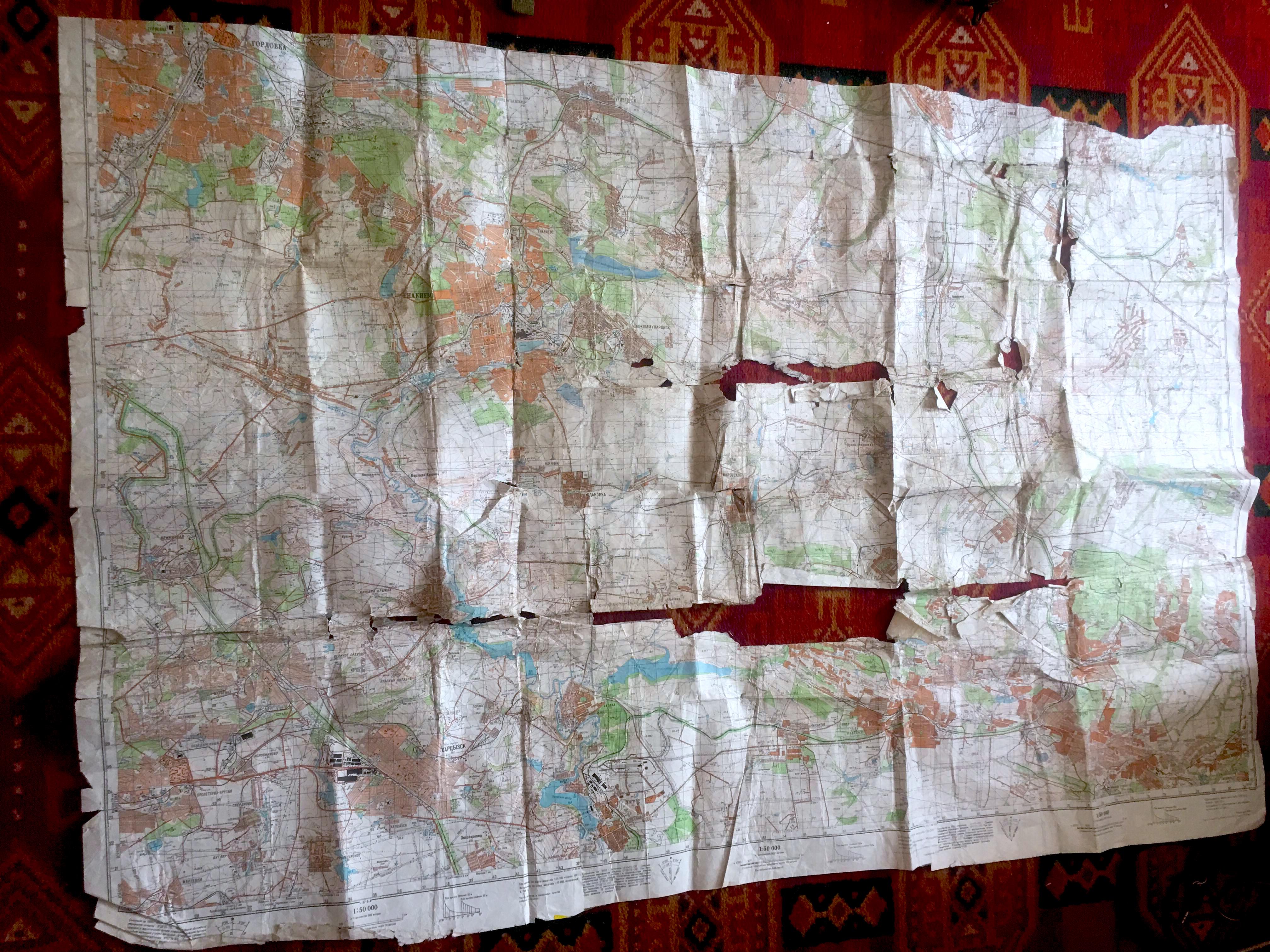

The author’s military-issue map of Debaltseve, Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. Photo: Mykola Balaban

The beginning of October 2014 marked my third month of service in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. We were stationed in a small village northwest of Debaltseve. It was a miraculously calm night, one I hadn’t experienced in all my time at the front. There had not been a single calm night. Each day, at the onset of darkness, sounds of a firefight or distant explosions were heard from different sides.

That night, it was my turn at the command post. My task was to receive information from observation posts, enter it in a special combat situation log, and check the coordinates of possible enemy deployment. Everything was surprisingly calm. Between radio communication transmissions, I managed to read the news on my iPad. For a soldier on the front line, it is very important to get information and communicate with the outside world. Daily practice of war induces a sense of automatism: when you live according to a strict schedule, you perform routine tasks and seldom communicate. These circumstances create a general sense of distance from society, culture and politics – ’detachment from everything’, except one’s orders.

In such cases, any pocket gadgets that have access to the internet, and hence to social networks and news sites, are vital. There is particular sensitivity when any news from the wider world appears. In turn, this opens up another field of struggle: information. Access to a variety of internet sources that supply varying, often contradictory, information produces a certain amount of mood instability, as your feelings swing from despair to exuberance.

Clicking on a link, I came across a June 2014 interview with Vladimir Putin by Jean-Pierre Elkabbach and Gilles Bouleau of Radio Europe 1 and TF1 TV. It had the classic mise en scène of an interview with a world leader: the interviewers politely asked questions, the president responded with characteristic restraint and undisguised irony. Putin confidently dismissed the key question about the involvement of Russian troops in the war in Ukraine: ‘There are no armed forces, no Russian ‘instructors’ in south-eastern Ukraine. And there have never been any.’4

After pausing the video, I went to smoke. Shortly after lighting the cigarette, I saw the night sky erupt in a flare, then a loud roar, of rockets to the north-east, in the direction of Bakhmut. By the sound and trajectory of the four rockets, I realized that they were launched from an Uragan –‘hurricane’ – self-propelled multiple rocket launcher. The Uragan was developed in the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1970s and is manned by four skilled artillery officers. This is a very complex piece of military equipment, requiring a high degree of professionalism and a trained crew, as well as special reloading vehicles. The vehicle itself could not have been captured from Ukrainian Army warehouses (Uragans were never based in either Donetsk or Luhansk Oblasts); nor is it possible to believe that among the ‘self-organized’ militants there were specialists who could effectively calibrate, load and launch such a weapon.

After a minute standing in shock, I dived back into the safety of my bunker where my iPad – with the paused interview with the Russian president – lay on the table. I found myself in a situation where ‘non-existent’ Russian troops launched ‘non-existent’ rockets aimed at possibly ‘non-existent’ victims. My quest to find and understand the context of what was happening in Donbas for a moment became a quest to make sense of this hybrid non-existence.

The experience of that night became for me a confrontation with the face of ‘post-factuality’ and ‘post-truth’ politics of a full-scale war. After this experience, I started to think and read a lot about the concept of truth, its relation to fact and our perception of reality, constantly trying to apply the classical polynomial concept of fact as a truth-bearer, an obtaining state of affairs, or a sui generis type of entity, in which objects exemplify properties or stand in relation to events – in this case, in Ukraine, whether the EuroMaidan revolution, the annexation of Crimea, or the war in Donbas.

Key thinkers of the last sixty years have sought to eliminate the possibility of a return to the totalitarianism, mass violence and militant ideologies that in the early twentieth century poisoned even the most modern and successful societies. They were attracted by the idea of deconstructing the concept of fact, isolating the truth-bearer to a relative sui generis. Such views were relatively successful in the struggle against the Nazi or Soviet totalitarian regimes, which were built on the metanarratives of a single ideology or a single truth and promised, through irreversible commitment, to put both society and individuals on the ‘right side of history’. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, in the brief period of the ‘End of History’, this anti-totalitarian critique was reconfigured by the ideology that it was designed to combat. In my opinion, this phenomenon occurs at the crossroads of two streams – on the one hand, a demand from the reactionary elites of collapsed totalitarian states, who fear liberalization, democratization and globalization in their own societies (a state of affairs in which a corrupted few cannot maintain effective control), and on the other, supply from Sonderweg intellectuals who are looking for a new language to rebrand their anti-liberal beliefs. Taken up by groups as diverse as religious-fundamentalist populists and militant Eurasianists, one sees the pure form of this reconfiguration in a 2016 interview given by Russian thinker and ideologue Aleksandr Dugin to the BBC on the idea of a special ‘Russian truth’.5

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt defines totalitarianism as a situation in which ‘the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true.’6 Sixty years later, Peter Pomerantsev revived the formulation for the title of his book Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible,7 which described contemporary Russian society. The blurring and relativization of fact has opened the door for the new phenomenon of ‘post-truth politics’. The events of the last three years – the wars in Syria and eastern Ukraine, the annexation of Crimea, Brexit, and the 2016 US presidential campaign – represent the triumph of post-factuality and post-truth, and demonstrate its dangers.

However, in our analysis of the above-mentioned events, and their processes and technologies, we risk falling for the explanation that they are limited to social networks, ‘bot farms’, manipulation of information, and the interference of foreign intelligence services in electoral processes. But the events in Ukraine – some of which I experienced, and have described here – and Syria show that reality can quickly move from manipulated messages – such as ‘the EuroMaidan is an anti-government putsch by right-wing radicals’ – to fully-fledged war using the entire spectrum of lethal weapons, where people – still now, years on – die every day. Truth, according to the architects of post-truth, is relative. But, as millions of people experience daily in Ukraine and Syria, there is nothing relative about death.

Михаил Булгаков. Дни Турбиных., Concorde, Paris., 1927. p. 24.

Translation by Michael Glenny, 1971 McGraw-Hill edition.

See: Tony Judt (with Timothy Snyder), Thinking the Twentieth Century (2012), chapter 5.

See: ‘Vladimir Putin’s interview with Radio Europe 1 and TF1 TV channel’, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/45832 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MrFqCF0dbgM&t=733s (11:16 to 11.25).

See: ‘Aleksandr Dugin: 'We have our special Russian truth' - BBC Newsnight’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GGunRKWtWBs&t=13s

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951).

Peter Pomerantsev, Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia (2014).

Published 25 April 2018

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Mykola Balaban / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

As capital consolidates, culture recedes, funding vanishes, access narrows. The question persists: why fund culture at all? Cultural managers from Austria, Hungary and Serbia discuss.

Russian drones entering Polish airspace, militarily seen as intensified provocation rather than open warfare, have nevertheless provoked costly responses – both from NATO’s air defence systems and civilian reactions to disinformation. A war correspondent’s view of what can be done technologically – for greater military efficiency and improved civil defence.